Naples is a bewildering, irritating, bewitching, and deceptive city not only for foreigners (a term which, in Naples, includes all other Italians), but for most Neapolitans too. General Carlo Filangieri (1784-1867), prince of Satriano, duke of Taormina, could be used as an exemplary illustration of how the people themselves feel about their own city. He was the son of Gaetano, an illustrious philosopher of the Neapolitan (and European) Enlightenment, whose Scienza della legislazione, considered one of the fundamental books of the century, was famous in France and read in the United States. Benjamin Franklin was one of his admirers.

By order of Napoleon and at the expense of the République, Carlo was educated at the Prytanée, the French military school. He became an officer in the French Army, fought at Ulm, Marienzell, and Austerlitz; was later transferred to Spain, fought at Burgos and distinguished himself in the peninsular campaigns. In 1808 he was sent back to Naples and to the Neapolitan Army in disgrace because he had killed a French general in a duel. The French general had dared call Neapolitans “bougres” in his presence. The word, while etymologically equivalent to the English “bugger,” is much milder in French. In old-fashioned novels it is usually translated as “blackguard,” “scoundrel,” or “wretch.” Many years later, the old general Filangieri left his son these disenchanted words, the conclusion of a lifetime: “Credimi, per chiunque ha un po’ di onore e un po’ di sangue nelle vene è una grande calamità nascere napoletano.” (“Believe me, for anyone who has a little honor and a little blood in his veins, it is a great calamity to be born Neapolitan.”) Evidently a Neapolitan could not allow a foreigner to besmirch the honor of his countrymen, but could secretly admit that to be one was a serious handicap for an honest and courageous man.

Many foreigners on short visits often think, in their naïveté, that the city is the nearest thing to an earthly paradise. (Some, to be sure, hate it at first sight, cannot endure the spectacle of its decay and corruption, the filthy overcrowded alleys, the poverty and squalor of its people.) Those who fall in love with it are enraptured by virtually everything: the landscape, the gulf, Vesuvio, the songs, the food, and the charm of its ingenious, courageous, and unfortunate inhabitants. Like people in love, these visitors eagerly believe everything they are told and think everything and everybody around them are exactly what they seem or pretend to be. They see the Neapolitans as happy and childlike, in love with music and gay colors, satisfied with but a few drops of olive oil and a ripe tomato on a slice of bread, enjoying an occasional festa in honor of some obscure but miraculous saint, the melting of St. Januarius’ blood at regular intervals in the Cathedral, and displays of fireworks.

Foreigners who linger longer and look under the surface of things are wiser. They describe, with tears in their eyes, the misery, the cruelties, the injustice, the suffering of the people and the humiliating subterfuges necessary for them to survive. Northerners (from northern Italy and North European countries) are often overtaken by the urge to solve the Neapolitan problem once and for all. Some of them imperiously suggest simple remedies necessary to cure all the city’s ills, the remedies fashionable at the moment of writing, which had been applied elsewhere with excellent results. Why, they seem to ask, are Neapolitans whining? What are they waiting for?

Many of these visitors, the optimists as well as the pessimists, eventually publish diaries, impressions, sketches, collections of letters home, or travel books. Something about the city seems to drive people to their writing desks. The bibliography is immense. Most of these works, even those by celebrated and experienced writers like Alexandre Dumas père, F. Marion Crawford, or Charles Dickens, are readable but not very good. Only a handful stand out, written in the last century mostly by foreigners or Italians with foreign blood: Matilde Serao’s Napoli, Jessie White Mario’s La Miseria di Napoli (Matilde was half Greek, born in Patras; Jessie was English), Axel Munthe’s The Story of San Michele, Norman Douglas’s Siren Land, his Capri novel South Wind, some Frenchmen’s impressions, a few by Germans, Scandinavians, and Russians. Until a short time ago, the most moving and memorable description, in my opinion, was written by a young American, John Horne Burns. It was called The Gallery. It evoked the tragedy of the city in ruin, its people famished, bands of homeless children living in the rubble, epidemics spreading almost unchecked, near the end of the last war, when Naples was under the indifferent, bewildered, or contemptuous government of Allied officers. It evoked the shabby Galleria Umberto Primo (hence the title), where black market operators, pimps, whores, swindlers, thieves, vagabond children, and poor, starving, honest people gathered.

