I

Sometimes old India, the old, eternal India many Indians like to talk about, does seem just to go on. During the last war some British soldiers, who were training in chemical warfare, were stationed in the far south of the country, near a thousand-year-old Hindu temple. The temple had a pet crocodile. The soldiers, understandably, shot the crocodile. They also in some way—perhaps by their presence alone—defiled the temple. Soon, however, the soldiers went away, and the British left India altogether. Now, more than thirty years after that defilement, and in another season of emergency, the temple has been renovated and a new statue of the temple deity is being installed.

Until they are given life and invested with power, such statues are only objects in an image-maker’s yard, their value depending on size, material, and the carver’s skill. Hindu idols or images come from the old world; they embody difficult and sometimes sublime concepts, and they have to be made according to certain rules. There can be no development now in Hindu iconography, though the images these days, under the influence of the Indian cinema and cinema posters, are less abstract than their ancient originals, and more humanly pretty and doll-like. They stand lifeless in every way in the image-maker’s showroom. Granite and marble—and an occasional commissioned bust of someone like a local inspector of police, with perhaps a real spectacle-frame over his blank marble eyes—suggest at first the graveyard, and a people in love with death. But this showroom is a kind of limbo, with each image awaiting the life and divinity that will come to it with purchase and devotion, each image already minutely flawed, so that its divine life, when it comes, shall not be terrible and overwhelming.

Life, then, has to be given to the new image in the once defiled temple. A special effort has to be made. And the method being used is one of the most archaic in the world. It takes us back to the beginning of religion and human wonder. It is the method of the word: in the beginning was the word. A twelve-lettered mantra will be chanted and written fifty million times; and that is what—in this time of Emergency, with the constitution suspended, the press censored—5,000 volunteers are doing. When the job is completed, an inscribed gold plate will be placed below the new idol, to attest to the creation of its divinity and the devotion of the volunteers. A thousand-year-old temple will live again: India, Hindu India, is eternal: conquests and defilements are but instants in time.

About 200 miles away, still in the south, on a brown plateau of rock and gigantic boulders, are the ruins of the capital city of what was once the great Hindu kingdom of Vijayanagar. Vijayanagar—vijaya, victory, nagar, city—was established in the fourteenth century; it was conquered, and totally destroyed, by an alliance of Moslem principalities in 1565. The city was then one of the greatest in the world, its walls twenty-four miles around—foreign visitors have left accounts of its organization and magnificence—and the work of destruction took five months; some people say a year.

Today all the outer city is a peasant wilderness, with scattered remnants of stone or brick structures. Near the Tungabhadra River are the grander ruins: palaces and stables, a royal bath, a temple with clusters of musical stone columns that can still be played, a broken acqueduct, the leaning granite pillars of what must have been a bridge across the river. There is more beyond the river: a long and very wide avenue, still partly façaded, with a giant statue of the bull of Shiva at one end and, at the other end, a miracle: a temple that for some reason was spared destruction 400 years ago, is still whole, and is still used for worship.

It is for this that the pilgrims come, to make offerings and to perform the rites of old magic. Some of the ruins of Vijayanagar have been declared national monuments by the Archaeological Department; but to the pilgrims—and they are more numerous than the tourists—Vijayanagar is not its terrible history or its present encompassing desolation. Such history as is known has been reduced to the legend of a mighty ruler, a kingdom founded with gold that showered from the sky, a kingdom so rich that pearls and rubies were sold in the market place like grain.

To the pilgrims Vijayanagar is its surviving temple. The surrounding destruction is like proof of the virtue of old magic; just as the fantasy of past splendor is accommodated within an acceptance of present squalor. That once glorious avenue—not a national monument, still permitted to live—is a slum. Its surface, where unpaved, is a green-black slurry of mud and excrement, through which the sandaled pilgrims unheedingly pad to the food stalls and souvenir shops, loud and gay with radios. And there are starved squatters with their starved animals in the ruins, the broken stone façades patched up with mud and rocks, the doorways stripped of the sculptures which existed until recently. Life goes on, the past continues. After conquest and destruction, the past simply reaserts itself.

Advertisement

If Vijayanagar is now only its name and, as a kingdom, is so little remembered (there are university students in Bangalore, 200 miles away, who haven’t even heard of it), it isn’t only because it was so completely wiped out, but also because it contributed so little; it was itself a reassertion of the past. The kingdom was founded in 1336 by a local Hindu prince who, after defeat by the Moslems, had been taken to Delhi, converted to Islam, and then sent back to the south as a representative of the Moslem power. There in the south, far from Delhi, the converted prince had re-established his independence and, unusually, in defiance of Hindu caste rules, had declared himself a Hindu again, a representative on earth of the local Hindu god. In this unlikely way the great Hindu kingdom of the south was founded.

It lasted 200 years, but during that time it never ceased to be embattled. It was committed from the start to the preservation of a Hinduism that had already been violated, and culturally and artistically it preserved and repeated; it hardly innovated. Its bronze sculptures are like those of 500 years before; its architecture, even at the time, and certainly to the surrounding Moslems, must have seemed heavy and archaic. And its ruins today, in that unfriendly landscape of rock and boulders of strange shapes, look older than they are, like the ruins of a long superseded civilization.

