To the Editors:

Leonard Schapiro has contributed much to Western scholarship on twentieth-century Russian history and politics. I am honored by the attention he devoted to my book, The Bolsheviks Come to Power (NYR, March 31), and grateful for his praise. Still, I would like to erase a false impression about the central focus of my book that his review may have conveyed and also to clarify differences in our interpretations of the revolution, which may have been left somewhat blurred.

Professor Schapiro writes that The Bolsheviks Come to Power is “largely concerned with the way in which Lenin maneuvered his supporters in the capital in order to achieve what he wanted, rather than what they believed was happening.” To the contrary, the major impetus behind my investigation was the conviction that in previous works on the Bolshevik Party in the revolution relatively too much attention had been devoted to Lenin and high-level Bolshevik politics, almost to the exclusion of concern with the independent behavior of lower party bodies and the role of the Petrograd masses in political events of the time. As I explained in the introduction, my primary aim was “to reconstruct, as fully and accurately as possible, the development of the ‘revolution from below’ and the outlook, activity, and situation of the Bolshevik party organization in Petrograd at all levels.” In the process, I tried to clarify the relationship between these two aspects of the revolution and the eventual Bolshevik success.

A main theme of my book is that the Bolsheviks won out in the struggle for power in 1917 Petrograd in large part because their chief goals (as the masses and most party members understood them)—transfer of state power to a democratic, exclusively socialist Soviet government, immediate peace, etc.—corresponded to popular aspirations; at the same time the Provisional Government and the Moderate Socialist Soviet leadership had become widely discredited because of their support of the war effort and delays in the promulgation of meaningful internal reform.

Another major theme is that a key factor in the phenomenal Bolshevik success lay in the nature of the party in 1917. Here I had in mind neither Lenin’s bold and determined leadership, the immense historical significance of which cannot be denied, nor the Bolsheviks’ proverbial, though vastly exaggerated, organizational unity and discipline. Rather, I emphasized the party’s internally relatively democratic, tolerant, and decentralized structure and method of operation, as well as its essentially open and mass character—in striking contrast to the traditional Leninist model. On a number of occasions Lenin issued directives which, if followed to the letter, might well have been disastrous. Each time lower party committees and Bolshevik leaders on the spot, responsive to mass public opinion and fully attuned to rapidly fluctuating political realities, either rejected Lenin’s instructions outright or adapted them to fit the prevailing circumstances. This occurred in October. Had it been otherwise, the Bolsheviks might well not have succeeded. Seen from this perspective, the October revolution in Petrograd was in large part a genuine expression of popular forces, as much a complex political struggle as a military contest, in which the fate of the Provisional Government, though not the precise composition and character of the new Soviet regime, was sealed before the belated coup d’état of October 24-25.

Whether Professor Schapiro is right in implying that The Bolsheviks Come to Power does not throw new real light on the main events of 1917 must be left for readers to decide. I do not agree with the suggestion in his review that serious Western scholars have not tended to view the October revolution as an historical accident or, more frequently, as the result of a well-executed coup (lacking significant mass support) by an essentially united, authoritarian, conspiratorial organization effectively controlled by Lenin. In this connection, it is enough to recall that the late, distinguished Harvard scholar Merle Fainsod was one of a number of influential Western writers who put decisive emphasis on Leninist organizational principles and a carefully planned military conspiracy in explaining the Bolshevik success. As Professor Fainsod summed up the matter in his classic text How Russia Is Ruled:

In 1902 in What Is To Be Done? Lenin had written, “Give us an organization of revolutionaries and we shall overturn the whole of Russia!” On November 7, 1917…the wish was fulfilled and the deed accomplished.

Still, this is not the central issue. For the fact is that even Professor Schapiro, who has for years taken into account that by the fall of 1917 the Petrograd Bolsheviks had substantial popular support, nonetheless generally depicts the overthrow of the Provisional Government as an effectively “camouflaged” “military coup d’état,” divorced from the revolution from below. In this view, the Provisional Government is perceived as particularly vulnerable to a conspiracy because many of its members, prisoners of “populist illusions,” shied away from the application of strong military force to suppress the Bolsheviks and to bring a halt to expanding anarchy. Peasants, workers, soldiers, and sailors are seen as self-interested “rabble,” devoid of political consciousness and above all susceptible to manipulation by the Bolsheviks.

