As the still center of Bloomsbury, Vanessa Bell has remained something of a mystery. The volumes of Bloomsburiana have multiplied, the major and minor characters have been anatomized, but still her figure has stayed obscure. We have seen her chiefly through her sister’s jealous, devoted gaze; but others tried their hands at describing her. “Monumental, monolithic, granitic,” wrote Leonard Woolf; “It was the strange combination of great beauty and feminine charm with a kind of lapidification of character and her caustic humour which made her such a fascinating person.” “She was not at all dogmatic,” said Kenneth Clark, “but she never relaxed her standards, and in a quiet, hesitant voice would expose false values and mixed motives. I was devoted to her, and when asked to do something questionable, I would think to myself ‘What would Vanessa say?”‘ In a poem about her, her son Julian wrote of her “calm of mind,/…Patient and sensitive, cynic and kind.” Roger Fry, deeply in love with her, wrote of the atmosphere of peace with which she surrounded people:

I imagine all your gestures and how you’ll be saying things and how all around you people will dare to be themselves and talk of anything and everything and no idea of shame or fear will come to them because you’re there and they know you’ll understand. And then I think of how beautifully you’ll be walking about the rooms and how you’ll take Quentin on to your knee and how patient you are and yet how you are just being yourself all the time and not making any huge effort just living very intensely and naturally…

A madonna-like serenity is the theme of the descriptions of Vanessa. Her sister spoke of her “rich, soft nature.” When she was a child, her nickname was “The Saint.” But this surface overlaid powerfully deep feeling, as Leonard Woolf also saw: “The tranquillity was to some extent superficial; it did not extend deep down in her mind, for there in the depths there was also an extreme sensitivity, a nervous tension which had some resemblance to the mental instability of Virginia.” Her mysteriousness was that automatically attributed to someone graceful and rather silent; in actual fact she was no woman of mystery, being straightforward, literalminded, and hard working. But she was profoundly reserved; and became more so as the odd shape of her life developed.

The two sisters Vanessa and Virginia divided out the world between them, each annexing a talent and a style. To the events of their early life Virginia reacted with terror and violence, Vanessa with withdrawal into her marmoreal calm; she was, after all, the eldest child, the protector of the tribe. Those events in all their tragedy are now well known to most people because of the great interest in Virginia Woolf’s life. The Stephen parents had both been widowed before their marriage; there were half-siblings and, on the Stephen side, a bizarre retarded child—in all, eight children.

The major tragedy was Julia Stephen’s death at forty-nine, when Vanessa was sixteen. Virginia, fourteen, had a breakdown; Leslie Stephen, always a difficult man, became yet more reclusive, melancholic, and irritable. Stella Duckworth, the elder half-sister and devoted to her mother, took charge of the big household as best she could; then two years later, still in her twenties, she died suddenly. At eighteen Vanessa headed a household of three younger children, two half-brothers, and an elderly father given to weekly rages over the household accounts and storms of sobs. A few years later, the younger brother Thoby died of typhoid. No wonder Vanessa wrote, after reading an essay by Virginia about their early life: “I felt plunged into the midst of all that awful underworld of emotional scenes and irritations and difficulties again as I read. How did we ever get out of it? It seems to me almost too ghastly and unnatural now ever to have existed.”

They got out of it, chiefly, through Leslie Stephen’s own death, welcomed by Vanessa as quite simply a relief, although it led Virginia to another breakdown. The laden atmosphere of the Bayswater house was broken up and the four young Stephens took a house in unfashionable Bloomsbury, where walls were painted pure white and knick-knacks got rid of. Gradually they began to evolve the social circle that was to become the nucleus of Bloomsbury. For up till then the social setting of the two girls, “coming out” as they reached eighteen, had been odd. With no mother and effectively no father, to launch them among compatibles, Vanessa had been pushed unwillingly into a social round by the Duckworth half-brother. Dumbly she had rebelled; the two beautiful Stephen sisters had sat silent and forbidding in polite society, and all their lives were to dread dressing up—Vanessa, with the arrogance of the naturally beautiful, becoming known for her costumes of odds and ends pinned together with safety pins.

Advertisement

Now at last they began to have a young circle of their own, where talk was free and their brothers’ Cambridge friends made themselves at home. All was to be different from the Bayswater days: they would do without table napkins! have coffee after dinner instead of tea at nine! It was as if, Vanessa was to write, they had suddenly stepped into daylight from darkness. Virginia wrote, Vanessa painted. Nevertheless, where marriage was concerned they were still in an odd position, since “buggery” (as they called it) was the fashion among the Cambridge set. When Vanessa at twenty-seven married Clive Bell it may also have been, Frances Spalding suggests, on the rebound from her brother Thoby’s sudden death.

The special Vanessa Bell reserve may be what makes it hard for her biographer to explain quite what went wrong so soon with the Bell marriage and then with the affair with Roger Fry—a much more solid and devoted figure than Bell. Clive Bell was no faithful husband; but several years after the marriage Vanessa was still writing to him affectionately: “I have been meditating on marriage! …It is like being always thirsty and always having some delicious clear water to drink. You do make me astonishingly and continuously happy.” The curious incident, forever unsettling to both sisters, when Clive briefly and perversely decided he had been in love with Virginia all along, cannot have been negligible. Roger Fry she came to know in 1910, when he was forty-four and she thirty-one and the mother of two boys. His wife was mentally ill and eventually committed to a home, and he fell deeply in love with her. Vanessa, true to Bloomsbury rationality, was aware of no resentment against Clive but simply added Roger to her life: “[You] will make everything better for me and spoil nothing.”