The Hinduism Vijayanagar proclaimed had already reached a dead end, and in some ways had decayed, as popular Hinduism so easily decays, into barbarism. Vijayanagar had its slave markets, its temple prostitutes. It encouraged the holy practice of suttee, whereby a widow burned herself on the funeral pyre of her husband, to achieve virtue, to secure the honor of her husband’s family, and to cleanse that family of the sins of three generations. And Vijayanagar dealt in human sacrifice. Once, when there was some trouble with the construction of a big reservoir, the great king of Vijayanagar, Krishna Deva Raya (1509-1529), ordered the sacrifice of some prisoners.

In the sixteenth century Vijayanagar, really, was a kingdom awaiting conquest. But it was big and splendid; it needed administrators, artists, craftsmen; and for the 200 years of its life it must have sustained all the talent of the land and concentrated it in that capital. When it was conquered and its capital systematically smashed, more than buildings and temples would have been destroyed. Many men would have been killed; all the talent, energy, and intellectual capacity of the kingdom would have been extinguished for generations. The conquerors themselves, by creating a desert, would have ensured, almost invited, their own subsequent defeat by others; again and again, for the next 200 years, the land of that dead kingdom was trampled down.

And today it still shows, the finality of that destruction of Hindu Vijayanagar in 1565: in the acknowledged “backwardness” of the region, which now seems without a history and which it is impossible to associate with past grandeur or even with great wars; in the squalor of the town of Hospet that has grown up not far from the ruins; in the unending nullity of the peasant-serf countryside.

Since Independence much money has been spent on the region. A dam has been built across the Tungabhadra River. There is an extensive irrigation scheme which incorporates the irrigation canals of the old kingdom (and these are still called Vijayanagar canals). A Vijayanagar steel plant is being planned; and a university is being built, to train men of the region for jobs in that steel plant and the subsidiary industries that are expected to come up. The emphasis is on training men of the region, local men. Because, in this land that was once a land of great builders, there is now a human deficiency. The state of which the region forms part is the one state in the Indian Union that encourages migrants from other states. It needs technicians, artisans; it needs men with simple skills; it needs even hotel waiters. All it has been left with is a peasantry that cannot comprehend the idea of change: like the squatters in the ruins outside the living Vijayanagar temple, slipping in and out of the decayed stone façades like brightly colored insects, screeching and unimportantly active on this afternoon of rain.

Advertisement

It was at Vijayanagar this time, in that wide temple avenue, which seemed less awesome than when I had first seen it thirteen years before, no longer speaking as directly as it did then of a fabulous past, that I began to wonder about the intellectual depletion that must have come to India with the invasions and conquests of the last thousand years. What happened in Vijayanagar happened, in varying degrees, in other parts of the country. In the north ruin lies on ruin: Moslem ruin on Hindu ruin, Moslem on Moslem. In the history books, in the accounts of wars and conquests and plunder, the intellectual depletion passes unnoticed, the lesser intellectual life of a country whose contributions to civilization were made in the remote past. India absorbs and outlasts its conquerors, Indians say. But at Vijayanagar, among the pilgrims, I wondered whether intellectually for a thousand years India hadn’t always retreated before its conquerors and whether, in its periods of apparent revival, India hadn’t only been making itself archaic again, intellectually smaller, always vulnerable.

In the British time, a period of bitter subjection which was yet for India a period of intellectual recruitment, Indian nationalism proclaimed the Indian past; and religion was inextricably mixed with political awakening. But independent India, with its five-year plans, its industrialization, its practice of democracy, has invested in change. There always was a contradiction between the archaism of national pride and the promise of the new; and the contradiction has at last cracked the civilization open.

The turbulence in India this time hasn’t come from foreign invasion or conquest; it has been generated from within. India cannot respond in her old way, by a further retreat into archaism. Her borrowed institutions; have worked like borrowed institutions; but archaic India can provide no substitutes for press, parliament, and courts. The crisis of India is not only political or economic. The larger crisis is of a wounded old civilization that has at last become aware of its inadequacies, and is without the intellectual means to move ahead.

II

“India will go on.” This was what the Indian novelist R.K. Narayan said to me in London in 1961, before I had ever been to India.

The novel, which is a form of social inquiry, and as such outside the Indian tradition, had come to India with the British. By the late nineteenth century it had become established in Bengal, and had then spread. But it was only toward the end of the British period, in the 1930s, that serious novelists appeared who wrote in English, for first publication in London. Narayan was one of the earliest and best of these. He had never been a “political” writer, not even in the explosive 1930s; and he was unlike many of the writers after Independence who seemed to regard the novel, and all writing, as an opportunity for autobiography and boasting.

Narayan’s concern had always been with the life of a small South Indian town, which he peopled book by book. His conviction in 1961, after fourteen years of independence, that India would go on, whatever the political uncertainties after Mr. Nehru, was like the conviction of his earliest novels, written in the days of the British, that India was going on. In the early novels the British conquest is like a fact of life. The British themselves are far away, their presence hinted at only in their institutions: the bank, the mission school. The writer contemplates the lesser life that goes on below: small men, small schemes, big talk, limited means: a life so circumscribed that it appears whole and unviolated, its smallness never a subject for wonder, though India itself is felt to be vast.

