The writing of poetry today is an immense free play. It somewhat resembles the modern household, each member going about his or her business, meeting fortuitously, the contact producing sometimes a flare-up, sometimes a guilty rapport, or simply indifference. That pleasant political dichotomy of just a few years past, the Academics vs. the Beats, no longer holds. Splitting the ticket is very much the thing. As for definitions, is poetry a “criticism of life,” or a “symbolic landscape,” or a “barbaric yawp”? No one knows, and certainly, despite the occasional call-to-arms, hardly anyone cares. The poets I discuss come from different generations, they reflect different ends and means; taken together they offer, I think, a good cross-section of disparate modes. Yet the scraggiest of them drag in some bit of intellectual esoterica, the most genteel now and then use slang. Not one works in what could be called a pure tradition, a term which, in any case, has become problematic. As will be seen, each review is self-contained and, with one exception, I have made no attempt at “bridging.”

Like a stripped rabbit, the populist spirit of the Thirties is turned inside out in Edward Dorn’s bleak, lean, belligerent poems, most of them a “living speech” meditations on the American Southwest, over which the shadow of Disneyland squats.

Let us not mention Ford workers,

or generations of workers father & son

or that goddamn shit about divid- ing

up the land, They

who divide do so in order to

keep keep keep: They simply get what they want—an economy is never more intricate than that…

Flabby, pallidly corrupt, stupefied with goods (even “cowboys live/in ranch style houses”) meanly wistful or repressed

They say “Well, Stevenson speaks well, is at home

with ideas (yi)…why can’t it be

why can’t we have a good man

what the hell is wrong, son of a bitch

I’d like to tear somebody’s throat out

Geezchrist, but he does speak elo- quently

—so the workers have been betrayed, and by themselves. Social concern (trade unionism, democratic renewal—all those boring New Deal touchstones lie about collecting dust, grass, flies, the inevitable bulldozer bearing down none too soon.

Full of ambivalent protestations, full of caring and not caring, of a kind of cheap knockabout exhaustion—one’s travels prove too fierce, complex, circular:

What I already knew: not a damn thing

ever changes: the cogs that turn this machine are set

a thousand miles on plumb, be- neath the range of the Hima- alayas

Dorn’s poems, nevertheless, gather strength, and within limits, a remarkable authenticity, in various ways: through a deadpan romanticization of the frontier past (Meriwether Lewis, Tecumseh, even Thoreau), the use of mock-Cantos effects (especially in the book’s roomy, central, attitudinizing poem, “The Land Below”), and in the fine, incidental spurts of regional detail, e.g., “The snow lays against the slope/as skin clings to a baby giraffe…” But above all—and it holds too, I think, for Dorn’s much more depersonalized short stories—through the man himself, his grimness, his hard-nosed subjectivity. Behind the implied moral rebuke here to the way things are, behind an elegiac remembrance of a post-depression mining town (“Its houses stand unused…every window has been abused with the rocks of departing children”), or the tender desolation of “On the Debt My Mother Owed to Sears Roebuck,” stands not the figure of Pete Seeger, or a guitar-strumming civil rightist, but that of the contracting-out stud, Brando in blue jeans. (In The Wild One, the despairing square asks, “What are you rebelling against?” the motorcyclist responds, “What have you got?”) If it is true that “bad faith” is America’s trouble, Dorn is very American.

Something more than just American, actually international, is the cult of “self-expression.” Destinations, a case in point, comes both as a recording and as a companion-piece volume; it illustrates the rite de passage of the “open readings” or of the experimental through the cultural underground. Four poets are included: two unknown (Norman Pritchard and Jerome Badanes), one with clippings (Paul Blackburn), and one “comer” (Calvin Hernton). In Destinations it seems they’ve all gathered together for a rendezvous with death. Aside from “Bryant Park” (a tight, long-lined apostrophe to metropolitan loneliness and a moment of magical release), Blackburn, the talented member of the anti-Establishment Establishment, is goofing-off. Perhaps he was hijacked. Pritchard, I’d say, has a vocational delusion large enough to fill in the Grand Canyon.

Men alcoved in agonies sprawl their lives outwardly upon an inward world as if bottled in a dream preferred. Often dreams (however holy watered)…

A Tennessee Williams parody? Badanes wanders through his free-floating squalor like an updated, hallucinated Vachel Lindsay; Corso comes out of one corner of his mouth:

Advertisement

You! Mister Misery!

