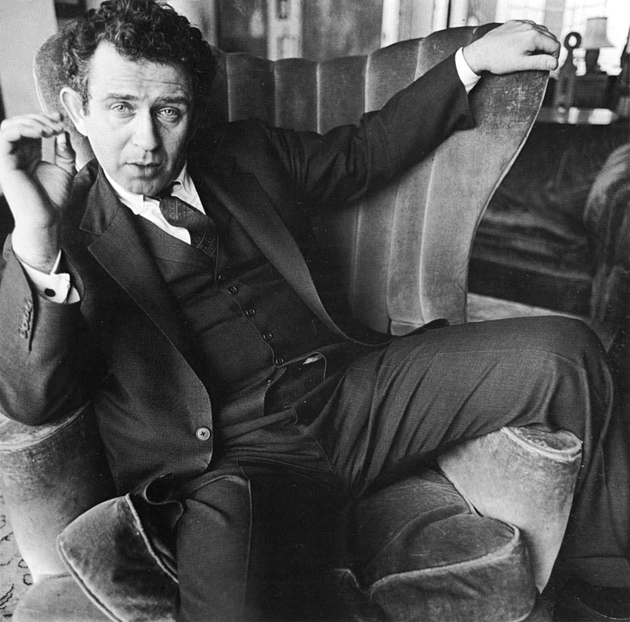

We publish here the second of three selections from the letters of Norman Mailer, with notes provided by Michael Lennon. These letters, written while Mailer was working on his novel The Deer Park or just after he finished it, are addressed to three novelists he was close to at the time, William Styron, Vance Bourjaily, and James Jones. All the letters are in the collection of the Harry Ransom Center at the University of Texas at Austin.

—The Editors

To William Styron1

February 26, 1953

Dear Bill,

You certainly deserve a fan letter. As a matter of fact I’ve been meaning to write ever since I read “Long March” about a month ago. I think it’s just terrific, how good I’m almost embarrassed to say, but as a modest estimate it’s certainly as good an eighty pages as any American has written since the war, and really I think it’s much more than that. You watch. It’s going to last and last and last. And some day people will consider it as being close to the level of something as marvelous as The Heart of Darkness, which by the way, for no reason I know, it reminded me of.

Barbara mentioned that you’re without a book at the moment. No solace I can offer, except that crap about waiting and patience which is all true, but no consolation at all.

I have only one humble criticism. I wonder if you realize how good you are. That tendency in you to invert your story and manner your prose just slightly, struck me—forgive the presumption—as coming possibly from a certain covert doubt of your strengths as a writer, and you’re too good to doubt yourself. Which I suppose is like saying, “You, neurotic—stop being neurotic!”

Anyway, I did want to write you these few things.

My best to you, Bill,

Norman

To William Styron

April 24, 1953

Dear Bill,

…I’ve come to one of those idiot decisions we all make I suppose now and again; floundering in my second draft, writing that precious first chapter over and over for what has now been a month. I’ve come to the conclusion since the results don’t warrant the work, that I’ve been p1aying games, and so starting Monday I’m going to try to blast this little old book. I’m going to write every day, and like Lot’s Wife I’m consigning myself to a pillar of salt if I dare to look back. Maybe after a hundred pages of the blitz I’ll find the book and it’ll get better and then I can go back and rewrite. It’s the way I did Naked, and the measure of my present sad state of morals is exactly that I look to the past for cues on how to handle the future. Anyway, today is letter-writing day in preparation for the big sprawl.