In his autobiography, My Days, published in 1974,1 Narayan fills in the background to his novels. This book, though more exotic in content than the novels, is of a piece with them. It is not more politically explicit or exploratory. The southern city of Madras—one of the earliest English foundations in India, the site leased by the East India Company in 1640 from the last remnant of the Vijayanagar kingdom—was where Narayan spent much of his childhood. Madras was part of a region that had long been pacified, was more Hindu than the north, less Islamized, and had had seventy-five years more of peace. It had known no wars, Narayan says, since the days of Clive. When, during the First World War, the roving German battleship Emden appeared in the harbor one night, turned on its searchlights and began shelling the city, people “wondered at the phenomenon of thunder and lightning with a sky full of stars.” Some people fled inland. This flight, Narayan says, “was in keeping with an earlier move, when the sea was rough with cyclone and it was prophesied that the world would end that day.”

The world of Narayan’s childhood was one that had turned in on itself, had become a world of prophecy and magic, removed from great events and removed, it might seem, from the possibility of politics. But politics did come; and it came, as perhaps it could only come, by stealth, and mingled with ritual and religion. At school Narayan joined the boy scouts. But the boy scout movement in Madras was controlled by Annie Besant, the Theosophist, who had a larger idea of Indian civilization than most Indians had at that time; and, in sly subversion of Lord Baden-Powell’s imperial purpose, the Besant scouts sang, to the tune of “God Save the King”: “God save our motherland, God save our noble land, God save our Ind.”

One day in 1919 Narayan fell in with a procession that had started from the ancient temple of Iswara. The procession sang “patriotic songs” and shouted slogans and made its way back to the temple, where there was a distribution of sweets. This festive and devout affair was the first nationalist agitation in Madras. And—though Narayan doesn’t say it—it was part of the first all-India protest that had been decreed by Gandhi, aged forty-nine, just three years back from South Africa, and until then relatively unknown in India. Narayan was pleased to have taken part in the procession. But his uncle, a young man and a modern man (one of the earliest amateur photographers in India), was less than pleased. The uncle, Narayan says, was “antipolitical and did not want me to be misled. He condemned all rulers, governments and administrative machinery as Satanic and saw no logic in seeking a change of rulers.”

Well, that was where we all began, all of us who are over forty and were colonials, subject people who had learned to live with the idea of subjection. We lived within our lesser world; and we could even pretend it was whole because we had forgotten that it had been shattered. Disturbance, instability, development lay elsewhere; we, who had lost our wars and were removed from great events, were at peace. In life, as in literature, we received tourists. Subjection flattened, made dissimilar places alike. Narayan’s India, with its colonial apparatus, was oddly like the Trinidad of my childhood. His oblique perception of that apparatus, and the rulers, matched my own; and in the Indian life of his novels I found echoes of the life of my own Indian community on the other side of the world.

But Narayan’s novels did not prepare me for the distress of India. As a writer he had succeeded almost too well. His comedies were of the sort that requires a restricted social setting with well-defined rules; and he was so direct, his touch so light, that, though he wrote in English of Indian manners, he had succeeded in making those exotic manners quite ordinary. The small town he had staked out as his fictional territory was, I knew, a creation of art and therefore to some extent artificial, a simplification of reality. But the reality was cruel and overwhelming. In the books his India had seemed accessible; in India it remained hidden.

To get down to Narayan’s world, to perceive the order and continuity he saw in the dereliction and smallness of India, to enter into his ironic acceptance and relish his comedy, was to ignore too much of what could be seen, to shed too much of myself: my sense of history, and even the simplest ideas of human possibility. I did not lose my admiration for Narayan; but I felt that his comedy and irony were not quite what they had appeared to be, were part of a Hindu response to the world I could no longer share. And it has since become clear to me—especially on this last visit, during a slow rereading of Narayan’s 1949 novel Mr. Sampath2—that, for all their delight in human oddity, Narayan’s novels are less the purely social comedies I had once taken them to be than religious books, at times religious fables, and intensely Hindu.

Srinivas, the hero of Mr. Sampath, is a contemplative idler. He has tried many jobs—agriculture, a bank, teaching, the law: the jobs of pre-Independence India—the year is 1938—and rejected all. He stays in his room in the family house—the house of the Indian extended family—and worries about the passing of time. Srinivas’s elder brother, a lawyer, looks after the house, and that means he looks after Srinivas and Srinivas’s wife and son. The fact that Srinivas has a family is as much a surprise as Srinivas’s age: he is thirty-seven.

One day Srinivas is reading the Upanishads in his room. His elder brother comes in and says, “What exactly is it that you wish to do in life?” Srinivas replies: “Don’t you see? There are ten principal Upanishads. I should like to complete the series. This is the third.” But Srinivas takes the hint. He decides to go to the town of Malgudi and set up a weekly paper. In Malgudi he lives in a squalid rented room in a crowded lane, bathes at a communal water-tap, and finds an office for his paper in a garret.

