As a visiting nurse, Nancy Milio observed at firsthand the horrifying conditions in the Detroit ghetto and became convinced that she and other professionals could help the poor. She assumed that government funds could be raised for a community health program. She expected the Visiting Nurses Association (which had expressed an interest in some of her ideas on community medicine) to help her, and the police and public health authorities to cooperate. She also believed that the people in the community would be grateful for her time and energy.

When I started 9226 Kercheval I felt I could write the rest of the script. A proposal is written; a community board with little power is formed; a modest program with a few young professionals begins and continues for a year or two, after which the professionals leave for more powerful and attractive jobs, but the local residents never gain control of the program. A report is submitted, another experiment with the poor is written off as a failure, and a legacy of bitterness is left behind which merges with the anger and hopelessness that characterize lives in the ghetto.

That was the story I expected 9226 Kercheval to tell. But Nancy Milio seems unlike most people who set up programs in other people’s neighborhoods and then leave after a few years, for throughout her book one is made aware of her own education by the black people she worked with. Her project, the Mom and Tots Center, was initially designed to provide prenatal care for community women, but it was transformed into something very different. For example, the center wanted to hire neighborhood women, but they had no one to care for their young children. Although the project was prohibited by the terms of its grant of funds from caring for children, Miss Milio nevertheless helped to create day care facilities at the center. Young kids from the neighborhood dropped in, but instead of kicking them out, which would have separated the center from the community, she started a group for them. She was supposed to limit her work to prenatal care but she set up programs for baby care and family planning as well, doing what the people near the center wanted instead of acceding to the advice of professionals or the constraints of government financing.

The book shows, as Nancy Milio illustrates in her work,

…first, that health, as a quality of life…must be mirrored in the process of undertaking to improve health. And that those who would involve others, especially the poor, in the process of healthful change, must themselves be involved: the one who would change others must himself be changed.

The subtitle of 9226 Kercheval is “The Storefront That Did Not Burn,” and the publishers make much of the fact that the Mom and Tots Center was not destroyed during the Detroit riots of 1968. That is not surprising, for such projects are more often destroyed by their sources of funds than by the people who live near them. Miss Milio writes:

It was a painful irony to know that at the very moment that Mom and Tots was going on record in the Congress as a successful OEO (poverty) program, the funds for its survival were being withdrawn by OEO.

Nancy Milio and her local staff learned how to write proposals, administer money, and still have the flexibility that is essential to keep up with the rising demands of the community. They set up medical services for the poor while teaching them to care for themselves so that they could eventually take over these services. The center attempted to free the community from dependence upon agencies and professionals from outside. After two years, Miss Milio left, turning the center over to people from the neighborhood, which is unusual, for few people are able to give up power in the interest of the people they are trying to help, or to trust them enough to do so. What had begun as an experiment in community health had to go beyond the experimental stage to survive. Miss Milio’s parting gift to the people she came to know is this moving and useful book about the center, one of the few positive examples of how local power and a more humane environment can grow.

9226 Kercheval was written in 1969 and describes events that happened between 1966 and 1968, when Nancy Milio left. The Mom and Tots Center is still at 9226 Kercheval Street, and although Nancy Milio is no longer directly involved in the center, she is still close to the community, as I was told when I recently spoke to people at the center. Each year the community has had to battle for the center to survive but so far it is doing so. Services have been expanded and the center now provides many different kinds of medical care: home visits by doctors, nurses, and community health workers; day and prenatal care; family planning. The baby clinic still exists as does the club for boys and girls. Some of the children who had been cared for from birth to five at the center will be leaving its nursery school for public school next year.

Advertisement

This prospect is grim, for the Detroit public schools, like most other inner city schools, are very different indeed from the center and are especially damaging to poor children. After a few years most of these children end up with a sense that they will never learn to read or write or know anything the teachers want them to know; they become convinced that they are failures. So it is not surprising that a fight for community control of the schools is beginning in the neighborhood of the center.

It is far from clear how the battle will end. Just as the public schools can undo the work of the center, the police and health and building departments, not to mention the unions, can harass the center and any local educational projects that grow from it if they become too threatening to the power of city politicians and bureaucrats. Programs like the center, therefore, will probably not be free to continue their work until communities have more control of all the public services that they need to survive.

But to define what community means in the cities is very difficult. Communities of interest exist there that are often not geographic. Most communal lives are not bound to place, but are often related to work or profession or education. For example, when I was living in New York, my friends were living throughout Manhattan, whereas the people who lived in my neighborhood were strangers to me. Our schools were controlled by the central bureaucracy, our streets policed by an outside force, and our health needs uncared for. We did not feel we had to know one another or had to battle to define how we wanted our community to be governed. We left that to the central authorities.

