She has a strange relationship with DiMaggio—strange because it cannot possibly be as mundane as she will later present it—and it is virtually undocumented, although choking in factoids. DiMaggio never gives much to an interview, and her version of him, when married to Arthur Miller, is spiteful, even reminiscent of the way she has already dismissed Jim Dougherty, her first husband. Yet DiMaggio will always be there when she needs him, and is probably her closest friend in the months before she dies. Certainly he is the first of the bereaved at her funeral. The enigma that remains is that of their sex life. Was it a marriage whose good humor depended on the speed with which they could make love one more time, and lie around in the intervals suffering every boredom of two people who had no cheerful insight into the workings of the other’s mind; or is it a failure of tenderness (and soon a war of egos monumentally spoiled) between an Italian man and an Irish girl (by way of Hogan) who had been built to mate with one another, and would therefore have been able to thrive in any working-class world where marriage was designed for cohabitation rather than companionship.

These speculations belong to gossip unless we recognize that if it has not been sexual attraction, or some species of natural suitability, that brings them together, then her motivation is more than a little suspicious, and even suggests she has grown ruthless in the years since Ana Lower’s death. While accounts of their first date excite a factoidal rhetoric with only the smallest resonance of reality—“There’s a blue polka dot exactly in the middle of your tie knot. Did it take you long to fix it like that?” she is supposed to say after a silent dinner, while he is supposed to blush in silence and shake his head—still the tempo of their subsequent meetings takes on acceleration in proportion to her recognition of his fame.

She knows nothing about ballplayers when she meets him—she might as well be the belle of Puerto Rico being introduced to Stein Eriksen—she is merely relieved, she confesses, that he did not have “slick black hair and wear flashy clothes.” Instead he was “conservative, like a bank vice-president or something.” (To someone as protean as herself, dignity would be indispensable in a man, a node of reference by which to measure her own spectrum of movie star manners, good and bad.) It is only over the next few weeks that she comes to learn he has been the greatest baseball player of his time, the largest legend in New York since Babe Ruth. With her capacity to measure status—she has passed already in her life from microcosmos of the social world into macrocosmos, there is not too much a headwaiter need do before she can detect by the light in his eye that he is feeling the unique and luminous spinelessness of a peasant before a king. She is on a date with an American king—her first. (The others have been merely Hollywood kings.)

On the movie sets, as items appear in the gossip columns about whom she is dating, the stagehands and grips are more cordial than ever before. Proud and scornful hierarchy of the working class, tough, cynical, contemptuous, and skilled, they have never as a collective group been remotely as friendly before. That opens her domain. She has already risen from freak to secret nude of the national dreamlife. Now she can rise again, be queen of the working class. For DiMaggio’s wife is beyond reproach. When he comes to visit her on the set of Moneky Business, a picture is taken of Cary Grant and himself with Marilyn between. When the photo is printed in the papers, Cary has been cut out of the photograph. The publicity department at Twentieth is announcing the public romance of the decade. Down in Washington, ambitious young men like Jack Kennedy are gnashing their teeth. “Why is it,” they will never be heard to cry aloud, “that hard-working young Senators get less national attention than movie starlets?”

Within the studio, there must be grudging recognition at last that they have some sort of genius on their hands. She is not only going to survive her own millions of calendar nudes but will sell tickets to her films right off those barber shop and barroom walls. Every time a man buys gas at a filling station and goes in to wash his hands, her torso will be up next to the men’s room door. Soon the story of her mother will come out and fail to hurt her—the public is too interested in the progress of romance with DiMaggio to wish to lose her. And she plays the situation with all the aplomb of a New York Yankee. For the longest period she will refuse to admit they are more than “friends.” No denial is more calculated to keep a rumor alive. There is even the possibility that her interest in DiMaggio begins right out of her need to play counterpoint in public relations. Mosby’s wire-service story on the nude calendar has gone out on March 13, 1952, and Zolotow has her witnessing her first baseball game on March 17 when DiMaggio is playing in some special exhibition (since he is now retired), an event which would therefore have to take place almost immediately after their first meeting, although Guiles, whose chronology is more dependable, does not have them introduced until April. Either way, the supposition reinforces itself that she certainly had a good practical motive for continuing to see DiMaggio.

