Most of these essays are anecdotal or journalistic or slapdash, the tone both crotchety and ingratiating. They come to us, however, heavy with moral concerns since the author pretends to deep thoughts on Nothingness and the literature of Extremity. It is as if one were reading about existential anguish in the pages of The Saturday Evening Post. Here is Elliott on Proust: “Among other things, the profoundest Modern told us, Don’t be like me if you can help it. Let us honor Proust for his terrible honesty, and then try something different—perhaps something old.” But does Remembrance of Things Past really say that? Or is it merely what Elliott wishes to hear, just as he apparently wishes, once aesthetic aspects have been swept away, to consider all modernist nonconformist art and characters as cautionary tales and cautionary figures?

It is a narrow, reductive, and philistine (despite a show of erudition) approach to the intricacies and revolutionary nature of the modernist sensibility, reminiscent, here and there, of those old saws about the “beastliness of Nietzsche” or the “decadence of Gide.” Predictably it produces a tiresome irony: “I yearn to be an anarchist and tear apart our blatantly wrong society—Yippie!—and I yearn even more to be a dictator and impose my will as law.” The approach is sociopolitical or socioreligious and the autonomy of art suffers from it. “In respect of pornography and nihilism, my consciousness has expanded enough. There are things I want not to know.” Brave words. Elliott appeals to those intellectuals with conservative (not, one should emphasize, classicist) taste, who don’t want, after all, to be considered squares—which, like Elliott, they resoundingly are.

This is a long overdue introduction to gospel music. While the black blues tradition has been thoroughly mined by rock and folk musicians, gospel singers—Mahalia Jackson notwithstanding—have by and large remained unknown outside the ghettos: The Dixie Hummingbirds, The Staple Singers, Marion Williams, and Alex Bradford, for example, have rarely been heard by whites. Heilbut blames intellectual disdain of the Holy Roller tradition for the musical neglect—whites see it as the product of possessed freaks, while young blacks deplore the Sanctified Churches as a socially retrograde force. In fact these profiles of the saints of gospel do challenge the stigma of ignorance, naïveté, and Uncle Tomism attached to gospel music. Heilbut sees the collective frenzy of gospel’s moans and shouts as an expression of “spirit and community welded by art” and stresses that gospel singers (“the most underpaid in America”) minister to “winos, prostitutes, and workmen”—human wreckage with nowhere else to go. He does well by the music too, noting the stylistic similarities to soul and the “overwhelming sexual presences” of its performers and sensibly stopping short of psychologizing on ecstatic conversions and orgiastic celebrations of redemption. The rhythms and harmonies defy exposition on the printed page but this book nevertheless has useful information in it.

Hickel’s buoyant political memoir will disappoint many of those misty liberals who belatedly adopted him during the early Nixon years and later, after he broke off, championed him as an endangered species. Those looking for fresh anti-Administration material will not find it here. There is little Oval Room laundry in the book that hasn’t already been publicly washed. Hickel is a restless, self-made man whose feelings are never far from the surface, and when his initial disenchantment as a member of the Nixon cabinet grew into festering dissatistion, the frustrations blew up all over the newspapers, most of it coming out in the celebrated Cambodia letter to the President, the Mike Wallace interviews on 60 Minutes, and recriminatory White House interviews. This is yesterday’s news.

What gives Hickel’s account more than transitory value, however, is the firsthand review of his vigorous efforts for a better environment, both as Interior Secretary and governor of Alaska. In his short term in office, his achievements included: the “absolute liability” concept as applied to oil industry pollution, the historic Chevron fire case, the “Parks to the People” program, etc, (though he does frankly admit, “I could never get my hands on the mining thing”). Much of Hickel’s considerable success, as recorded here, was due to his administrative style—he bullied and inspired sluggish bureaucrats into action, tried to and sometimes did cut through governmental red tape, and refused to engage in technocratic jargon (he once asked John Mitchell, “Doesn’t anyone around here ever use the word horseshit?”). In the final section, Hickel discusses his philosophy of government and our political problems. His answer to the question who owns America is we all do, so let’s keep it clean and livable and make our public decisions in public in the public interest. This is sincere rhetoric but rhetoric all the same.