Ghetto neighborhoods, where there is less mobility, have perhaps a greater sense of community, but one has no greater control over one’s life in them. Occasionally, programs like the center or like the schools in the I.S. 201 complex or in Ocean Hill-Brownsville develop a budding sense of power, but they usually cannot develop an organization strong enough to mobilize the energies in the community. Community schools battle each other; the health people battle with the welfare department, which battles with the schools. There is competition among the schools themselves and a central authority maintains control. In most communities no larger view of how to gain more power seems to obtain.

Milton Kotler in Neighborhood Government provides the only comprehensive plan for seizing and maintaining local power that I have yet seen. He doesn’t use the word community much (nor does Nancy Milio, who talks about the “neighborhood” rather than the community and means by it the people who live in the ten or twelve square blocks around the center). By using the term neighborhood Kotler avoids having to define local communities of interest. The first point Kotler makes, and it is a useful one, is that battles for control should be territorial ones. He feels that what is needed is neighborhood governance of all the publicly supported services that affect the lives of people locally.

Kotler defines a neighborhood as “a political settlement of small territory and familiar association whose absolute property is its capacity for deliberate democracy.” He does not define a community as an association bound by common interest or common culture. He does not take up the question of creating a community of common political or professional concern, or even of social preference. Nor does he focus on particular institutions such as the schools or the police. The issue for him is political control of territory: the governing of that territory by its residents. According to Kotler self-government, which is to be achieved through a community corporation, “will cover the same areas as those of any government—namely finance, imports and exports, war and peace, territorial defense, and laws.” This is not only abstract but evades the question of control of economic forces, including real estate, business, and services like gas, electricity, telephone, and public transportation whose nature it is to extend beyond neighborhood boundaries. Perhaps he would suggest a “user-controlled corporation” that cut across neighborhood boundaries for the governance of large-scale public utilities.

However it is not clear what Kotler thinks about the control of the economic resources in the community. In his book he says, “Having government authority is more fundamental to changing social institutions than having a vital economic role,” and he passes over the question of the economics of the community, except when he considers publicly governed resources like schools, sanitation, and the police. In this respect interesting questions arise. For example, what is the possibility of a functioning community government extending its control to the economic life of the community and setting up regulations for profit taking and for the public ownership of business? Is a “socialistic neighborhood” conceivable in a capitalist society? Small communistic communities such as those of the Shakers and Mennonites have been able to regulate themselves, but they are far from the Bronx.

Advertisement

Kotler’s advocacy of neighborhood government is not without historical basis. In the beginning of his book he traces the growth of cities through the domination by one small incorporated township of others by means of annexation and disenfranchisement. He also shows how centralized power grew as a powerful township gradually increased its territory with the help of business and often with the active collaboration of state government. Examples of this growth are all around us in the names of the incorporated townships that still designate sections of many cities. In New York the names Harlem, Bedford, East New York, Ocean Hill, Brownsville, Morrisiana, Pelham, Corona all come to mind. In Los Angeles, Watts; in Oakland an annexed community called Brooklyn. In Berkeley the same centralized control developed. The powerful and rich university township of Berkeley annexed the poorer working-class community of Ocean View, whose town hall and police department are still standing, though unused.

In the Bay Area there are some small communities that were not incorporated into larger cities. Emeryville, for example, is a small town between Oakland and Berkeley set up by businessmen as an industrial haven with low taxes to avoid the domination of its larger neighbors. Kensington, a small unincorporated tract north of Berkeley, is a refuge for rich people who control much of Berkeley but want to avoid the taxes and the domination of the centralized government. Finally, the unincorporated town of East Palo Alto (also known as Nairobi), across the freeway from Palo Alto, is a poor and predominantly black community. Most of the people living there work in service jobs at Stanford University or in the rich Palo Alto township which has refused to incorporate East Palo Alto because it is considered an expensive burden. Therefore East Palo Alto does not have local police, sanitation, public works, or schools, and has to depend on the county for all of these services. The city of Palo Alto in refusing to annex East Palo Alto was acting in the same imperial manner as when it attempted to incorporate the rich campus of Stanford University.

However there is no inherent reason for East Palo Alto to want to be annexed, and in fact a movement toward incorporation is beginning there. During the last election a referendum was on the ballot in East Palo Alto to change the name of the community to Nairobi as a gesture of independence from the richer Palo Alto community. The referendum and the movement toward independent incorporation were defeated, though the battle is not yet over.

