I

In 1821, when Pushkin was twenty-two, he wrote a long poem called Gavriiliada, which was circulated widely in manuscript but, on account of its impiety and indecency, never published during Pushkin’s lifetime. It made trouble for him in 1828, when Pushkin was already in bad odor with the authorities. The servants of a Captain Mitkov complained that their immoral master had been reading them a blasphemous poem. The captain was arrested, and Pushkin was made to appear before the military governor general of Petersburg. He denied having written the poem, but this disavowal was not accepted, and he might well have been sent to Siberia if he had not addressed a letter to the Tsar in which he is thought to have confessed and expressed the deepest contrition. The Gavriiliada appeared in print only in 1861, when the poet Ogarev had it published in London. Today it is included in all the Soviet editions of Pushkin; yet it still has so black a reputation among members of the old regime that I have found that a highly intelligent and otherwise well-read Russian friend has never been able to bring herself to face it.

The Gavriiliada was obviously prompted by the literature of the French eighteenth century, of the mockery of the Bible by Voltaire and his follower Evariste Parny. It is directly indebted, in its comic treatment of the legend of the Immaculate Conception, to Les Galanteries de la Bible and La Guerre des Dieux of the latter; and in Parny’s version of the Garden of Eden, in which Satan in the guise of a serpent is made to play a liberating role, to his Paradis Perdu.

I have just reread the Gavriiliada and I found that it did not have the charm for me that it did when I first read it. But if one comes to it after Parny, graceful and well-turned though this is, but thin and dry in the eighteenth-century fashion, one is struck by Pushkin’s faculty for making anything he touched humanly sympathetic. His Mary is successively ravished by Satan, who has transformed himself from a snake to a handsome young man; by the Archangel Gabriel, who has been sent by the Lord to prepare the way for His holiday from the routine hymns and prayers in His praise, but takes advantage of the opportunity to make love to the irresistible Mary; and finally by the Lord Himself in the form of a quivering billing dove.

All these characters are brought to life much more vividly than Parny has been able to do. The first of the seductions leads Pushkin to remember wistfully his first arousing the desires of a well-brought-up young girl; and the struggle between Satan and Gabriel is described in terms of his schoolboy wrestling with comrades. The serpent’s account of the raptures of love to which he introduces Adam and Eve seems to me more attractive than those of either Milton or Parny:

И не страшась обжественного

гнева,

Вся в пламени, власы раскинув, Ева

Едва, едва устами шевеля

Лобзанием Адаму отвечала.

is an already masterly example of Pushkin’s famous skill at alliteration, and the “Едва, едва” that follows “EBa” is an example of Pushkin’s power, later brought to such perfection, of making the language itself represent the thing described—in this case, Eve’s mouth with lips open from being kissed. This is echoed, as it were, when Eve succumbs to Satan:

Она молчнт: но вдруг не стало мочн,

К лукавому склонив свою главу,

Едва дыша, закрыла томны очн,

Вскричала: ах!.. и пала траву…

But in general the vocabulary is a little repetitious in comparison with Pushkin’s more mature and tightly economic style.

II

“The Gypsies,” of 1824, is a striking example of Pushkin’s characteristic style. It concentrates in twenty pages a drama that seems to cover enough ground to have required many more. But I mention it because it seems to me to have been, even by Russians, rather imperfectly understood. Aleko, the central character, has fled cities and civilization in order to live with the gypsies, where he is able to enjoy a new freedom. A gypsy girl named Zemfira has found him in a waste place and brought him home to her father. Aleko loves her and lives with her; he stays with the gypsies two years. But she arouses his apprehension when he hears her singing a gypsy song in which a young woman defies her old husband and announces that she is now in love with a young man who is bold and hot-blooded. It presently becomes plain that Zemfira herself has taken a lover. Aleko wakes up one night and finds she is not by his side. He goes after her and stabs both the lover and her. The father rebukes him and orders him to leave. The gypsies live in lawless freedom; they will not tolerate murderers. Aleko is not fit for their wild life. He wants freedom only for himself. The gypsies depart like a flock of cranes and leave Aleko alone like a wounded crane on the steppe.

