I

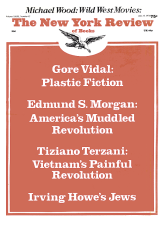

You can change your religion but not your grandfather, said Ludwig Börne, who should have known. This, presumably, is the wisdom prevailing behind the torrents of nostalgia inundating the American Jewish community. When the Jewish Museum a few years ago mounted a lavish exhibition about the lower East Side, droves of college-educated, Bloomingdale’s-outfitted people came to Fifth Avenue to stare dreamily at the photos of pious, bedraggled Jews who looked as if they had come from another planet. More recently the same audience turned Hester Street into the sleeper of the year. But it is mostly in the printed word—Jews will be Jews—that the fashion is to be found. Publishers pour out a profusion of memoirs, novels, studies, and handsome photographic albums that undoubtedly make their way to any number of suburban coffee tables and bewildered Bar-mitzvah boys.

Into this hectic recherche du temps perdu comes Irving Howe’s book. Perhaps its most refreshing strength in this climate of rampant Jewish sentimentality is its utter lack of any. Howe is not one of those uneasy Jews who at the first whiff of herring or flicker of a Sabbath candle break into prose poetry. (His manner recalls Chekhov’s reaction to Tolstoy’s romanticized muzhiks: “There is peasant blood in my veins and you can’t bowl me over with peasant virtues.”) He knows what made his fathers great and what made them small, and his sobriety is itself an eloquent act of homage.

World of Our Fathers, let it be said at once, is a masterly social and cultural history, a vivid, elegiac, and scrupulously documented portrait of a complicated culture, from its heroic beginnings to its unheroic end. Fully conversant with the literature on America’s Jews, Howe has generously supplemented it with the little-known writings of journalists and memoirists, and studded his narrative with those evocative petits faits significatifs without which social history would be only a slightly less dreary branch of sociology. Never once does he lose sight of his hero, dos kleyne menshele, the little man; the compassion in his scholarship has a strong Orwellian ring.1

Beginning in the 1880s, and for several decades following, roughly two million Jews made the perilous journey from the Pale to New York. As Howe depicts it, the most distinctive feature of their life on the lower East Side was its intensity, the seemingly inexhaustible energies realizing and dissipating themselves in those cramped, clamorous streets. There all the pent-up desires of an age-old exile appeared to be finding release, among them many which had had to remain underground in the firmly ordered Jewish society of Eastern Europe. But in the teeming and still formless world of the disembarked immigrants, anything seemed possible, as strangers in a strange land struggled to lift themselves out of their wretchedness, belatedly claiming their share of unexplored experience and expression.

The intellectual vitality of these slum-dwellers was also astonishing. With the Torah and the Talmud they brought Das Kapital and Fathers and Sons. The East Side became an unruly haven of idealisms jostling against one another. This loftiness contrasted starkly with the abysmal conditions of their everyday existence, urban horrors which recall Dickens or Zola, and beneath which many a poor nameless immigrant sank. Therein lay the challenge, the pathos, the tragic flaw of the “world of our fathers”—in this contradiction between high principle and low reality. The experience in America was a moral schooling, an extended bruising lesson in the means and costs of self-betterment. The moral grandeur of many immigrants never came undone, but their children did not quite inherit it. In the tenement contests between the rats and the dreams, neither emerged victorious.

Howe goes into great detail about the trials of the immigrant Jews in New York—the grueling abuses of the sweatshops, the shabby and stinking tenements, the mutilations of family life, the Yiddish demimonde of the East Side (where whores were named Katz and Cohen and hoods called Little Kishky), the spiritual desiccation and religious disillusionment.2 Faced with America’s insatiable individualism, the old communal bonds suffered irreparable damage.3 In such a world of anomic darkness, the community threatened on all sides by breakdown and dispersion, dazed Jews sorely needed an explanation and a plan of action—in a word, an ideology. On the East Side that was not hard to come by.

The Orthodox, those perennial experts at producing reasons, counseled faith and patience.4 Zionists promoted their own analysis of the Jewish problem, but on the East Side without much success. Their failure to take hold among the immigrants indicates that an attitude fundamental to their received world view, the distinction between the Diaspora and an ideal Jewish autonomy, was being undermined. Zionism was dismissed because most had concluded that they no longer had to expect displacement, that their problem must be solved in America. The Jews trusted America—“our Zion,” one rashly called it—and dared to hope that for them happiness was at last a workable proposition.5 This hope engendered an ostensibly un-Jewish reluctance to defer their happiness any longer, or in the name of some vast historical plan which only discloses itself to victims. And this reluctance proved decisive for the fate of the Jewish community for many years to come. It became the Achilles heel of Jewish socialism, and the ruin of many parents’ dreams.