I got a big boot out of your letter. Not only for the compliments although I was truly pleased, but just I suppose because you felt like talking about those things with me. I think I probably agree with most of what you said, there’s really no need to tote it up item by item, although, I hope I didn’t give you the feeling that I thought you should write simple pound-pound stuff. The thing about The Long March (I still haven’t read Lie Down in Darkness2 mainly because I haven’t dared to with my own book in such sad shape—it would be too depressing) is that kind of extraordinary long narrative breath you have which really, I think, when you hit full stride and full power—do you want it at thirty or forty?—will have a certain majesty to it. As I get a little older I can accept things in other writers which I don’t have, and I think I could accept them a little faster if my own stuff would grow. I suppose this is all by way of preface to saying that we each approach our own work in very very different ways, and that when I wrote that I didn’t want to be “presumptuous” and then mentioned your “mannerisms,” I did it with no sense that I could show you what to do, but on the contrary admired the work so directly, including your full styles, that I just wanted it to be even better. This is getting to be a Mutual Admiration Society. Indeed, indeed.

At the moment what’s killing me in my work is that dilemma of point of view. I find that when I write in third person I’m so bound, so constipated, that I can’t seem to enter people’s heads—I write as if the damn thing were a play, scene, dialogue, entrance, exit, and of course it’s very wasteful. It takes forever to get to the point that way. First person is even worse. The moment I have a character in first person, I tighten up, my narrator becomes a stiff, haughty, cold young man whose relation to myself I’ve never been able to discover.

Advertisement

In a way I think I understand why. To write well in the third person, to be omniscient, one has to have a life-view, and if one is a serious writer, it has to be a life-view of some depth and some capacity for embracing entities, contradictory people, etc. etc. The thing which is so bad about the average third person novel is that the matter, the interpretation, is absolutely without life-view, it’s written the way everyone else sees it, and that irritating maddening business of pop, pop, pop, in and out of the minds we go, comes because there’s no mind directing it. I think that’s why writers like Maugham as they shrivel turn so naturally to the first person narrator—it’s the perfect substitute for a life-view. One’s form is given by the sole perceiver, although unhappily it’s the exact opposite of the expansive life-view of the major novelist. And it’s so binding as well. Anyway, these days, trying by an act of will (which I don’t disapprove of entirely) de me meler dans le monde [to be out in the world], I find that I actually sweat from the fear of getting loose in such a book and revealing my fundamental poverty of imagination, and so for this first month, I’ve been rushing virtually on alternate days from third person to first person and back again, disgusted in first person by the artificial barriers I set up on a book which shouldn’t have them. Do you ever suffer from this kind of thing?

Your invitation to meet you in Ravello had me drooling for a moment. But I don’t dare go right now. Maybe next winter for skiing. Will you still be there then? Once in a great while I’ll remember Europe with the kind of pang one remembers things like spring in sophomore year at college or that sort of thing. My best to you, Bill, and as you said, let’s write to each other whenever we’re in the mood. Actually, I got in the mood while writing the letter. (Hence my defense of the act of will.)

Yours,

Norm

To William Styron

Mexico

July 24, 1953

Dear Bill,

First of all, a belated congratulations on your marriage.3 There’ve been times in my life when I could not see how possibly one could give an honest set of good wishes for such an impossible institution, but at the moment, things with Adele being very good indeed, and this after two and a half years, I’m feeling optimistic about such matters as life, love, and the relations between men and women. In any case, do say hello from me to your wife whom I shall be delighted to meet whenever we get together again.

Adele and I have gone down to Mexico,4 and at the moment we’re staying at a weird sort of place a couple of miles out of Mexico City called the Turf Club which was built originally as a kind of country club for wealthy Mexicans, became used by them as boffing huts for their mistresses, degenerated into the beer can and fly stage, and is now being just so slightly regenerated. We live in a round little house with a balcony bedroom that is all windows, and there’s a fine view of a canyon and mountains on the other side. Since we had been traveling for six weeks without let-up, we’ve come apart slightly here, and though it’s our hope to work each of us for a couple of good hard months, I’m quite lethargic at the moment.

I wonder if you’ve ever been to Mexico, Bill? I suppose either way there’s no point describing it. I mention it only because I have the feeling that you might find it enormously stimulating. It’s a country of such violence and grandeur too, and its history is so bloody and so close to the tragic at times that I wish I found it more congenial. But I’ve something against the tropics—maybe the Philippines which I disliked the way every soldier dislikes where he is—and so I tend to see this as a place where I’ll not work and just quietly degenerate. How we wrap degeneration around ourselves.