Advertisement

But in summarizing this story, I have omitted one very important circumstance that I find is often overlooked. When Zemfira brings Aleko back with her, she explains, at the very beginning, that he is being pursued by the law—“Ero преследует закон.” A later conversation with the old man, when Aleko is worried about losing Zemfira, makes it plain that the gypsies are pacific whereas Aleko is revengeful and violent. The old man long ago lost the woman he loved when he let her go off with a man who belonged to a different band; but Aleko protests that he would never stand for this: “I am not like that. No, I should never without fighting renounce my rights!” He would hound his enemy to his death and laugh fiercely when he had been destroyed. It is thus intimated, it seems to me, that Aleko was fleeing from the law on account of having committed a crime of violence and that he will inevitably commit another. The way that this is indicated, by a series of touches and never too explicitly, is entirely typical of Pushkin. The old man has already told Aleko the story of an outsider who had come among them but could never be at peace because he believed that God was punishing him for a crime. The incomparable Epilogue clinches this:

Но счастья нет и между вами,

Природы бедные сыны!

И под издранными шатрами

Живут мучительные сны,

И ваши сени кочевые

В пустынях не спались от бед,

И всюду страсти роковые,

И от судеб зашиты нет.[But even among you there is no happiness, poor children of nature! And under the tattered tents there still dwell tormenting dreams, and your wandering shelters in the wilderness provide no sanctuary from sorrows, but everywhere are predestined passions, and from the fates there is no escape.]

The last two lines show Pushkin at his most trenchant; in translation they can hardly seem anything but flat. But the snap of судеб and нет which follows the description of the gypsies roving peacefully away in the wilderness, chops off grimly the drama of Aleko. I have inadequately tried to render it in matching escape with fates.

III

In 1922, the poet Vladislav Khokasevich published a little volume called Articles on Russian Poetry in one of which, “Pushkin’s Petersburg Tales,” he discussed a curious production which seems of such interest and importance that one wonders at never having found it mentioned by anyone else. In a Russian paper called The Day, there was reprinted in December, 1912, by the Pushkin scholar P.E. Shchegolev, and again in the January, 1913, number of a magazine called Northern Notes, a story which had first appeared in 1829 in a miscellany, an almanac called Northern Flowers. This was “The Lonely Little House on Vasilevsky [Island],” “Уединенныӥ Домик на Васильевском” signed Tito Kosmokratov.

One evening in 1829, at the Karamzins’, Pushkin had told a story which, according to the account of Pushkin’s friend, Baron A.A. Delvig, considerably affected the ladies and made such an impression on a young writer named V.P. Titov, who was there, that he was unable to sleep that night and later wrote the story down from memory. He showed his version to Pushkin, who amiably made some corrections in it and gave him permission to publish it. Now, this strange story is quite plainly the original nightmare fantasy from which, as Khodasevich says, were to grow the three stories later written and published by Pushkin as “The Bronze Horseman,” “The Little House in Kolomna,” and “The Queen of Spades.” These, it seems, have been known as the “Petersburg Tales,” though there is no direct connection between them, and in “The Queen of Spades” the city “as such does not play any role.” And yet a connection, although invisible, was felt to exist between them, “as astronomers are able to guess at the existence of a star which their optical instruments cannot yet reach.” That invisible connection was the story written down by Titov and neglected for many years in the files of the 1829 miscellany in which it had been published.

This story is about a young man named Pavel. He is in the habit of going to see a distant relative, a widow who lives in a little house in the suburb of St. Petersburg called the Vasilevsky Island. The widow has a daughter named Vera, to whom Pavel is “not indifferent.” But he makes friends with a rather mysterious youth called Varfolomey, who never goes to church and who gets money from some unknown source. He exercises “over the weak young man an irresistible power” and persuades him to take him to see Vera and her mother. Varfolomey has designs on Vera, but her instinct is not to like him, she prefers Pavel.

Varfolomey convinces Pavel that he ought to go into society and takes him to the house of a countess of his acquaintance, a beauty, to which her friends come in the evenings to gamble. These friends wear high wigs and baggy Turkish trousers and never take off their gloves. It is evident—though not to Pavel—that they are devils concealing their horns, hoofs, and claws. In their company, Pavel forgets about Vera; but Varfolomey has been working on her and Pavel finds that she now treats him with coldness. He demands an explanation of Varfolomey, and the latter declares that Vera has fallen in love with him. Pavel makes a lunge at Varfolomey but is knocked down by a violent though painless blow. When he comes to, Varfolomey has disappeared, and Pavel hears ringing in his ears his last words, “Be quiet, young man: you’re not dealing with a brother.” (“Потише, молодоӥ человек, ты не с своим братом связался.”) Going home, he finds a letter from the countess, giving him a rendezvous on the back stairs of her house for the following night.

Advertisement

When he goes there, the beautiful countess is alone, but just as he is about “to taste his bliss,” the chamber-maid knocks on the door and says there is someone to see the young gentleman. When Pavel goes down to the reception hall, he is told that the caller has left. He returns to the lady upstairs, but the same thing occurs again. There is nobody outside the door—nothing but the silent falling snowflakes. The third time, he sees a tall figure in a cloak, who beckons to him and vanishes in an alley.