What buds break in your brain?

You! Drowsing Agent!

I see your one eye peeking.

And you you there you you you you you you…

and Ginsberg the other:

I whistle across water at Brooklyn Bridge.

Birds burst from my lips toward Brooklyn Bridge.

The setting sun hums on Brooklyn Bridge…

Hernton is the author of a heralded underground work, The Coming of Chronos to the House of Nightsong, which I am sorry to say I have not read. Here his “The Passengers”—as Riesman-type rotating robots—has the fascination of a slow-motion newsreel; the solemn mumbling of “Burnt Sunday,” on the other hand, with its idiomatic shifts from Eliot to Thomas to Whitman, is awful. While the work of Dorn and Blackburn, Corso and Ginsberg, for instance, contains the early, vital phase of “projective verse” (a prosodic technique based not on traditional metrics, but rather on a breath-by-breath movement, a “spontaneous” rhythm), that of Pritchard, Badanes, and Hernton represents (as was perhaps inevitable) its later, mushier, mongrelized state. Tremulously abject, or manic, sweetly abusive, or putatively prophetic, these three young men engage in poetry as if in a world of self-energizing permissiveness, a long night’s frustrations leading to amorphous fancy. You might call it Pot Art, only with the reverse effect. When one closes Destinations, as when one closes so many of the newer underground broadsheets, then the clouds lift.

Of course, criticism is de trop: “self-expression” means, among other things, self-exemption, self-congratulation. Or if it is to be, it must be criticism from the inside, in Sartre’s sense that one must work with the Communist Party, not against it, in order to earn the right to criticize it. Or from another realm, Jonas Mekas decrying technical fuddy-duddies: “You criticize our work from a purist, formalistic and classicist point of view. But we say to you: What’s the use of cinema if man’s soul goes rotten?” Some have found considerable value in these sentiments; to me, they all sound like fancy rationalizations, or in the plain man’s tongue, cop-outs. Anyway, let editor Wilmer Lucas (“Above all, I did not collect these poems…in many respects they collected me”) have the floor:

Men live but Saints perform!…These are the “DESTINATIONS” of four young men as sages in our times. Each with his own sound wisdom…and each with his own appointment to GOD…and HIMSELF…America is a whirlpool fantasy of a poly-cultural complex forbearance…always in its perpetual state of flux…These Poems are our times…The Poet has been an astronaut and its aqua autic counterpart before there was such to deal with. These Poems are his realizations and yours, and mine, for evermore, individually.

Top that, Eastern Airlines!

You’re eating, you knock over a half-filled glass, you’re startled to see so much water or wine spreading, and in so many directions. Jean Garrigue’s lengthy lyrics are like that: they all have a fluid busyness, a little discomforting, certainly unexpected, since the initial impulse seemed misty, the rhythms almost solemnly tentative. So you reread, you discern a musical structure, in a way, an attempt at exposition, development, recapitulation. Then the language intrudes: “niddering,” “larky,” “champing,” “lopped”—irregular, delighting adjectives; they should work, but they don’t, quite. Invariably at the center of the poems in Country Without Maps is a bright nervous blur, vaguely fitful, like a winter sun. The ladies are here: Millay, Dickinson, Rossetti.

Get me the purity of first sight!

Or strength to bear the truth of after light!

But also Hart Crane:

The truth connects us but the more is love—

Without that top to wind, no way to go

Celebrants all, of the ladder up the mow

And children calling—smoke forms of the snow!

Even Stanley Kunitz, when he gets on his high horse:

Although they rage to go

Into the soft cold madness of the snow

Or anywhere! beyond the blooded brags!

To smash, if nothing else, the vase from China

Inspect the high-born motives of some Uncle,

Know Mother for what she did not want to do

And Death the testy teacher of them all…

Miss Garrigue’s sensibility has a tattered “virginal” quality, a sort of aging ecstasy. Densely packed, her meanings are at once both remote and close-up; the imagery gaudy as a Venetian clock, or beautifully specific:

…leaning lilies much too tall

To sustain their flaring crowns,

Veronica, vervain, bent over by the rain,

And Queen Anne’s lace upon its gawky stem.

