When is a Roman Catholic not a Roman Catholic? Or, to put it more bluntly, when is apostasy not apostasy? Each of these books poses the question in a different way.

Early in December, 1966, subscribers to The Clergy Review were surprised to read a sentence written by its editor, Father Charles Davis, a leading Catholic theologian, then Professor of Dogmatic Theology at Heythrop College. Referring to the contraception controversy, he remarked that it seemed to him “the Church was in danger of losing its soul to save its face.” Shortly afterward an audience far larger than The Clergy Review had ever succeeded in attracting learned that Mr. Davis, as we must now call him, had left the Roman Catholic Church and was about to get married.

Mr. Davis summoned a press conference and explained his position on television. He contributed an article to a Sunday newspaper. That position he now states more temperately, and of course at greater length, in A Question of Conscience. In brief, his thesis is this: He left the Church not for the love of a woman but because he had ceased to believe in Catholicism. He had ceased to believe in it on two grounds. First, some of the dogmas it teaches are intellectually untenable and unsupported by biblical or historical evidence. Second, the institutions of the Church are corrupt, its yoke an unbearable oppression; as a socially structured body it is an obstacle to Christian faith, a zone of untruth, no longer credible as the embodiment of the faith. It cannot reform and remain itself. Therefore it must be rejected and opposed. Mr. Davis is now Visiting Professor of Religious Studies at the University of Alberta.

“In the reaction to the news of my defection,” he writes, “there was evident a strong element of surprise.” Not however in all quarters. For some time Mr. Davis had been radically contradicting himself in print. It was not intentional equivocation; rather, he had reached the point where he really did not know what he believed.

Self-blinded before and left in the lurch now, some of his admirers proceeded to make a fool of him. They seriously compared his departure to the defection of Newman from Anglicanism. Some even went so far as to call this total rejection of their faith a martyrdom. At one moment it began to look as if a contingent from the Newman Society was about to venture forth over the Alps in winter to beg the Holy Father to grant Mr. Davis that much coveted medal proecclesia et pontifice.

At the opposite extreme there were those who suggested that the Gospel light shone more brightly from the eyes of his fiancée than it did from the pages of Holy Writ. There can be no doubt that his marriage did much to destroy the credibility of his protest. This was inevitable, but unjust. I am quite sure that Mr. Davis is speaking the truth when he tells us he did not reject Catholicism because of his wife but nevertheless without her affection and support he never could have summoned up enough strength to make the break. So we are left with a puzzle. How did it come about that a man of his ability had to wait till middle age before discovering the strength of what are, after all, familiar arguments against Roman Catholicism?

I THINK the answer is that from the first Mr. Davis was the victim of a very bad system, though not quite in the way he suggests in his book. He went, as he says, to a junior seminary at the age of fifteen, then on to further studies at Rome, finally returning to his seminary to teach. If in his youth he had been properly educated at a secular university and mixed with those of equal ability but wider outlook than his own, he might have grown up in his faith, not grown out of it. In what was, to me, one of the few moving sentences in his book, he says, Psychologically I could have reached a genuinely personal faith in the Roman Church only by passing through apostasy.” Perhaps we all have to do this in one way or another. On the surface Mr. Davis writes calmly enough, but there is an undertow of resentment, even bitterness, the bitterness of a man who put his trust in a God that failed.

Reading his account of his dying years as a Catholic, I was constantly struck by his intellectual narrowness, indeed naïveté. He tells us that when as Professor of Dogmatic Theology he was expounding the doctrine of the papal primacy he did not worry about the biblical and historical difficulties it raised, and that not until the very end was he struck “by the sheer exorbitance of the papal claim.” This is recorded merely as a stage in his development, which he does not seem to realize was in many respects an arrested one. And it has left its mark on him. Even now he shows only a conventional awareness of a religious agnosticism which could, intellectually, make mincemeat of his present position.

Advertisement

It will not do just to point out that Mr. Davis swallowed a fundamentalist Catholicism whole and has vomited it likewise. His book raises far more questions than that. I am more concerned here with his intellectual indictment of Catholicism than with his charges of corruption. It might be said that owing to the rise of an articulate laity together with the pressures of agnostic humanism and modern newspaper publicity the Church is far less corrupt than it ever was. But suppose for the sake of argument it is indeed the negation of God erected into a system of government. What does Mr. Davis offer us in exchange?