Srinivas is now in the world, with new responsibilities and new relationships—his landlord, his printer, his wife (“he himself wondered that he had observed so little of her in their years of married life”)—but he sees more and more clearly the perfection of non-doing. “While he thundered against municipal or social shortcomings a voice went on asking: ‘Life and the world and all this is passing—why bother about anything? The perfect and the imperfect are all the same. Why really bother?” ”

His speculations seem idle, and are presented as half comic; but they push him deeper into quietism. From his little room one day he hears the cry of a woman selling vegetables in the lane. Wondering first about her and her customers, and then about the “great human forces” that meet or clash every day, Srinivas has an intimation of “the multitudinousness and vastness of the whole picture of life,” and is dazzled. God, he thinks, is to be perceived in that “total picture”; and later, in that total picture, he also perceives a wonderful balance. “If only one could get a comprehensive view of all humanity, one would get a correct view of the world: things being neither particularly wrong nor right, but just balancing themselves.” There is really no need to interfere, to do anything. And from this Srinivas moves easily, after a tiff with his wife one day, to a fuller comprehension of Gandhian non-violence. “Non-violence in all matters, little or big, personal or national, it seemed to produce an unagitated, undisturbed calm, both in a personality and in society.”

But this nonviolence or nondoing depends on society going on; it depends on the doing of others. When Srinivas’s printer closes his shop, Srinivas has to close his paper. Srinivas, then, through the printer (who is the Mr. Sampath of Narayan’s title), finds himself involved as a scriptwriter in the making of an Indian religious film. Srinivas is now deeper than ever in the world, and he finds it chaotic and corrupt. Pure ideas are mangled; sex and farce, song and dance and South American music are grafted on to a story of Hindu gods. The printer, now a kind of producer, falls in love with the leading lady. An artist is in love with her as well. The printer wins, the artist literally goes mad. All is confusion; the film is never made.

Srinivas finally withdraws. He finds another printer and starts his paper again, and the paper is no longer the comic thing it had first seemed. Srinivas has, in essence, returned to himself and to his contemplative life. From this security (and with the help of some rupees sent him by his brother: always the rupees: the rupees are always necessary) Srinivas sees “adulthood” as a state of nonsense, without innocence or pure joy, the nonsense given importance only by “the values of commerce.”

There remains the artist, made mad by love and his contact with the world of nonsense. He has to be cured, and there is a local magician who knows what has to be done. He is summoned, and the antique rites begin, which will end with the ceremonial beating of the artist. Tribal, Srinivas thinks: they might all be in the twentieth century BC. But the oppression he feels doesn’t last. Thinking of the primitive past, he all at once has a vision of the millennia of Indian history, and of all the things that might have happened on the ground where they stand.

There, in what would then have been forest, he sees enacted an episode from the Hindu epic of the Ramayana, which partly reflects the Aryan settlement of India (perhaps 1000 BC). Later, the Buddha (about 560-480 BC) comforts a woman whose child has died: “Bring me a handful of mustard seed from a house where no one has died.” The philosopher Shankaracharya (788-820 AD), preaching the Vedanta on his all-India mission, founds a temple after seeing a spawning frog being sheltered from the sun by its natural enemy, the cobra. And then the missionaries from Europe come, and the merchants, and the soldiers, and Mr. Shilling, who is the manager of the British bank which is now just down the road.

“Dynasties rose and fell. Palaces and mansions appeared and disappeared. The entire country went down under the fire and sword of the invader, and was washed clean when Sarayu overflowed its bounds. But it always had its rebirth and growth.” Against this, what is the madness of one man? “Half the madness was his own doing, his lack of self-knowledge, his treachery to his own instincts as an artist, which had made him a battleground. Sooner or later he shook off his madness and realized his true identity—though not in one birth, at least in a series of them…. Madness or sanity, suffering or happiness seemed all the same…in the rush of eternity nothing mattered.”

So the artist is beaten, and Srinivas doesn’t interfere; and when afterward the magician orders the artist to be taken to a distant temple and left outside the gateway for a week, Srinivas decides that it doesn’t matter whether the artist is looked after or not during that time, whether he lives or dies. “Even madness passes,” Srinivas says in his spiritual elation. “Only existence asserts itself.”

Out of a superficial reading of the past, then, out of the sentimental conviction that India is eternal and forever revives, there comes, not a fear of further defeat and destruction, but an indifference to it. India will somehow look after itself; the individual is freed of all responsibility. And within this larger indifference there is the indifference to the fate of a friend: it is madness, Srinivas concludes, for him to think of himself as the artist’s keeper.

Just twenty years have passed between Gandhi’s first call for civil disobedience and the events of the novel. But already, in Srinivas, Gandhian nonviolence has degenerated in something very like the opposite of what Gandhi intended. For Srinivas nonviolence isn’t a form of action, a quickener of social conscience. It is only a means of securing an undisturbed calm; it is nondoing, noninterference, social indifference. It merges with the ideal of self-realization, truth to one’s identity. These modern-sounding words, which reconcile Srinivas to the artist’s predicament, disguise an acceptance of karma, the Hindu killer, the Hindu calm, which tells us that we pay in this life for what we have done in past lives: so that everything we see is just and balanced, and the distress we see is to be relished as religious theater, a reminder of our duty to ourselves, our future lives.