Advertisement

His relation to her is obviously simpler to comprehend. If it is necessary to speak of her varieties of beauty, then a thousand photographs are not worth a word. Doubtless she is, when alone with him, nothing less than the metamorphosis of a woman in one night, tough in one hour and sensitive in another (at the least!), but she has also the quality she will never lose, never altogether, a species of vulnerability that all who love her will try to describe, a stillness in the center of her mood, an animal’s calm at the heart of shyness, as if her fate is trapped like a tethered deer. At her best, she has to be utterly unlike other women to him, eminently more in need of protection, for she is so simple as to live without a psychic skin.

If at this point her personality seems to have bubbled up into the effervescence of a style that will present her in one paragraph as wholly calculating only to offer next a lyric to her helplessness (of which the best glimpses have been caught in old newsreels), the answer is both, yes, both are true, and always both, she is the whole and double soul of every human alive. It is, if we would search for a model, as if an ambitious and sexual woman might not only be analogous in her particular ego and unconscious life to Madame Bovary, let us say, but rather is a woman with two personalities, each as complex and inconsistent as an individual.

This woman, then, is better seen as Madame Bovary and Nana all in one, both in one, each with her own separate unconscious. Of course, that is a personality which is not seriously divided. One unconscious could almost serve for Nana and Bovary both. It is when Nana and Joan of Arc exist in the same flesh, or Boris Karloff and Bing Crosby, that the abysses of insanity are under the fog at every turn. And there is Monroe with pictures of Eleanora Duse and Abraham Lincoln on her wall, double Monroe, one hard and calculating computer of a cold and ambitious cunt (no other English word is near) and that other tender animal, an angel, a doe at large in blond and lovely human form. Anyone else, man or woman, who contained such opposite personalities within his body would be ferociously mad. It is her transcendence of these opposites into a movie star that is her triumph (even as the work she does will eventually be our pleasure), but how transcendent must be her need for a man ready to offer devotion and services to both the angel and the computer. How large a requirement for DiMaggio to fill. The retired hero of early high purpose too early fulfilled, he is now a legend without purpose. Yet he is not forty and adulation is open to him from everyone. How natural to look for a love where he can serve.

Of course, he is a hint too vain for the prescription. Somewhat further along in their affair, when Marilyn is making Niagara and is high on the elation that she has been given the lead in Gentlemen Prefer Blondes, they spend a few days together in New York. Zolotow gives a good description of their social differences:

At Shor’s, Joe’s friends sat with him and talked about the 1952 pennant races. She was bored. She wanted to see the new plays. She wanted to go to the Metropolitan Museum and to visit the hot jazz spots, like Eddie Condon’s. Joe didn’t care for theater, music, art. His world was the world of sports, his cronies were sports-loving men like George Solotaire, men who lived in a closed masculine world of gin rummy, sports, betting, money talk, inside jokes.

That is a world which can take on dimensions of risk in Hemingway, or pathos in Paddy Chayefsky’s Marty. It is also a world where women can be mothers, sisters, angels, broads, good sports, sweethearts, bitches, trouble, or dynamite, but are always seen at a remove, as a class apart. It is a world of men whose fundamental habit is to live with one another and compete with one another. Their habit is not homosexual but fundamental. Its root is often so simple as having grown up in a family of brothers, or known more happiness with their father than their mother—the days of their lives have been spent with other men. Women are an emotional luxury. Of course, like all luxuries they can be alternately ignored and coveted, but it is false to the whole notion of that world, and impossible to understand DiMaggio, if it is not seen that the highest prize in a world of men is the most beautiful woman available on your arm and living there in her heart loyal to you. Sexual prowess is more revered than any athletic ability but a good straight right. It is precisely because women are strange and difficult, and not at all easy, that they are respected enormously as trophies.

