The other day a faint breeze ruffled the unfathomable waters of the Church of England. How—if at all—should prayers be offered up for the dead? If hell is abolished, if no one has any conception of the form the Resurrection will take, if the whole Christian cosmos of nineteen centuries, immortalized in painting, poetry, and music, of death, damnation, grace, corporeal resurrection has vanished into an agnosticism so Stygian that it would have been acceptable to the generation of Victorian rationalists who foretold that it would come, what are we to do about the dear departed? Whereas in the last century and before the devout would have prayed for the souls of the dead, imploring God to show them mercy and compassion instead of dealing with them according to their deserts, today Anglican clergymen suggest that it would be more seemly to “commend” them to God and give thanks for “their life and witness.” Auguste Comte’s Positivist liturgy could hardly surpass this modest acknowledgement.

The word “witness” is a term of unction deriving from the Pauline epistles, St. Paul holding that every Christian should follow his own example and bear witness that Christ had died for him and redeemed him. Except in revivalist circles, there is today a singular lack of enthusiasm for witnessing to any Christian tenet. And yet occasionally there are people whose whole lives seem in retrospect to be a witness to goodness. Such people are not saints: saints have to retain a tough little nut of egoism inside them, and the sort of political sense which enrages their opponents as Gandhi enraged his. The witnesses to goodness are simple people, often muddled people, but serenely clear in their minds that their duty in life lies in helping those of their fellow men whom they consider to have exceptional talent, or exceptional misfortune. Or they serve causes which appeal to their sense of justice. They are the angels of radicalism—a movement which on the whole does not sparkle with the attractive, the charming, and the pure in heart.

Harriet Weaver was pure in heart. She wrote practically nothing, she let others take the lead, her role in life was to support, succor, rescue, and comfort, although she drew a curtain of reticence between herself and those she helped. She has a footnote in history as James Joyce’s publisher in England. Her life was a roll call of causes. Born into a middle-class family in the north of England, deeply evangelical, she showed the first sign of her independence by reading forbidden books so that her mother in horror removed from her hands her copy of Adam Bede on the grounds that one of the characters in the novel had an illegitimate baby and its author was living in sin with George Henry Lewes. But Harriet never broke with her parents. She compartmentalized her life. Beginning with social work in the East End of London in an organization with the characteristic title of the Society for Organising Charitable Relief and Suppressing Mendicity, she slid into the suffragette movement, broke with Mrs. Pankhurst, and founded a women’s liberation paper, the Free-woman, which became the New Free-woman, which became the Egoist….

The pattern is all too familiar, but the difference in her case was that her little magazine was to publish Pound, Prufrock, and Joyce, finally ending by publishing the first English edition of Ulysses. It was the dream of everyone who invested his personal fortune in a little magazine. To be a footnote in history! It may not be very much, but it’s more than most of us can hope for. But Harriet Weaver didn’t care about being a footnote anywhere. She was devoid of ambition, devoid of guile, wile, shrewdness, judgment, flair, or any other qualities which make for a good entrepreneur in literature. She didn’t care all that much for literature. What she cared for was talent. She saw her own task as simple. Most unjustly—in her view—she had inherited a small amount of capital which brought in a little income. She decided to devote it to helping those who seemed to have talent.

She did not scout for talent. It was on her doorstep, or did not exist. As she happened more by accident than by design to be near the center of the pre-1914 avant-garde, she had plenty of opportunity. When, even more unjustly, she inherited yet more money, she gave it to Joyce to support him in Paris. There was a bad moment when she heard that he drank—she made anxious inquiries. There was an even worse moment when he resented the fact that she should know any more about him than he chose that she should know. There was a coolness. There was a coolness later on with Sylvia Beach and with others whom she helped. But never a quarrel. As used to be said in the nursery, it takes two to make a quarrel, and Harriet simply moved out of range when guns opened up, and never took offense and fired back.

Advertisement

Much of Dear Miss Weaver is rightly spent in relating every detail of her efforts to help the artists of the literary revolution. But the person whom she spent even more time and energy helping, for the same reason, namely, to enable her talent to gain recognition, had in fact no talent at all. This was Dora Marsden, her co-editor in the days of the women’s movement, who dedicated herself to unraveling the secret of the universe.