Advertisement

Two recent books now challenge Burns’s little masterpiece. They too do not describe Naples in good times, which are miserable at best, but in wartime, its houses destroyed by bombings, its people in rags, hungry, yet resourceful, stoical, cheerful, and heroic. Four Days of Naples, by Aubrey Menen, reconstructs the little-known bloody revolt of the people, mostly street urchins known locally as scugnizzi, who for four days fought the German soldiers in the streets and alleys, killed many of them, and drove the rest out of town before the Allies, coming from Salerno, managed to arrive and liberate Naples. The scugnizzi fought with what weapons they could lay their hands on (decrepit rifles and hand grenades abandoned by the disbanded Italian Army, or machine guns and other weapons taken from the Germans, mostly dead Germans). Many of these boys were themselves killed.

Menen knows the city intimately (he lived not far from it, in Positano, at one time, and for all I know may still live there), speaks fluent Italian and some Neapolitan dialect, has many friends in the city of all ages and from all classes. He surely knows what he is talking about. Menen has reconstructed the events he describes from German and Italian documents and from the memories of many witnesses and protagonists.

Curiously enough, several survivors were reluctant to go back to those half-forgotten days, and reluctant too to allow their names to be used. They had since become respectable and affluent middle-class family men. They did not want to be reminded of the time when they were half-naked and barefoot scugnizzi living on what they could steal, even if they had also been heroes risking their lives and killing Germans.

Menen is half Indian and half Irish. This is important. Naples has long been defined as the only large Oriental city without a European quarter. The Italians believe this to be an English saying; the English prefer to attribute it to Edoardo Scarfoglio, Naples’s most famous nineteenth-century journalist. That there was something Oriental about the city had been known to the East India Company, which found it useful to keep its young, recently recruited English employees in Naples for a stay of months before shipping them to Asia, as if Naples were a halfway point where a gentleman could begin to accustom himself to non-British surroundings.

The Indian half of Menen evidently finds it easier to understand the people and their life than a thoroughbred Englishman would. Then, too, he is Catholic. This also helped him. One cannot fully know what Naples is all about if one is not familiar, really familiar from birth, with some of the humbler aspects of the Roman Church, those which upset Protestants the most, like the importance of amulets, relics, specialized saints, the many different Madonnas, thaumaturgic images, magic prayers, and the daily occurrence of miracles.

Menen is a novelist, a distinguished novelist, and this has helped him to understand the way the people felt, to sense the epic tragedy of those four days, and to write about it perceptively and vividly. On the other hand this evident skill has somewhat weakened his work. The people he describes seem at times more like characters in a historical novel than real people. They speak in oratio directa, between quotation marks, in a somewhat awkward translation from the warm Neapolitan patois into a stiff and bookish English. Some of the dramatic incidents (true enough, I am sure) are so smoothly told that they seem contrived, invented, or at least embellished.

These shortcomings are not present in Naples ’44 by Norman Lewis. Lewis is also a novelist and writes very well, inconspicuously well. He too knows Italy well and speaks Italian, although he evidently cannot write the language. His Italian spelling is erratic, as has been usual in the work of Englishmen since the Renaissance, with the exception of Aldous Huxley. Naples ’44 does not seem to have been written retrospectively, built from fading memories or interviews with elderly survivors. It purports to be the actual diary of a year in and around Naples, as written at the time of the Allied occupation (a few weeks after the time of Menen’s tale) and barely edited. One goes on reading, page after page, as if eating cherries. In 1944, Lewis was a British intelligence officer whose vague assignments included searching for secret enemy agents or stray Germans left behind (he found none); fighting against the Camorra (the Neapolitan form of the Sicilian mafia) and against the dealers in the black market of Allied Armies’ stolen goods; investigating the suitability of Italian girls engaged to English military personnel (he found most of them highly unsuited); conducting a miniature battle with Italian bandits and one American deserter; and de facto governing Benevento, the city whose prince had once been Talleyrand. The book has the taste and smell of truth. Here is his description of Naples at the time:

Advertisement

It is astonishing to witness the struggles of this city so shattered, so starved, so deprived of all those things that justify a city’s existence, to adapt itself to a collapse into conditions which must resemble life in the Dark Ages. People camp out like Bedouins in deserts of brick. There is little food, little water, no salt, no soap. A lot of Neapolitans have lost their possessions, including most of their clothing, in the bombings, and I have seen some strange combinations of garments about the streets, including a man in an old dinner-jacket, knickerbockers and army boots, and several women in lacy confections that might have been made up from curtains. There are no cars but carts by the hundred, and a few antique coaches such as barouches and phaetons drawn by lean horses….