Advertisement

Using as his center the 1967 riot in which twenty-six persons died, Porambo reports on Newark before and after (it’s the same, only worse), largely through the eyes of of the relatives of riot victims who offer graphic accounts of how they died (at the hands of Newark’s graft-ridden, shotguntoting police, not the ubiquitous but elusive “sniper” of press reports and police dossiers). Officiating over moribund Newark and robbing the pennies from dead men’s eyes, so to speak, are ex-Mayor Hugh Addonizio, Police Director Dominick Spina, and assorted city council miscreants—all linked by ties of blood, bigotry, and under-the-table payoffs to Mafia-controlled gambling, narcotics, auto rackets, construction firms, etc. Porambo, a journalist from Newark, is specific with the names and addresses of victims and hustlers and unimpressed by the whitewashing police reports that were spread thick over the Hughes Report after the 1967 riot, which called the Newark Police Department “the single continuously lawless element operating in the community.”

Porambo follows the activities of LeRoi Jones, Newark’s foremost black political agitator, and Anthony Imperiale, the karate-chop vigilante from the Italian north ward, who fought it out for the soul of Newark largely by way of racist rhetoric, a struggle that served to exacerbate the black-white polarization after the riot. Toward the end, with Addonizio and company convicted of extortion, there is the promised new dawn of the Gibson election. But the dawn turns out to be false: Gibson, lacking money to run the city and at the mercy of the conservative and vengeful city council, failed to clean house, permitted the teachers’ strike, and failed miserably to stop police murders in the street.

Jones, now enjoying federal grants, dreams of a black cultural flowering (“Newark might disintegrate in crime and perversions but its black residents would make LeRoi happier by using fewer Portuguese olives”) and Imperiale blusters in impotent and illiterate rage. Meantime the city has the highest percentage of substandard housing in the country and proportionally the highest crime rate, VD rate, maternal mortality, tuberculosis, and teenage unemployment—and a current $42 to $63 million budget deficit. Porambo is energetic, angry, and tough on everyone.

A self-caricature of a new leftist attack on Kipling, Conrad, Joyce Cary, Lawrence, and Forster as, variously, apologists for empire, racists, opponents of revolutionary culture, and more or less uptight characters. Raskin mainly provides summaries of the novels, often long and sympathetic ones, but sprinkled with huffs and puffs of invective. To Raskin Kipling is full of imperialist élan while Forster never writes about orgasms and “avoids the phrase ‘the proletariat.’ ” Raskin’s catalogue of crimes is obtuse even on its own terms: George Eliot is said to have been “wary of depicting the Middle-marchers in their political and social roles.”

As a literary critic, Raskin is unsophisticated, full of schoolboy exegeses and clichés like “loss of the self.” As a revolutionary literary critic, he is absurdly pretentious. He isn’t a political thinker; consequently, he sees only the most obvious elements of colonialism, racism, male chauvinism, etc. He is incapable of identifying the political interest of Lawrence and Forster. In fact, he is a romantic in militant dress, which explains his relative subtlety in dealing with Conrad and Cary. He is also a moralist of sorts—this, not revolutionary theory, explains his enthusiastic references to Ho and Che. This is not to say that enfant terriblism is useless—think, for instance, how useful Karl Shapiro’s growls against the Eliot cult were in the Fifties—but Raskin is hardly unseating any live gods. No one should mistake this amalgam of political graffiti and literary clichés as the work of a vanguard critic.

(Notice in this section does not preclude review of these books in later issues.)

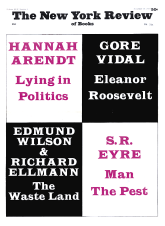

This Issue

November 18, 1971