Who in intellectual life does not know the mad metaphysician? Who has not been plagued by the man who believes that all will be made clear if, say, history is written backward and interpreted through Jung? Or proves the existence of God through an analysis of prime numbers? Dora Marsden began writing a work to revolutionize philosophy. Her articles had already become unreadable, but Harriet Weaver went on indefatigably deviling for her, looking up references, sending the first volume to a now forgotten English metaphysician, Samuel Alexander, who wrote piteous letters imploring Dora not to send the second and third volumes before he had commented on the first (which in despair at her total disregard of anything anyone had ever written on the subject, he finally did). It was Harriet who provided the money finally to print and publish the first volume. It sold four copies. The second sold none. The long tale of Harriet’s devotion to Dora Marsden, who, like the demented, rewarded her only with entreaties and reproaches, and of her refusal to become inescapably engulfed by Dora’s madness, is a study in humility, futility, and virtue.

During the war and the Twenties she had left radical politics behind her, but in the gap left by her protégés becoming famous, and in the disturbances of the Thirties, her interest in politics, like that of so many others, revived. She was converted by reading the Webbs on the Soviet Union, and became a dedicated member of the Communist Party. She made no speeches, hunted no witches, never engaged in hatchet work: she went on demos, addressed envelopes, carried banners, sold the Daily Worker. Nothing shook her faith. The purges, trials, labor camps, murder of Trotsky, Nazi-Soviet Pact, Poland, Yugoslavia, Hungary, all fell like water off her back. For her there was to be no other acceptable explanation of politics for the rest of her life, and she repeated the phraseology of faith with the same serenity and sincerity, detachment and sweet determination that had marked her relations with artists. She came to be loved by the staff of the Daily Worker for much the same reasons, and probably with greater generosity than those whom she had helped to publish.

The authors of this biography have written an excellent passage explaining her Marxism, which, they rightly say, means different things to different people. To Harriet “it offered a glorious justification of her deepest instincts and longings.” Her Victorian optimism and rationalism, her desire to be totally committed, her love of the underdog, her guilt about unearned income, her detestation of the role in economics of interest, her belief in the principle of equality, all found expression in her new creed. It was, after all, a relief from the creed of Dora Marsden, who believed that the world had gone wrong because it had shed God, who was the Great Almighty Mother Space, the Magnetic Ocean…. Harriet Weaver died secure in the faith, a renowned figure in the legend of Joyce, and without an enemy in the world, in the autumn of 1961, and Samuel Beckett said that he would think of her when he thought of goodness.

Her biographers have been attacked for the inordinate length with which they tell their tale, and it is true that no detail is too small or forgettable for them to remember and record it. There is no trace of irony, or ripple of humor in what could in other hands have been portrayed as an essay in comedy, an annex to Cranford. Yet they were right to pile on the detail and refrain from comment. To be ironical at the expense of the simple-minded and pure in heart has a way of backfiring upon those who are neither; and perhaps there are qualities which can emerge in a biography only through amassing the trivia of life. There is something disconcerting about that cool gaze, that determined chin, that open, ingenuous face, the naïve mouth of this English spinster.

Advertisement

Perhaps, after all, there was in her something of the instinct of self-preservation cultivated by the saints. She was not so soft and loving as to say nothing: when she thought it her duty to speak, even if it meant telling Joyce that his daughter was insane or his last work incomprehensible, she did so. At the very moment in the story when it looks as if she is going to be sucked underwater by the fierce whirlpools of rage and egotism and despair which surround her, she gives a little kick and swims gently out of range. By giving her heart to nobody, she had a bit of it for everyone. There is something touching in the banalities of this biography, almost as if a new way had been found in delineating goodness. She was a nonentity who continued to exist when she had left the scene.

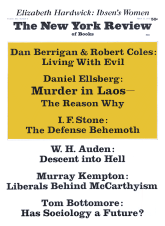

This Issue

March 11, 1971