Advertisement

Large numbers of this immigrant proletariat turned above all to socialism. Gradually they realized that effective and large-scale relief would come only by the fierce efforts of a combative working class alive to its own interests. “The 70,000 zeroes became 70,000 fighters,” said the Yiddish poet Liessen after the dramatic strikes of 1909, the anno mirabilis of Jewish socialism in America.

Of course Judaism had much in common with socialism, notably that prophetic messianism which, we are forever reminded, survives in Marx. More important, the socialism of the East Side was deeply colored by the idioms and imagery of its Jewish rank-and-file—one cleaners’ union on Henry Street ended its meetings with dancing to Hasidic tunes; Abraham Cahan, “Der Proletarisher Magid” (the proletarian preacher), heaped “elaborate Vilna curses” upon the wealthy, including uptown German Jews. This was a working class drenched in Jewish tradition—“if a rabbi dies even the heretics weep”—and no socialism at war with that tradition could ever win their loyalties. The anarchists who combined exalted revolutionary fervor with ferocious attacks on religion—such as giving balls on Yom Kippur—were bound to fail.

Irving Howe’s engagement with his subject is nowhere more intense than in his treatment of Jewish socialism, which he sees as “primarily a political movement dedicated to building a new society; part of a great international upsurge that began in the nineteenth century and continued into the twentieth.” This is certainly true of its inception and early history; it is also what Howe, the editor of Dissent, and himself a socialist distressed by the demise of this tradition among his fellow Jews, would wish them to see. But as a description of socialism’s career in the American Jewish community it misses its mark.

Much more urgent for the Jewish unions than a revolutionary new society was relief in the society they knew. They later took enthusiastically to the New Deal because it reflected their style of social action, in which effectiveness took precedence over ideology. Led by shrewd organizers such as David Dubinsky, men better equipped for the subtleties of the bargaining table than the finer points of Plekhanov, they were not averse to being absorbed into the political process if that would aid in ameliorating the conditions of workers’ lives. In this respect they differed enormously from so much of nineteenth- and early twentieth-century socialism, and seem closer in spirit to some of the leftist opposition parties in Europe today.

“The most fascinating characteristic of the immigrant Jewish workers,” writes Howe, “[was] that many of them should be simultaneously inflamed with revolutionary ideas and driven by hopes for personal success and middle-class status.” But the two were incompatible, and the less elevated aims triumphed. The Jewish workers adjusted their vision to more tangible ends; these finally attained, they abandoned their revolutionary attitudes. Historians of the movement such as Daniel Bell and Will Herberg conclude that Jewish socialism was primarily a process of integration into American life, and they are right. As Howe himself ruefully notes:

Jewish socialism gradually transformed itself from a politics into a sentiment—a sentiment tended with affection and respect but no longer from the premise that the will or heroism of an immigrant generation could change the world.

The contradiction between vision and ambition which divided socialism against itself was played out in many households, where the fathers dreamed of a better and more just world, but were equally fervent in their wishes to improve the lot of their children. They wanted their sons to carry on the traditions of Jewishness, but they also wanted them to become at ease in America. They could not have it both ways. For the sons to get on in America they would have to enter precincts of consciousness and experience far beyond the culture of their childhood, whose social idealism and religious devotion were irreconcilable with their own careers. These immigrant parents thundered, they regretted, they looked away—but they saw their sons through law and medical schools and into affluent America.6 “In behalf of its sons,” Howe concludes, “the East Side was prepared to commit suicide; perhaps it did.”

Accustomed as we are to hearing about the essential affinity between Jewish ethics and revolutionary ideals, it might seem surprising, and a failure of moral will, that the Jewish socialists of America turned away from the struggle for an altered world. But their response also has its roots in the Jewish tradition, roots which perhaps run deeper than those the radicals acknowledge. The Torah commands the Jew to aid the poor, the widow, and the orphan as he encounters them—not to postpone his aid until the ideologically correct moment beckons. As against the patience with which the Jew must await the Messiah, there is the indignation that he must feel at each meeting with suffering, an indignation that only immediate charity and assistance can mollify. But when in 1926 rebellious communists in the garment center behaved in utter disregard of the misery they were raining upon the workers in their bid for power, the Jewish unions summarily banished them. Misery caused in the name of misery’s end is just more misery. The intelligent Hayim Greenberg spoke for this humane Jewish skepticism in his essay on Trotsky:

Advertisement

If Trotsky and Stalin are typical of revolutionary salvationists, if those who undertake to redeem humanity bear within themselves such volcanoes of hate, brutality, and criminality…then social redemption is a curse. Perhaps we should no longer laugh at the Jewish village woman who, when her husband told her that the Messiah was about to come in a few days, exclaimed that the God who had saved us from Pharaoh and Haman…would have mercy and save us from the Messiah’s hands.

