Reading the reviews of the great Picasso exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art, I was struck by the emphasis most critics gave to Picasso’s private life and by their implication that only his biography would yield the true meaning of his work, John Richardson, a critic whom I respect and whose firsthand knowledge of the subject is formidable, even suggested, in a brilliant review in these pages, that a special effort be launched to gather every scrap of intimate detail while there are some with living memory so nothing would be lost that might provide clues to Picasso’s leonography.1 I was reminded of a curious essay by Gregory Battcock which served as the introduction to a little anthology of criticism he edited some years ago.2 He said that in the new art environment, the critic is now “a friend” of the artist who shares his style of life. Without intimate involvement of the critic in the artist’s life, the new art cannot be understood.

When I was young, in the 1940s and 1950s, such a view would have seemed blzarre, not only for the criticism of art but for poetry as well. Poetry was for the most part interpreted under the influence of the “new criticism” and modern art by the methods of formal analysis deriving from Roger Fry, Few serious critics wrote much about the sex lives of poets and painters, their homosexual leanings or unknown mistresses. We knew very little about T.S. Eliot’s private miseries and read his poems looking for meaning of another sort. Of course, there were useful biographies and important biographical criticism, such as Edmund Wilson’s essay on Dickens and Meyer Schapiro’s correction of Freud’s analysis of Leonardo da Vinci. But these were different from the collections of minutiae that have lately appeared, claiming to reveal, for example, the intimate secrete of Bloomsbury by reconstructing the sex lives of the Cambridge Apostles. The Scott Fitzgerald academic industry was in its infancy and the large apparatus constructed for Henry James was then concerned with the novels and stories, Lately, of course, it is his “secret life” that has been getting more attention than The Golden Bowl. Only the partisans of D.H. Lawrence seemed equally fascinated by his private life and work.

What excited us in the visual arts in those days was what we saw on Fifty-seventh Street at the galleries of Curt Valentin, Pierre Matisse, and Betty Parsons. Who knew or cared about Paul Klee’s private life? Or Mondrian’s? Or Matisse’s for that matter? Our idea of biographical information about modern artists was formed by the rather discreet accounts in John Rewald’s History of Impressionism and Alfred Barr’s monograph on Matisse, Reading those works, we did not, I believe, feel that we were missing any indispensable tool for interpreting the paintings. That the intimate life of the artist was somehow to be identified with the essential content of his art would not have occurred to us.

What has happened to our perceptions of art now? Or perhaps one should ask what has happened to art that it seems to require such biographical exegesis? Perhaps part of the answer can be found in the tradition of van Gogh’s ear. As Helene Parmelln3 has brilliantly argued, we have, since van Gogh, been paying for that ear over and over again in anxiety that the artist of genius may be working in obscurity, unrecognized, going mad. Every modern certified artist must therefore be accepted, promoted, devoured. Van Gogh’s ear has also led to the perception of the artist as a psychological case as well as to the idea of the artist as a celebrity. Pícasso himself, with Gertrude Stein as publicity agent, was of course the first modern artist who became an international celebrity—he became known, that is, to a huge public which for years had little or no idea of his work. Today it is Warhol and Rauschenberg who have made themselves into something like pop stars. Duchamp did his turn as a playful high priest or guru, Dali as society buffoon. But most of the major twentieth-century artists were never celebrities—think of Leger, Braque, Moore, Kandinsky, Miro, Matisse, Giacometti, de Kooning, etc.

For American postwar painting, however, van Gogh’s car was cut off again, one night in 1956, with the death of Jackson Pollock in a car crash. A surge of interest in Pollock and his friends soon took place; there was a growing sense that art of great importance had only partially been recognized while it was being created. This made the ensuing camp followers and “groupies” of the New York artists vow not to miss again. So every change of address and of lover have become art history and many young artists have acquired early fame, their private lives carefully documented in books like Calvin Tompkins’s Off the Wall, a life of Rauschenberg. Since Pollock himself was not around to perform in public, he became a creature of myth—the cowboy, the drunk, the instinctive “unconscious” dripper of violent expressionistic canvases. Nothing could be farther from the truth and, as with van Gogh and his ear, nothing appealed more to the public than sensational distortions, which were soon promoted by the new biographer-critic-friends of the artists. Pollock’s life produced a new genre, the soap opera of the modern artist, of which the purest example is B.H. Friedman’s Jackson Pollock: Energy Made Visible.

Advertisement

Feeding the demand I have been describing has been the growth of university art history departments with their relentless scramble for thesis material. In the rush to establish claims for a lifetime of digging rights, hundreds of doctoral candidates and ambitious junior professors have been dissecting and overdocumenting nearly every aspect of contemporary art. The “ad hominem” approach to understanding works of art has become increasingly popular in the art departments while, at the same time, a rival faction of academic criticism has carried traditional formal analysis to extravagant talmudic excess. Again Pollock provides us with the model for both extremes. The school of criticism led by Clement Greenberg and Michael Fried, in spite of its valuable insights, has sponsored the simplistic idea that Pollock’s most important historical function was as a stainer of the canvas who thus pointed the way for Helen Frankenthaler, Kenneth Noland, and Morris Louis, the younger painters who perfected his art and are the true legitimate modernists. On the other hand, newer and younger critics from the college art departments have been searching Pollock’s canvases for suggestions of birds, fish, horses, copulating couples, moons, mandalas, and snakes. Since Pollock’s death, it has been revealed that he had undergone Jungian therapy; and like some other New York artists, he created his own private mythology of visual symbolism.