Advertisement

To be sure, in this view the party in 1917 was not yet the highly disciplined, wholly subservient “machine” that it was to become and that it is assumed Lenin desired. But internal party differences are seen as having been limited to periodic theoretical debates (primarily arguments between Lenin and more moderately inclined members of the Central Committee); tactical disputes between Lenin and Trotsky on the eve of the October days; and occasional excesses of revolutionary zeal on the part of rank-and-file Bolshevik extremists. The possibility that the Bolsheviks may actually have derived strength and vitality from the absence of a highly centralized, rigidly authoritarian, conspiratorial organizational structure, indeed that this may have been an important factor in their success, is implicitly excluded. Rather, the Bolshevik achievement is attributed largely to the fact that Lenin, single-mindedly tent on seizing power in order to create a one-party dictatorship, somehow managed to retain a central hard core of loyal subordinates ready to do his bidding.

Some of the differences in our respective views on the revolution alluded to above are reflected, I think, in Professor Schapiro’s criticism of my failure to discuss Provisional Government attitudes toward the Red Guard. I take it Professor Schapiro believes that the successful build-up of a powerful “private army” was a key aspect in the development of the Bolsheviks’ fighting capacity and an important precondition of a successful coup; the fact that Kerensky may have stood idly by while such a potentially threatening force was being created must appear as a sign of his government’s flabbiness. In this regard my research, like that of Professor Keep, indicates that the strength, organization, and role of the Petrograd Red Guard in the October seizure of power has been greatly exaggerated. In part because of this, the Provisional Government’s policy toward the Red Guard, or rather its failure to crack down on such paramilitary groups, was not a problem to which it was possible, or necessary, to devote a great deal of independent attention.

I suspect that interpretative differences are also behind Professor Schapiro’s objection to my use of the term “counterrevolutionary” with reference to General Lavr Kornilov, the leader of an abortive military putsch against the Provisional Government in late August. Professor Schapiro considers General Kornilov just a “simple soldier…above all anxious to restore discipline and order in a country that was galloping toward anarchy under the weak leadership of the Provisional Government.” Kornilov was not a “counterrevolutionary,” Professor Schapiro writes, because there is no evidence that he wanted to restore the monarchy.

Yet it hardly makes sense to define counterrevolution simply as a formal call for a restoration, if only because by the summer of 1917 the Tsarist regime was so badly discredited that a restoration was not a tenable objective. As commander of the Petrograd garrison during the height of the April crisis, Kornilov had called out his artillery with the intent of using it against demonstrating workers and soldiers (beginning at this time, among workers and soldiers in the capital, Kornilov’s name fast became synonymous with repression and counterrevolution). At front headquarters in Mogilev, from the middle of July when he took command of Russian forces, Kornilov was constantly surrounded by representatives of a host of ultra-reactionary officer groups. In sets of demands that the general personally delivered to government ministers during the first half of August, Kornilov insisted upon not only a return to the hated old order among troops in battle zones and the extension of repressive measures to military forces everywhere in Russia, but also the most drastic military controls over all rail lines and factories. To command the select military force that he dispatched to the capital for the purpose of imposing a military dictatorship, he hand-picked an arch reactionary, General Krymov, whose ambition forcibly to crush such popular revolutionary political institutions as the Soviets and to reverse the changes wrought by the revolution was well known. In view of this, to a considerable spectrum of political leaders at the time, and to the Russian lower classes generally, it appeared incontestable that Kornilov was bent on “counterrevolution.” They immediately banded together in active defense of the revolution. Surely this was one of the most powerful, effective displays of largely spontaneous unified mass political action in history. Kornilov was defeated in a few days, without a shot having been fired. Nearly sixty years later, the term, “counterrevolutionary,” applied to Kornilov and his movement, still seems appropriate.