There were other, less political responses to the encroaching decomposition of the Jewish community. A vigorous culture flourished on the East Side, as premodern in its cohesiveness as it was modern in its omnivorous appetites, a culture of Yiddish reflecting its mercurial mixture of edelkeit and vulgarity.

Rarely has journalism had such a strong and unifying impact upon a culture; if, as Maurice Samuel touchingly put it, “the Bible was a daily newspaper” in the shtetl, it was no less true that the daily newspaper was a Bible on the East Side. The Yiddish theater was its ritual heart throb. But the indigenous nature of Yiddish culture is nowhere more apparent than in its poets. On the East Side, as Howe says, there were only “proletarian esthetes, Parnassians of the sweatshop.” Mani Leib wrote that “I’m not a cobbler who writes, thank Heaven, / But a poet, who makes shoes.” As late as 1934, when his verse and plays had already been translated into many languages, the nocturnal visionary poet Leivick could still be seen carrying his paint bucket and wallpaper through the streets.

The poets, in short, shared the fate of the people. But if this gave them an intimacy with their audience which other modern poets did not have, it also meant that the self-conscious detachment and complexity of modern poetry was impossible. Nuances of sensibility or temperament could not break through the shared tribulations. The earliest poets of the 1880s, “sweatshop poets” like Morris Rosenfeld, had sung only of common woe, and never in the first person. One critic dubbed them “the rhyme department of the Jewish labor movement.” But, as Howe contends, even later poets who felt the liberating influence of modernism—and there were many—could never achieve or sustain the autonomous voice they sought.

As they struggled to overcome the limitations of what Yeats once approvingly referred to as “the emotion of multitude,” the tradition of Yiddish poetry was being subverted elsewhere. Instead of Mani Leib or Leivick, the younger generation read Eliot and Pound. Children returning from college had little interest in Yiddish culture, which didn’t stand a chance against the variety of American life.

The theater, the poets, the prose writers were forgotten—except for Isaac Bashevis Singer, who has his foot in both doors—and left no followers. Jacob Glatstein, the dominant figure of the In Zikh or “introspectivist” group which tried to absorb the poetic techniques of Pound, Eliot, Stevens, and H.D., memorably expressed his bitterness to Howe this way: “What does it mean to be a poet of an abandoned culture? It means that I have to be aware of Auden but Auden need never have heard of me.” The destruction by the Nazis of Yiddish culture in the old country dealt the final blow. As the political solidarity of the Jewish workers has hastened its own breakdown, so too had Yiddish culture sped toward its own obsolescence. It had survived the journey to Manhattan, but would not make it to Long Island. Howe, a fine translator from the Yiddish himself, offers no hope for its revival.

II

In the preface to his instructive new book, the historian of immigration John Higham writes:

Ethnic history tends to be highly particularistic. Every group naturally wants to know its own special story and little more…. The acid test of any history, ethnic or otherwise, is the historian’s ability to penetrate situations and mentalities remote from his own. The notion that only one who belongs to a group can understand and therefore do justice to its past is profoundly destructive of the historian’s calling.7

Irving Howe is certainly no mere laudator temporis acti. His book is not entirely locked into the premises of the immigrant experience. Nonetheless, as one reads his intelligent narrative, the same questions recur. How much was this unique to the Jews? And if much of it was not, then what in fact distinguished the Jewish immigrant experience from others? Howe does not really address these questions, nor do they tend to get asked from within the ethnic bubble.

The million or so Italian contadini who swarmed into New York with the Jews certainly fared no better there. They too lived in decayed surroundings, slaved in sweatshops, watched their ancient families disintegrate. Young Italians were as fired by the American promise as young Jews. As Jews lapsed from Judaism, so did Italians lapse from Catholicism; in both cases orthodox observance was generally frittered away into folk custom. It would, then, be unwise to claim for Jews a monopoly on such troubles—as unwise, I hasten to add, as it would be to deny the Jews the macabre monopoly on certain forms of suffering which they endured, for example, in the Second World War.

Still, there are significant differences between Jewish immigrants and others—differences, above all, in the Jewish response to the hardships all shared. An Italian immigrant reminiscing in 1920 had this to say about his motivations in coming to America:

If I am frank, then I shall say that I left Italy and came to America for the sole purpose of making money…. I suffered no political oppression in Italy…. That is true of most Italian emigrants to America….

But it is not true of most Jewish emigrants to America. However crippling the poverty of the shtetl, however menacing the slow infiltration into it of Western enlightenment, sheer physical survival induced the Jews to leave. They fled from the Czar’s Black Hundreds, from savage pogroms and systematic persecution.

