Alienation, as Mr. Harold Rosenberg has lately reminded us, is becoming an overworked and threadbare concept. Nevertheless, it’s hard not to use it when talking about Doris Lessing, two of whose early novels have now appeared in a one-volume edition entitled Children of Violence. In all her writing Mrs. Lessing has returned time and again to the study of lost and alienated beings in some of the major proletariats of the modern world, notably the African natives and poor whites of Rhodesia, where she grew up or the emancipated woman of twentieth-century urban society, educated, articulate, and yet as much a prey to sexual exploitation as her unliberated counterparts in less enlightened times. A typical Doris Lessing situation will concern a white couple on a crumbling farm in a remote part of the veld, declining into the neurosis born of prolonged failure and frustration, observed closely but silently by their native servants, with their progress to inevitable disaster perhaps recorded by a female child from a neighboring farm, who has all the perception of Henry James’s Maisie and rather more understanding. Or, in Mrs. Lessing’s more recent fiction, we might, for instance, be invited to observe a brief, abrasive affair between a London professional woman, once married but now divorced or separated from her husband (with a child possibly in the background), and a weak, amiable, vaguely self-seeking intellectual, whose own marriage has long since ceased to mean anything, and who is unworthy of her.

Doris Lessing did not go to England until she was thirty, and her accumulated African experiences were crystallized in her first two books, both of remarkable imaginative strength and authority: a novel, The Grass Is Singing (1950), and a collection of stories, This Was the Old Chief’s Country (1952). In these books Mrs. Lessing made a pained but unflinching examination of the manifold ways in which human beings are forced apart: the primary alienating force was, of course, the moral enormity of the color bar, but she was also concerned with the divisions in the white community between the British and the Afrikaaners; and with the cruel though invisible barriers between husband and wife. And also in the background, underlining by its indifference the puny human tragedies, was the parched and inhospitable veld, stretching for miles under a vacant, blazing sky. Few modern writers have established so immediately their own unmistakable world.

The dominant influence on Mrs. Lessing’s early fiction, particularly her stories, was certainly D. H. Lawrence; she frequently catches Lawrence’s precise tone of urgent casualness—“The Farquars had been childless for years when little Teddy was born,” the opening of a story called “No Witchcraft for Sale”—and she echoes, too, his awkward, rather baffled comments on his own characters: “Perhaps he really did feel he ought to marry. He knew it was suspected that this new phase, of entertaining and being entertained, was with a view to finding himself a girl.” But Mrs. Lessing got more from Lawrence than a manner or a tone of voice. Like Lawrence, she has a didactic strain, a desire to make the implications of her fiction plain to the reader, and she follows Lawrence into sometimes schematizing her stories, manipulating the symbolism with too heavy a hand. The Grass Is Singing has elements of a Central African Lady Chatterley’s Lover: the neglected, neurasthenic white wife, Mary Turner, turns to her black house-boy Moses with feelings that change in time from intimate hatred to an undisguised sexual fascination: though the end, in Doris Lessing’s novel, isn’t regeneration but squalid tragedy. The situation is, undoubtedly, credible; but it is still overdrawn. In particular, the character of Moses is worrying; he may have been taken from life, but he also recalls those black inscrutable figures with dark gods in their vital centers who are such a tiresome literary cliché. Again, in a story like “The Second Hut” there is a sharp allegorical confrontation between the mild, kindhearted Englishman, Major Carruthers, an unsuccessful gentleman farmer, and Van Heerden, the young Afrikaaner whom he engages as an assistant; Van Heerden is crude, brutal, even animal-like, with a huge family and an everpregnant wife; despite his disagreeable qualities it is evident that he is firmly “on the side of life,” whereas the unfortunate Carruthers, burdened with an invalid wife, is not. After certain crucial encounters with Van Heerden, Carruthers retires defeated: “‘I’ve written for a job at Home,’ he said simply, laying his hand on her thin dry wrist, and feeling the slow pulse beat up suddenly against his palm.”

In the later stories, which are written with greater sophistication and technical accomplishment, though not with greater feeling, Mrs. Lessing’s inclinations towards symbolism sometimes emerge in highly complicated forms. One notable example is the novella, “The Eye of God in Paradise,” published in 1957 in The Habit of Loving, in which two British tourists, an established though unmarried couple nearing middle-age, both doctors of medicine with impeccably liberal views, take a winter-sports holiday in Germany in 1951, their first post-war visit. In a series of bold images, Doris Lessing sets off the traditional “charming” Germany, symbolized by the Alpine resort and its folk-singers, against the Germany of Hitler, still very evident in the form of unrepentant ex-Nazis. The story culminates with a professional call that the doctors pay on Dr. Kroll, a bizarre figure who is the respected head of a mental hospital; he is exquisitely cultivated but plainly schizoid (indeed, it is said that he spends part of each year as a voluntary patient in his own hospital). Mrs. Lessing sees Kroll as an embodiment of the two faces of Germany, and she elaborates the dichotomy with a wealth of conscious symbolism. The elaboration is, it must be confessed, too great; but the novella makes a powerful impact. It gives a vivid, if non-rational, expression to certain British feelings about Germany which are still a factor in contemporary politics (and which are so puzzling in other quarters of the globe).

