Norman Mailer went out running with Muhammad Ali one morning, a few days before the fight with George Foreman in Zaire. He asked me to go with him, but I thought of the long ride to Ali’s training camp at N’Sele in the darkness, and thumping along for five miles or so in the wake of the challenger, and, besides, I had done that sort of thing before with Joe Frazier. So I begged off. I said I didn’t have any equipment to run in.

We came in very late from the gambling casinos in Kinshasa—around three in the morning—and Mailer was just coming through the lobby on his way out to his car. He had sneakers on, and long athletic socks rolled up over the legs of what was probably a track suit but of a woolly texture that made it look more like a union suit, so that as he came through the lobby Norman gave the appearance of a hotel guest forced to evacuate his room in his underwear because of fire: the impression was heightened by the fact that he was carrying a toilet kit.

That night he and I had dinner and he told me what had happened. He had kept up with Ali for a couple of miles into the country upriver from the compound at N’Sele, but then he had begun to tire, and finally he stopped, his chest heaving, and he watched Ali disappear into the night with his sparring partners. In the east, over the hills, the African night was beginning to give way to the first streaks of dawn, but it was still very dark. Suddenly, and seemingly so close that it made him start, came the reverberating roar of a lion, an unmistakable coughing, grunting sound that seemed to come from all sides—just as one had read it did in Hemingway or Ruark—and Norman turned and set out for the distant lights of N’Sele at a hasty clip. He told me he had been instantly provided with a substantial “second wind” and he found himself moving along much quicker than during his outbound trip. He reached N’Sele safely, jogging by the dark compounds, exhilarated not only by his escape but by the irresistible thought of how highly dramatic it would have been if he hadn’t made it.

I asked him what he was talking about, and he grinned shyly and began to admit that once he had got to the sanctuary of the compound he had been quite taken by the fancy of being finished off right there by the lion…all in all not a bad way to go, certainly a dramatic death right up there with the more memorable of the litterateurs’—Saint-Exupéry’s or Shelley’s or Rupert Brooke’s—and the thought crossed his mind what an enviable last line for the biographical notes in the big dun-colored high-school anthologies: that Norman Mailer had been killed by an African lion near the banks of the Zaire in his fifty-first year.

Well, his fancy had all come to dross, he went on, because Muhammad Ali had returned from his run, his villa crowded with his people, and Norman had not been able to resist revealing the incident of the lion. It was greeted first with silence, everybody looking at him, and then the laughter started, first giggles, then hard thigh-slapping whoops, because they had all heard the lion, too, and heard him just about every morning, because that lion was behind bars in the presidential compound, a zoo lion—there weren’t any lions in the wild in West Africa anyway—and the thought of Mailer’s eyes staring into the darkness, and his legs pumping in his union-suit track clothes to get himself out of there (“Feets, do your stuff”) was so rich that Ali’s friend Bundini finally asked him to tell them about it all over again. “Nawmin, tell us ’bout the big lion!”

It was interesting listening to Mailer talk about this—quite shyly and not without self-mockery, and yet with a curious wistfulness. He told me that the other fancy of this sort which he could remember involved a whale he had seen swimming through a regatta off Provincetown, Massachusetts—very impressive sight—and he thought that would not be a bad obituary note either: “Taken by a whale off Cape Cod in his fifty-first year.” Hemingway? Melville? He couldn’t make up his mind.

Later that evening, in the bar at the Inter-Continental, I found myself talking to an Englishwoman who described herself as a “free-lance poet.” She was hitchhiking her way up the west coast of Africa. I thought of her standing in a dusty African road in the darkness of the early dawn, and I mentioned Mailer’s fantasy. “Consumed by a lion? What on earth for?” she asked. Her eyes widened, as if she had suddenly seen an image, and she said that she thought—if one had to “shuffle off”—it would be terrific to be electrocuted while playing a bass guitar in a rock group.

Advertisement

“Oh, yes,” I said.

“I think it happens quite often,” she told me. She had an idea that rock groups which flickered into vague prominence, with a hit record perhaps, and were not heard of again were actually victims of electrocution. “In Alabama in the summer, that’s when it happens,” she said. “In an open-air concert in a meadow outside of town where they’ve built a big stage of pine, and the quick summer storms come through, or the local electricians aren’t the best, and all of a sudden zip!—the top guitarist of the Four Nuts, or the Wild Hens, or whatever, glows briefly up there on the stage, his hair standing up like an old-fashioned shaving brush, and he’s gone.”