He describes a walk with Lattarullo, a Neapolitan friend:

We walked out together and faced this city which is literally tumbling about our ears. Everywhere there were piles of masonry, brought down by the air-raids, to be negotiated…. There was a terrible stench of shattered drains and possibly something worse, and the Middle Ages had returned to display all their deformities, their diseases, and their desperate trickeries. Hunchbacks are considered lucky, so they were everywhere, scuttling underfoot, and a buyer of the lottery tickets they offered for sale touched or stroked their humps as he made his purchase. A great collection of idiots and cretins including children propped against walls nodding their big heads. A legless little bundle had been balanced behind a saucer into which a few lire notes and a sweet had been thrown. In a matter of two hundred yards, I was approached three times by child-pimps, and Lattarullo, appropriately enough, was offered a cut-price coffin.

Naples ’44 has a collection of outlandish, almost unbelievable episodes which could only have happened in that city at that particular time, and of bizarre characters that few novelists could have invented. None of them could have existed anywhere else. Vincenzo Lattarullo (Lewis wrongly spells it “Vincente”), for example, is a distinguished gentleman, a lawyer who never had a client in his life. He manages to live on a legacy originally worth a pound a week but which has been devalued to a few shillings.

He stayed most of the day in bed…. He ate an evening meal only, normally composed of a little bread dipped in olive oil, into which was rubbed a tomato…. It appeared that Lattarullo had a secondary profession producing occasional windfalls of revenue. This had to be suspended in the present emergency. He admitted with a touch of pride to acting as a Zio di Roma—an “uncle from Rome”—at funerals. Neapolitan funerals are obsessed with face. A man who may have been a near-pauper all his life is certain to be put away in a magnificent coffin, but apart from that no other little touch likely to honor the dead and increase the bereaved family’s prestige is overlooked.

…The uncle lets it be known that he has just arrived on the Rome express, or he shows up at the slum tenement or lowly basso in an Alfa-Romeo with a Roman number-plate and an SPQR badge, out of which he steps in his well-cut morning suit, on the jacket lapel of which he sports the ribbon of a Commendatore of the Crown of Italy, to temper with his restrained and dignified condolences the theatrical display of Neapolitan grief.

Lattarullo said that he had frequently played this part. His qualifications were his patrician appearance, and a studied Roman accent and manner.

Some of the memorable episodes are scarcely believable to a reader who does not know Naples.

A week or two ago an orchestra playing at the San Carlo to an audience largely clothed in Allied hospital blankets, returned from a five-minute interval to find all its instruments missing. A theoretically priceless collection of Roman cameos was abstracted from the museum and replaced by modern imitations, the thief only learning—so the reports go—when he came to dispose of his booty that the originals themselves were counterfeit. Now the statues are disappearing from the public squares, and one cemetery has lost most of its tombstones. Even the manhole covers have been found to have a marketable value, so that suddenly these too have all gone, and everywhere there are holes in road.

Maybe portraying Naples (or any other city) at exceptional times, times of revolution, war, pestilences, looting, volcanic eruptions, or, as Aubrey Menen and Norman Lewis did, when all these calamities come together, is the best way to approach the truth about the city, just as there is nothing like earthquakes to reveal the character of people. Maybe a city at peacetime is deceitful, too good to be true. Neapolitans’ descriptions of themselves cannot be trusted, usually being too black or too rosy. Few visitors spend enough time in the ill-smelling slums, decrepit hospitals, and poor peoples’ miserable houses. Few interview Neapolitans dying of starvation or of mysterious diseases. Even sociologists and statisticians are at a loss to ascertain with some degree of accuracy the real number of unemployed. What exactly is an unemployed Neapolitan, anyway? Some may really be looking for a job; or may be living on the proceeds of some illegal activity or lavoro nero (moonlighting) which they do not wish to acknowledge, to avoid paying taxes and social insurance, while drawing unemployment compensation. Some may manage somehow to earn enough at the end of the day, perhaps by waiting around courthouses or government offices and offering themselves as witnesses to the signing of documents or testifying under oath to whatever the lawyer tells them.

Naples is a city of problems. It has one of the lowest standards of living in southern Italy, the largest percentage of unemployed in the country, surely one of the largest in Western Europe (how large it is difficult to say for the above mentioned reasons). Its sewers are archaic and inadequate, the sea is polluted and strewn with floating garbage. It has the largest infant death rate in Europe. It is vulnerable to epidemics of all kinds (cholera a few years ago, a deadly infantile virus infection a few months ago).