Pavel is up to his knees in snow, and he signals to a cabby and orders him to take him home. Presently he comes to realize that he has been driven out of the city and remembers the stories of cabbies who have cut their customers’ throats. “Where are you taking me?” No answer. He sees that, in large, strangely formed figures, the cab is labeled “666”—which he afterwards remembers is the number of the Beast of the Apocalypse. He strikes the driver with his stick and feels that he is beating not flesh but bones. The driver turns his head and reveals a grinning skull, which repeats, in a blurred voice, the words of Varfolomey, “Be quiet, young man, you’re not dealing with a brother.” Pavel crosses himself; the sleigh overturns in the snow, and he hears a wild laugh; there is a terrible whirling gust of wind; and he finds himself alone outside the city gates.

Pavel comes to himself in his bed, and for three days is out of his mind. It now appears that Varfolomey is getting both Vera and her mother under his domination. Vera confesses she loves him. The mother falls ill and is sinking, but Varfolomey prevents them from sending for the priest on the pretext that the priest’s appearance would convince the old lady she was dying and deprive her of her last hope. She calls Varfolomey and Vera to her bedside and with a wry smile tells Vera to kiss her bridegroom. “I’m afraid of going blind, and then I should not be able to see your happiness.”

The old lady dies. But Vera, who can still pray, rebels against the spell of Varfolomey: “Obey me, Vera, don’t be stubborn,” orders the demon. “No force protects you now from my power.” ” ‘God is the protector of the innocent,’ cries the poor girl, in desperation, throwing herself on her knees before the crucifix.” “If that’s how it is,” says the demon, biting his lips and with a face expressing impotent malignancy, “there’s nothing to be done with you; but I’ll get your mother to make you obedient.” “Is she in your power?” asks the girl. “Look,” the demon answers, fixing his gaze on the half-opened door to the bedroom, and Vera seems to see two streams of fire gushing from the demon’s eyes and, in the glimmer of the guttering candle, the dead woman raises her head and with her withered hand gestures her to Varfolomey. Vera calls upon God and faints. A sound like a shot wakens the sleeping maid, and she sees that the bedroom is full of smoke and that the curtains are burning with a blue flame. Attempts to put out the fire are vain; there is a storm that is spreading the blaze.

The demon disappears. Vera wastes away, afraid that through her weakness she has been responsible for her mother’s death and damnation. Pavel leaves Moscow and goes to live in the country. He is apparently half-insane, and the sudden appearance of a tall gray-eyed man throws him into convulsions, he becomes quite mad. His servant, coming in unexpectedly, finds him trembling and protesting, “I didn’t cause her death.” Very soon he, too, dies.

One can see how the three stories mentioned above—“The Little House in Kolomna” (1830), “The Bronze Horseman,” and “The Queen of Spades” (both written in 1833)—must have grown out of this sinister fantasy (published in 1829). In both “The Little House” and “The Bronze Horseman,” as in the Vasilevsky “Lonely House,” you have a widow and her daughter living in humble circumstances, into whose household comes a young man; in “The Queen of Spades,” a young man comes to see an aunt and her niece. One recognizes in the countess of “The Queen of Spades,” with her evenings of gambling with her friends, the gambling countess of the Vasilevsky story—though the former is an old lady and the latter, we are told, a beauty. One recognizes in the statue of Peter the Great that turns its head and terrifies Evgeni by asserting its despotic authority the cabby of the Vasilevsky story who turns his head with more or less the same effect. Pavel and Herman and Evgeni all go insane. All are threatened and finally ruined. But in the story written down by Kosmokratov, the forces of Evil are everywhere. The presence of the Devil is quite explicit; in the stories that grew out of it a diabolical power is intimated only by the mention that the old countess is supposed to have known the Comte de Germain, the eighteenth-century adventurer who was supposed to have learned his arts from the Devil.