Srinivas’s quietism—compounded of karma, nonviolence, and a vision of history as an extended religious fable—is in fact a form of self-cherishing in the midst of a general distress. It is parasitic. It depends on the continuing activity of others, the trains running, the presses printing, the rupees arriving from somewhere. It needs the world, but it surrenders the organization of the world to others. It is a religious response to worldly defeat.

Because we take to novels our own ideas of what we feel they must offer, we often find, in unusual or original work, only what we expect to find, and we reject or miss what we aren’t looking for. But it astonished me that, twenty years before, not having been to India, taking to Mr. Sampath only my knowledge of the Indian community of Trinidad and my reading of other literature, I should have missed or misread so much, should have seen only a comedy of small-town life and a picaresque, wandering narrative in a book that was really so mysterious.

Now, reading Mr. Sampath again in snatches on afternoons of rain during this prolonged monsoon, which went on and on like the Emergency itself—reading in Bombay, looking down at the choppy sea and the 1911 imperial rhetoric of the British-built Gateway of India, dwarfing the white-clad crowd; in suburban and secretive New Delhi, looking out across the hotel’s sodden tennis court to the encampment of Sikh taxi drivers below the dripping trees; on the top verandah of the Circuit House in Kotah, considering the garden, and seeing in mango tree and banana tree the originals of the stylized vegetation in the miniatures done for Rajput princes, their glory now extinguished, their great forts now abandoned and empty, protecting nothing, their land now only a land of peasants; in Bangalore in the south, a former British army town, looking across the parade ground, now the polo ground, with Indian army polo teams—reading during the Emergency, which was more than political, I saw in Mr. Sampath a foreshadowing of the tensions that had to come to India, philosophically prepared for defeat and withdrawal (each man an island) rather than independence and action, and torn now between the wish to preserve and be psychologically secure, and the need to undo.

From the Indian Express: “New Delhi, Sept 2 … Inaugurating the 13th conference of the chairmen and members of the State Social Welfare Advisory Boards here, Mrs. Gandhi said stress on the individual was India’s strength as well as weakness. It had given the people an inner strength but had also put a veil between the individual and others in society…. Mrs. Gandhi said no social welfare programme could succeed unless the basic attitudes of mind change…. ‘We must live in this age,’ Mrs. Gandhi said, adding that this did not mean that ‘we must sweep away’ all our past. While people must know of the past, they must move towards the future, she added.”

The two ideas—responsibility, the past—were apparently unrelated. But in India they hung together. The speech might have served as a commentary on Mr. Sampath. What had seemed speculative and comic, aimless and “Russian” about Narayan’s novel had turned out to be something else, the expression of an almost hermetic philosophical system. The novel I had read as a novel was also a fable, a classic exposition of the Hindu equilibrium, surviving the shock of an alien culture, an alien literary form, an alien language, and making harmless even those new concepts it appeared to welcome. Identity became an aspect of karma, self-love was bolstered by an ideal of nonviolence.

III

To arrive at an intellectual comprehension of this equilibrium—as some scholars do, working in the main from Hindu texts—is one thing. To enter into it, when faced with the Indian reality, is another. The hippies of Western Europe and the United States appear to have done so; but they haven’t. Out of security and mental lassitude, an intellectual anorexia, they simply cultivate squalor. And their calm can easily turn to panic. When the price of oil rises and economies tremble at home, they clean up and bolt. Theirs is a shallow narcissism; they break just at that point where the Hindu begins: the knowledge of the abyss, the acceptance of distress as the condition of men.

It is out of an eroded human concern, rather than the sentimental wallow of the hippies and others who “love” India, that a dim understanding begins to come. And it comes at those moments when, in spite of all that has been done since Independence, it seems that enough will never be done; and despair turns to weariness, and thoughts of action fade. Such a moment came to me this time in North Bihar. Bihar, for centuries the cultural heartland of India (“Bihar” from vihara, a Buddhist monastery), now without intellect or leaders: in the south a land of drought and famine and flood, in the north a green, well-watered land of jute (like tall reeds) and paddy and fishponds.

In the village I went to only one family out of four had land; only one child out of four went to school; only one man out of four had work. For a wage calculated to keep him only in food for the day he worked, the employed man, hardly exercising a skill, using the simplest tools and sometimes no tools at all, did the simplest agricultural labor. Child’s work; and children, being cheaper than men, were preferred; so that, suicidally, in the midst of an overpopulation which no one recognized (an earthquake in 1935 had shaken down the population, according to the villagers, and there had been a further thinning out during the floods of 1971), children were a source of wealth, available for hire after their eighth year, if times were good, for fifteen rupees, a dollar fifty, a month.