Advertisement

Anyway, it’s very cheap here, and that might be of interest to you. There are towns (Vance [Bourjaily] was in one) where you can rent a pretty good house for $25 a month and under. The depressing thing to me about Mexico, with all its excitement, is of course the poverty. The Northern conscience seems to function best when the inequalities of wealth and poverty are not too glaring. Here, I find in myself two things which are new. The thought of having lots of money is appealing for the first time, and the thought of poverty is distasteful. Ignore it, isolate yourself from it. Gives a kind of insight into the Colonial British and how they could be so dreadful.

I’m at a funny place with my book. I gave up the draft I was pushing in third person, deciding finally that while objectively it might be a better book, I just didn’t have the enthusiasm to write it. And so now I’m back to my first draft which is in a curious shape. I’ve finally been able to see it, and I think all of it which is minor, (minor characters, minor themes, etc) is the best I’ve done, but the heart of the book, which I’ve finally boiled down to a key sixty pages is bad, slovenly, and what have you. So if I can write sixty new pages which are right, I’ve got a book. It’s maddening because if I can find what to do, I’ve got a novel in sixty days or so, and if I can’t, I suppose I can fritter away another year or more. It’s the old business of not knowing just what I want to say—there are so many half-formed things I feel about love and sex and the boundaries and demarcations of them, and other themes too, all very worth-while, but I don’t know where to grasp them, and I’ve got to make up a brand new sixty pages or eighty or whatever they’ll turn out to be. So as we always are before work, I’m scared stiff, especially since I can’t put it off any longer—all the reasons for not working are now gone.

I know so well what you mean by the need to have the sockeroo first page before you can go on, and I don’t know that it’s so bad. I’ve always found it terribly hard to write something better in a second draft than in a first. One’s book is alive in the first draft as it never is again, and to be sloppy with it then is to pollute the whole book. Anyway, luck on your novella. And a passage through it. Sometimes I realize how good we are when I read some of the touted English novelists—like Ford Madox Ford—A Man Could Stand Up5—which has its merits but is so completely a minor book I think.

Adele and I stopped in at James Jones’ colony6 in Marshall, Illinois. If you read the article in Life, you’ve had an objective portrait of it, surprisingly accurate. Actually, the reality is not there, though. Lowney Handy7 and Jones are people whom one can satirize so easily, and yet one’s missed it all, for both of them are such extraordinarily passionate people, that their errors as well as their successes have a kind of grotesque to them. Lowney Handy burns—I kept thinking of fanatics like John Brown when I looked into her eyes. Jones like all of us is having his troubles with the second book, but everything happens to Jonesie on so big a scale that his troubles are flamboyant next to ours, and involve money, movie scripts, gymnastics, obscenities, raw insecurity, triumphant phallicism, and wham, wham, wham, it’s all explosion. With it all, I like him tremendously. I suppose I have the kind of friendship with him that I had when I was a kid with other kids on the block. He’s really worth knowing. I’ve never come across anyone so intelligent and stupid, so penetrating and insensitive all in one.

For the first time in years I have some hope on the world situation. If Russia collapses, ah if Russia collapses which at heart I doubt, then we enter upon a heroic period. I’m serious, Bill. It’ll be the world against the U.S. and as authors we’ll have winebags full of heroes, villains, and poltroons. So let us keep our fingers crossed. Wouldn’t you like to live in a heroic time before it’s too late?

My typewriter salutes yours. (Latin imagery.)

