To the west of Africa, far distant in the vast reaches of the ocean, lie scattered bits of land, the Atlantic Islands, that in the years since their discovery have attracted visitors with many and diverse interests. Among these, David Bannerman, ornithologist and traveler, in three previous volumes in turn has written of the birdlife of the Canary Islands and the Selvagens, of Madeira and its minor satellites, and of the Azores. Now with the assistance of Mary Bannerman, his wife, also a serious student of birds, he presents an account of the birdlife of the Cape Verdes, equal in attraction to its predecessors.

Far out at sea, off the most western point of the African continent, the ten main islands and five rocky islets of the Cape Verdes comprise only 1,557 square miles of land. When first reported, during the voyages of the mid-fifteenth century, man in his spread over the earth had not reached them, as their only major inhabitants were birds.

The voyager Cadamosto in his travels reported that he had seen the Cape Verdes in 1456, but this has been disputed. It seems more certain that they were sighted first by Antonio da Noli, perhaps in company with Diogo Gomes, about 1459. Portuguese authorities, who now control these islands, assign the discovery to these two, but list the date as May 1, 1460. It is definite that Portuguese settlers came to the island of São Tiago in 1462, and there established the settlement of Ribeira Grande. Ruins of their ancient buildings, now called Cidade Velha, still remain near the present capital city of Praia. Two centuries later, in 1683, the traveler Dampier described the larger islands of the group as well inhabited, with extensive plantations, and many cattle. By that time the Cape Verdes had become a regular port of call for vessels on long voyages from Europe to the East Indies or South America, that stopped there briefly to replenish water and other supplies.

Aside from mention of “doves,” which early voyagers described as abundant, and so tame that large numbers of them were killed with sticks, there was little noted of the wildlife of the Cape Verdes until a Minister of Marine sent a naturalist, João da Silva, to the islands. From 1784 to 1789 he made collections that were sent to the Ajuda Institute in Portugal. So far as the history of the birds is concerned, those included in these early collections have disappeared. The first scientific record of a bird was reported by Charles Darwin, who on the voyage of the Beagle visited São Tiago in January 1832. From Darwin’s collection, sent to England, John Gould in 1838 named the small native rufous-backed sparrow as a distinct species. This is allied to our familiar house sparrow, now abundant throughout America as an introduction from Europe.

Following several rather casual references over the following years, an English ornithologist, Captain Boyd Alexander, in 1898 published a detailed list of the birds that included the resident species with addition of fifteen kinds found as passage migrants. Among those who followed as bird-minded visitors, mention may be made especially of a party from the Cleveland Museum of Natural History in 1923 and 1924, traveling in a sailing vessel, the Blossom, named for Mrs. Blossom of Cleveland, Ohio, financial backer of the expedition. The brief previous story of this venture has been a narrative account by its leader, George Finlay Simmons, in the National Geographic Magazine in 1927.

Dr. Bannerman, through correspondence with Simmons’s sons, has assembled a record of the expedition, its difficulties and its itinerary. The latter includes a table of the dates on which specimens were collected on thirteen of the islands. In later years when policy in the Cleveland Museum changed to one devoted to the educational activities and displays usual in a city museum, and gave up most of its study collections of scientific specimens, those from the Cape Verde expedition, through the interest of Mrs. Blossom, were transferred to the Peabody Museum at Yale University.

The Cape Verdes in these modern days have developed no tourist appeal so that a visit to them is not a simple undertaking. Views of the islands from the sea as the Bannermans returned from lengthy voyages around South America had awakened their interest, but arrangements for a visit proved unexpectedly difficult. When finally they secured steamer passage to São Vicente, which they planned to use as a center for visits to other islands, the only small inter-island steamer had been wrecked, the inter-island plane had crashed, and no other regular transportation was available.

Mrs. Bannerman in a chapter taken from her diary gives a graphic account of their visit. In this remote island world, the two visitors from Scotland were received graciously and aided effectively by the few European families. To the local population they were a major attraction, greeted always in friendly manner, but often overwhelmingly, by the crowds that came to surround them.

Advertisement

On São Vicente, established in a house lent them by the British-operated Cable and Wireless company, they encountered immediately the gusts of the almost ceaseless trade wind that day and night carried clouds of dust. As this is a dry island, its main water supply came daily by boat from another island, Santo Antão. That for drinking and cooking was brackish and heavily chlorinated. Local transportation was difficult, available partly in private cars of friends, and partly by taxis for hire, few in number and expensive. The daily journeys of the ornithologists were mainly to small bays along the coasts, varied by visits inland, where birds were relatively few.

In February they were able to visit the island of São Tiago, where Praia is the main seat of the government. Here they were more sheltered from the steady beat of the trade winds, and there was less dust as the island was better watered. Around the plantations, and in the shrubbery of the valleys, smaller birds were common and interesting. One warbler, the blackcap, often appeared to have an orange throat, stained from the pollen of the orange blossoms over which they were feeding.

A second journey, more adventurous, took them to Santo Antão, traveling with an official party on a small tug over tumultuous seas. By jeep they crossed a mountain pass to a small inn that had been staffed to receive them. The visit was a welcome change, but soon they were back on São Vicente and then en route to England.

Most remote island groups are restricted in the number of species in their fauna, to which the Cape Verdes are no exception. Among the birds there are forty-three kinds that are found resident and nesting. The color plates illustrate thirty-two of these. Two, a cormorant and a flamingo, are no longer present. Three others nest only occasionally. Twenty-three are of races peculiar to the Cape Verdes, differing in varying degree from relatives elsewhere. The cattle egret is a recent immigrant, as it is in the Americas.