“Zip?”

“Zip,” she said. “I’m practically tone deaf and I can’t play a thing, but that’s how I’d like to shuffle off…all those faces out there in the darkness, and the rhythm just pounding all around….”

She suddenly asked me how I saw myself “shuffling off.” I had an awkward time telling her, my standard fantasy coming from an innocent time when I thought of death as a very attractive pose people got into when they had performed a great heroic deed—brave soldiers lying in graceful attitudes in the poppy fields, their rifles beside them—and since at that time the most important deeds I thought to be associated with sports, I usually saw myself “shuffling off”—as she put it—in Yankee Stadium…sometimes as a batter beaned by a villainous man with a beard, occasionally as an outfielder running into the monuments that once stood in deep center field…a slight crumpled figure against the grass. The fantasy had not changed that much—still that thirteen-year-old whiz center fielder, bong! lying out there and the crowd rising. Quite unoriginal.

“You’re right,” the poet said. “Boring. I’ve changed my mind, incidentally, about mine,” she went on. “What on earth could I have been thinking of?” She announced that she wanted to be raped to death by an ape.

I did not see her around the hotel after that. She had no interest in the fight at all, and though it was just a day or so away, she would not have stayed for it. I made some notes about her death fantasies. And about Mailer’s, of course. It occurred to me that writers traditionally do seem to come to dramatic ends themselves, as if they deserved the same ironic or bizarre conclusions they so often gave the characters in their books.

The Russian writers: Tolstoy, packing his knapsack and setting off from home on that last strange journey of his that ended up at the railroad station at Astapovo, where he died in the stationmaster’s room; or Gogol, with leeches on his great nose, the bishops filing slowly by, as he lay thinking how he could destroy all extant copies of Dead Souls; or Chekhov, packed in a box labeled OYSTERS, being transported back home on a bed of ice from the Black Forest where he died.

It was not only the manner in which certain writers died that was interesting: often they managed to push out a memorable last word or two which seemed too studied even to put into fiction: Goethe’s “More light!” or Henry James’s “Ah, it is here, that distinguished thing”—now discounted by Leon Edel. Some of the words which one would like to have overheard were lost, of course. Aeschylus must have had a final comment on being conked by the turtle which an eagle, trying to break it on the rocks below for a meal, dropped on the dramatist’s bald pate. In my notes I imagined Aeschylus regaining consciousness briefly:

“What happened?”

“Well, sire, you were hit on top of the head.”

“By what? It felt awful.”

“A turtle.”

Then the memorable phrase must have come, just a faint, unheard murmur, before the dramatist’s eyes clouded over.

When I got back to the US I told some friends about Mailer’s lion. Kurt Vonnegut said he thought Mailer must have been crazy to pick anything like that—the rip of claws, that huge cat breath. Then John Updike wrote me a letter in which he urged me to look up what Livingstone had written in his African memoirs about being attacked by a lion; he remembered that the experience had been quoted by Darwin “to mitigate his frightful thesis of universal and continual carnage, in which the explorer describes the curious numbness that overcame him when he found himself in the mouth of a lion (who let him drop, I forget why).”

Advertisement

I looked it up: The lion that caught Livingstone—as one might have expected—was one he had wounded. While he was ramming a pair of bullets down the barrels of his flintlock weapon the lion sprang out at him from behind a small bush and caught him by the shoulder. “Growling horribly close to my ear,” Livingstone wrote, “he shook me as a terrier dog does a rat. The shock produced a stupor similar to that which seems to be felt by a mouse after the first shake of the cat. It caused a sort of dreaminess, in which there was no sense of pain nor feeling of terror, though I was quite conscious of all that was happening. It was like what patients partially under the influence of chloroform describe, who see all the operation, but feel not the knife. This singular condition was not the result of any mental process. The shake annihilated fear, and allowed no sense of horror in looking around at the beast. This peculiar state is probably produced in all animals killed by the carnivores, and, if so, is a merciful provision by our benevolent Creator for lessening the pain of death. Turning around to relieve myself of the weight, as he had one paw on the back of my head, I saw his eyes directed at Mebalwe, who was trying to shoot him at a distance of ten or fifteen yards. His gun, a flint one, missed fire in both barrels; the lion immediately left me and, attacking Mebalwe, bit his thigh. Another man, whose life I had saved before, after he had been tossed by a buffalo, attempted to spear the lion while he was biting Mebalwe. He left Mebalwe and caught this man by the shoulder, but at that moment the bullets he had received took effect, and he fell down dead. The whole was the work of a few moments.”