All the best,

Norm

To Vance Bourjaily8

Turf Club, Mexico

September 26, 1953

Dear Vance,

…I’ve had a pretty good summer working here, and the way things look now I’ll be going back with most of a second draft on The Deer Park . There’s still months of work on it, but fear is gone now and I think it’s going to be a good book, maybe my best so far as I see them. So, at the moment, (no guarantees for next week) I’m in a far better general mood than I was in New York. This book has been just murder—to quote Calder [Willingham]9—Gawd I suffered—but after two years plus, I think I’ve finally found it. Which is, Vance, I suppose, the basis of my disagreement with you. Because my experience with all three novels now has been one of starting with characters, finding things for them to do, and then sometimes after I’ve finished as with Naked, or else at the ¾ point as with Barbary and Deer Park, I discover what my damn theme is. And to hell with the theme in a way, for I always know even before I start something what the connected theme is between all the books, the thing which makes us write I suppose, and for me it’s probably never been anything more profound than, “Itch, you bastards, I hope I make you uncomfortable to the death.”

In that sense, perhaps all I write, is political (short stories excepted) and my themes are political. But I have to confess that I drew a blank on the idea that I must reinvigorate the themes of Barbary . You may be right, and the fact that I don’t see it at all, is indication of that, but I can only respond with what I do feel more or less consciously, and the curious thing is that I seem, whether successful or not, to exhaust themes for myself, so that since Naked I’ve had very little interest in war, war fiction, etc. etc., and since Barbary very little in radical fiction and its problems. I’ve sometimes even felt there must be something miserably superficial about me because it all becomes so much part of the past.

And then, who knows how themes inter-relate? The Deer Park is almost obsessed with the whole business of what is sex, what is love, where do they combine, where do they separate, etc. etc., but the funny thing is that in its own way, so far as books have effect, it may end up being more politically exercising—since love and sex must go into morality, and morality into society—than Barbary, which for all I know may have most of its interest years from now, if there is any interest, as an example of novelisticism, and all the unconscious points it makes on what to do, and what not to do in writing fiction work. Anyway, what I’ve tried to say, is that I never start with a theme. I start with a piece of something and have to worry it for years until it becomes at best a little world with its own laws and its own logic for that book. Frankly, Vance, I don’t even like the theme business—I think it belongs to the critics. [John] Aldridge10 with all his considerable merits has the terrible vice of being unable to read a book until he’s tracked down the theme. Once the animal is skinned, I get the feeling he holds it next his nose while he flips the pages, and smells it from time to time to see if he should like what he reads.

The thing about experience and material is something else. Maybe you’re right, probably you’re right—I’ve had the argument with [Jean] Malaquais11 many times—but to me the fact remains that the more the experience the better the chance to come up with something fortunate. I don’t even know quite how, but at its best experience can give you ideas for the other things, so that maybe working as a stevedore for a year might help one to write a novel about priests. There’s something somewhere about the idea of proportion, and seeing everything in its place. Besides, one can go after experience consciously, determinedly, and in a funny way not disqualify oneself for writing about the material.

I went to Hollywood four years ago because in the back of my mind was the idea that I would write a nice big fat collective novel about the whole works—the idea I suppose with which every young writer goes out. What’s happened is that after several years I am writing a Hollywood book, enormously different from the one I saw a priori, a book where the word Hollywood does not occur once, and where the preoccupation is with other things than with Hollywood itself. It’s also true that some of the best scenes are wholly imaginary and have absolutely no relation to my own experience, but I do believe they come out of a body of experience which enables me to feel proportion.

That’s why I envied [Irving] Shulman12 and Kennedy13—although for different reasons each of them. If I had had Shulman’s material I would not have written a book about a “thing” as you put it so well, I would have worked up some sort of world. (I think it can almost be put that one feels the need to say certain large things and takes for the purpose whatever world one is capable of throwing up at the moment, and the theme rides as a kind of bridge, an afterthought, between two. Therefore, the better the world one can throw up at a moment, the better the book, I didn’t write Naked because I wanted to say war was horrible, or that history is complex, resistant, and almost inscrutable, or because I wanted to say that the coming battle between the naked fanatics and the dead mass was approaching, but because really what I wanted to say was, “Look at me, Norman Mailer, I’m alive, I’m a genius, I want people to know that; I’m a cripple, I want to hide that,” and so forth. The world at my disposal happened to be the Army, thank God, rather than unhappy couples boffing one another up in Wellfleet on the Cape. But the need came first, with world (material) second, and the theme last.)…