Born in 1914, part of poetry’s early post-war generation, Miss Garrigue is one of those odd, problem-ridden free spirit; she collects the knickknacks of experience, rather than the soiled, palpable relationship to others, to the world. Technically and imaginatively, a great deal of striving goes on, but it always seems in excess of what one finds. Her cat, her “pampered beast,” “Cast down in the dirt/Of death’s filthy sport”; her “caged birds” and she “their jailor” imprisoned in dreary finitude; her garden, dreams, fevers; her circus animals, survivors of Eden (“They do not see themselves as charming or as good,/Indeed, they do not know their worth/And if they did, how could we care as much?”); her Baudelairean ships, travels, movement—her life. Miss Garrigue is always in transit, ardently, mysteriously journeying somewhere, the hours ticking. Time, or the fear of it, goes through peculiar metamorphoses: the unwelcome guest, the demon lover, the yearning aesthete, pinned down on paper like a butterfly, or simply Time, “that phantasmal space,” “the lull in the mountains,” a metaphysical snare. And in the background intimations of romance, a barely perceptible bird cry of lust, some small “blues.”

Advertisement

Not quite a poet of the senses and not quite one of the mind, enveloped in a fierce reverie, a little like a religion one is faithful to but not at all sure what the commandments mean, Miss Garrigue strikes me, in many ways, both good and bad, as a “private enthusiasm.” I can well understand those hooked on such profligate richness, so many “dazzling” perceptions. I can also appreciate a different view. Parts of “Cortege,” “Amsterdam,” “Remember,” “Pays Perdu,” among others, are unquestionably admirable, though on the whole I do not find Country Without Maps the equal of the handful of works by her I’ve come across in anthologies, nor of her other collections, The Monument Rose and A Water Walk by Villa D’Este.

In the mid-Fifties, when Henry Luce absolved certain de-radicalized intellectuals and christened them Men of Affirmation, academic poetry shifted gears. A popular example of such a turnabout was Donald Hall’s first volume: awkwardness à la Hardy, elegance à la Auden, a New England earnestness and Harvard wit, l’éducation sentimentale the theme, and no moaning at all.

I took the stair again, and said good-by

To childhood and return,

Nostalgia for illusion, and the lie

Of isolation. May I earn

An honest eye.

In his next book, three years later, the suburbs darkened; snapshots of people and places expressed an uneasy mockery, or a queasy wisdom, somewhat like Larkin’s. With A Roof of Tiger Lilies, style and sensibility drastically contract. The impression is one of entering a monk’s cell, where the few objects on view seem to have come from some other place, from enormously cluttered other rooms. A description like that, of course, characterizes the “hermetic” poem, a European product. Yet if Hall is quite recognizably American and still uses a mostly syllabic structure or blank verse, the elusive transitions, the seemingly uneventful actions, suggest a foreign aura, as do the dehydrated wonder and suffering, and the solace, what there is of it, that exists primarily between the lines.

Hall’s culture heroes, judging by his poems, are the artists Munch and Henry Moore, and Henry James, whose time-travel fantasy, A Sense of the Past (which inspired the play Berkeley Square), is interestingly treated in “The Beau of the Dead.” But though no reference is made to it, it is another James work, The Beast in the Jungle—that tale of unused energies revenging themselves—which proves to be the real crux of the matter. Hall addresses himself “to the grand questions,” so states the dust jacket; I think, on the contrary, he evades them. What is exhibited in these poems is not so much the inability to feel, but the diffident, dispassionate man’s inaccessibility to experience, to let loose the demons. Guilt, waste, thanatophobia, a mood of suspended desperation hovers everywhere. Indeed at thirty-seven, Hall appears to be taking on the burden of approaching middle age as if he were Atlas getting ready to carry the world. Also a feeling of isolation is here, especially, I gather, from History: the recent wars which made no sense, the rumors of wars which never end. In his beautifully controlled nature studies, in the eerie impressionistic remembrance of his father, or some other aspect of his past, and in the pictures of estranged husbands and wives or lovers, some outlet is sought, some transfiguring “leap” proposed. Yet, to me, anyway, what comes across is merely a nostalgic drift, oblique emotional gestures. Psychologically, these poems do not fulfill themselves; aesthetically, however, I consider them Hall’s most impressive achievement. Special, sparse, magnetic, the best of them haunt the mind, moving on a dark tide, like an ice floe down river.