But some time around 1913, when the Omega Workshops were founded under the direction of Vanessa, Roger Fry, and Duncan Grant, the relationship that was to dominate the rest of her life began to emerge in all its strength. Where Fry was serious, responsible, and considerably older than her, Grant was six years younger, an irresponsible elf—and nine-tenths homosexual. Frances Spalding constantly returns to the sensuality “exuded” by Vanessa, but nevertheless she rejected two sexually active men to spend most of her life devoted to a homosexual who caused a fever of suppressed fear that he would leave her for one of his lovers.

Perhaps painting was more important to her than sexual love. She had gone on painting right through the years when her sons were most absorbing (the bohemian life in those days included nursemaids and cooks), and now she and Duncan were to paint side by side in the same studio, without competition, for the rest of her life. Her work had undergone much change since she started at the Royal Academy schools under the influence of Sargent and Charles Furse; the two post-Impressionist exhibitions of 1910 and 1912 that Roger Fry organized, though execrated by the critics, had stunned and invigorated her. She was loyally committed to the Bloomsbury doctrine of significant form that Clive Bell developed in his book Art, but never did more than dally with pure abstraction; nature itself was too rich and interesting, she told her son in later life. With quite genuine humility, she always felt that Duncan outstripped her as an artist.

In 1912 she and Clive had removed to the country; Clive, Duncan, and Roger all revolved around her as center of the amiable, relaxed household, but Duncan emerged as the companion to whom she held fast. In spite of the tortuous complications of his love affair with David Garnett, she had a daughter by him in 1917, which Bell was genial about passing off as his own. “I think of marrying it,” wrote Garnett on the day of the birth; “When she is twenty I shall be 46—will it be scandalous?” Twenty-four years later the two were married.

The great horror of Vanessa’s later life was the death of her adored elder son Julian in the Spanish civil war. After that she was perhaps too numb to feel fully her sister’s suicide in 1941, for Frances Spalding says little about her reaction to it. A visitor to her house Charleston in the 1940s, however, describes it as a house of ghosts, Vanessa silent and looking years older than her age. The sunny days were not completely over, though, for her grand-daughter has described happy times spent there, dressing up in Omega curtains and playing at weddings.

Clive was a witty and erudite conversationalist of great charm and intelligence. Duncan was an enchanting and eccentric individual. Nessa loved them both. She gazed from one to another with her beautiful blue-grey eyes and let the smoke drift slowly from the gauloise which she took with her after dinner coffee. At certain intervals she would murmur “How absurd.”

And she never, up until the end, ceased to paint, though the peak of her and Duncan’s success had passed in the 1930s and she produced much that was mediocre. Frances Spalding, as art historian and biographer of Roger Fry, enriches the book with some shrewd analysis of the course of her painting, although her suggestions about its relation to childhood deprivation are more dubious.

Advertisement

“How absurd.” Was it absurd, the Bloomsbury ethos of reasonableness in all situations, of always being “civilized”? It facilitated much that was shapely and creative and tolerant, but by denying the unruliness of the irrational it could also send things awry. To achieve her calm it is clear that Vanessa Bell had to limit and suppress herself. “Oh I daresay Vanessa is a more perfectly and harmoniously developed being but perhaps she’s a demi-god and we are only human,” wrote Fry pettishly later, perhaps thinking of his rejection. “Lapidification” of character was Leonard Woolf’s admiring term: noble as marble perhaps, but stony too. Yet her suppressed feelings for Duncan Grant were such that he wrote that he dared not show her any emotion for “I feel that if I showed any, it would be met by such an avalanche that I should be crushed.”

Where things did go awry was in the case of Angelica, Grant’s daughter. Not only was she—perhaps understandably—not told of her parentage until she was nineteen, but this daughter of the bawdy, liberated Vanessa grew up sheltered from all the facts of life. The emotional convolutions of the Stephen/Bell/Grant family, apparently so amiably settled, came to roost here. Being “civilized” failed when it came to explaining the roots of the situation to a sheltered and indulged girl, and the mother-daughter relationship remained strained. “I really didn’t escape from her until I was over forty,” Angelica Garnett has written. As her mother had, Angelica rebounded from the tragic death of a brother into a love affair and marriage—with one of the chief of her father’s ex-lovers.

In old age—she lived to eighty-two—Vanessa Bell was gentle, melancholy, aloof with strangers, much loved by intimates. The eldest of the Stephen clan, she had outlived them all, as well as her elder son. But Duncan—still able to cause pain with his fancies for lovely young men—was her constant painting companion, there were many friends left, and there were six grandchildren. She continued to run her Omega-decorated house competently—with the help, let it be noted, of a devoted and underpaid couple. (She did title one of her pictures “Interior with House-maid,” but might she not as easily have called one “Interior with Duchess”?) Invitations to grand dinners she refused on the grounds that she had no evening clothes. Bloomsbury, meanwhile, was becoming a subject for the social historians; but she did not take kindly to researchers and academics. When she died peacefully, in 1961, the cliché “end of an era” was for once true. Frances Spalding’s carefully researched biography leaves one with a hint of dissatisfaction, a tinge of frustration at finding its subject still just out of focus, as though the different aspects of her never quite coalesce; but perhaps this is something inherent in Vanessa Bell’s rare and elusive nature.

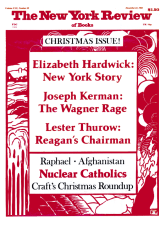

This Issue

December 22, 1983