Alexander Rabinowitch

Indiana University

Advertisement

Bloomington, Indiana

To the Editors:

I was surprised and disturbed by a curious sentence in Leonard Schapiro’s article on “The Real Russian Revolution.” Speaking of what seems to him to be a non sequitur in Charles Bettelheim’s reasoning (Bettelheim apparently says that only a small percentage of government functionaries favored the Soviet regime in 1917), Shapiro remarks: “I dare say. But what has lack of support of the Soviet regime got to do with the ‘bourgeoisie’? One does not have to be ‘bourgeois’ to object to the Cheka, concentration camps, atheism, and arbitrary violence.” If Schapiro thinks that the Russian Revolution was nothing more than that, he is entitled to his opinion. But he seems to be making an entirely gratuitous equation between concentration camps, etc., and atheism, and that does not seem to me to be in any way a defensible position. Does he perhaps take the viewpoint of the nineteenth-century Spanish Church, that everything from workers’ movements to children talking back to their parents was directly attributable to “followers of Voltaire” and “atheism”? I am perhaps an interested party; I am an atheist and have known many others; I have never heard any of them advocate concentration camps and arbitrary violence, nor have I ever done so myself. On the contrary, I and others have done what little we could to protest these things when they have appeared. Perhaps this equation is an oversight on Schapiro’s part, or perhaps it is a sign that his article should be taken with a grain of salt, since he seems to be approaching his subject from preconceived and (in this case) quite erroneous notions.

Martha G. Krow-Lucal

Harvard University

Cambridge, Massachusetts

To the Editors:

In Leonard Schapiro’s review-article, “Two Years that Shook the World,” he showed a concern for what he called historical “objectivity,” but I question his own. First, there is the following passage:

Dr. Keep…shows the growing revolt of the countryside in 1917, which played a part in bringing about the “revolutionary situation” that the Bolsheviks could exploit in the cities—not that the peasants were politically minded so much as intent on settling private scores or making use of the breakdown of order to grab what they could. In this context, Dr. Keep is fully aware of the responsibility of the Provisional Government in bringing about this breakdown of order, though I do not think that he sufficiently stresses the populist sentimentality of the members of this government which really destroyed any resolve to maintain order.

If peasants take action against a landlord, then there is surely more going on than private scores being settled. When landlords gain more land, I suppose the author would call it expanding business, but when peasants do it, outside the legal framework created by and for the rich, it is called “grabbing.” The order that was breaking down well deserved its dissolution. As opposed to “populist sentimentality,” Schapiro seems to be upholding the property rights instituted under feudalism and monarchy. These “unpolitical” and disorderly creatures carried out a social revolution on their own terms, to satisfy their own needs. Not to take them seriously is arrogant and elitist, qualities hardly becoming an objective historian. Short of the totalitarian order Lenin finally did impose, what kind of governmental “order” could have coexisted with the Russian social revolution? Either the revolution continued, at the peril of centralized order, or government continued, at the peril of the social revolution. To speak about maintaining order during a revolution is deceptive unless one specifies the kind of order one has in mind.

I also question the objectivity of his remarks on the Petrograd soldiers. He sounds more like Carlyle on the French Revolution than a responsible historian when he calls the soldiers an “idle, demoralized and corrupt mob.” How are the soldiers “idle”? Because they’re not fighting in a nationalistic war? Are they demoralized over the military or the revolution? “Corrupt”? “Mob”? These are terribly loose words for an historian to throw around. But Schapiro goes on to say that the soldiers (the “mob”) had “a vested interest in revolution since so many soldiers and sailors had murdered so many of their officers and would have been hanged in the event of a failure of the revolution.” Are we to lament that the soldiers did not get hanged? It seems that the author is upholding the rationality of the military system. But even more interesting is his way of characterizing the situation. To say that the soldiers had a “vested interest” in revolution because some had rebelled against the military is curious; it is like saying that many American colonists had a vested interest in defeating the British because if the Americans lost, many would get hanged for treason.

Another way in which Schapiro displays his own brand of objectivity is his not even mentioning the part played in the events by the Russian anarchists, nor the efforts by anarchists since the 1920s to discredit the Bolshevik myth. Paul Avrich, Voline, Peter Arshinov, Emma Goldman, Victor Serge, and Alexander Berkman are only some of the authors he could have cited.