Other immigrants were still Christians coming to a Christian country. The coolness which Italians felt toward the Irish-dominated Catholic institutions of America was not quite the alienation of Jews who knew that they were, after all, still in a kingdom of goyim. This meant, at least from the Jewish point of view, that Jewish fears were greater and their insecurities more numerous. To become part of the culture seemed to require renouncing all. An Italian or Irish salesman might still find an acceptable Sunday church in Topeka, but a Jew then traveling into America would probably have to give up shul altogether. “The very clothes I wore and the very food I ate had a fatal effect on my religious habits,” said David Levinsky, the parvenu hero of Abraham Cahan’s searching novel about the high personal costs of immigrant success in America.

Finally, there was the problem of anti-Semitism in America, which Howe treats sketchily. The record on anti-Semitism is by all accounts a benign one. The French anti-Semitic writer and agitator Eduard Drumont may have altered the course of French politics for decades, but who in America remembers his contemporary, Telemachus Timayenis? There was never an organized anti-Semitic movement in the United States, like the anti-Catholic American Protective Association. Nativist prejudice was usually directed against all immigrants equally, and, in cases like San Francisco, where it was not, the presence of other groups (in this case the Orientals) took the heat off the Jews. This was largely true of the South as well; the Jews were at least white. Nor were Jews ever targets of mob violence as Italians were, who were for years suspected of being a nation of seditious anarchists. As John Higham has shown, the American has always been of two minds about the Jew—for the religious American he was as much the portentous agent of God’s providence as the deserving victim of His punishment; for the more this-worldly American, he was as much a paragon of capitalist resourcefulness as a despicable Shylock.

Of course there was—and is—anti-Semitism in America. Agrarian radicals in the Populist movement of the late nineteenth century ranted about international Jewish conspiracies. The Ku Klux Klan and Henry Ford’s infamous Dearborn Independent spewed out racist tripe. In Boston a self-pitying Henry Adams vented his offended patrician pride against “450,000 Jews now doing Kosher in New York,” none of whom he ever actually met.8 Yet these demonstrations of anti-Jewish feeling were important not for their real consequences, which by European standards were negligible, but precisely because they mattered to the Jews themselves.

These Jews were venturing into America with what Lewis Namier described as “the consciousness that we cannot afford to slip [because] a fall for us is harder and more irretrievable than for a non-Jew.” They were certain that above the Jew there is never a cloudless sky, a misgiving from which other immigrants were far more free. Perhaps the Jews were often overreacting—but they were seeing themselves in the way their tradition and history taught them to comprehend their lives. Coming to America in the hope that there the grim pattern of Jewish history would finally be disrupted, they were still prepared to learn that once again it would not be. What distinguished the Jews from other immigrants, then, was their image of themselves, however morbid or self-elected that was. They differed in believing that they differed, that their fate was blighted in ways that others’ was not.

Some historians of the Jews—such as those for whom a cigar is never a cigar—overlook, in their search for hidden causes, the actual experience and perceptions of the Jews they study. But Howe often, and not uncritically, lets the immigrants speak for them-selves. Indeed no historian who fails to deal with the deeply ingrained self-image of the Jews will ever understand them. It can be fairly argued that Jews have always relied more heavily upon communal introspection than have other peoples, that Jewishness has always been a form of consciousness. Deprived for so long of the outward signs of community—of a single language and a homeland—which for others were reliable and unremarkable confirmations of their membership in a polity and culture, the Jews were forced to turn inward for such confirmations and find them in what they believed about themselves.

What was unprecedented in Jewish history about the American immigration—so one could conclude from. Howe’s narrative—was the confrontation between the view of the world Jews brought and that which they found, the precise way in which America revised the “ghetto mentality.” What America really provided was a new way for Jews to perceive themselves; and what changed above all was the most basic feature of their world picture, the distinction between Jew and non-Jew, Jew and goy. More abstractly, I mean the tension between universalism and particularism in the Jews’ appraisal of where they stood.

The history of Jewish identity could be written about that tension, which is itself written into the Jewish tradition from its very beginnings. The God who singled out the Jews to “dwell alone and…not be reckoned among the nations” was the same God who commanded his prophets to agitate for universal peace and justice. In the medieval world, when every people and faith drew mankind narrowly in its own image, there was little opportunity for displays of cosmopolitanism, particularly by hounded and sequestered Jews. But being forced to live on the margin could also lead many of them to cultivate a pronounced humaneness, and when the eighteenth century proposed the ideal of a humanity which transcended parochialism and prejudice, of a collaboration of rational men everywhere dedicated to the improvement of the human condition itself, the latent universalism among the Jews sprang to life—so much so that, as Howe and others have observed, universalism became a perverse kind of Jewish parochialism.

