“Does practice ever square with theory?” One way of resolving Plato’s rhetorical question is to turn it around and ask whether theory can ever be made to square with reality and, if so, what the nature of that reality is and why theory feels the need for a harmonious relationship with it. Among the realities with which political and social theories deal are the realities of power, exploitation, inequality, and low motives in high places. It is essential to deal initially with such matters of power, profit, and injustice because people are prone to adopt illusions and to accept euphemisms in order to endure. Without a critical viewpoint, theory tends to be apology or ideology, and then the only interesting question is whether innocence or preference has caused this to be so. Criticism of particular abuses is a necessary but not a sufficient condition of theory. The theorist must always be open to the possibility that reality may not simply be flawed by a few anomalies but may be systematically and rationally deranged.

These considerations are important in appraising The American University because it promises more than its title implies. It claims to be “both an empirical and a theoretical work”; an examination of American higher education and its “crisis”; and an illumination of “the modern world” in which education is “the most critical single feature…of modern societies.” Its credentials are impeccable. Talcott Parsons is one of the most famous living sociological theorists. Neil Smelser, perhaps his ablest student, has contributed an epilogue to the volume. The study was commissioned by the American Academy of Arts and Sciences and partly subsidized by the National Science Foundation. An “editorial associate” was enlisted to prune Parsons’s thickety style. Save for Smelser’s contribution, the result is a muddle which conceals a nightmare.

The main faults of the volume are not its obvious repetitiousness, contradictions, omissions, and innocence;1 not its myopic survey of the American university from a redoubt behind the Charles River; not its ignorance of all things left, from Marx to the dissident students; or its reduction of the Vietnam war to two insignificant footnotes; or its persistent habit of acknowledging criticisms of the university and then feeling entitled to ignore them; or the odd diagnosis that the threat to the university has issued from the “expressive-aesthetic sphere” and its “extremists” who “have advocated virtual equal status in the university of the creative and performing arts with the intellectual disciplines and even tipping the balance in favor of the former on the ground that the intellect is not truly creative” (p. 46). Nor is it the book’s worst fault that it takes nearly four hundred bloodless pages to recite how the academic “system” discharges its “fiduciary responsibility” by promoting standards of “rationality” according to “sharply defined and common evaluative standards” in which “the use of economic incentives and of authority and power is minimized, though not wholly absent” (pp. 123-124, 130).

Smelser corrects this picture of the “cognitive complex”—Parsons’s word for universities—by reminding us of certain realities: that during the Great Leap Forward of the Fifties and early Sixties, some academic departments and disciplines became considerably fatter than others; that the house of “cognitive rationality” also served as a supermarket of services and occupational training; that life could get bloody when the scholars sat down to divide the budgetary spoils; that the academy has become bureaucratized; that entrepreneurial activities have spread some faculty talents a little thin; that junior faculty and graduate assistants are ill-rewarded for their teaching; and that as the great universities scramble for prestige, hundreds of lesser institutions languish in a wasteland.

The real faults lie deeper, in Parsons’s conception of theory and in the resulting connections he makes between the theory and the world. To begin with, Parsons does not give us a theory which emerges from investigation of the university as such. Rather he applies to the university the theory of society which he has been busily constructing over the years. The main concern of this theory has been to identify the “functional requirements” which all “social systems” must fulfill if they are to “adapt” to their “environments.” Everything in the world belongs to one or another system or “subsystem,” and everything interlocks to produce “greater stability,” “integration,” and a “higher level of organization.” Since, in Parsons’s view, the university is part of a subsystem which helps to sustain the social system, it is theoretically interesting and socially important only in so far as it serves that end.

The application of this theory requires that the life of the university be defined to fit the categories of the theory. For example, he makes extensive use of economic categories and so he describes the development of academic disciplines as “the packaging of pure cognitive output” and the elective system as a kind of market arrangement under which “academic disciplines proved salable to undergraduates” (p. 122). Now the point is not that the formulation is crude or that there is no “truth” to it. Academic life does indeed have its share of vulgar commercialism; the question for a critical theory would be, do these vulgarities point to deep trouble? For Parsons, however, the symptoms are seen as part of a rational scheme and they have a function in that scheme. Not only does the malaise of the universities become an element of the normal operation of the academic system but the system itself is greeted as the “culmination” of the “educational revolution” and near-fascimile of the “ideal type” (p. 3).

Advertisement

In important respects, the viewpoint which informs Parsons’s theory derives from one of the main traditions of sociological theory, the preoccupation with order and stability. We see this concern at work in the opening pages, where he identifies the educational, industrial, and democratic “revolutions” as the major “progressive” forces of our time; in the main part of the book where he constantly worries about the “tensions” between equality and inequality, freedom and constraint, between the “cognitive” and the “affective”; and in his views about the recent campus discontents (“Obviously the issue is one of balance between stability and change,” p. 362). Throughout his book Parsons re-echoes the concern of classical sociology to find the formula for combining freedom and order, progress and stability. From Saint-Simon and Comte to Durkheim and Weber, the peculiarity of the sociological tradition has been that it has concentrated on order and has been relatively indifferent to freedom.2 Neither Durkheim nor Weber, for example, both of whom were encyclopedic in their range of inquiry, ever addressed the topic of revolution systematically. Durkheim even attempted a history of nineteenth-century socialism which omitted Marx.