The Kerensky government was unpopular with peasants, soldiers, and workers who were creating a social revolution, forming factory committees, communes, free schools, and guerrilla armies. Lenin exploited this revolution and its discontent with Kerensky; using an anarchist rhetoric in the April Theses and other speeches, he gained popular support for a program that never materialized. Regardless of Kornilov or Kerensky, the social revolution would have inevitably conflicted with any kind of government, even, I suspect, a bona fide Soviet democracy which Lenin promised and then subverted. The degree of resistance to both Kerensky and Lenin was considerable and certainly under-estimated by Schapiro. In addition to the Kronstadt rebellion, there were the activities of the Ukrainian peasant anarchists and Makhno’s guerrilla army. There was also urban resistance. Shortly after Lenin seized power, he began to suppress anarchism, the movement and its ideas. In April 1918, twenty-six anarchist centers in Moscow were raided by the Cheka, resulting in forty anarchist casualties, and 500 prisoners (Paul Avrich, The Russian Anarchists, Princeton, 1967, p. 184). One could, of course, mention other instances of resistance, such as factories that tried to maintain and extend workers’ control. Considering the context in which the revolution existed—war, famine, and then civil war—it is remarkable that it succeeded as well as it did. Schapiro implies that if the politicians in the capital had been more astute, less “sentimental,” more tough-minded, then the Leninist coup might not have happened, and presumably a bourgeois democracy would have flourished instead. The social revolution, however, did not occur for the inconvenience of politicians; it was a serious effort to transform society according to the needs of ordinary working people. It is ironic, of course, that Lenin was the one to destroy the social revolution that the Provisional Government tolerated and only tried to contain, but sooner or later, that government too would have had to assert its power or become obsolete. If Professor Schapiro had had anything to say about the matter, it would have been, no doubt, sooner.

Michael H. Scrivener

Ypsilanti, Michigan

Leonard Schapiro replies:

I hope that nothing which I have written has suggested any lack of admiration for Professor Rabinowitch’s achievement. If I have conveyed this impression I can only say that nothing was further from my intention, and I am very sorry. As regards Professor Rabinowitch’s main point, I may have unintentionally overemphasized one aspect of his book—but surely it cannot be suggested that the point I made is not central to the understanding of Lenin’s victory? Or that the material so skillfully presented and analyzed by Professor Rabinowitch does not prove it up to the hilt? Lenin’s revolutionary genius lay precisely in using the mass support for popular government depicted by Professor Rabinowitch in order to establish what he always intended to create—a party government which would harness and control the spontaneity which he detested. Indeed, it was in this that his originality appeared. I agree that it is possible to overstress the conspiratorial aspect of October—though it certainly played a part. As for Kornilov’s “counterrevolution,” this may be a semantic question. I do not think that the evidence amounts to more than that, as a soldier, he saw his mission as restoring order in the midst of the chaos created by the combined efforts of the Provisional Government and the Bolsheviks. Looking back, I do not see that this was more incompatible with the aims of “the Revolution” than what happened after October. Be that as it may, I hope that nothing in my review in any way diminishes the fact that I consider Professor Rabinowitch’s account of the Kornilov affair to be by far the best that I have read.

Martha G. Krow-Lucal seems to have misunderstood what I wrote. I merely pointed out the obvious fact that it was not necessary for Russians who, in their millions, disliked bolshevism for its policies—which included militant atheism—to be classified as “bourgeois” (whatever that may mean). If Michael H. Scrivener likes to describe the chaos and disorder of the period of the Provisional Government as a popular revolution that is his business. It is a view I do not share. But he is surely wrong in his facts if he believes, as he seems to—no doubt under the influence of sixty years of Soviet propaganda—that the Bolsheviks overthrew an oppressive regime, and not what Lenin admitted was the most libertarian regime in the world. I have done, I hope, justice to many brave anarchists in my books. Their contribution was not relevant to the subject dealt with by the works I was reviewing.

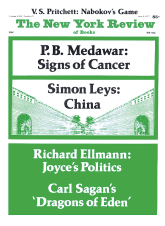

This Issue

June 9, 1977