Part of the peculiar forms have their relatives to the north in western Europe. Only a small number have their affinities with western Africa. In addition to these, sixty-two migrants and winter visitors have been found, twenty of this number having been recorded in the Cape Verdes for the first time by the visit of the Bannermans.

The avian species of the second volume, the hummingbirds, in contrast to the feathered inhabitants of the Cape Verdes, are peculiar to the Americas. Their more than 300 species are widely distributed from the southern tip of South America to Alaska, with their greatest abundance in the tropics and subtropics of the northern Andean area. Their number diminishes steadily northward, so that only seven have their main nesting area in western United States and Canada, and only one is found regularly in the eastern part of North America. Most members of the family show iridescent plumage, with males of many displaying crests and brilliant colors. The majority are of small size, the bee hummingbird of the Antilles, the smallest, being only two and a quarter inches long.

As a group, hummingbirds live on a mixed diet of small insects and spiders captured in large part in flowers that they visit constantly, with the addition of the sweet nectar that they secure in quantity from these same blossoms. In return, in this feeding, hummingbirds serve their plant hosts through the transfer of pollen by which the flowers are fertilized and so produce their seed.

The Grants, both skilled professional botanists and interested in this exchange between bird and flower, through studies over a period of years, have established a list of 129 plant species of western United States that are adapted in form for such feeding and pollination. These they call hummingbird flowers. For forty-one they have definite evidence of regular fertilization by the birds. As the others have flowers of similar type, they suggest a like mode of pollen transfer by the birds.

Hummingbirds in their feeding are attracted definitely to flowers that are red and yellow. These are the colors of the hummingbird flowers, especially the kinds called Indian paint-brush or painted cup (genus Castilleja). In addition to the color, these attract through the abundant nectar produced at the bottom of the elongated corollas. The bills in the seven hummingbirds of the western United States range in length from seventeen to twenty-one millimeters (from a quarter to a little more than three-eighths of an inch). In addition, the end of the tongue may be extended beyond the tip of the bill, and so assist the feeding. The length of the tube in the hummingbird flowers corresponds closely so that the nectar (and the accompanying insects) are readily accessible to the birds. Only a few kinds of long-tongued bees may compete with them. As the bees are color-blind, they seek flowers for feeding largely through the sense of smell. As most of the hummingbird flowers are odorless, there is little competition between insect and bird.

Advertisement

Also bees, and their companion butterflies, feed mainly by perching, and so require flowers more or less flat in form to provide a landing platform. The longer, tubular blossoms are readily available to the birds, as they hover during feeding. The only hummingbird competitors are thus the hawk moths that use their long extensile proboscis as the bird does its bill. As the hummingbirds feed they bring fertilization to the flowers through the pollen that clings to their head feathers or bill.

The close relationship between the birds and the hummingbird flowers is indicated by the fact that in western United States both are mainly absent from areas of open grassland, deeply shaded forests, and above high timberline in the mountains. The authors make interesting speculations as to ancient development of this relationship through natural selection of both bird and flower to their mutual advantage.

The twenty color plates at the end of the volume all carry between three and six separate figures. These are interesting and serve to demonstrate technical points discussed in the text, those of the flower series more effectively than those of the birds. The latter in the main are small. Both sets are useful but in method of reproduction do not compare with the average in modern color reproduction.

The final book in this group concerned with birds differs completely in that it is a presentation of paintings, each devoted to a single species, the work of one of the younger artists in this field. Its offering of esthetic pleasure to those who enjoy bird portraits is in contrast to the more informative pages of the other volumes. The title, Birds of the Eastern Forest, may be a bit confusing as the first bird depicted is a grebe, followed by several herons, all aquatic in habit, not to be regarded as typical forest birds. The title, the author collaborator explains in his introductory paragraphs, refers to the geographic area of eastern Canada and adjacent United States, one with diversified habitat. The selection of species is intended to be representative of the various families in systematic order. Evidently there is to be a second volume to include other species.

Each color plate and its text is preceded by a page of the artist’s field sketches that show attitudes and pattern of activities from which the finished painting was designed. Some are interesting, others merely indefinite, confused lines.

The text, opposite each plate, in double column, is taken in part from a brief bibliography of standard reference works at the close of the volume, and in part from personal observation and anecdote of the author. On the whole, this material is fragmentary, often filling only part of a page, with the right hand margin set in irregular, broken line.

The paintings are pleasing in composition, lifelike and attractive. The volume, an enlarged quarto (10 × 13 1/4 inches), presents fifty-two species, all in large size with detail in background sufficient only to give support for the bird—a few water plants for aquatic species, a branch as a perch for those at rest, or only the white of the page for those depicted in flight.

The artist indicates that details of color and marking were, as is proper, taken from museum study skins, for which the place, date, and sex are listed. A few of the presentations may be open to slight criticism from a professional eye. The turkey vulture is in a most uncomfortable pose, with head and foot not in proportion with the wings. The male downy woodpecker lacks the black bars on the outer tail feathers. Thus, at first glance, it may be mistaken for its larger cousin, the hairy woodpecker of similar color but with tail unbarred. The eastern kingbird is poorly posed with wings and tail not in proportion. These in a sense are minor matters that do not detract from the general excellence of the book. This, as a whole, displays the hand of one clever and experienced in his field. The volume is one to be treasured and owned by those who enjoy birds, not as a work of reference.

This Issue

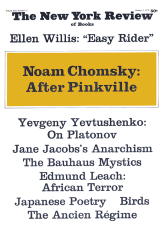

January 1, 1970