The details—the peacefulness described—were reassuring. It was not such an awful finale for Mailer to have pictured after all. I sent him a copy of the Livingstone material along with a note. Certainly such an end weighed favorably against his other fancy—death by whale—which would have been dark, the sound of water sloshing about…abysmally foreign.

The subject stuck to my mind. I asked friends at dinner—“I’m collecting deaths,” I’d say, as if I were pinning moths to a collecting-board. In libraries I looked into the back stretches of biographies. My notes grew. Robert Alan Arthur said one night that the subject of death so often recalled for him a vignette at the assassination of Sitting Bull—that the old chief had a stallion named Grey Ghost he rode in Bill Cody’s Wild West Show who had been trained to rear up prettily at the sound of a gunshot and dance on his hind hooves…and that when Sitting Bull was gunned down by Indian police there was a great stirring in the yard, and they looked over to see the horse responding to his cue, his great height, and the front legs pawing at the air.

I told someone about Sitting Bull’s horse, and he said, “Oh yes,” in a very arch way, and mentioned Gérard de Nerval’s raven. “Nerval hanged himself on a winter night with an apron string he thought was the Queen of Sheba’s garter,” my informant said. “He had taken to carrying it around with him in his meanderings through Paris; he tied it through the bars of a grating in a stone staircase near the Place du Chatêlet. The police discovered him hanging from it, with a raven capering around him repeating the only words it had been taught by its owner, ‘J’ai soif. J’ai soif.'”

John Cheever told me about the death of E.E. Cummings. It was September, a very hot day, and Cummings was out cutting kindling in the backyard where he lived in New Hampshire. His wife, Marion, looked out the window and asked, “Cummings, isn’t it frightfully hot to be chopping wood?” He said, “I’m going to stop now, but I’m going to sharpen the axe before I put it up, dear.” I wrote the scene down on the back of an envelope. Cheever looked at me oddly, and I told him I was making a collection. “I see,” he said. “Well, those were his last words.” I told him how grateful I was.

I went after others. I worried vaguely about myself…this steady preoccupation, but it did not seem to deter me. I called a friend at Harper’s magazine whose name is Timothy Dickinson. He would have much to offer. One of his functions at the magazine is to be asked questions; he is a tremendous source of knowledge, a sort of living house encyclopedia. One can drop in at his office and ask him what he knows about Holstein’s great work on the army ant, and it will be an hour before one is able to escape. I had first been astonished by him when he began telling me more about my forebears—in particular, a Civil War general named Adelbert Ames—than I knew myself. He speaks in quick explosions of verbiage, often shifting from one language to another, lacing himself on with “Think, Dickinson, think!” as he takes one back with him into fine labyrinthine areas of arcane knowledge.

He looks like an overgrown schoolboy from the English public-school system—which indeed produced him—with his black morning coat and trousers (I have never seen him in anything else), a white boutonniere to brighten the ensemble, along with a watch-chain running across his vestcoat. He carries a silver-knobbed cane with him everywhere, even indoors, and when he stands and talks, he keeps it tucked away under one arm like a swagger stick. People behind him at cocktail parties get poked. He was great company, though I always came away from him keenly aware of the empty stretches in my brain, knowing that if his was a cluttered bibliothèque-like vaulted chamber with balconies, great banks of volumes rising up, mine suffered badly in comparison—a broom closet off a corridor, a can of paint up on a shelf.

But it was always worth the intimidation. When I reached Timothy to ask him if he could supply me with some interesting artistic persons’ deaths or last words—such as Goethe’s “More light!”—I heard him clear his throat delicately on the other end of the phone. “Well, Goethe might have said, ‘More light!’ very likely indeed. But it was probably a penultimate request: his very last words were almost surely ‘Little wife, give me your little paw.'”

“Oh, yes.”

“Weibchen, gib’ mir doch deine kleine Tatze.”

“Yes, of course.”

“He kept hopping out of bed in his nightgown to assure himself that he was still alive. Quite undignified. Teddy Roosevelt said, ‘Put out the light!’ but I don’t suppose he’s literary enough for you. It’s true, isn’t it, that the literary find distinctive ends. Pushkin was killed in a duel. Ambrose Bierce simply vanished, didn’t he? And so did Villon. So many of them drowned, of course…they seemed to have a thirst for it…Shelley, Virginia Woolf, Hart Crane.”