William Rubin has effectively put the Jungians in their place in his powerful two-part article “Pollock as Jungian Illustrator—The Limits of Psychological Criticism,” in Art in America.4 However, the demolition of the Jungian claims has not daunted the search of Pollock’s paintings for connections with his private life. Francis V. O’Connor, the admired and respected colleague with whom I worked for seven years in preparing the Pollock Catalogue Raisonne, has recently departed from the neutral terrain of the cataloguer and advanced speculations on the meaning of Pollock’s work in an essay on the black and white series of 1951-1953.5 In these pictures he sees the artist’s use of black paint and his return to his early imagery as an attempt to cure a renewed episode of alcoholism. O’Connor attempts to “read” that imagery psychoanalytically by using as clues some bits of information about Pollock’s infancy and childhood. No one has greater command of the material than O’Connor, but his use of it does not for me ring true, nor does it illuminate the “meaning” of the black and white paintings which have been so important to postwar American art. One example:

Neither does one need Jung to suggest the archetypal fact of Pollock’s birth trauma; choked by the cord and, according to his mother, born “as black as a stove.” This fateful entrance into life is symbolized over and over in the imagery of the so-called “psychoanalytic” drawings and the work related to them of 1939-42 by the recurrent motif of a snake, or a rope-like shape, on or about the heads and necks of figures…. Thus Pollock’s mature painting method of pouring out line after line of paint through the air to the canvas surface can be seen, on at least one level of determination, as a continuous symbolic attempt to throw off the maternal stranglehold. The leonography of the black pourings provides ample evidence for such an interpretation.

This kind of interpretation leads us away from the paintings into byways that are both highly speculative and impossible to trace further or confirm. It reminds me of the quasi-scientific explanations of the pyramids of Egypt or Machu Piochu which presume ancient visits from outer space. It is as unhelpful for understanding the quality and significance of the works as are the specialists who explain away El Greco’s intensity by attributing his elongated forms to bad eyesight.

The most important evidence which confronts us is the visual fact of the paintings themselves. What do they look like? How are they close to, or different from, other paintings in their tradition or in the development of the artist himself? What, in the fullest sense, are they trying to communicate to us and what kinds of reactions do they produce in us? Whatever they denote of the artist’s psychological state of the moment is a subsidiary cause of their being and one of the less productive lines of inquiry because it can only be guesswork.

Advertisement

Of course, as we have all been told so often, the experience of visual art cannot be translated into words; but gifted critics at various times have come very close to doing so. The best critics, for me, are those who describe the work of art in such a way that one can go back to it and see a great deal that one missed the first time. It is not that paintings cannot be autobiographical, as indeed they sometimes are in the cases of Picasso and Pollock. But that autobiographical content is incidental to what makes them satisfying and occasionally great. Many bad paintings are also autobiographical. To insist relentlessly on the biographical is to avoid precisely the considerations which distinguish the good from the bad in visual art and to avoid as well the qualities which often can be perceived only visually. We might even say that the meaning in any great work of art is the element which reaches beyond particular biography and becomes a larger statement. (When Pollock says: “Painting is a state of being. Every good artist paints what he is,” he does not in any way contradict this.)

To return to Picasso, what I missed in the current emphasis on identifying his mistresses and wives, his periods of sexual satisfaction or unhappiness, and the friends or courtiers of each phase, was his sardonic account of the decline of Mediterranean civilization as a drama in which the artist is cast sometimes as hero, sometimes as chorus, and sometimes as “deus ex machina.” A battle between good and evil takes place in many of Picasso’s complex works and in others, including his portraits, still lifes, and even landscapes, there is a tragic sense that is sometimes unbearably moving. At the same time Picasso, always aware of the problems of the picture surface, is performing in the theater of the eye itself and he cavorts like a dazzling acrobat defying gravity, risking a fall but usually landing on his feet.

Great paintings, drawings, and sculpture offer us an intense, even an ecstatic experience if we are able to see them for what they are. We risk the loss of that experience if our approach to their meaning becomes reduced to a single-minded search to identify personal episodes. To know such facts about great artists can be valuable and interesting, but they are not the essence or the meaning of their work.

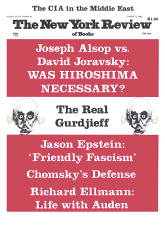

This Issue

October 23, 1980

-

1

The New York Review, July 17, 1980.

↩ -

2

The New Art, A Critical Anthology (Dutton, 1973).

↩ -

3

Art Anti-Art, Helene Parmelin (Humanities Press, 1977).

↩ -

4

November 1979 and December 1979.

↩ -

5

For the exhibition. “The Black Pourings 1951-1953.” Institute of Contemporary Art, Boston, May-June, 1980.

↩