All the best,

Norm

To William Styron

Mexico

August 18, 1954

Dear Bill,

I wanted to answer your letter immediately when I got it because I truly appreciated the “critique” [of a draft of The Deer Park ]. But I was mixed up in reading one David Riesman14 for an article I wrote for Dissent, and somehow the weeks went by. (As if I had to explain a phenomenon like that to you!)

Anyway, the amazing thing to me was how similar your reaction to The Deer Park15 is to mine, or at least would be if hypothetically someone else had written it, and I had read it. For in a way I admire it too, and I also don’t like it—don’t like it in the sense that I don’t want to write more books like it, and hope this is the last of its sort, for the thing is really too painful. There’s a kind of destruction of the value of life almost implicit in it. By now I feel quite cool toward it (maybe I’ll warm up when I read the galleys) and really feel glad it’s done, and at the moment at least I can face the critics with some equanimity—the sons of bitches. But in reading your letter I understood why I was so eager for your reaction—because it is truly amazing how similar are our standards and tastes about books considering how different we are. So I suppose what I wanted in essence was my own reaction, only via you.

The only thing which depressed me about The Deer Park is that somewhere along the way I missed the boat. I still think it could have been a great novel, with a great dryness similar say to The Red and the Black, but my imagination and my daring and my day to day improvisation dried up a little too much, and the result is the result. What makes me feel cheerful is that I think I’m coming out of a five-year depression where writing, just the act, became progressively more depressing. Of course I’m not writing now. But I do feel as if some kind of pressure is off. I suppose what it is that whether I end up mediocre, good, or great, at least I know I’m a writer, and I haven’t known it all these years.

When you wrote of your own depression16 I was going first to embark on a long lecture in which I furnished you with all kinds of valuable precepts drawn from my own depression and mastery of it, Hark! Hark! But a day or two’s reflection showed me how pompous it was. And also I remember how utterly disheartening was the comfort of my friends with all their remarks about what do you want to become a psychoanalyst for or a businessman, etc., why, boy, you don’t realize how much talent you have. And of course what put the knife in my heart was that finally I had to do the writing, not them, and they just didn’t know. So I don’t want to go on about how much talent you have, etc. cause that won’t cheer you. But I do want to remind you that the writing depression may not last forever, and that what you learn now and what you accomplish now (even if it be half as much at twice the effort) is going to represent later the years when we got iron in our spines and lead in our pencils. After all, we’re both like bullfighters who arrived too early.—The thing I love more and more about bullfighting is its panoramic violent extrapolation of the agony of the artist, the half-artist, and the never-will-be artist. Whereas all our dramas go on in wormy corners of the brain….

Abrazos,

Norm

To James Jones17

August 25, 1955

Dear Jim,

I’ve been planning for months to answer your letter18 with a real long one, and now that the time has come, I don’t know how far I’ll get, because I’m empty, vitiated, flat, bored, wrung out rag-like, and all the other states that I guess you know as well as me. I finally finished The Deer Park, and a trip like that I never want again. It was really weird, Jim. I had the book done last summer, and I wasn’t satisfied with it, but I’d worked my balls off for three years and I had come to figure well the hell with it, you can’t stay on one book all your life. Then in November with the thing in page proof Stanley Rinehart insisted I take out six lines. You know, it never fails, whenever a publisher wants you to take out something, it always ends up being the most important thing in the book. So I told him no, and the son of a bitch broke his contract, and of course the shit had hit the fan. All through publishing the word was out that the new Mailer must really be a dog if Rinehart lets go of one of his two name writers (the other being Philip Wylie19 ). So it went to six houses, and each one had something different to object to, or dislike. By the time Putnam took it, I was as mad as I had been at any time since the Army because the book as it stood then had faults, but it was still so much better than the kind of shit which is printed all the time that I was livid enough to publish it myself.