The problem in East Palo Alto as in many other poor communities is that to incorporate and control the government and to receive state and federal money require a high degree of organization as well as legal competence; while it is precisely poor communities that lack organization and qualified professionals who are willing to serve rather than exploit others. Kotler’s book contains the paradox that in our society the people most likely to benefit from his ideas are those least likely to have the power to carry them out.

Kotler describes what a neighborhood is:

The most sensible way to locate the neighborhood is to ask people where it is, for people spend much time fixing its boundaries. Gangs mark its turf. Old people watch for its new faces. Children figure out safe routes to home and school. People walk their dogs through their neighborhood, but rarely beyond it. Above all, the neighborhood has a name.

Neighborhoods, he finds, range in size from half a square mile to six square miles, and from 2,500 people to 75,000 people (although the latter figure makes me wonder about that community’s capacity for deliberative democracy). There are new neighborhoods, however, that have no names, that is, the student and “street people” communities that have developed in many cities and university towns. Some of these are beginning to show signs of stability, now that many former students instead of moving away from Berkeley, Madison, Cambridge, and Isla Vista are settling there. Although Kotler’s analysis is primarily aimed at developing a strategy for the acquisition of power by the poor, it equally applies to the newer neighborhoods of the hip.

The struggle for control of the neighborhood can begin, according to Kotler, with the creation of a community corporation (the book gives examples of several that already exist) whose members—all residents of the community meeting minimal requirements can be given membership—claim power over the public money coming into the neighborhood. This claim to political power over the use of taxes and the allocation of resources and services within the neighborhood can both generate discussion about what should be done and mobilize people to demand from the city and state the transfer of authority from centralized bodies back to the neighborhood. Something like this has taken place recently in control of education and the police of some communities, but a comprehensive plan for control as advocated by Kotler has hardly emerged. Yet, as Kotler says, the cities now don’t really control the neighborhoods, especially neighborhoods that are poor or black or hip. Perhaps he is right in claiming that the American city is “a floundering empire, no longer in control of the neighborhoods it has annexed.”

The development of a community corporation, “the legal incorporation of the local territory and the writing of a formal constitution of internal rule,” can come from any one of a number of already functioning organizations: from a community health program like the center on Kercheval Street, from a school or a local welfare rights group or a food conspiracy or rent strike committee. When a group needs to move beyond its own immediate province and is ready to start thinking about local control, it is ripe for incorporation and the struggle to seize power from centralized authority.

I think that Kotler is right in emphasizing neighborhood and territory instead of community of interest. Democratic participation certainly needs diversity and disagreement to develop, and it probably works best when the people making the decisions share the same piece of territory. Berkeley is worth mentioning in this respect. The recent elections put three radicals on the city council who, in spite of their political differences, agreed on the importance of the allocation of resources in Berkeley. The budget has recently been reviewed closely in hearings that seemed endless and were often tedious. But since each allocation was publicly scrutinized, for the first time anyone in the city who wanted to had a chance to challenge budget items and propose new ones. In fact more people came to address the council than had ever done before. There were long hearings on medical zoning, women’s rights, rents, hiring policies, the police budget, the public utilities.

Changes are emerging. After a long battle the conservative city manager and several other bureaucrats have resigned. A number of programs including neighborhood-based drug treatment centers and a center for rape victims have been given city funds. A commission to rewrite the city charter has been formed and it is likely that the city manager style of government will be changed in the next four years. There is serious talk about the establishment of neighborhood medical and day care facilities. At the moment there is a feeling in Berkeley that some degree of local control is possible, and many people who felt helpless and excluded in the past are willing to work on small but important changes.

This is still far from the neighborhood control advocated by Kotler. Berkeley has several neighborhoods with different interests and the city may yet be broken down into a group of federated neighborhoods with a central council. This is analogous to what Kotler envisages for America—a group of federated cities with no centralized control but with sanction from the state and with representation in the state legislature.

It is important to distinguish what Kotler is talking about from the centrally imposed decentralization that was current in educational circles several years ago. Mario Fantini, Marilyn Gittell, and Richard Magat in their book Community Control and the Urban School* give an account of the Bundy report on decentralization of the New York City schools in which they advocate a mild form of community involvement in the schools. Yet in summarizing the suggestions of the Bundy Commission, they reveal clearly the centralized nature of the so-called school decentralization plan:

- The New York City public schools should be reorganized into a community school system, consisting of a federation of largely autonomous school districts and a central education agency.

- From thirty to no more than sixty community school districts should be created, ranging in size from about 12,000 to 40,000 pupils—each district large enough to offer a full range of educational services yet small enough to maintain proximity to community needs and to promote diversity and administrative flexibility….