From the high-minded Reform Jews of Germany to the revolutionaries of Petrograd and Berlin, many Jews sought to make the common lot their first priority. Such altruism could at times reach feverish proportions, as self-sacrifice veered into self-hatred; “there is no room in my heart for the Jewish troubles,” wrote Rosa Luxemburg. In the United States, too, internationalist Jewish radicals ignored the Kishinev pogrom of 1903 because it could not be tidily worked into their class analysis of the cosmos, and Jewish Communists responded to the 1929 massacre of Jewish students in Palestine by hailing its Arab perpetrators as “fighters for national liberation.” The phenomenon is still with us.

Both universalism and particularism, however, had one thing in common as assessments of the Jew’s place in history—the conviction that he was at its center, the unique agent or victim of its design. The separatists of the besieged Orthodox camp, the Reform Jews who spoke about a Jewish mission to the world, the Socialists who looked to the prophets for their ultimate moral authority, even Kafka for whom Jewish pain was the modern anguish in purest form—all these still held to some version of the view that by virtue of faith or suffering the Jew was unique, possessed of a special vantage point on the world. Some were fortified by this feeling in their struggle to remain apart from the secularized world, others found in it their creative and critical edge.

The American melting pot was supposed to exert its own universalistic pressure, leveling the social and cultural irregularities of immigrants and bringing all under a single homogeneous American description, an abstract, unclarified, but binding equivalence somewhat on the order of the French citoyen. The popularity of the “Melting Pot” idea owed much to a drama of the name by a British Jew, Israel Zangwill, but as early as 1915 another Jew, Horace Kallen, was formulating a more apposite American ideal of “pluralism.” Most simply, pluralism means democratic individualism for groups. The melting pot was undemocratic, argued Kallen, because it was opposed to the distinctiveness of its diverse ingredients. Instead Kallen envisaged “a cooperative of cultural diversities, a federation or commonwealth of national cultures.” Kallen’s proposal was in the first place more realistic, reflecting the growingly apparent incompleteness of immigrant acculturation in America. But it had the added and unheard-of advantage for Jews of being a social philosophy which frowned upon assimilation and gave to traditional loyalties pride of place. Pluralism’s extraordinary promise to Jews was of an accommodation that was not self-effacing, an improvement in the conditions of Jewish life which would not demand severe inward dislocation as its price.9

On the pluralist model it seemed as if the Jew could finally have his kosher cake and eat it too, as if the unholy—some Jews would say sacred—alliance between Jewishness and misery was at last coming to an end. Certainly a kind of pluralism became acceptable for American city governments, school systems, textbooks. And in such an America the Jews did indeed achieve the “normal life” that had always eluded them, and they did so in most cases without that pariah consciousness which had soured their acceptances elsewhere. But, as Howe acknowledges, there was still a price to be paid. The absolute significance which Jews had customarily attached to their fate, that urgency which both universalists and particularists could impart to Jewish life, was not possible in a situation for which the Jewish difference could be little more than anthropological. The Jews in America may be important to numerous aspects of American life, but they can no longer claim even to themselves that they are intrinsically at its center.

Nor, for that matter, could anti-Semites. In a pluralist society Jewish influence, however great, could clearly not explain everything. (Much more persuasive to native Americans would be charges of immigrant influence in general.) The old anti-Semitic accusation that Jews constituted a rapacious “state within a state” could not really catch on in America: was not nearly every group in the United States just such an imperium in imperio? Ever since Amalek attacked them on the other side of the Red Sea, the Jewish obsession with chosenness has owed as much to necessity as to choice; their perennial enemies had certainly singled them out for something. America, however, was the kind of place where Jews would “suffer of malaise and not of persecution,” as Namier put it.

It was inevitable that the pluralist scenario would lead each of the immigrant groups to see itself as never more than one among many. And while this relativism was certainly an overdue form of tolerance, it could only relax the tempo of Jewish life and curtail Jewish self-expectations. Naturally there remained Jews who still aimed at intellectual and cultural heights, but among the masses themselves their parents’ unslackened idealism and respect for such achievement all but disappeared. Jewish life in America became less exigent as it became less marginal—or rather as it came to rest in that distributed marginality which everyone in America shared. Hank Greenberg and Sid Caesar became as integral to Jewish culture and pride as Morris Raphael Cohen and Saul Bellow.