Generation followed generation quickly here, men as easily replaceable as their huts of grass and mud and matting (golden when new, quickly weathering to gray-black). Cruelty no longer had a meaning; it was life itself. Men knew what they were born to. Every man knew his caste, his place; each group lived in its own immemorially defined area; and the pariahs, the scavengers, lived at the edge of the village. Above the huts rose the rambling two-story brick mansion of the family who had once owned it all, the land and the people: grandeur that wasn’t grandeur, but was like part of the squalor and defeat out of which it had arisen. The family was now partially dispossessed but, as politicians, they still controlled. Nothing had changed or seemed likely to change.

And during the rest of that day’s drive North Bihar repeated itself: the gray-black hut clusters; the green paddy fields whose luxuriance and springlike freshness can deceive earth-scanners and cause yields to be overestimated; the bare-backed men carrying loads on either end of a long, limber pole balanced on their shoulders, the strain showing in their brisk, mincing walk, which gave them a curious feminine daintiness; the overcrowded buses at dusty towns that were shack-settlements; the children wallowing in the muddy ponds in the heat of the day, catching fish; the children and the men pounding soaked jute stalks to extract the fiber which, loaded on bullockcarts, looked like thick plaited blond tresses, immensely rich. Thoughts of human possibility dwindled; North Bihar seemed to have become the world, capable only of the life that was seen.

It was like the weariness I had felt some weeks before, in the Bundi-Kotah region of Rajasthan, 800 miles to the west. If in North Bihar there had seemed to be, with the absence of intellect and creativity, an absence almost of administration, here in Rajasthan was prodigious enterprise. Here were dams and a great irrigation-and-reclamation scheme in a land cut up and wasted by ravines.

Imperfectly conceived twenty years before—no drainage, the nature of the soil not taken into account—the irrigation scheme had led to waterlogging and salinity. Now, urgently, this was being put right. There was a special commissioner, and he and his deputies were men of the utmost energy. The technical problems could be solved. The difficulties—in this state of desert forts, feudal princes, and a peasantry trained only in loyalty, equipped for little else—lay with the people: not just with the “mediocrity at every level” which the commissioner said he found in the administration, but also with the people lower down, whom the scheme was meant to benefit. How could they, used for generations to so little, content to find glory only in the glory of their rulers, be made now, almost suddenly, to want, to do?

The commissioner’s powers were great, but he was unwilling to rule despotically; he wished to “institutionalize.” One evening, by the light of an electric bulb—electricity in the village!—we sat out with the villagers in the main street of a “model village” of the command area. The street was unpaved, and the villagers, welcoming us, had quickly spread cotton rugs on the ground that had been softened by the morning’s rain, half hardened by the afternoon’s heat, and then trampled and manured by the village cattle returning at dusk. The women had withdrawn—so many of them, below their red or orange Rajasthani veils, only girls, children, but already with children of their own. We were left with the men; and, until the rain came roaring in again, we talked.

So handsome, these men of Rajasthan, so self-possessed: it took time to understand that they were only peasants, and limited. The fields, water, crops, cattle: that was where concern began and ended. They were a model village, and so they considered themselves. There was little more that they needed, and I began to see my own ideas of village improvement as fantasies. Nothing beyond food—and survival—had as yet become an object of ambition; though one man said, fantastically, that he would like a telephone, to find out about the price of grain in Kotah without having to go there.

The problems of the irrigation project were not only those of salinity or the ravines or land-leveling. The problem, as the commissioner saw, was the remaking of men. And this was not simply making men want; it meant, in the first place, bringing them back from the self-wounding and the special waste that come with an established destitution. We were among men who, until recently, cut only the very tops of sugar cane and left the rest of the plant, the substance of the crop, to rot. So this concern about fertilizers and yields, this acquiring by the villagers of what I had at first judged to be only peasant attributes, was an immeasurable advance.

But if in this model village—near Kotah Town, which was fast industrializing—there had been some movement, Bundi the next day seemed to take us backward. Bundi and Kotah: to me, until this trip, they had only been beautiful names, the names of related but distinct schools of Rajasthan painting. The artistic glory of Bundi had come first, in the late seventeenth century. And after the flat waterlogged fields, pallid paddy thinning out at times to marshland, after the desolation of the road from Kotah, the flooded ditches, the occasional cycle-rickshaw, the damp groups of bright-turbaned peasants waiting for the bus, Bundi Castle on its hill was startling, its great walls like the work of giants, the extravagant creation of men who had once had much to defend.

Old wars, bravely fought; but usually little more had been at stake other than the honor and local glory of one particular prince. The fortifications were now useless, the palace was empty. One dark, dusty room had old photographs and remnants of Victorian bric-a-brac. The small formal garden in the courtyard was in decay; and the mechanical, decorative nineteenth-century Bundi murals around the courtyard had faded to blues and yellows and greens. In the inner rooms, hidden from the sun, brighter colors survived, and some panels were exquisite. But it all awaited ruin. Arches dripped through green-black cracks; the monsoon damp was rotting away plaster; and the sharp smell of bat dung was everywhere.

