Haifa at the opening of the Yom Kippur war. A prospering, blond-bearded, lonely garage owner discovers that his coldly hysterical schoolteacher wife has a lover, and that the lover has disappeared into the first confusion of the war. The army has no record of him. The husband sets out to find the lover and restore him to the wife.

The lover is the shuffling, easily confused descendant of an old Sephardic Jerusalem family, is not happy in Israel, and has returned from Paris only to claim an inheritance; his grandmother is supposed to be dying. The uneducated husband does not feel snubbed by a relationship between wife and lover founded on a cultural piety for French; in his tow truck he roams Israel looking for the lover’s 1947 blue Morris because he wants to re-establish some connections in his sleepless family and frightened land. The “War of Atonement,” as some Israelis now bitterly call it, revealed as part of the national vulnerability so much friction and anxiety that the husband, already troubled by his adolescent daughter’s fear for the family, seems more interested in getting the lover to calm the wife down than he is in claiming the wife for himself.

Missing connections, family anomie, and breakup inadmissable to Jewish piety and Israeli solidarity (but of course not exclusive of endless family discussions) are the favorite themes of the delicate and ironic young Israeli novelist Avraham Yehoshua. In two books of stories, Three Days and a Child and Early in the Summer of 1970, Yehoshua brought to his stories of alienation and antagonism within the Israeli family such fine political shading that I am not surprised to find in the comic situation of The Lover, his first novel, a parallel comedy of Arab-Jewish distrust that does not shirk the ferocity that grows every month. Through the eyes both of a fifteen-year-old Arab working in the husband’s garage and of the lover’s ninety-year-old grandmother (the busy husband gets so pent-up looking for the lover that he has the boy also looking after the old lady) we see an Arab and an Israeli locked into a debate of proximity, alikeness, mental hatred, a debate that Yehoshua’s superb ability to render both presences relieves of all sentimentality.

Tightening brakes all the time. Lying underneath the cars and shouting to the Jews, “Press, let go, harder, ease off, slowly, press.” The Jews do exactly what I tell them….

They’re talking about war again and the radio’s buzzing all the time. We start listening to what the Jews are saying about themselves, all that wailing and cursing themselves, it pleases us no end. It’s nice to hear how screwed up and stupid they are and how hard things are for them, though you wouldn’t exactly think so seeing them changing their cars all the time and buying newer and bigger ones.

He’s always in a good mood, this Arab, quite content, whistling a tune, pleased with himself. God, what’s he so happy about? Walking around the house a little, eating a slice of bread, intending to go to bed just as he is. But I soon cured him of that.

“Shame on you, boy, we aren’t in Mecca, wash first.”

He was offended, going pale with anger. I had profaned the Muslim holy of holies.

“What has Mecca to do with it? Mecca is cleaner than all Israel.”

“Have you been there?”

“No, but neither have you.”

What I value most in The Lover, and never get from discourse about Israel, is a gift for equidistance—between characters, even between the feelings on both sides—that reveals the strain of keeping in balance so many necessary contradictions. The story, mounting through the repetitive, circling, lightly touching personal monologues, ends up, like a circus performer balancing his body on one finger, on a harshly concentrated equipoise that cannot hold. There is no easy sleep in this land; insomnia and night prowling pervade the novel as among Israel’s chief activities—along with endless meetings and military consciousness.

The Arab adolescent and the Jewish adolescent fall in love, make love, but cannot love for long. The lover of the garage owner’s wife, having parked his 1947 blue Morris, turns up in the army with a bazooka and a set of bombs forced on him by an Israeli officer maddened by the man’s obvious lack of commitment; the officer drives the lover into the thick of battle and leaves him. The lover deserts by joining up with some ultra-orthodox “black coats” who are roaming the battlefield—to make “converts”? The husband finally restores the lover to his own wife as if to make the house normally “full” again. But it isn’t; the daughter is off making love with the Arab boy.

Advertisement

Though the traditional “center” of Jewish existence, the family, does not hold, Yehoshua seems to suggest that the characters in their wandering and prowling and love-snatching find a perception in their isolated monologues, some imaginery volume of being, that makes a novel possible. All these lonelies, with their educational meetings, their many cars, make up a society. The characters in their isolation may not always seem real to themselves, but the country does. Hence the sense of danger that hovers over the book like the hamsin, the hot wind from the east. Although I detect some softness and old-style Zionist yearnings in the lovemaking between Arab and Jew, there is by the end of the book a steely stoicism and even an open fear on Yehoshua’s part about the destructiveness that lies ahead. Politically a leading dove, Yehoshua as a novelist is most admirable in the courage he brings to his vision of what Israel is and of necessity will continue to be.

The “lover,” whose predicament is literally to find himself in Israel when he doesn’t want to be, deserts the orthodox “black coats,” as he does the Israeli army, by describing himself as “a free man. He doesn’t owe anybody anything.”

The old man smiles.

“What is a free man?”

To hell with it, I say nothing….

The old man still stands there watching me.

“Tell me, sir, what do you mean, a free man?”

I say nothing. Tired and worn out. Almost on the brink of tears. A man of forty-six. What’s happening to me?

“Do you, sir, consider yourself a free man?”

Theological arguments now….

“So the gentleman wishes to take the automobile, let him take it, only let him not say that there is one free man in the world.”

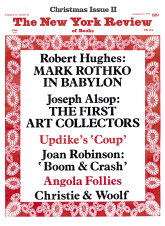

This Issue

December 21, 1978