Advertisement

It is part of the implicit comedy of DiMaggio’s relations with Monroe that he would expect her to understand this. There is a story of a very tough man, told in New York bars, who revered his wife and lived with her for twenty years, and at the end of that time she said, “Why don’t you ever tell me you love me?” He grunted and said, “I’m with you, ain’t I?” Women who can live with such men obviously have to comprehend their code. It is as if DiMaggio expects her to understand, with of course never a word being said, that he has not arrived at his eminence in Toots Shor’s along with Hemingway and one or two select sports writers and gamblers because he is dumb or gifted or lucky but because he had an art that demanded huge concentration, and the consistent courage over the years to face into thousands of fast balls any of which could kill or cripple him if he were struck in the head, and closer than such danger, engage his ego in the perilous business of each working day being booed or cheered depending on how he passed the daily test of pressure.

If he had been a New York Yankee, and therefore in the highest part of that sporting establishment honored by the corporation, the diocese, and the country club; if DiMaggio with his conservative clothes and distinguished gray hair was a considerable distance from the athlete who gets up in the morning with his head axed by a hangover and blows his nose to get the sexual gunk of the night before out of his nostril hairs (which act excites him to give no farewell kiss to the garlic and bourbon breath of the sleeping sweaty broad of the night before), then stumbles out in white shirt and tie into early morning sunlight to take his place at a communion breakfast, and get up on his feet in his turn with other ballplayers and prizefighters to tell the parochial kids how to live, cleanly, that is, as Americans; if DiMaggio has too much class to be part of this hogpen of whole hypocrisy (he is a Yankee and the best), still he has all the patriotism, all the punctilious social behavior that are still required of great athletes in the early Fifties: his propriety has to reinforce the romantic image he must hold of himself and his love for her. His communion to her, his gift to her, is that he loves her. He’s there, isn’t he? He will certainly be her champion in any emergency. He will die for her if it comes to that. He will found a dynasty with her if she desires it, but he does not see their love as a tender wading pool of shared interests and tasting each other’s concoctions in the kitchen.

He is, in fact, even more used to the center of attention that she is, and probably has as much absorption in his own body, for it has been his instrument just so much as her anatomy has become her instrument, and besides, the body of a professional athlete is part of the capital of a team, and numbers of trainers have spent years catering to it. Indeed, the one of her associates he likes the most is Whitey Snyder, her makeup man, who looks like a cross between Mickey Spillane and a third-base coach. DiMaggio can understand and get along with the man who helps her to keep her professionalism in shape. The easiest thing he can understand in her world is Synder talking about how he does her face: “Marilyn has makeup tricks that nobody else has and nobody knows. Some of them she won’t tell me. She has discovered them herself. She has certain ways of lining and shadowing her eyes that no other actress can do. She puts on a special kind of lipstick; it’s a secret blend of three different shades. I get that moist look on her lips for when she’s going to do a sexy scene by first putting on the lipstick and then putting a gloss over the lipstick. The gloss is a secret formula of vaseline and wax….” It is like listening to a trainer hint at the undisclosed blends of a superliniment, or an athlete describe how he bandages himself, but, finally, DiMaggio cannot have the same respect for movie people that he has had for athletes who pass tests. He has discovered the wheel. They are people with false identity. Phony.

And she has to be suffering all the anguish of living with a man who will save her in a shipwreck or learn to drive a dog team to the North Pole (if her plane should crash there) but sits around the apartment watching television all night, hardly talks to her, is not splendidly appreciative of her cooking and resentful when they go out to restaurants, acts like a maiden aunt when she gets ready to go out in the world with a swatch of bare bosom, and, incredible pressure upon her brain, wishes to end her movie career! She needs, ah, she needs a lot. No heroic man of hard-forged and iron identity (with both his souls wed into narrowminded strictures and athletic grace), no, she needs a double soul a little more like her own, a computer with circuits larger than her own, and a devil with charm in the guise of an angel, something of that sort she certainly needs, but wholly devoted to her. Because the keel of her identity has at last been laid—she is her career, and her career is herself. No lover can shift this truth—as quickly let a wife ask Thomas Alva Edison to abjure his laboratory! She will never get what she needs in the full proportion of her needs—never enough creative service to satisfy taste and tender wit—a man who can anticipate that if she claims to love anemones they must still not be too violet, a slave of exquisite sweetness who will foresee appetites and develop them by art and surprise, someone who—full lament of a woman—someone who will bring her out! Instead she has DiMag, worth the front page of the New York Daily News every time he smiles. DIMAG SMILES!