These reminders are pertinent because Parsons frequently cites Durkheim and Weber as authorities. His use of Weber is particularly instructive, for Parsons has done more than anyone else to make Weber a household word among American sociologists. Now in Parsons’s account of the university the key word is “rationality.” The faculty cultivates it; the students are “socialized” into acquiring it; and the larger society is supplied with it by the university. For Weber rationality was the key to “rationalization,” the distinctive process of Western societies and the product of a mode of thinking and acting by which all things and persons tend to become objects to be manipulated according to canons of efficiency and a calculus of means and ends. Weber saw bureaucratization as the most powerful expression of rationalization: objective, depersonalized, specialized expertise, and unvarying routines. The irresistible trend toward the bureaucratic, he believed, had created an “iron cage” for those who were truly devoted to their vocations. For Weber, then, the rational order had become a cause for despair.

But there is no despair in Parsons. He is “relatively optimistic” as he celebrates the world created by “instrumental activism.” At a time when every scribbler in the land is aware of widespread moral confusion, Parsons perseveres in the faith that “there is and has been a single, relatively well-integrated value-system [of instrumental activism] institutionalized in the society which has ‘evolved’ but has not been drastically changed” (p. 40).

Aside from its occasional euphoria, the problem with Parsons’s theory is not its failure to depict reality, but to comprehend the meaning of what it has grasped. It extols, for example, “institutionalized individualism” as “the emerging pattern in modern societies” (p. 42). But since the ideal of this institutionalization is, in his incredible prose, to have “the goal-interest of the unit coincide with the functional significance of its contribution from the point of view of the subsystem” (p. 34) we have only an idealized version of the iron cage.

Little is to be gained by following out Parsons’s vision of the university. He finds economic analogies “intriguing” and so it becomes a question for him of how a “deficit” system (i.e., one which doesn’t make money) can produce “outputs” that will satisfy society. He theorizes that the university discharges its debts by socializing undergraduates, turning out professionals, and turning on intellectuals whose function is to supply the public with ideological “definitions of the situation.” The campus crises of the Sixties are analyzed according to a monetary model of inflation and deflation. The university is likened to an “influence bank” in which the community has “invested” its loyalty. A “deflationary panic” occurred in the Sixties because some of the depositors began to prefer anti-intellectual and non-material goods. They dropped out and the community “withdrew” its trust.

Typically Parsons’s analogies begin as euphemisms and end in mystification. Thus he defends his choice of this economic model over other ones, such as the “political” and “bureaucratic” models, because he finds it exceedingly distasteful to discuss questions of power and domination in the academy. Apparently it does not occur to him that a model which reduces education to a commodity can hardly be less depersonalizing than any bureaucratic model; or that economic categories are less power-laden than political ones.

Advertisement

The clearest expression of the night-marish quality of Parsons’s vision is in his discussion of the undergraduate “sector.” He is particularly concerned with “studentry,” as he likes to call the undergraduates, because he believes that the recent discontents originated there. Accordingly it is “socialization,” not independence of mind or critical judgment, that dominates his discussion of undergraduate education, which he believes should be “conceived” as an organic metaphor, “the mammalian system of reproduction.” This refers to the “prolonged period” of immaturity which necessitates “care and socialization by adult human agents before the child can become independent” (p. 150).

The university, he suggests, should perform this role in a way analogous to that of psychotherapy. But as Parsons’s description continues, it is apparent that the university is being urged to administer a species of brain-washing. When the student enters the university, Parsons writes, he leaves behind various ties of family and community (“dedifferentiation”); his impulse is toward “undifferentiated” and “absolute moralism” and toward “equalitarianism.” As a result, he seeks close solidarity with his peers (rather than with the faculty), for “total commitment” and “absolute participation.” At this point the university intervenes. It teaches the undergraduate to develop multiple loyalties and “differentiated” participation. It breaks up (“substantially modifies”) the support which students give to each other and thereby enables “personality reorganization and growth” to be achieved. The student will adopt the success ethic (“differential achievement”) and internalize “the values of the academic community.” This system, with its “manipulation of rewards,” is designed to give students a “sense of self-esteem” (pp. 168-178).

It would be misleading to leave the impression that Parsons has given a prescription for the university that ignores the grievances voiced during the Sixties. The contrary is true. He advocates more attention to teaching; relaxation of the curriculum; greater student participation; more blacks, women, and older people; a greater injection of “affect” into education so as to “balance” off the rigorous demands of the rat-cog faculty. In short, he wants just about every consumer demand to be satisfied so long as the demand isn’t also political. And yet this openness seems less a matter of generosity than of cooptation made possible by the fact that Parsons accepts everything that has been housed in the university in the past. He is correct in claiming that he has “differentiated” the university from other “systems”; but he has not distinguished it.

Parsons has concocted the perfect response to Plato, a theory which accords wonderfully well with the American power-world of science, technology, corporations, and other bureaucracies. Undoubtedly his undergraduates, processed to a fine point of competence and fortified by their daily dose of rationality and affect, should make it in that world. Parsons is also correct in claiming that his theory combines a “high level of generality” or “abstraction” with an empirical content. For the facts of life today are just that, abstract, impersonal, dehumanized. Like the denizens of Parsons’s university few of us experience the world immediately and we mostly live by abstract metaphors, snugly contained by our “institutionalized individualism,” pursuing the fantasies of power of our “instrumental activism,” and forever relieved of serious political commitments by an education which “focuses on the development of an ‘educated citizenry’…although not in the political sense.” A theory which can rationalize the eviction of man from his world is not only empirical but complicit for its endorsement of the processes of eviction and its connivance at the powerlessness of the evicted.

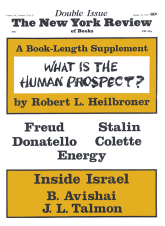

This Issue

January 24, 1974