Anyway, Putnam took it in January, and along about February I decided I’d touch up the Rinehart galleys a little bit because there were places where I began to see after a two-year drought how to improve it. So then a totally weird thing happened, Jim. As I started to work, the book kept changing and getting better, and before I was through six months went by, and I rewrote the Rinehart galleys, and then rewrote the new typewritten manuscript, and then by God rewrote the Putnam galley, and for six months I worked on it like I’ve never worked on anything. I think the key to it all was that I discovered I was much more of a fighter than I had thought I was, and that gave me the self-respect to really dig in. The word around town now is that I have cleaned it up, which of course is just about what one would expect after working your balls off, and making the novel more outrageous, more wild, more “it” than it was before. Anyway, I know what writer’s exhaustion is now. I have real post-delivery physical depression now.

There’re supposed to be copies ready on Sept. 7th, and I’ll send the signed copies to you and Lowney as soon as they arrive. And after you read it, I want a long evaluation of it from you, because that’s one of the few pleasures we get from writing is to know what a few real professional friends think.

Incidentally, Jimbo, The Deer Park is going to make you ill. Envious-ill, admiring-ill, wistful-ill, etc. And knowing you, competitive-ill. Which is all to the good. Because it’s a good enough novel (I think it’s better than Naked—smaller but deeper) and new enough to make it tough to read while you’re on your own stuff. At least if you’re like me. I remember when I read Eternity, I was sick with grippe at the time and I just got sicker. Because deep in me I knew that no matter how I didn’t want to like it, and how I leaped with pleasure on all its faults, it was still just too fucking good, and I remember the still artist’s voice in me saying, “Get off your ass, Norman, there’s big competition around.” But what the hell, I don’t have to explain it to you. I think in a way Styron, you, and me, are like a family. We’re competitive with each other, and yet let one of the outsiders start to criticize and we go wild. And there’s a reason for it, too. I think our books clear ground for one another. I opened ground for you, you opened ground for me, and I think and hope The Deer Park is going to open sexual ground, because as Calder [Willingham] reported maliciously but truthfully the book is all about “fucking.” And anyway as writers we’re all prison inmates serving life terms. So tell me exactly what you think about The Deer Park, and if you don’t like it, I’ll be furious at you, but if your reasons are good enough, I’ll finally accept them. Incidentally, one funny thing about it is that everybody who’s read it a second time digs it much more the second time. Because it’s a very funny book. I don’t know a single one like it.

Enough about me for the time being. I loved your letter, and I knew the whole business you feel about working with your hands. I’ve never done that steadily, but occasionally I’ve given a week or a month to such things as putting in the plumbing in the old cold water flat, and I don’t suppose I’ve ever been happier. And in Vermont when I was living there about five years ago, I had power tools and even built a little furniture, although as my ex-wife commented acidly once, “Norman’s hobby is to buy power tools and build stands for them.” And I had a workbench which I was proud as hell of because I built it out of a hundred year old plank which was over two feet wide and more than six inches thick and was irregular enough so that every one of the supporting legs was of a different size and bevel to support it. But it ended up so solid that I swear I think you could have dropped a truck on it….

Love from one old man to another,

Norm

P.S. You know I think we’re a vanishing breed. Half the writers in New York are becoming television writers, and I really think that there will be very few professional novelists like us in a couple of years, maybe ten.

This Issue

February 26, 2009

-

1

The author of the novels Lie Down in Darkness (1951), TheConfessions of Nat Turner (1967), Sophie’s Choice (1979), and a memoir, Darkness Visible (1990). His novella “The Long March” was published in the journal Discovery in February 1953 and as a book in 1956. Mailer and Styron fell out in 1956 and did not speak to one another for many years.