Advertisement

Much of Doris Lessing’s literary production has been in the medium of the short story, a form she has mastered with extraordinary skill and ease. It lends itself to her particular purposes, since as Frank O’Connor has suggested, the short story is very suitable for the treatment of submerged or alienated beings, the victims rather than the victors of the world; and these are Mrs. Lessing’s constant subjects. But her increasing mastery of the form has been won at some cost: the consciousness that one can turn out an effective story about practically any incident, no matter how slight, can lead to a dominance of manner over matter. Many of the pieces in Mrs. Lessing’s last collection, A Man and Two Women (1963), are technically brilliant but noticeably thin: if the best of her early stories could stand comparison with Lawrence, or the Joyce of Dubliners, too many of the later ones, in which the smooth precision of the fictional mechanism is linked with a harshly cynical response to life, recall Somerset Maugham.

There is one important respect in which Doris Lessing differs from other distinguished female practitioners of the short story, such as Katherine Mansfield, who are content to rely on the unsupported notations of the sensibility. Mrs. Lessing is unashamedly an intellectual, concerned not only with ideas but with ideology—a concern which took her for a few uneasy years into the Communist Party—and is keenly interested in the way contemporary society actually works. One of her best books is In Pursuit of the English (1960), an account of a year she spent in a seedy London boarding house soon after her arrival in England. This book is funny and harrowing in a late-Dickensian way: the landlords, Flo and Dan, live cheerful, Rabelaisian lives, serving and eating enormous meals; but at the same time they neglect their little girl so shamefully that the public authorities threaten to take her from them. The house is pervaded by an air of blowzy good spirits, though this does not stop one of the female boarders from aborting herself with an enema; she is very ill afterwards, and the foetus, as Flo blandly reports, is thrown down the lavatory. By the time she wrote In Pursuit of the English Mrs. Lessing had evidently come to feel that experience was too complicated to be divided into the easy categories of pro- or anti-life.

Her larger interests could not be easily contained in the restrictive medium of the short story, and it was inevitable that Doris Lessing should turn to the novel, even though it is not entirely certain that she is a novelist by natural bent (The Grass Is Singing had the simple outlines of a fable, and was basically an enlarged short story). In 1952 she embarked on a series of novels about the physical and intellectual adventures of a heroine of our times called Martha Quest: the first two of these Martha Quest (1952) and A Proper Marriage (1954) are now reprinted under the title of Children of Violence, the name of the as yet unfinished sequence. Martha grows up on a remote Rhodesian farm, in the familiar milieu of Mrs. Lessing’s early fiction: there are some beautiful passages about her adolescence which have the poetic quality that Mrs. Lessing’s imagination seems to produce only when she draws on her African memories. Martha, a wayward but sharply intelligent child, leaves the farm and takes a job as a secretary in the city. Thereafter the novel becomes a Bildungsroman with a self-emancipating female hero: a combination of The Way of All Flesh and The Doll’s House. Martha takes up with the local fast set, learns to drink and do without sleep; she clinically loses her virginity to a Jewish violinist, then enters into a futile and apparently quite unmotivated marriage with a young civil servant. They have a child, the Second World War is declared; Martha’s husband goes off as a soldier, and she becomes actively involved in left-wing politics; he returns, invalided out with a stomach ulcer. Martha finds him intolerable and leaves him: at this point A Proper Marriage ends.

Advertisement

Children of Violence is unsatisfactory for a number of reasons. After the early scenes of Martha’s adolescense we cease to learn anything more about her. She becomes, instead, the vehicle for a series of observations of the Rhodesian scene; increasingly we see her as the mere focus of a variety of attributes, ranging from mild girlish debauchery at the local Sports Club, to the dissatisfactions of a loveless marriage, and the growth of left-wing idealism. Little sense remains of Martha as a unified developing personality, and her husband is an unrealized cypher. The best sections are documentary: Mrs. Lessing’s account of middle-class life in what was presumably Salisbury in the late Thirties and early Forties is horrifying; she makes it seem the ultimate cultural slum of White Civilization. And Martha’s painstaking observation of her pregnancy is a good deal more exact than one customarily finds in fictional accounts of similar situations.

It would be as idle to deny that Children of Violence is substantially autobiographical as it would be impertinent to try to relate too closely Martha’s life with her creator’s. But the book’s autobiographical nature may well account for its flaws as a novel; a natural refusal to explore too fully certain painful events might well account, for instance, for the shadowy treatment of Martha’s marriage.