The most curious of these stories is “The Little House in Kolomna.” Here the widow loses her cook and engages a woman who is willing to work for whatever they choose to give her but who turns out to cook very badly. This cook is actually a young man, whom the daughter has smuggled into the house. The old lady is horrified to find him shaving. He disappears, and that is the end. Pushkin tells you in the last stanza that the only moral of the story is that it is dangerous to engage a cook who is willing to work for very little, who was born a man, and to whom wearing a skirt is not comfortable or suitable, and who will give himself away by shaving his beard. “You won’t be able to get anything more out of my story.” But Khodasevich seems to believe that Pushkin is referring to the earlier story which has in common with “The House in Kolomna” that both describe dangerous invasions of the modest homes of widows. I am inclined to think, however—I may have seen this suggested somewhere—that Pushkin, in the cramping conditions which Nicholas had imposed on him by making him a court official and by subjecting him to espionage and censorship, is expressing here, as in others of his works, his protest against this humiliation, which amounts to being made to pretend to a feminine role. He is warning of the dangerous possibilities of forcing a spirited man of genius to play the part of a bad cook. So the Evgeni of “The Bronze Horseman” shakes his fist at the “idol” of Peter the Great, who has founded his city on a swamp and exposed it to such floods as have destroyed Evgeni’s sweetheart whom he was hoping to marry. Evgeni cries, “You’ll reckon with me yet!”

The forces of Evil were closing in on Pushkin. They dragged him down by the fatal noose of the insulting anonymous letters that spurred him to the duel with D’Anthès. But where do the devils come from that pursue Pushkin’s first victim Pavel? What had Pavel or the widow or Vera done to incur their malice? Pavel is called weak, to be sure; and after the general catastrophe, both he and Vera feel guilt—she for having exposed her mother and having caused her death and he for having caused Vera’s death. Old-fashioned Orthodox Russians seem to have felt the devils all about them. I have heard of the wife of a priest who, though living in the United States, always wore a scarf over her head and sat with her back to the wall to keep the demons out of her ears. In Turgenev, the Power of Evil, for no intelligible reason, always seems to come in from the outside. In Dostoevsky, it exists in the men themselves. Which of the brothers Karamazov was guilty of the murder of their father? But in Бесы, The Fiends, which Constance Garnett called The Possessed, the character based on Nechaev, the ruthless revolutionist who so hypnotized Bakunin, is an absolute force of Evil who could not conceivably be anything else.

Tito Kosmokratov’s story should certainly be included in Pushkin’s collected works.

IV

It is interesting to contrast two short personal poems by Pushkin and by Alfred de Musset which were composed in moments of melancholy:

Пора, моӥ друг, пора! покоя сердце просит,

Летят за днями дни, и каждыӥ час уносит

Частичку бытия, а мы с тобоӥ вдвоем

Предполагаем жить, и глядь, как раз умрем.

На свете счастья нет, но есть покоӥ и воля.

Давно завидная мечтается мне доля—

Давно, усталыӥ раб, замыслил я побег

В обитель дальную трудов и чистых нег.J’ai perdu ma force et ma vie,

Et mes amies et ma gaíté;

J’ai perdu jusqu’à la fierté

Qui faisait croire à mon génie.Quand j’ai connu la Vérité,

J’ai cru que c’était une amie;

Quand je l’ai comprise et sentie,

J’en était déjà dégoûté.Et pourtant elle est éternelle,

Et ceux qui se sont passés d’elle

Ici-bas ont tout ignoré.Dieu parle, il faut qu’on lui ré- ponde.

Le seul bien qui me reste au monde

Est d’avoir quelquefois pleuré.

Pushkin’s poem was written probably in 1834, three years before his being goaded into fighting his fatal duel with D’Anthès; Musset’s when he was only thirty and had still seventeen years before him. Musset’s, without his knowing it, had been picked up from his bedside table by a friend with whom he was staying in the country. Both are now among the best-known of their poets’ lyrics.

What is striking about these two pieces is that Musset at thirty feels that he has lost everything, even his belief in his genius, and that the only good thing now left him is sometimes to have wept. Pushkin, being slowly crushed by censorship, by involvement in the life of the court (he was trying to resign from his official position), and by the incomprehension and indifference of his wife—is she the “friend” he addresses and begs to come far away with him to a life of tranquillity, reminding her that every hour carries away a bit of existence and that although “we propose to live, behold, on the contrary, we are going to die”?—nevertheless looks forward to escape and freedom for devotion to his work. Alfred de Musset already is saying farewell. Pushkin, although rather wistfully, on the eve of extinction, is still full of creative vitality and planning to find leisure for productions that, one assumes, like those of the past, will express something more than his sorrows.

V

It is ironic to find today among Pushkin’s notes of 1830,

Шпионы подобны букве ҍ. Нужны в некоторых только случаях, но н тут можно боз них обоӥтнться, а они привыкли всюду соваться.

Ѣ is an old letter identical in sound with e, which was abolished at the time of the Kerensky revolution.

Spies are like the letter Ҍ. Needed only on certain occasions, though even then one could get along without them, but they are always sticking their noses in.

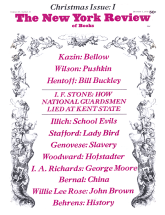

This Issue

December 3, 1970