What complicated the distinction between Jew and goy in America was not merely the inescapable fact that Jews and goyim usually spoke, dressed, and behaved in the same way—this had been the case before elsewhere. Rather it was that the blunt traces of Jewishness which survived in the manners of American Jews—the Jewish difference itself—could no longer find legitimacy in the Jewishness of the European past, but neither was America requiring their eradication. Indeed, by a strange and very American irony, being Jewish—that is, aligning one’s self with the traditions of one’s parents—became a way of being like the goyim, who also lived according to the pluralist ideal of ancestral loyalties. Thus, in the 1960s, for instance, Jewish youth could learn as much about collective self-respect and self-assertion from the black example as from the Six-Day War. Cut off from both idealism and suffering, Jewish idiosyncracies seemed arbitrary and even fatuous. The febrile responses of Lenny Bruce, Philip Roth, and Leslie Fiedler—among others—all reflect a deep uneasiness about this arbitrariness.10

III

The melting pot, as we all know, did not work. Jews discovered that they could not will themselves entirely out of their origins, and that such denials were pathologies of the spirit. “I cannot escape from my old self,” lamented David Levinsky, and neither could most Jews raised in the Jewish community before its fall. But more striking are the lingering loyalties of their children. Even these native Americans born, in Harold Rosenberg’s phrase, “with at least as much anonymity as Jewishness,” could not slake off their Jewishness entirely. In New York, where Jews and Jewish manners were ubiquitous, it was easy enough for Jews to feel estranged from other Jews. In the suburbs, however, where no such cushion for the feelings existed, discomfited Jews discovered that they would have to decide whether or not to declare themselves as Jews. The proximity of non-Jewish neighbors made them acutely conscious of being different.

Most declared for Jewishness. For all the obliviousness of these assimilated children to the world of their fathers—“practiced nonchalance,” as Disraeli once said of a similar Jewish attitude of his day—they nonetheless moved in social circles that were exclusively Jewish, formed a local temple, sent their children to Hebrew school. “I don’t want my children to get too much religious training,” one said, “just enough to know what religion they’re not observing. After all, if gentiles know about it, so should Jews.” Of course this was a highly attenuated Jewishness, a phantom of what came before. (Orthodox Jews who furnish separate schools for their children and forbid them to go to college know just what they are doing, though not how futile their resistance is.) But it would be unfair to dismiss such choices for that reason as fraudulent, or as just another instance of suburban banality. For these Jews, malgré eux, Jewishness had become what it had been for many Jews in Europe since the Emancipation—a question of personal honor.

These days a new version of the pluralist idea is taking hold among American Jews, one which Howe’s book, in spite of itself, will be recruited to support. This is the fashionable notion of ethnicity, whose popularity certainly owes much to the success of the black style in politics and pride. Some now want to see New York simply as a collection of neighborhoods, the more insular and colorful the better—ubi domus ibi patria. This sentiment in the streets is meanwhile endorsed by many distinguished sociologists, not to mention politicians. Jimmy Carter blunders ingeniously about “ethnic purity,” and Gerald Ford retorts by mumbling something about “ethnic treasure.” The enthusiastic revival of interest in immigrant Jewish culture is certainly part of this larger ethnic boom.

Why such flexings of Jewish ethnicity now? Partly because everybody else is doing it, because ethnic is beautiful. Partly too because the increasing isolation of Israel in the face of unprecedented Arab influence is bringing Jews together, almost in the way anti-Semitism does. And partly because the third generation can look back most painlessly. Jews like Budd Schulberg’s renegade Sammy Glick are hardly the stuff of which nostalgia is made. “We carry our fathers on our backs,” said his contemporary Delmore Schwartz.

But the widespread eagerness with which ethnic identities are now embraced has deeper reasons. It suggests a wish to revert to a simpler and more Arcadian time. For Jews exhausted by their own fragmented and increasingly invisible Jewishness, who seek to unburden themselves of an identity too nuanced to work, memories of the hale Jewishness of their ancestors can have a compensatory, even narcotic, effect.11 Some Jews speak sweetly of New York’s neighborhoods as if they were shtetlekh in miniature, where Jewish life is rosy and the Jewish community yet intact. But life in the shtetl, not to mention life on the lower East Side, was not the rounded and radiant affair they would like it to have been. And neither is life in Bensonhurst or Brighton Beach. As Howe writes, “We cannot be our fathers.”

There are other things wrong with ethnicity as well. It should be obvious that pluralism is far from the whole truth about America. The ethnic appraisal of cultural and national traditions is often very superficial, confining itself to quaint surfaces and easily mimicable mannerisms; a few knishes here, a little pasta there. For the votaries of ethnicity all folkways are in the end equally valuable, all equally edifying, because all are nourished by that splendid élan vital animating each group. Such attitudes, furthermore, are themselves mostly fed by stereotypes, however spurious or implausible, and themselves spawn new myths with which to clutter consciousness. Mrs. Portnoy is about as typical of most Jewish mothers as Corleone is of most Italian fathers.

“Ethnicity,” in short, disarms self-criticism. Often it inculcates an alarming self-righteousness about what is peculiar to one’s own community. At bottom ethnicity is nothing other than our modern ethic of authenticity writ large, applied to groups and the conscience collective. But authenticity—and the almost exhibitionist passion for self-revelation which follows in its train—is as a moral ideal deeply flawed. It is usually just a rarefied pretext for self-satisfaction, as much on the part of groups as of individuals.