All vitality had been sucked up into that palace on the hill; and now vitality had gone out of Bundi. It showed in the run-down town on the hillside below the palace; it showed in the fields; it showed in the people, more beaten down than at Kotah Town just sixty miles away, less amenable to the commissioner’s ideas, and more full of complaints. They complained even when they had no cause; and it seemed that they complained because they felt it was expected of them. Their mock aggressiveness and mock desperation held little of real despair or rebellion. It was a ritual show of deference to authority, a demonstration of their complete dependence on authority. The commissioner smiled and listened and heard them all; and their passion faded.

Later we sat with the “village-level workers” in the shade of a small tree in a woman’s yard. These officials were the last in the chain of command; on them much of the success of the scheme depended. There had been evidence during the morning’s tour that they hadn’t all been doing their jobs. But they were not abashed; instead, sitting in a line on a stringbed, dressed not like the peasants that they almost were, but dressed like officials, in trousers and shirts, they spoke of their need for promotion and status. They were far removed from the commissioner’s anxieties, from his vision of what could be done with their land. They were, really, at peace with the world they knew. Like the woman in whose yard we sat. She was friendly, she had dragged out stringbeds for us from her little brick hut; but her manner was slightly supercilious. There was a reason. She was happy, she considered herself blessed. She had had three sons, and she glowed with that achievement.

All the chivalry of Rajasthan had been reduced here to nothing. The palace was empty; the petty wars of princes had been absorbed into legend and could no longer be dated. All that remained was what the visitor could see: small, poor fields, ragged men, huts, monsoon mud. But in that very abjectness lay security. Where the world had shrunk, and ideas of human possibility had become extinct, the world could be seen as complete. Men had retreated to their last, impregnable defenses: their knowledge of who they were, their caste, their karma, their unshakable place in the scheme of things; and this knowledge was like their knowledge of the seasons. Rituals marked the passage of each day; rituals marked every stage of a man’s life. Life itself had been turned to ritual; and everything beyond this complete and sanctified world—where fulfillment came so easily to a man or to a woman—was vain and phantasmal.

Kingdoms, empires, projects like the commissioner’s: they had come and gone. The monuments of ambition and restlessness littered the land, so many of them abandoned or destroyed, so many unfinished, the work of dynasties suddenly supplanted. India taught the vanity of all action; and the visitor could be appalled by the waste, and by all that now appeared to threaten the commissioner’s enterprise.

But to those who embraced its philosophy of distress India also offered an enduring security, its equilibrium, that vision of a world finely balanced that had come to the hero of Mr. Sampath, that “arrangement made by the gods.” Only India, with its great past, its civilization, its philosophy, and its almost holy poverty, offered this truth; India was the truth. So, to Indians, India could detach itself from the rest of the world. The world could be divided into India and non-India. And India, for all its surface terrors, could be proclaimed, without disingenuousness or cruelty, as perfect. Not only by pauper, but by prince.

IV

Consider this prince, in another part of the country, far from the castles of Rajasthan. Another landscape, another type of vegetation; only, the rain continued. The princes of India—their number and variety reflecting to a large extent the chaos that had come to the country with the breakup of the Mughal empire—had lost real power in the British time. Through generations of idle servitude they had grown to specialize only in style. A bogus, extinguishable glamour: in 1947, with Independence, they had lost their states, and Mrs. Gandhi in 1971 had, without much public outcry, abolished their privy purses and titles. The power of this prince had continued; he had become an energetic entrepreneur. But in his own eyes, and in the eyes of those who served him, he remained a prince. And perhaps his grief for his title, and his insistence on his dignity, was the greater because his state had really been quite small, a fief of some hundred square miles, granted three centuries before to an ancestor, a soldier of fortune.

With his buttoned-up Indian tunic, the prince was quite the autocrat at his dinner table, down the middle of which ran an arrangement of chiffon stuck with roses; and it was some time before I saw that he had come down drunk to our teetotal dinner. He said, unprompted, that he was “observing” the crisis of Indian democracy with “interest.” India needed Indian forms of government; India wasn’t one country, but hundreds of little countries. I thought he was building up the case for his own autocratic rule. But his conversational course—almost a soliloquy—was wilder.

“What keeps a country together? Not economics. Love. Love and affection. That’s our Indian way…. You can feed my dog, but he won’t obey you. He’ll obey me. Where’s the economics in that? That’s love and affection…. For twenty-eight years until 1947 I ruled this state. Power of life and death Could have hanged a man and nobody could have done anything to me…. Now they’ve looted my honor, my privilege. I’m nobody. I’m just like everybody else…. Power of life and death. But I can still go out and walk. Nobody’s going to try and kill me like Kennedy. That’s not economics. That’s our love and affection…. Where’s the cruelty you talk about? I tell you, we’re happy in India…. Who’s talking about patriotism? Have no cause to be. Took away everything. Honor, titles, all looted. I’m not a patriot, but I’m an Indian. Go out and talk to the people. They’re poor, but they’re not inhuman, as you say…. You people must leave us alone. You mustn’t come and tell us we’re subhuman. We’re civilized. Are they happy where you come from? Are they happy in England?”