Pitifully little. The same logic and honesty which enables him to perceive that much of what is happening in the Roman Church cannot be reconciled with its teaching prevents him from taking refuge in Anglicanism, Lutheranism, or any resting place between Rome and extreme Protestantism. His positive suggestions are far from clear, but if I understand him rightly, when people are more enlightened the entire bag of tricks will be swept away. No Pope, no hierarchy, no bishops, no priests, no Mass, no fixed sacraments, no established creed, no authority, no common body of doctrine—no comment?

Not at all. A stale argument is not necessarily a false one. My fundamental quarrel with Mr. Davis is not that these suggestions are unworkable, nor that they are similar to those of the early Protestant radicals. On the contrary, what I object to is their dissimilarity. Radical Protestantism was myopic, but it was deeply religious. It wished to destroy those identical institutional forms which Mr. Davis now so obsessively hates, not because they stood in the way of man’s “own becoming” but because they did not reflect the omnipotence of God. Nor did the Protestant radicals share Mr. Davis’s shallow optimism about humanity. To them, sin, death, judgment, hell and heaven were just as real as eating or sleeping.

Mr. Davis remarks that many Catholics now have no definite beliefs about their Church and its distinctive doctrines, no clear ground upon which to base their faith. Since the breakdown of Catholic structures this is only too true. It was said in print while Mr. Davis was still professing dogmatic theology. He recognizes that “personal commitment to the Christian faith is meaningless without doctrinal content.” We are entitled, then, to ask him what this doctrinal content is. What is this Word, supposed to be deduced from common worlds of meaning, the historical tradition of Christian belief, doubtful Scriptural evidence, and the Holy Spirit hovering over “creatively disaffiliated” groups?

A Question of Conscience contains contradictions and inconsistencies which the attentive reader will soon discover for himself. In his last paragraph the author endorses an opinion which, taken out of context, reads like a preposterous howler. It spoils his peroration, and should be deleted. We must not lose sight of the fact that, however much Mr. Davis’s arguments can be turned against him, he has put his finger on a vital spot when he says that only too many Catholics slide out of difficulties by calling a plain contradiction “doctrinal development” or “fresh new insights.” Such Catholics, the author maintains, remain in the Church at the cost of their intellectual integrity. Those few who do have the clear-sightedness to accept the fact that they are denying Catholic doctrine must give better reasons than any he has met for not following his example.

DR, KÜNG wrote his latest book The Church before he had learned of Mr. Davis’s decision. “And precisely because it was not written as an apologia,” he has remarked elsewhere, “it may better perform this service.” In fairness to Mr. Davis, I must say that I do not think it altogether does.

In a sense it was Dr. Küng who laid the egg which Mr. Davis has hatched. Dr. Küng is a Swiss-born Roman Catholic. He was ordained priest in 1955, and at the age of thirty-two became Professor of Fundamental Theology in the Catholic Faculty of the University of Tübingen, where he is now Dean. His work on Karl Barth, an attempt to reconcile Catholic and Lutheran doctrine on Justification, is always described as monumental. It was not, however, Dr. Küng’s scholarship that brought him to the attention of the public, but his boldness in saying what a number of people had long been thinking. His book The Council and Reunion (1961), which Mr. Davis tells us he read with a thrill, appealed to a wide audience. So did his slighter books, That the World May Believe, and The Living Church. He has followed up his writing by a series of lecture tours in England and America.

Advertisement

Dr. Küng’s position is—one should say was—unusual. He is what might be termed a Catholic Evangelical. However, since he is well aware of the dangers of a false synthesis, on the whole his thought has tended toward a more Protestant understanding of Christianity than a Catholic one. Au fond, he dislikes hierarchy almost as much as does Mr. Davis. He is less than enthusiastic about the modern papacy, has played down infallibility, and is skeptical, not to say a little cynical, about the uses and abuses of clerical authority. As sensitive as Mr. Davis to the necessity of making the Church a visible community of love and truth, he is more realistic about its achievement.

“What the Church needs above all today,” he was writing long before this had become a popular slogan, “is honesty, the honesty to make a just assessment, without illusions…and secondly courage; the courage to say in season, out of season, what the situation demands…even at the grave risk of making oneself unpopular.” This program entailed some very forthright criticisms of the Church in action, and, if their implications are understood, some far more damaging conclusions about many accepted Catholic doctrines.