There can be no doubt, either, that Mrs. Lessing’s most recent and ambitious novel, The Golden Notebook (1962), is also, among many other things, strongly autobiographical. Indeed, one of the book’s principal concerrs is to raise, insistently and repeatedly, the whole question of the relation between “life” and “art,” particularly the art we are accustomed to find in novels. The Golden Notebook is a work of determined modernity, both in matter and form. If Martha Quest and A Proper Marriage were about the struggles of a young woman for emancipation, then The Golden Notebook shows us the harder if less dramatic struggles of an older woman who has long since achieved it. Anna Wulf, the book’s heroine, is, in essentials, an older version of Martha. Though born in London, she too lived in Rhodesia during the war years, where she was involved in left-wing politics and contracted a brief unhappy marriage. She returns to England after the war, and in 1957, when The Golden Notebook opens, she has made a name as the author of a single bestselling novel, Frontiers of War, has been a Communist for a few years, and has undergone psychoanalysis. She has never married again, though for five years she was the lover of a Central European refugee, and has had many minor affairs. On the face of it, Anna Wulf has achieved a state of personal freedom that the New Woman of Ibsen and Shaw could scarcely have dreamt of; she is as free as any man in all the major spheres of life, professional, intellectual, sexual. Only her deeper emotions remain unliberated; she is conscious of a surviving need for dependence, and the clash between her desire to control her own destiny and her passionate love for a young American writer takes her to the brink of insanity, and provides a major theme of the novel.

Such figures, and such situations, are by now common enough in western society to be significant, though their dilemmas have not, so far, received very searching fictional treatment. Mrs. Lessing links her concern for this new and demanding topic with a conviction that the traditional novel form is inadequate to express it. Thus, formally, The Golden Notebook is a brave attempt to break through the impasse in which the novel has found itself since the publication of Ulysses. In one sense it looks back to Gide’s Les Faux-Monnayeurs as a novel that deliberately incorporates and exposes its own processes of composition. Only a small part of The Golden Notebook is taken up with a conventional narrative of Anna’s life: the greater part of it consists of long extracts from her four notebooks; the black, in which she recalls her Rhodesian experiences, the source material for Frontiers of War; the red, in which she describes her somewhat sticky dealings with the British Communist Party; the yellow, in which she is writing another novel; and the blue, which contains a personal diary of her day-to-day life. Yet though it may recall Gide, The Golden Notebook is part of a highly contemporary cultural movement which lays a large stress on process, ranging from the action-painter who asserts that his work is an event not an object, to the kind of literary scholarship that is so beguiled by source material, early drafts, notebook outlines, etc., that the finished work becomes much less an object of study than the processes which led up to it. The Golden Notebook is a work of great brilliance, dominated throughout by Mrs. Lessing’s hard, analytical intelligence, with many passages of verbal virtuosity, especially of a parodistic kind; like the reviews of Frontiers of War from the English-language Soviet press, or the spoof journal of a young American wandering through Europe, or, above all, the piece headed “The Romantic Tough School of Writing,” which begins: “The fellows were out Saturday-nighting true-hearted, the wild-hearted Saturday-night gang of true friends, Buddy, Dave and Mike. Snowing. Snow-cold. The cold of cities in the daddy of cities. New York.”

But these are no more than welcome jeux d’esprit on the surface of a work which is fundamentally written against, rather than within the form of the novel. Mrs. Lessing, or Anna Wulf speaking for her, makes this clear: in one of her notebook entries, Anna tells her psychoanalyst that she no longer believes in art; and elsewhere she rebels against her inclination to turn an incident she has just witnessed into a story: “It struck me that my doing this—turning everything into fiction—must be an evasion…Why do I never write down, simply, what happens?” There may be good, even overwhelming reasons for doing just that; but to follow such an impulse systematically would result in the overthrow of fiction as a literary form.

Mrs. Lessing’s dilemma may partly reflect an aspect of our culture—as in the current neo-dadaist assumption that the raw flux of life is inherently superior to an art of selection and synthesis—but basically it must stem from the kind of crisis that sometimes leads novelists, at a certain stage of their careers, to turn inward and write about the creative process, or its difficulties: one thinks of James’s stories about novelists, or such recent examples as Evelyn Waugh’s The Ordeal of Gilbert Pinfold or Graham Greene’s A Burnt-Out Case. Certainly few novels can have been so painfully explicit about the business of being a novelist as The Golden Notebook, and there is an uncomfortable Chinese-box effect in discovering Doris Lessing writing a novel about Anna Wulf who is writing, in the yellow notebook, a novel about a girl called Ella who is writing a novel about a young man who commits suicide. One is faced here with what Matthew Arnold long ago diagnosed as “the dialogue of the mind with itself”; one respects Mrs. Lessing’s honesty and pertinacity in pursuing her preoccupations so far, while regretting that she has apparently exhausted the simple but fruitful tensions of her African material. So admirable a talent deserves something better than to be confined in a hall of mirrors.

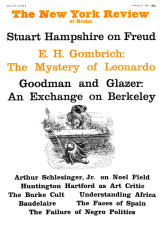

This Issue

February 11, 1965