Dickinson was hurrying on. “Naturally, we have Brune, the rather obscure French dramatist who became better known as a marshal in the military…lynched he was, and at the end he had the presence to complain, ‘To live through a hundred battles, and to die hanging from a lantern in Provence.’ Let’s see. Think, Dickinson, think! Well, Gibbon, of course, said, ‘All is dark and doubtful.’ And then we have those mysterious words of Thoreau: ‘Moose!…Indian!’ Samuel Butler asked, ‘Have you the checkbook, Alfred?'”

I thought to interrupt and ask who Alfred was, but I stopped myself, realizing that Timothy would probably know, and we would get sidetracked for a time.

“Chesterfield, of course…great gentleman to the end. A friend was invited into the bed chamber, and Chesterfield murmured with his final breath, ‘Give Dayrell a chair….'”

I couldn’t resist testing him. Who might Dayrell be?

“The Swiss scholar…one of the great Geneva family of Dayrells.” I could hear Timothy snap his fingers. “I have some more. Aubrey Beardsley hoped to leave with a clean house: ‘I am imploring you,’ he said, ‘burn all the indecent poems and drawings.’ Lytton Strachey said, ‘If this is dying, I don’t think much of it.’ There were other complainers. Oliver Goldsmith was asked, ‘Is your mind at ease?’ ‘No, it is not,’ he said quite briskly, and died. Jonathan Swift complained, ‘I am dying like a poisoned rat in a hole.’ Then, of course, there were those much more comfortable with the situation. Hazlitt exclaimed, ‘Well, it’s been a happy life’—such an astonishing sentiment considering what a miserable time he did have of it—domestic problems, temper tantrums, and the rest…. Let’s see. Ellen Terry—not quite the right category, but she’s irresistible: she leaned out of her bed and wrote in the dust on her bedside table the word ‘happy.'”

Timothy paused. “A lot of them were hard at work at the time,” he went on. “Setting a good example. Petrarch, a day before his seventieth birthday, was discovered with his head pillowed on a manuscript of Virgil’s. Bede was dictating his translation of the Bible to the end. Rossetti wrote an excellent poem on his deathbed: it’s the one that starts:

Our mother rose from where she sat:

Her needles, as she laid them down,

Met lightly, and her silken gown

Settled—no other noise than that.

Glory unto the newly born!…

“What about women authors?” I interrupted desperately.

“Well, let’s see. Think, Dickinson, think. Not especially sensational, but when friends came in to tell Mrs. Trollope, who was very ill indeed, that Anthony had arrived from America and was hurrying to be at her bedside, she asked, ‘Who is Anthony, and pray tell where is America?’—an odd question since she lived for some years in Cincinnati and, of course, wrote The Domestic Manners of the Americans.”

Timothy paused at the other end of the phone.

“Do you know General Sedgwick’s?”

“General—?”

“Oh, hardly a literary man, but you should know him anyway. He was in the Sixth Corps with your great-grandfather, Adelbert Ames. He died in the Wilderness. Oh, his is excellent! He said, ‘Oh, they couldn’t hit an elephant at this dist—'”

“What?”

“Yes. Absolutely what happened. General Sedgwick put his head up over a parapet to look at the enemy lines. Somebody must have warned him, and that’s what he said, in considerable scorn: ‘Oh, they couldn’t hit an elephant at this dist—’ Last words. Very nice.”

With all this in mind, I could not resist writing a few contemporary artistic acquaintances and asking them if they would turn their minds to how they might see their own ends. William Styron, James Jones, Capote, Terry Southern, Gore Vidal, Jules Feiffer, Hunter Thompson. I could never bring myself to ask them in person…seeing them at some social function…perhaps because a topic never came up which invited me to lean in easily and inquire, “Oh…wondered…death…if you might describe….”

So I wrote them a careful letter, rank with apology, remarking that I felt I was conducting the sort of assignment junior editors at Harper’s Bazaar, fresh from Vassar, are required to undertake. I told them about Mailer and the lion. I gave them the example of Jean Borotra, the great French tennis star, who liked to think of himself succumbing just as he served an ace on center court at Wimbledon. The letter was typed. It asked for a scene, or a deathbed quip. The copies sat around on my desk. Then after a while I sent them out.