But all of these are merely varied aspects of one problem, the real problem. There is nothing mysterious about the many ancient ills of the city, nothing that a number of specialists, some ad hoc laws, and sufficient appropriations could not remedy. In fact specialists have been at work, laws were passed, funds appropriated in vast quantities for more than a hundred years. The city changed, to be sure, but the lives of the Neapolitans did not change perceptively. And this, of course, is the problem.

In 1882 cholera broke out. King Humbert I and his prime minister De Pretis rushed to the scene. They were shocked by what they saw. What the city needed, they decided, was an aqueduct, sewers, and straight boulevards cut through the maze of vicoli. (Baron Haussmann was the model of the time.) All this was done. In 1902 it was believed, correctly, that what Naples really needed was an industrial quarter. Naples was to compete with Milan and Turin. More laws were passed, money appropriated, and industrial plants rose in suitable zones.

Someone else thought Naples should imitate Nice. A row of luxurious hotels was built along the waterfront, where affluent foreigners could spend the winters. Some millionaires did, to be sure, but not enough to change the economy of the city. The Fascists later dedicated themselves to solve the problem once and for all. They erected public buildings, schools and hospitals, laid out more sewers, constructed new industrial plants, a straight autostrada to Pompei, and new modern quarters. In spite of their efforts, mostly nullified by the war and the Allied invasion, Naples was still fundamentally Naples.

After the war a Monarchist mayor and Christian Democratic cabinet ministers borrowed vast amounts of money to build more schools, hospitals, public buildings, housing projects for workers’ families, and modern industrial plants. Now the municipal debts are proportionately higher than New York’s. The city is governed for the first time by a Communist mayor who heads a coalition. He is honest, competent, active, capable, eager to prove that a Communist can be a better administrator than a man from more moderate parties. He too has been defeated by Naples. In fact, he is less able to stand up to popular or trade unions’ demands than any of his weak predecessors. The people know it and take advantage of it. When the vigili, or municipal police (to cite one example), won the privilege of going home on rainy days, all the mayor could do was stop the appropriation in the city budget for the vigili’s raincoats.

The problem, of course, is that Naples is fundamentally at odds with the Italian petit bourgeois world, whether Conservative, Social Democratic, Christian Democratic, or Communist. Practically all known formulas have been tried, all sorts of money spent. Some people now think that it is time to study the problem ab ovo to plan a future for the city more consistent with Neapolitans’ real desires, capacities, talents—not based on some foreign model. Many architects, for example, now believe that in the Mediterranean world of winter gales and summer heat the narrow and crooked vicoli are more functional than Parisian boulevards, and are better also from a sociological point of view, since every vicolo can be seen as a close-knit village with its own satisfactions. The people of Naples are among the liveliest, most flexible and alert of Europe. They are the city’s real wealth. Why not direct their energies, including those of the secret organizations, toward legitimate activities instead of forcing many of them to live clandestine lives?

What, then, is Naples? It is an Italian city, to be sure, but it is many other things too. Like Vienna, it is the humiliated, demoted capital of an old and glorious monarchy, seeking psychological compensations. Like Constantinople, Marseille, Venice, Dubrovnik, and Alexandria, it is an ancient Mediterranean trading center inhabited by merchants of all races. Like Vienna and these Mediterranean emporia it was always a natural bridge to the Levant, the Islamic world, and Asia. Perhaps this could provide one answer to its problems. Its vocation as a trait d’union to the East is suggested by the flourishing existence of an excellent Oriental language school which is many centuries old, possibly older than any other in Europe. When the first European ambassador was allowed to visit the Emperor of China (Lord Macartney, George III’s envoy to Ch’ien Lung), he had first to stop in Naples to pick up two Chinese interpreters. Nobody knew the language in Britain, France, or other Continental countries.

As economic and cultural relations with the East and the Islamic world are now becoming closer (by necessity as well as by choice) and will become even closer in the future, why not make Naples into a halfway point between the two worlds, a place where Arabs, Africans, or Turks will find trade and diversion? Of course this idea is already being discussed among the Neapolitans, who expect to be bitterly disappointed once again, as they have in the past.

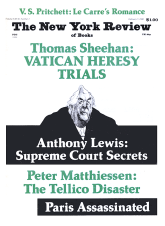

This Issue

February 7, 1980