So their affair goes on, they fight, have reconciliations, fight again. They separate, and they love each other more on the phone. He will be in New York and she will make a film. He will come to San Francisco and she will go to New York. They reunite in Los Angeles, or she goes to visit his restaurant at Fisherman’s Wharf. They surreptitiously move clothes into each other’s apartments—then tell the newspaper world they are still only friends. For near to two years it goes on. He wishes to marry, but she is uncertain, then he will go away for a few weeks in disgust, or refuse to accompany her to a function where she most certainly wants him along. On one night in 1953 when she is given a Photoplay magazine award, DiMaggio is so outraged by the cut of her dress that Sidney Skolsky has to take her to the dinner. Joan Crawford will be equally censorious: “Sex plays a tremendously important part in every person’s life,” are her words to columnist Bob Thomas. “People are interested in it, intrigued with it. But they don’t like to see it flaunted in their faces. She [Miss Monroe] should be told that the public likes provocative feminine personalities; but it also likes to know that underneath it all, the actresses are ladies.”

Is this the voice of DiMaggio in Miss Crawford’s mouth? “I think the thing that hit me the hardest,” said Marilyn, now offering an exclusive reply to Louella Parsons, “is that it came from her. I’ve always admired her for being such a wonderful mother—for taking four children and giving them a fine home. Who, better than I, know what it means to homeless little ones?”

She is also shaming DiMaggio. He, too, is being cruel to the homeless little one. Yet is it possible he is the one responsible for the fact that she has never been more attractive than in these years? She looks fed on sexual candy. Never again in her career will she look so sexually perfect as in 1953 making Gentlemen Prefer Blondes, no, never—if we are to examine a verb through its adverb—will she appear so fucky again. It is either a reflection of her success at the studio, or the secret of her sex with DiMaggio, and that is one secret she is not about to admit. She will look more subtle in future years, more adorable, certainly lovelier, more sensitive, more luminous, more tender, more of a heroine, less of a slut—but never again will she seem so close to a detumescent body ready to roll right over the edge of the world and drop your body down a chute of pillows and honey. If all this kundalini is being sent out to an anonymous human sea, her sex flowing forever on a one-way canal to the lens and never to one man, it is the most vivid abuse of kundalini in the history of the West, and makes her indeed a freak of too monumental proportions. It is easier to comprehend her as a woman often void of sex in the chills and concentration of her career, but finally a woman who has something of real sexual experience with her men, for she tends to take on the inner character of the lover she is with, something of his expression.

In the best years with DiMaggio, her physical coordination is never more vigorous and athletically quick; she dances with all the grace she is ever going to need when doing Gentlemen Prefer Blondes, all the grace and all the bazazz—she is a musical comedy star with panache! Diamonds Are a Girl’s Best Friend! What a surprise! And sings so well Zanuck will first believe her voice was dubbed, and then will finally go through the reappraisal, ulcerous to the eye of his stomach, of deciding she may be the biggest star they have at Twentieth, and the biggest they are going to have. Yes, she is physically resplendent, and yet her face in these years shows more of vacuity and low cunning than it is likely to show again—she is in part the face DiMaggio has been leaving in her womb. “Take the money,” he says to her on one occasion when she is talking about her publicity, and something as hard and blank as a New York Yankee out for a share of the spoils is now in her expression.

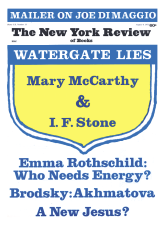

This Issue

August 9, 1973