- A central education agency, together with a superintendent of schools and his staff, should have operating responsibility for special educational functions and citywide educational policies. It should also provide certain centralized services to the community school districts and other services, upon the districts’ request.

The state commissioner of education and the city’s central educational agency should retain their responsibilities for the maintenance of educational standards in all public schools in the city….

The central educational agency should consist of one of the following: (a) a commission of three full-time members appointed by the mayor or (b) a board of education with a majority of members nominated by the community school districts. In the latter, the mayor should select the members from a list submitted by an assembly of chairmen of community school boards; the others should be chosen by the mayor from nominations made by a screening panel.

The community is accountable to the central authority, which sets educational standards. Overriding principles need not emerge from the community and might be against its will. Moreover, the districts will be created by the central authority, not necessarily with regard to the neighborhoods in which people live. I have found that attempts at legislating decentralization or mandating change are self-defeating. Local power has no time to grow on its own; only “responsible” people, i.e., those trusted by the people already in power, are included in the plan. There is little chance for participation to develop on a broad scale or for the community to fight out its own internal disagreements in a public forum, define its own needs, and develop leaders it can trust. The growth of the community as a political unit with all its diversity and conflict will not happen when power is imposed or permitted too easily by a liberal though cautious central authority. For if the community steps out of line or fails to meet liberal expectations, the money and power will be withdrawn. The community cannot maintain its power when it lets itself become dependent upon official permission to act.

A group of schools in Berkeley (including one which I started and where I taught for three years) fought to establish the idea that parents, students, and teachers who want to make a school should be supported by public money but should also retain the right to determine the school’s curriculum and goals as well as control its facilities. Several schools managed to grow over the last three years, none with all the public money needed but at least with enough public money to survive.

Last year we received a visit from the Federal Curse. The superintendent in Berkeley applied to the Federal Government Experimental Schools Program for a grant to develop alternative schools throughout the Berkeley public school system. The school administration, which had before been opposed to both local control and alternative education, received a $3.2 million grant. The people involved in the existing alternative schools were not allowed to take part in the negotiations for this federal grant or to write the proposal. Suddenly almost everyone in the public schools was willing to call his school an “alternative school” and come out for local participation (not control, of course) to get some of the money.

While our opponents adopted our rhetoric, the district had to create a bureaucracy to administer the funds. We now have a “Director of Alternative Schools,” two assistant directors, a public relations office, several evaluation teams, a media team, a staff of secretaries and typists—and our own schools are as poor as ever. The money is now in “responsible” hands. Some of us wish the money had never been granted. It does nothing to improve the lives of the young or the powerless.

A program has to be strong both internally and politically in order to fight the power of existing bureaucracies to absorb money. Power has to grow within the community before outside money can be used effectively, and, in fact, if local power develops outside money may not be so necessary. The idea that an infusion of money tied to supposedly liberal ideas will enable people to gain greater control is naïve. People have to get power for themselves and then use whatever money and facilities they can manage to find, whether they get them by demanding their share of local taxes, by obtaining unrestricted government funds, or from contributions from foundations and from local churches, stores, and residents.

Kotler’s idea of neighborhood government seems remote at this time. As I mentioned before, poor communities tend to be demoralized in the first place. Moreover, it is hard to estimate the nature and the intensity of the opposition that might emerge if redistribution of power seemed imminent. Not only must the existing centralized authority be dealt with but all of the interests that it protects. There are old machine politicians, landlords who feel protected by the corrupt central city, businesses that are immune from effective regulation, incompetent public service workers, unions of teachers and social workers and others whose profession it is to serve the poor. One got an inkling of the hostility and the bitterness that can emerge during the struggles over Ocean Hill and IS 201; and these battles were limited only to the schools.

Individuals who dare to organize communities will be under constant pressure and will have to plan a struggle of years and not months. It is hard to sustain this if one is poor or powerless. When we tried to control the schools in Berkeley I had the feeling that no matter how threatening we became the established bureaucracy would simply wait for us to run out of steam or to wipe ourselves out, and then they would move back in. In fact, most of us were wiped out and the bureaucracy is moving back. We learned how right Kotler is in arguing that people will obtain control over their communities only by claiming and fighting for the right to that control—and also how far we, and others with similar concerns, were from taking real power.

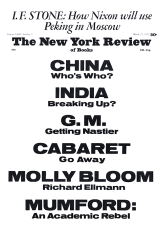

This Issue

March 23, 1972

-

*

Praeger, 288 pp., $9.00; $3.50 (paper). ↩