When immigrants’ children strove fervently to divest themselves of all vestiges of die alte heym, to repress the memory of their Eastern European fathers and the harsh demands of their culture, they sometimes lied about the past, and changed their names, their speech patterns, their modes of behavior. Assimilation meant inauthenticity. But, as Howe shows, the repression was cruelly incomplete, the dreaded ghosts could not be dodged and the guilt not escaped. Many first and second-generation immigrants died with tarnished consciences, unreconciled to their own origins.

Now the grandchildren are unearthing the censored past. Instead of the bad faith of the alrightnik, the Jewish authentics seek a more dignified and affirmative relation to their roots. But they have yet to show that this rapturous return of the repressed is not the subtlest self-deception and most sophisticated bad faith of all. This they could do only by acting upon their passion, by applying the legacy of the East Side to the problems besetting their community.

In other words, what real difference for the Jews will the present revival make? How many Jews will provide their children with some kind of serious Jewish education because of it? How many will contribute time and money to help relieve the 350,000 Jews, many of them aged and helpless, now languishing at or below the poverty level? How many will help to rescue Yiddish and its world before it disappears completely? Who will recover the ethical and political position from which to goad a sluggish and concupiscent community into reflection?

Indeed, Howe has himself undertaken to do so, arguing for unrestrained discussion among American Jews of Israeli policy. Concerned by attempts to muffle the dissenting opinions of, among others, the Israeli dove Arie Eliav and the American organization BREIRA, which sponsored his tour in the US, Howe has recently warned that such attempts

would initiate—or maintain—an atmosphere of conformity and complacence in the Jewish world. It would mean the abandonment of that rich tradition of internal debate (far, far sharper, and far, far livelier than anything BREIRA dreams of) that prevailed in immigrant Jewish life during the early years of the century. It would mean that some Jewish opinions, the official ones, would be Kosher while other Jewish opinions, those of Arie Eliav and Major General Mattityahu Peled, perhaps of other doves closer to or even within the Israeli government, would be treif.12

However one feels about the specific occasion for Howe’s remarks—and he himself fairly notes that the responsibility for seeking to muzzle dovish protest can hardly be placed at the door of the entire American Jewish community—his intentions here are certainly admirable. Such is the spirit of his entire book, which is itself in the best spirit of the immigrant tradition.

I am not quarreling with ethnic self-interest as such, merely the kind of ethnic self-interest which does not take itself seriously enough—which is only an elaborate sop to insincere consciences. And certainly in the checkered sphere of ethnic politics a naïve universalism would be suicide. (Though, again, not all of politics is ethnic.) My complaint is with the present Jewish community itself, with the fact that American Jews have yet to develop an American Jewishness worthy of their talents and resources. To do so they will need more than the cosset of memory. No tree ever grew that was all roots, just as none ever grew without any. For anyone who has even faintly experienced the largesse of traditional Judaism, or the comparable largesse of certain forms of alienation from it, an identity drafted solely along current ethnic lines would be a very paltry Jewishness indeed.

But such a largesse belonged to the immigrant adventure as well, and is still available—though not for too much longer—to a Jewish community that needs all the moral energy it can get. Howe concludes his book with a thoughtful evaluation of the immigrant legacy. He writes of menschlichkeit and Yiddishkeit, of a moral order unmastered by adversity, of selflessness and fraternity and a seriousness about life. But all this is a far cry from the present Jewish community, which is run by a well-oiled collusion of philanthropists and bureaucrats dedicated above all to efficiency and the intrigues of internal community politics. The Jews have been at least as receptive to America’s worst as to its best.

Of course there are people in whom the East Side’s restless intellectual passion and unflagging moral concern still survive, men such as Irving Howe and Meyer Schapiro and Sidney Morgenbesser, but they are pitiably few. There has, too, been movement in recent years among dissatisfied Jewish youth—from gifted student-activists to the more dubious Hare Mishna variety—but all not without a certain modishness and discouraging emphasis on the aesthetic. The world of our fathers was a doomed world and it died. Whether their descendants can overcome complacence and reform their own world remains to be seen.

