An armored black Zil draws up at the ceremonial entrance to Windsor Castle. Out gets Mr. Gorbachev. He comes forward to meet the Queen. As he does so, he anxiously tucks his scarf into his black overcoat, a gesture equivalent to making certain his fly isn’t undone. This, apparently, is a standard reaction on meeting royalty. People are taken up short or struck dumb, or hear themselves muttering the most embarrassing imbecilities. The then American ambassador to the Court of St. James, Walter Annenberg, was immortalized on television—in the first Day-in-the-Life-of soap documentary on the royal family—muttering interminable convolutions about the “refurbishments” going on at his residence. Why should people be quite so awed? The Queen of England is in many ways an extremely ordinary woman; none of the royal family has the obvious characteristics of a star, with the possible exception of the mindless Diana. There is nothing much to admire in any of them other than their royalty. That is the point. It puts them in another league from mere celebrity.

The only interesting thing about them is that this should be so. What is their attraction? Why do our popular newspapers, which know their market, endlessly paste their front pages with royal pap? In early June, the story that drove the aftermath of Tiananmen Square from the headlines was that the Queen had given special permission to eight-year-old Zara Phillips, Princess Anne’s daughter, to attend the opening of Royal Ascot although the rules strictly forbid children younger than sixteen from the Royal Enclosure.

The Times is not above this rubbish, reporting on its front page, “Normally the rule governing children in the Royal Enclosure is iron.” It went on:

According to the rules, girls must wear a dress, but a hat is optional. Zara opted for a straw hat, tiny floral-print dress, and white gloves, and studied her race card intently as she walked with the Princess Royal [Anne] to and from the paddock:

We also learned,

The Queen, with her long experience of the hotter corners of the Commonwealth, appeared at ease in the blistering temperature while the Princess of Wales [Diana] sheltered under the enormous flying saucer brim of her hat. Less exalted women tended to keep their hemlines short and their shoulders bare under the shade of broad hats.

Hats are an important aspect of the royal magic, as Tom Nairn—whom we will come to in a moment—records. He quotes from a book called 100 Years of Royal Style to the effect that three or four months is not an uncommon length of time for the making of one of the Queen’s hats, which are famously awful, by the way. “This is time well spent, for, in the iconography of dress the hat is surely the most important item. It not only denotes authority, it is, in Royal terms, a substitute for the ultimate symbol of power: the crown.” There is no limit to this sort of stuff and, it would appear, a virtually limitless market for it. Diana or Fergie (Duchess of York) on the covers of the big circulation women’s magazines can boost sales by as much as 20 percent. We have one monthly magazine called Majesty which is simply a compendium of miscellaneous information about the royals, their servants, their retinues, their friends, combined with comprehensive listings of their forthcoming engagements, a kind of manual for royal groupies. It sells 150,000 copies a month. Entire sections in bookstores are devoted to “Royalty.” Memorabilia of all kinds are big business. The Queen is currently appearing on the London stage in a somewhat flimsy play by Alan Bennett. It is booked to capacity. When Prunella Scales comes on—in pale royal blue, simple brooch, three strings of pearls—there is a round of respectful applause. It is her.

Walter Bagehot located the secret of monarchy in mystery. Today the mystery is the mystery. His famous advice was “We must not let in daylight upon magic,” advice that the royal family in recent times has followed assiduously while seeming not to. Bagehot was writing at a time when the reclusive widow, Victoria, was deeply unpopular. In 1864 a notice was fixed to the railings of Buckingham Palace announcing, “These commanding premises to be let or sold, in consequence of the late occupant’s declining business.”1 “To be invisible,” wrote Bagehot, “is to be forgotten.” Her disappearing act, he believed, had done more harm to the institution of monarchy than all of the profligacy and frivolity of her predecessors. Bagehot cared because he attached much importance to the symbolic role of monarchy. While modernizing what Bagehot called the “efficient parts” of the Constitution, the middle classes, after the Reform Act of 1832, had prudently left in place its “dignified parts,” the monarchy and House of Lords. Britain by 18652 was what he called a “disguised Republic,” which worked well “because the mass of the English people yield a deference rather to something else than to their rulers. They defer to what we may call the theatrical show of society.” Meanwhile, the “real rulers” (the middle classes) were “secreted in second-rate carriages; no one cares for them or asks about them, but they are obeyed implicitly and unconsciously by reason of the splendour of those who eclipsed and preceded them.”