It was only the rapid change in the theological climate which he himself had helped to create that enabled him to attend the Vatican Council as an expert. Since then the barometer has been rising and falling at such an alarming rate that there is no knowing whether we shall end by congratulating Dr. Küng on his appointment as Head of the Doctrinal Congregation or be reverently fishing his ashes out of the Tiber. It has just been reported that the Vatican has issued a monitum or warning about The Church, somewhat tardily forbidden its translation from the German, and requested its author to report to Headquarters. Its author has declined.

The Church is not one of Dr. Küng’s popular books. It is a long and detailed work of scholarly recapitulation written for a more specialized audience, and ought to be read after his equally specialist Structures of the Church, or at least with it in mind. His purpose is to examine the essential nature of the Church as it manifests itself in various historical forms. We must cling neither to any past expression of Christianity nor fall into the equal error of so adapting Christianity to present needs and theological fashion that it loses any objective content. “The only measure for renewal in the Church,” he writes, “is the original Gospel of Jesus Christ himself; the only concrete guide is the Apostolic Church.”

This means we are dependent upon the findings of the biblical scholars, and a large part of this long, learned, and illuminating book is devoted to a detailed examination of the probable structures of the primitive and sub-apostolic Church and its very varied theologies. It is impossible to do justice to the nuances of the author’s arguments here. What follows is of necessity rather stark.

DR. DAVIS would say that Dr. Küng has no right to call himself a Roman Catholic. Certainly, the author queries, on historical or theological grounds, a number of doctrines central to Roman Catholicism as the world has known it. His views on the institution of the Papacy, the Apostolic Succession, the validity of the sacraments are not far from Mr. Davis’s. Dr. Küng rejects and regrets that understanding of the Eucharist which developed the Lord’s Supper into the Catholic Mass. His views on the sacramental presence are what, for the sake of convenience, we must call Protestant. He accepts a pastoral ministry but not an ordained priesthood in the traditional sense. All this strikes at the heart of Catholic worship as we have seen it. The fundamental problem, however, is not that what was once thought to be essential to Catholicism has, in the author’s opinion, turned out not to be. It is, are these interpretations true? Since Dr. Küng has questioned the living authority of the Roman Catholic Church up to the Second Vatican Council and seems to have retired to the shifting sands of biblical criticism one wonders if he has provided sufficient criteria for us to judge.

No one can doubt that, if the Communist countries were allowed free speech, free elections, and a free press, their system would collapse in a night. Whether the essence of Marxism could survive the breakdown of its structures is another matter. Similarly, no Catholic in the past doubted that once Rome abandoned its claim to be the one visible Church which alone had Christ’s authority to teach it would dissolve into doctrinal chaos and drag what was left of the Christian world with it.

Mr. Davis, in A Question of Conscience, accuses the Catholic Church of just such an abandonment. He is supported by Dr. Küng whose chapters on the unity of the Church are among the most interesting and subtly argued in his book. He suggests that in essentials the Church is already one. While he recognizes that historically the Roman Church is the mother of Christendom, the theological claim of any existing community to be identical with the Church of Christ is arrogant, a sign of pharisaical self-conceit, self-righteousness, and impenitence.

Nothing can better illustrate the immediate consequences of such views and the price we are paying for Christian reconstruction than the fact that The Church carries the imprimatur, or declaration that it is free from doctrinal or moral error, from Bishop Casey, Auxiliary of the Archdiocese of Westminster. Yet the well-known theologian Bishop Butler, Auxiliary to the same See, recently has denied Mr. Davis’s allegation and reasserted as basic to Catholicism those very arguments which, with Bishop Casey’s approval, Dr. Küng here categorically rejects.

Mark Pattison rather unkindly remarked that Newman used the resources of reason to prove that reason had no resources. It is difficult to avoid the conclusion that Dr. Küng, in order to show that the Church is now to be believed, has to argue that for the greater part of its history it was not. He has too profound a grasp of his subject to reduce Christianity to mere moral activity. It may be thought doubtful, however, whether the basis of his Church is broad or deep enough to withstand the full force of unbelief; whether it is possible to reconcile his equalitarian structures with any meaningful form of papacy or episcopacy; or whether the kind of worship he favors will awaken that consciousness of God in the human heart which was the supreme achievement of Catholic Christianity.

MR. DAVIS ought to regard Dr. Rosemary Ruether with ambivalence. Since she leaves the reader doubtful whether she believes in fundamental Christian doctrines, he would think it ridiculous that she should call herself a Roman Catholic; on the other hand her book is an attempt to give religious and intellectual coherence to the kind of amorphous groups he advocates.