The replies were varied. Gore Vidal’s was predictably apocalyptic, though he neglected to give the circumstances. “When I go, everyone goes with me,” he wrote. “You are all figments of my waking dreams and I suggest that each and every one of you shapes up and prays that I live long.” Woody Allen’s was terrifyingly private in comparison, an echo of his film Love and Death, in which Death takes on a corporeal form: “I enter a house where I have been invited. It’s dark. Two large, silhouetted figures emerge from hiding. Their voices are familiar, though I can’t place them accurately. One says, ‘It’s him.’ The other says, ‘I hope so.’ Suddenly one grabs me and pins my arms to my side while the other holds a small pillow across my face. At first, the pillow is not centered properly and it takes some effort for me to adjust it…. Just before I succumb I hear one of the figures say, ‘we did this because it was important, though not absolutely necessary.'”

Jules Feiffer sent the accompanying cartoon.

Allen Ginsberg, who wrote that he was spending an increasing amount of time in the “company of Buddhists,” allowed that for him there was very little difference between death and the deeper levels of meditation; he made it sound like a form of relaxation. “Dying,” he told me, “I do that every time I sit down on my Zafree [which turned out to be a meditation pillow, thank Heavens], abandon my mind, observe thought-form fading, and the gaps between thought-forms, and breathe out my preoccupations. At the moment, one ideal death would be sitting on a pillow with empty mind.”

John Updike also rather liked the idea of suspension. “Thoughts on dying? I can’t decide if I’d rather go after the thirteenth or the fourteenth line of a sonnet; the thirteenth would give you something to do in the afterlife. By the same reasoning, while the ball is in the air, off the face of a perfectly swung five-iron, and yet has not hit the green where it is certain to fall.”

James Dickey wrote me he dreams of voyages—his house is full of sextants and other navigational aids—and that he wished to die of navigational ineptitude, finding himself in Fiji in the hurricane season. “I wish the wind to begin to blow and the waves to roar. I will leave the sails up, so that I can hear the mast go like a barrage from the long guns of the Storm King’s fleet…sit in the dark cabin listening to the nails squeak as the hull is pulled apart. I shall then go on deck and founder with the ship, backing slowly off from it under water, as the craft sails down. The sky shall be clear, now, and I would like to catch one last glance of the moon through the thickening film and then feel it dance invisibly over me as I inhale the whole ocean.”

An appropriate death for a poet who would, as he has said, like to be reincarnated as a migratory seabird—a tern, perhaps, or an albatross. Joseph Heller, on the other hand, wrote that he had never given any thought to the matter, and on receipt of my letter had not really given any serious consideration either. “I expect,” he wrote, “I really don’t care much how it will happen, and I don’t think I will care much more when it does. ‘What a pity!’ is about all I’ll think, if I’m able to think at all, and ‘What a pity!’ pretty much sums up the way I think about it now.”

How awful, I thought, when I received the Heller reply—I’ve given him a rotten day. For him it was not a question of fancy at all. “I know you want the truth,” he had concluded his letter.

Terry Southern’s contribution of a “sports death-fantasy” was sexual, not surprising from the author of Candy. But even Southern found its complexity a bit “odd.” His lengthy fantasy seemed to stem from “early visits with Gore Vidal and Larry Rivers to China—not your mainland China, mind, but your tiny off-land China”—to cover (for a quality slick magazine named Pubes) the “highly touted Great Ice Ping-Pong Tournament.” Southern continued:

“As sports buffs will recall, the sport did not differ from ordinary ping-pong so much en principe as in the actual mechanics of the game—making use as they did of rounded ice cubes instead of the conventional hollow plastic balls, and using foam-rubber padding on both table and paddle surfaces to afford the necessary resilience for the bouncing cubes.

“I was attending the ‘Young Ladies Finals’ when the incident in question occurred. The contestants, ages fifteen to twenty-one, were clad ostensibly to give them ‘the maximum in freedom of movement,’ in what can only be termed the ‘scantiest attire.’ In fact there was a thinly veiled aura of pure sexuality surrounding the entire proceedings, so it did not come as a total surprise when I was approached by one of the ‘Officials,’ a Mr. ‘Wong Dong,’ if one may believe him, who, with a broad grin and a great deal of ceremonious bowing and scraping, asked if I would care to meet one of the competitors. ‘Very interesting,’ he insisted, ‘a top contender.’

“I agreed, and soon found myself in an open alcove with ‘Kim.’ A most attractive girl of eighteen or so—attractive except for what I first thought of as ‘rather puffy cheeks.’ I soon learned however that the puffiness was caused merely by the presence and pressure of an ice cube in each cheek—this being the technique of preparing the ice balls (‘la préparation des boules‘) for play, holding the cubes in the cheeks until they melted slightly to a roundness.