Advertisement

With considerable prescience, in view of the unpopularity of monarchy at the time, Bagehot predicted “the more democratic we get, the more we shall get to like state and show, which have ever pleased the vulgar.” The British monarchy of today is in large part a phenomenon of the mass society, in a very real sense; the press created it. First the yellow press, then radio, now television provided a mass audience for the ritual which Bagehot had described and what a historian of Venice has called the “artistic mastery of government by pageantry.” 3 Queen Victoria’s Golden Jubilee, in which she took part only with the greatest reluctance, may have marked the beginning of the popular monarchy. Her son, Edward VII, had a talent and a taste for pageantry: it was he, for example, who revived the state opening of Parliament, which today is one of the great ceremonial events on the royal calendar. His funeral was an immensely popular event and became the model for later royal funerals.

George V described himself as “a very ordinary sort of fellow,” which he was; in the mold of the Windsors,4 he was an aristocrat devoid of intellectual interests or attainments. This ordinariness, with its emphasis on family life, became an important element in the magic of the popular monarchy. In Royal Family, the 1960s television documentary which made the then US ambassador Walter Annenberg a national joke, one of the more riveting pieces of dialogue was the Queen’s remark that there was a little too much vinegar in the salad for a Sandringham picnic. Uncommon common touches of this kind are all that is required to sustain the myth of ordinariness.

Bagehot’s warning against letting the daylight in on magic plainly did not apply to television cameras: they here become an essential part of the illusion. But it was George V who first put the monarchy on the air with his Christmas Day broadcast of 1932, which was beamed throughout the empire. This became an immensely popular event. And it was John Reith, the first director general of the BBC, who saw the potential of radio in presenting “audible pageants.”5 When, at his Silver Jubilee in 1935, George drove through the East End of London—a district plagued by unemployment, poverty, and political violence—they cheered him hollow. “I had no idea they felt like that about me,” he said. “I am beginning to think they must really like me for myself. I am just as much King in Whitechapel as in Whitehall.”

A measure of the now invincible popularity of the monarchy was the ease with which in 1936 it survived the abdication crisis. Respectability had become so important an ingredient of the popular monarchy that it was unthinkable that the new king, Edward VIII, could “marry the woman I love”—an American divorcée—and remain king. Edward’s huge personal popularity as the prince who had visited the unemployed miners of South Wales and said “something must be done” departed to the south of France with him and Mrs. Simpson. The fears of the establishment proved quite unfounded; the monarchy as an institution survived, untarnished and unscathed. The King was gone, long live the King. His stammering younger brother, George VI, would do just as well, and did. Nairn tells us that it was the abdication that first drew the attention of intellectuals to the immense popularity of the monarchy, remarkable at such a time of social division and political turmoil.

Nairn, in a book that I have to say I have found virtually unreadable in digressive prolixity, labored allusiveness, and intellectual pretension, although others have admired it, makes much of this strange British cult of royalty worship. “Are we all mad?” he not unreasonably wonders. Not only does he wonder at the phenomenon but takes it seriously. A republican himself, and unorthodox Marxist, he attributes to the fascinating power of monarchy the failure of Britain to make of itself a modern nation. It has fobbed us off with an ersatz sense of nationhood, leaving us a deformed and retarded society with no sense of citizenship equivalent to the American or French. Nairn believes as others have argued, on the right6 as well as on the left, that the middle classes never completed their triumph in Britain, allowing much of the ancien régime to survive into the Industrial Revolution and beyond. Part of that surviving aristocratic order was the monarchy, which he, like Bagehot for similar reasons, regards as a crucial prop to the system. Nairn places it at the core of our rottenness.

Advertisement

It is a thesis as hard to disprove as to prove. Many think that there is something not quite healthy about our obsessive, humiliating worship of such unheroic heroes. How do we manage to make quite such a national soap opera out of such a boring and unglamorous lot? But it is by no means clear, or not to me, that this has much to do with whatever is taken to be the defects of our political system. Moreover, it must be just as likely that royalty worship is a reflection of our society, in which the monarchy has happened to survive in the form that it has, as that British society has formed around the survival and peculiar character of the monarchy. Nairn in his foreword implies that his choice of title, The Enchanted Glass (the phrase is Francis Bacon’s), derives from Charles de Gaulle’s address to the Queen in 1961 as “the person in whom your people perceive their own nationhood, the person by whose presence and dignity, the national unity is sustained,” which, incidentally, may say as much about the general’s quasi-regal pretentions as about the British monarchy. Be that as it may, the case for taking the monarchy seriously rests chiefly on two propositions. One is the theory holding that deference to authority is generally strengthened by the monarchy’s existence, the second, that the royal family is important in perpetuating the class system in which British politics remain firmly rooted. So let us consider these.

At one level deference is simply another form of fawning, and there is plenty of that. According to the author of Dreams about Her Majesty the Queen and other members of the Royal Family, which Nairn cites, up to one third of the population has dreams about the royal family, of which the most archetypal is tea with the Queen, whether a cuppa at Buckingham Palace or her popping round for one. (The incidence of dreams about sex with the Queen we are not told.)