↩ -

2

Styron’s 1951 novel of Southern decadence and despair won the Rome Prize and launched his career.

↩ -

3

Styron married Rose Burgunder in Rome in May 1953; they remained married until his death in November 2006.

↩ -

4

Mailer and Adele traveled to Arkansas, Illinois, New Orleans, and Mexico from June to October 1953.

↩ -

5

Author of a score of novels, essays, and travel books, Ford (1873–1939) wrote Parade’s End, a tetralogy about World War I (in which he served), from 1924 to 1928. A Man Could Stand Up (1926) is the third volume.

↩ -

6

Jones underwrote the Handy Writers’ Colony in Marshall, Illinois, and lived there until 1957. Mailer’s friendship with Jones, established by their service in the Pacific theater and the blockbuster novels they wrote based on their experiences, was stronger than those with other writers of his generation. Yet they were competitive. Mailer’s copy of From Here to Eternity is inscribed as follows: “For Norman, my most feared friend, my dearest rival.”

↩ -

7

Jones’s mentor, lover, and, later, his partner in running the Handy Writers’ Colony. Handy (1904–1964) believed she could turn anyone with the requisite desire into a writer. Sixteen novels, including two by Jones, From Here to Eternity (1951) and Some Came Running (1957), as well as Tom Chamales’s Never So Few (1957) and Jere Peacock’s Valhalla (1961), all came out of the colony. See John Bower’s memoir, The Colony (1971), which describes Mailer’s visit to the Handy Writers’ Colony.

↩ -

8

Born in 1922, the author of ten novels and numerous short stories and critical articles. His first novel, The End of My Life (1947), is about an American soldier during World War II.

↩ -

9

A novelist and cowriter of the screenplays for the films Paths of Glory (1957) and The Graduate (1967), Willingham (1922–1995), originally from Georgia, lived in New York and was friendly with Mailer, Truman Capote, and Gore Vidal.

↩ -

10

A prolific literary critic, reviewer in mainstream publications, and professor at the University of Michigan, Aldridge (1922–2007) had a long and warm relationship with Mailer and was his neighbor in Connecticut in the late 1950s. For a time in the 1960s, he was Mailer’s authorized biographer.

↩ -

11

Born Wladimir Malacki to secular Jewish parents in Poland, Malaquais (1908–1998) was a laborer, soldier (fighting with a Marxist militia in the Spanish civil war and with France during World War II), and writer whose novels about European itinerants, among them Les Javanais and Planète sans visa, were greatly admired in Europe. Malaquais escaped to Venezuela in 1943 and eventually came to the US. Mailer promoted his work in the US; Malaquais translated The Naked and the Dead into French.

↩ -

12

Screenplay writer, novelist, and biographer, Shulman (1913–1996) is best known for writing the screenplay for Rebel without a Cause (1955), starring James Dean.

↩ -

13

Unknown.

↩ -

14

In his Dissent review (autumn 1954), Mailer called Riesman’s Individualism Reconsidered (1954) “boring.” He also discussed another book by Riesman (1909–2002), The Lonely Crowd (1951), and found greater merit in it.

↩ -

15

Styron said in his letter, “I don’t like The Deer Park, but I admire the sheer hell out of it.”

↩ -

16

Styron was depressed off and on for many years and wrote a memoir about it, Darkness Visible: A Memoir of Madness (1990).

↩ -

17

Jones (1921–1977) is best known for his novel From Here to Eternity, which won the National Book Award in 1952.

↩ -

18

Jones wrote Mailer a long letter on May 3, 1955, in which he discussed love, friendship, working with his hands, and “the slime and crud of Hollywood.” Reflecting on the writers of their generation, Jones said, “Ive [ sic ] only met two real writers besides myself, and that’s you and Billy [Styron].”

↩ -

19

Author of philosophical adventure fiction and nonfiction, Wylie (1902–1971) is perhaps best remembered for A Generation of Vipers (1942).

↩