“The girl seemed extremely friendly, and Mr. D. now asked to examine the cubes. ‘Ah,’ he said, beaming, when she produced them—two glittering golf-ball size pieces of ice—one in each upturned hand. ‘We have arrived at a propitious moment,’ he continued, turning to me again, ‘the boules are now of ideal proportion for…la grande extase des boules de glace.’

“Not entirely devoid of a certain worldliness, I had heard of the infamous ‘ice cube job,’ as it was commonly known—the damnable practice in my view of fellatio interruptus, or according to other sources, ‘fellatio prolongata‘—whereby at the moment of climax, the party rendering fellatio, with an ice cube in each cheek, presses them vigorously against the member, producing a dramatic countereffect to the ejaculation in progress. As I say, I was aware of the so-called ‘extase des boules de glace,’ but had never experienced it—nor, and I would be less than candid if I did not say so, was I particularly keen—though, of course, I did not wish to offend my host—who then spoke to the girl in Chinese, before turning to me.

“‘It is arranged,’ he exclaimed happily. ‘Allow her to grasp and caress your genitalia.’ And returning the cubes to her mouth, she extended her hand in a manner at once both coy and compelling, and with a grace charming to behold. Even so, I was not prepared to respond to this gesture without first working up a bit of heft.

“I adroitly stepped just beyond her reach, though quite without ostentation so as not to offend. ‘Perhaps we should, uh, wait,’ I said, glancing about the room as though wanting more privacy.

“‘Ah,’ observed Mr. D. with a most preceptive smile, ‘you shall be quite comfortable here. I assure you.’ And so saying, he drew closed a beaded curtain, and then stepped through it, bowing graciously as he departed.

“Alone with Miss Kim, I felt immediately more secure, and a slight unobtrusive squeeze assured me that a fairly respectable tumess was near at hand.

“‘Very well, Miss Kim,’ I told her, ‘you may, uh, proceed,…’ which she did, with, I can assure you, the utmost art and ardor. We had been thus engaged for several moments, and I was just approaching a tremendous crescendo—indeed was actually into it, when the beaded veil was burst asunder and in rushed two madcaps, Vidal and Rivers!

“‘Get cracking, you oafish rake!’ shrieked Vidal with a cackle of glee and inserted two large amyl nitrate ampules, one in each of my nostrils, and then popped them in double quick order. Simultaneous to this, Miss Kim pressed with great vigor the two ice cubes against my pulsating member, and the diabolic Rivers injected a heady potion of amphetamine laced with Spanish Fly into my templer vein. The confluence and outrageous conflict of these various stimuli threw my senses into such monstrous turmoil that I was sent reeling backward as from the impact of an electric shock, torn from the avid embrace of the fabulous Miss Kim, who bounded after me in hotly voracious pursuit, screaming: ‘Wait! L’extase des boules de glace COMMENCE!’ I now lay supine as she swooped down to resume her carnivorous devastation, while around us, obviously themselves in the crazed throes of sense-derangement, Vidal and Rivers pranced and cavorted as though obsessed by some mad dervish or tarantella of the Damned! Thus my monumental and unleashed orgasm, prolonged (throughout eternity it seemed!) by the pressure of the boules, and intensified beyond endurance by drogues variées, caused me to expire, in a shuddering spasm of delirium and delight. Ecstasy beyond all bearing! Death beyond all caring! ‘I die!’ I shouted (as I still do when I relive the experience)…’FULFILLED!!!'”

Southern went on to say in a postscript that of course he did not actually succumb (“Oh no, Vidal and Rivers had other plans”) and that just in time, “A newly arrived member of our party, the near-legendary ‘Dr. Benway’ (who later gained certain prominence as an author using the name William S. Burroughs) administered certain so-called ‘remedial elixirs’ (the exact nature of which I have never ascertained) and brought me around. In any event,” Southern concluded, “I continue to relive (almost nightly, in fact) the sensations of that most memorable experience.”

I have on occasion tried to explain Southern’s death fantasy to friends…but have bogged down almost immediately, quite sorry I ever got started.

“What sort of game?…”

“Well. Ice Ping-Pong it’s called…and they get the ice balls just to the right shape and consistency by revolving them in the cheeks.”

“Oh yes.”

“Machines won’t do the job right,” I said.

“No, of course not. [Pause] Well, go on. What happens then?”

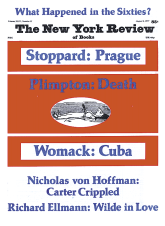

This Issue

August 4, 1977