It is difficult to predict what Hall will do next. Each of his volumes has grown successively more negative in tone, though always ending on a note of uplift: the glamor of human endurance in the first two, a sort of neomysticism here. “Birth is the fear of death,” he says in the opening poem; “I am ready for the mystery,” he says in the last. Among his contemporaries, his affinities are with James Wright, James Dickey, Louis Simpson, and, especially, Robert Bly, the least mentioned but probably the most talented of the group.

Here is Hall’s “At Thirty-Five,” in part:

But if the world is a dream

The puffed stomach of Juan is a dream

and the rich in Connecticut are dreaming.There are poor bachelors

who live in shacks made of oilcans

and broken doors, who stitch their shirts

until the cloth disappears under stitches,

who collect nails in tin cans.The wind is exhausted.

Here’s Bly:

The rich man in his red hat

Cannot hear

The weeping in the pueblos of the lily,

Or the dark tears in the shacks of the corn.

Each day the sea of light rises

I hear the sad rustle of the darkened armies,

Where each man weeps, and the plaintive

Orisons of the stones.

The stones bow as the saddened armies pass.

Faulkner spoke of the novelist as a “failed poet.” In a provocative sense, not necessarily nasty, the reverse may be said of Mona Van Duyn. Blending the light (Phyllis McGinley, Elizabeth Bishop, the later Auden) with the dark (Modern Literature, the “complex fate”), sprinkling summery particulars and sour after-thoughts, funny yet compassionate, working with slant rhymes, a sestina, couplets (end-stopped and enjambment), her poems, so rattlingly well assured, are less poems (they can all be easily paraphrased, for one thing), than a series of sketches, essayish anecdotes of experience, the Thorny Way as a Liberal Education, or vice-versa. The epigraphs from Santayana, a biologist, the St. Louis Post-Dispatch; the portraits of a doctor, a paratrooper, the next-door bore, or a Texas aunt (the evangelical nut sending news of Armageddon); the notes “Toward a Definition of Marriage”; the scene outside one’s window, the thoughts while in one’s kitchen (“I’ll never climb Eiffels/see Noh plays, big game, leprous beggars, implausible/rites, all in one lifetime. My friends think it’s awful./It leads to overcompensation”); or the confessional in one’s head (the crack-up, the hospital, the Frommian beatitudes: “And now, in the middle of life, I’d like to learn how to forgive/the heart’s grandpa, mother and kid, the hard ways we have to love”)—all very contemporary subject matter, a day-to-day, mildly at-loose-ends world. For politics: a wry anti-utopianism; for philosophy: Camus’s Mediterranean mesure, only domesticated, flat-chested hedonism, unillusioned, responsible.

I may seem grudging but even in Miss Van Duyn’s rigorous, rather splendid title-poem about the death of bees that had been nesting within the walls of her house, which is really a parable on the necessity of civilization to kill the instinctive life—even there, something’s hokey. A scientist-friend comes over. “He wants an enzyme in the flight-wing muscle.” He fiddles with the bees. Miss Van Duyn draws back. “I hate the self-examined,” she exclaims, “who’ve killed the self.” Deft touch—but I don’t believe it. In her poems of such knowing equanimity, Miss Van Duyn crosses all her t’s, dots all her i’s; there’s no intensity, no confrontation here, only the idea of such things. The idea is always around, like road signs. In the end, I’m afraid, I respond as I do to the dénouement of a finely wrought, untroubling piece of fiction. “Her whole Life is an Epigram, smart smooth & neatly pen’d/Platted quite neat to catch applause with a sliding noose at the end.” Thus Blake, on another occasion.

Richard Henchey teaches English at Williston Academy in Massachusetts. His privately printed poems suggest he has been to school with Stephen Crane, and been left back. Long on brevity but short on wit, Henchey is an earnest soul: he believes in what he’s about. Here’s “To Jean-Paul Sartre”:

If I choose not to choose

Have I made a choice

Or am I salivating

To the maddening toll

Of an irrefutable bell?

No doubt to be answered by the Master with a two-volume note. In “Essay on Courage,” Hamlet is sent up the river to Reading Gaol:

The coward kills

A thousand thoughts.

The brave man

Lets them live.

Henchey is brave. Alas.

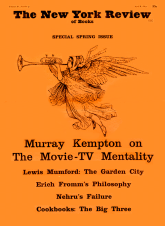

This Issue

April 8, 1965