This Issue

July 15, 1976

-

1

Howe’s book is also a welcome addition to the meager number of studies of the subject available in English. Moses Rischin’s The Promised City: New York’s Jews. 1870-1914 (Harvard University Press) is an excellent and meticulous book, and Hutchins Hapgood’s The Spirit of the Ghetto (1902; Schocken) is as exhilarating as ever. A superb general study of American Jewry is, of course, Nathan Glazer’s American Judaism. On the Jewish world of Eastern Europe which the immigrants left behind, there is Lucy Dawidowicz’s unrivaled anthology The Golden Tradition (Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1967). ↩

-

2

Howe is particularly good on the plight of the Jewish woman—contrary to one reviewer who seemed interested in nothing else—and his discussion of the Jewish mother is a passage of almost sublime decency. On the religious disillusionment: in 1893 one Rabbi Hayim Vidrowitz arrived in New York from Moscow and proceeded to hang a sign out his window which read “Chief Rabbi of America”; when asked by whose authority, he replied: “The sign painter.” Such cynicism was no comfort to the beleaguered immigrants, and contributed to the emergence of that unattractive creature, the American rabbi. ↩

-

3

The best account I know of the effects of American freedom upon Jewish identity is Harold Rosenberg’s magnificent essay “Jewish Identity in an Open Society,” included in his Discovering the Present (University of Chicago Press, 1973). ↩

-

4

Howe’s somewhat perfunctory portrait of immigrant Orthodoxy needs some filling in. The Jews who came to America were, as the sociologist Charles Liebman observed, more secularized than many historians have realized, and their Orthodoxy more of a cultural defense than a religious movement. For many of the great Orthodox rabbis of Eastern Europe America was treif, and they discouraged the pious from immigrating. Those who came were often the least traditional, or worse; Jewish education and other religious essentials were conspicuously neglected upon arrival. It was not until the 1940s that the dominant figures of Eastern European Orthodoxy came to the United States—as did thousands of Orthodox refugees from Hitler’s Europe—and it was then and in the years following that Orthodoxy grew into a formidable religious movement. ↩

-

5

The Zionist leader Shmarya Levin once told Lewis Namier: “Before 1914 a couple of million Jews went to America, a mighty stream; but each of them thought only about himself or his family. A few thousand went to Palestine, a mere trickle; but everyone of them was thinking about the future of our nation.” See the useful discussion in American Jews and the Zionist Idea by Naomi W. Cohen (Ktav, 1975). ↩

-

6

The commonly held misconception that in America Jews rose meteorically and straight to the top should be put to rest. Pace General Brown, Jews never made it to the centers of economic power in the United States, and, as Jerold Auerbach’s recent book Unequal Justice: Lawyers and Social Change in Modern America (Oxford University Press, 1975) shows, their careers in the law profession, for instance, were for many years hindered by an institutionalized anti-Semitism. ↩

-

7

Send These to Me: Jews and Other Immigrants in Urban America (Atheneum, New York, 1975), p. ix. Higham goes on about his own work: “I have sought to demonstrate that a general historian of English descent, possessing only a distant sense of affiliation with the immigrant experience, can nevertheless feel its animating spirit”; this he has indeed shown. The issues of method which Higham raises are troubling ones. While his caveats are appropriate, I think it arguable that the work of a historian who belongs to the group he studies can have an empathetic understanding and an added authority which others might not, and which are not inimical to objectivity; this is certainly the case with Howe’s book. ↩

-

8

Henry James is often lumped together with Adams in this connection, but unfairly. James, for one thing, insisted that “one can speak only of what one has seen,” and visited the lower East Side to see for himself. The feelings of ambivalence and dispossession which he candidly recorded in The American Scene are not anti-Semitic; they are, rather, the dismay of a returning native at the realization that the idea of America was ultimately incompatible with the America he had known. ↩

-

9

A superb discussion of the idea of pluralism is Higham’s “Ethnic Pluralism in American Thought,” in Send These to Me. On universalism, particularism, pluralism, and any number of Jewish fixations, see Milton Himmelfarb’s The Jews of Modernity (Basic Books, 1973), which in many ways is the most remarkable book about Jews that has appeared in many years. ↩

-

10

I thank Jonathan Wilson, of St. Catherine’s College, Oxford, for his help with these ideas, and others in this essay. ↩

-

11

E.g., Sandor Himmelstein in Herzog: “‘Well, when you suffer, you really suffer. You’re a real, genuine old Jewish type that digs the emotions. I’ll give you that. I understand it. I grew up on Sangamon Street, remember, when a Jew was still a Jew. I know about suffering—we’re on the same identical network . We’ll live it up. We’ll find an orthodox shul—enough of this Temple junk. You and me—we’ll track down a good chazan ’ Forming his lips so that the almost invisible moustache thinly appeared, Sandor began to sing. ‘Mi pnei chatoenu golino m’artzenu.’ And for our sins we were exiled from our land. ‘You and me, a pair of old-time Jews.’ He held Moses with his dew-green eyes. ‘You’re my boy. My innocent kind-hearted boy.’ “ ↩

-

12

Howe’s full statement appears in the June issue of Interchange: a monthly review of issues facing Israel and the Diaspora, published by BREIRA. ↩