Dr. Ruether teaches Church History at George Washington University and Theology at the School of Religion, Howard University. She contributed an essay to a symposium on Contraception and Holiness, and writes regularly for various Catholic journals. She has associated herself closely with the “underground church” which has received some newspaper publicity and whose nature will become apparent in a moment. Dr. Ruether is writing what she calls, legitimately enough, “post-ecumenical theology.” In other words, theology about the collapse of theology.

Her style is unfortunate, and sometimes barely comprehensible. Perhaps because she is too intelligent and perceptive to be totally unaware of the inadequacy of her own theories she seems to cover up by using more and more frantic theological gobbledegook.

This is a pity. Dr. Ruether has something to say. She is a realist. She recognizes that the situation has moved far beyond the question of institutional reunion. She rightly points out the relativity of Church structures, though surely she is wrong in concluding that therefore it does not matter here and now what they are. She sees that concern with the material world and passionate protest against social injustice is a vital part of the Christian witness. She understands well enough the urgent need for a theology of the secular. What she has given us is secular theology. Since this is a contradiction in terms, it is no wonder that The Church Against Itself reads more like a brilliant skit on the Catholic avant-garde than a serious attempt to construct Mr. Davis’s new form of Christian presence in the world.

Her main contention is that Christianity, having been cheated in its eschatological expectations, i.e., the immediate coming of the Kingdom of God, proceeded to construct ecclesiastical institutions which it came to identify in some way with Christ. So what was relative became absolute, the tension slackened, and the Kingdom receded into a celestial haze. In order to show how this happened the author takes us for a lightning tour around the theological battlefields, ending up, appropriately enough, with a discussion about the “death of God.”

We must now, the author argues, bring the Kingdom back into the center of our existence. This must be done not by leaving the Church of our baptism, but while still adhering to it, joining the “true church.” This “free-floating Christian community,” known more popularly as the underground church, is gathered from those of all denominations or none. It goes about doing good, getting together for prayer in fields and streets, and breaking bread on kitchen tables without “regard for the parochial boundaries of the ‘church of this world.’ ”

One can only draw attention to the central defect of this approach. If it seems at first to have nothing to do with the underground church, in fact it has everything. “…while Catholic Christianity,” Dr. Ruether writes in a typical passage, “resolved the dilemma of historified eschatology by de-eschatologising history, existential Christianity approaches the same problem by dehistorifying eschatology.” In fact she has dehistorified it out of existence.

Christianity must contain what Dr. Küng calls “irreformable constants” which remain however much their expression is culturally conditioned. If we think otherwise we would have to say the Gospels are indistinguishable from The Thoughts of Chairman Mao. Christianity is by its nature a two-worldly religion, postulating an essential difference between the sacred and the profane. Dr. Ruether, in her much needed attempt to make the tension between these two worlds fruitful, has in her emphasis, if not in her mind, obliterated one altogether.

“The Freedom Movement,” she writes in a revealing passage, “is in reality the present equivalent of the Gospel.” Herein lies her fundamental mistake. What she has done is to identify the Christian faith entirely with its social application. This application may not in fact differ from that of an atheist. When her book is stripped of its religious vocabulary we get the impression she is teaching a noble materialism. In the name of the Spirit the Spirit is denied. In the name of theological realism, theology is dissolved. We are confined to one dimension. No longer allowed to “see eternity the other night” our eyes must be exclusively directed to a world which, for a Christian, makes no sense unless it is penetrated by an order of spirit distinct from itself; a spirit which is both the ultimate reality and the ultimate goal of all human striving.

This impression is confirmed, not lessened, by reading Dr. Ruether’s book for young children entitled Communion Is Life Together. Again, one must salute her intention but not its execution. Under the cloak of religious imagery the Kingdom of God is interpreted as an earthly utopia, the mystery of the Incarnation reduced to a philanthrophic ginger group.

Let us imagine, impossibly, that by means of Dr. Ruether’s “pneumatic communities” and trans-denominational “agapic relationships” man could totally eradicate poverty, injustice, racialism, natural disasters, ill-health, violence, old age—what then? “Thou hast made us for thyself, O God,” Augustine writes in a famous passage, “and our hearts are restless till they rest in thee.” That, expressed in one way or another, is the authentic voice of religion, whether Jewish, Christian, Buddhist, Mohammedan, or so-called pagan. To allow it to be silenced by the din of falling masonry would be humanity’s final apostasy.

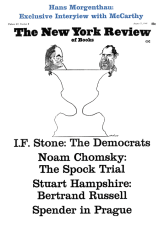

This Issue

August 22, 1968