In spite of myself, my irritation was rising. I said: “They’re very happy in England.” He broke off and laughed. But he had spoken seriously. He was acting a little, but he believed everything he said.

His state, or what had been his state, was wretched: just the palace (like a country house, with a garden) and the peasants. The “development” (in which he had invested) hadn’t yet begun to show. In the morning in the rain I saw young child laborers using their hands alone to shovel gravel on to a waterlogged path. Groundnuts were the only source of protein here; but the peasants preferred to sell their crop; and their children were stunted, their minds deformed, serf material already, beyond the reach of education, where that was available.

(But science, a short time later, was to tell me otherwise. From the Indian Express: “New Delhi, Nov. 2…Delivering the Dr. V. N. Patwardhan Prize oration at the India Council of Medical Research yesterday, Dr. Kamala Rao said certain hormonal changes within the body of the malnourished children enabled them to maintain normal body functions…. Only the excess and non-essential parts of the body are affected by malnutrition. Such malnourished children, though small in size, are like “paperback books” which, while retaining all the material of the original, have got rid of the non-essential portion of the bound editions.”)

The prince had traveled outside India. He was in a position to compare what he had seen outside with what he could see of his own state. But the question of comparison did not arise. The world outside India was to be judged by its own standards. India was not to be judged. India was only to be experienced, in the Indian way. And when the prince spoke of the happiness of his people he was not being provocative or backward-looking. As an entrepreneur, almost an industrialist, he saw himself as a benefactor. When he talked about love and affection he did not exaggerate: he needed to be loved as much as he needed to be reverenced. His attachment to his people was real. And his attachment to the land went beyond that.

In the unpopulated, forested hills some miles away from the palace there was an old temple. The temple was small and undistinguished. Its sculptures had weathered to unrecognizable knobs and indentations; the temple tank or reservoir was overgrown and reedy, the wide stone steps had sagged into the milky-green slime. But the temple was important to the prince. His ancestors had adopted the deity of the temple as their own, and the family maintained the priest. It was an ancient site; it had its genius; the whole place was still in worship. India offered the prince not only the proofs of his princehood but also this abiding truth of his relationship to the earth, the universe.

In this ability to separate India from what was not India, the prince was like the middle-class (and possibly rich) girl I met at a Delhi dinner party. She was married to a foreigner and lived abroad. This living abroad was glamorous; when she spoke of it she appeared to be boasting, in the Indian fashion: she detached herself from the rest of India. But for the Indian woman a foreign marriage is seldom a positive act; it is, more usually, an act of despair or confusion. It leads to castelessness, the loss of community, the loss of a place in the world; and few Indians are equipped to cope with that.

Socially and intellectually this girl, outside India, was an innocent. She had no means of assessing her alien society; she lived in a void. She needed India and all its reassurances, and she came back to India whenever she could. India didn’t jar, she said; and then, remembering to boast, she added, “I relate only to my family.”

Such security! In the midst of world change, India, even during this Emergency, was unchanging: to return to India was to return to a knowledge of the world’s deeper order, everything fixed, sanctified, everyone secure. Like a sleepwalker, she moved without disturbance between her two opposed worlds. But surely the streets of Bombay must make some impression? What did she see at the moment of arrival?

She said mystically, blankly, and with truth, “I see people having their being.”

(This is the first part of a two-part article on India. The second will appear in the next issue.)

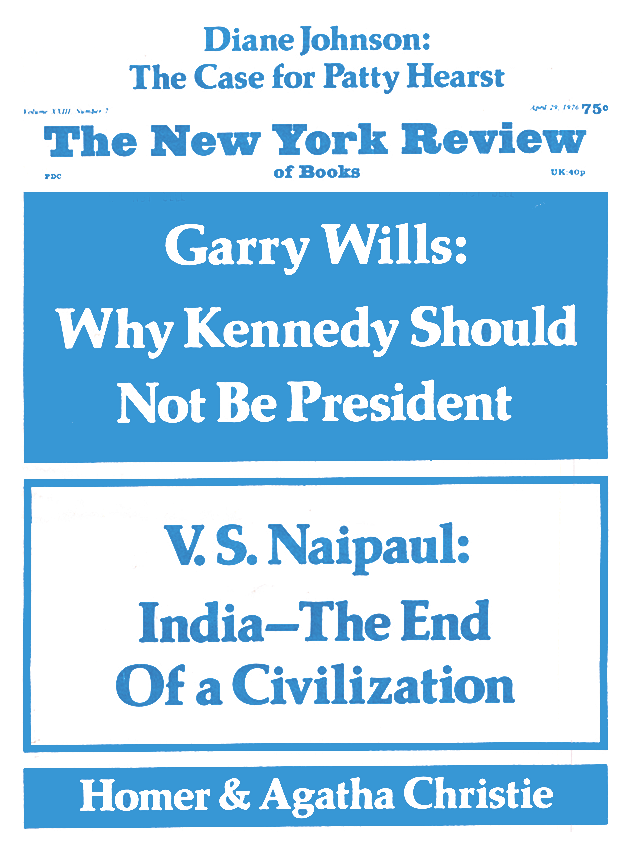

This Issue

April 29, 1976