But it is a big jump from such pathetic fantasy, via—inevitably—the works of Theodor Adorno among others, to the conclusion that acceptance of royalty’s place is the badge of acceptance of one’s own lot. Adorno, in any case, as I remember, related his theories of relative deprivation to peer groups: the American private soldier resented the privileges of the sergeant more than the general’s. The royal family, by much of Nairn’s own account, lives on a cloud of fantasy so high above the power relations which touch on people’s lives that I doubt that deference, in any real political situation, has much to do with it. How else do we explain the growing popularity of the monarchy through periods of social and political unrest, not only—as we have seen—the Twenties and Thirties but also the Seventies and early Eighties? Better still, how do we explain the great wave of industrial unrest, and the accompanying growth of violence, during the last two decades when the royal family was fawned upon as never before? If, as Nairn would have it, it is the monarchy that “binds the state together,” its cement cannot have been very strong in the Seventies, when the social classes and constituent nations were tearing one another apart against a background of rampant inflation; and yet never had the fascination of royalty been greater.

The notion that the royal family was somehow at the same time both the pinnacle and the linchpin of the class system had more force in the Fifties than it does today. Nairn harks back to criticisms then made of the Queen for her voice and accent, narrow circle of friends, and even narrower range of interests, largely confined to horses and Corgi dogs. In short the Queen was too upper class, too “county.” County, that is, as opposed to town or, worse still, trade: county conjures up images of agricultural shows, hunting and shooting, the traditional country pursuits of the landed aristocracy. All this was true; that was the time of Look Back in Anger, and class was what the angry young men were most angry about. But it was society that changed, not the monarchy; the royal family went on exactly as before. Moreover, it clung to its way of life with ruthless self-interest, calculating the survival of its privileges and immunities, self-preservation its overriding goal.

In order to do this it took Bagehot’s advice, still keeping the “daylight out” while letting the spotlight in when it would serve to do so. Thus during the thirty years since the angries, Britain became a more classless society than before, while the royals became the more loved for their classiness. The “Queen’s English” today is scarcely spoken, except by the Queen. While many of the stiff formalities of English society have been abandoned Prince Charles, for all his groping to articulate popular resentments of modern architecture and his whining about his royal situation, expects his friends to call him sir or, more familiarly, “Wales,” but never Charles. The snobbism that once attached to “the Royals” has largely dried up; today fashionable people are more likely to be snobbish about them.

Britain may remain, by American standards, a class society—lacking an overarching notion of citizenship—but it is not the same class society that it was. As a Tory wit noted, the Conservative party under Mrs. Thatcher is no longer the party of estate owners but the party of estate agents—i.e., realtors. One of her henchmen, Norman Tebbit, says that Prince Charles worries about the unemployed because he is unemployed himself. The aristocratic ethic and way of life, which are what the royal family represents, and ruthlessly preserves for itself, have not much place in Mrs. Thatcher’s meritocratic and plutocratic Britain.

No wonder the Queen does not like her. Or so it is said, although there is no evidence on this subject beyond hearsay and gossip. However, London, from time to time, buzzes with tales of the Queen’s disdain for her prime minister. In particular there were tales of a dinner party last year at which the Queen held forth on the subject in haughtily scathing fashion. It rings true. The Queen is undoubtedly a Tory but probably what Mrs. Thatcher calls a “wet.” The English aristocracy, unlike its continental cousins, has seldom been reactionary; more usually it has been paternalistic and has used the rhetoric of “One Nation,” if only as the best means of avoiding the guillotine or the lamppost. Its survival is owing largely to this talent for accommodation through amelioration.

Mrs. Thatcher is a departure from the mainstream of the Tory tradition in that her brand of populism is abrasive and divisive. The Queen may well not like to see “her people” treated in this manner. It is said, for example, that she became alarmed at the level of unemployment and did not like the spirit in which Mrs. Thatcher confronted and beat down the miners. It also got around that the Queen, who takes very seriously her ritual headship of the Commonwealth (which provides her with much opportunity for foreign travel), was greatly upset by Mrs. Thatcher’s adamant refusal to enact serious sanctions against South Africa, an issue that for a moment threatened to break up the Commonwealth. In the Queen’s firmament Mrs. Thatcher is not her only prime minister. But all this is really not much of an advance on the gossip about “the marriage”—the wimp and the bimbo—or the yobbo Yorks (Andy and Fergie) or Anne and her equerry: for it doesn’t matter what the Palace’s relations with Mrs. Thatcher are, and it doesn’t matter because the monarchy—Nairn passim—is of little political importance.

So what is it then? What is its secret, its magic? Surely not wealth, although that is immense and compounded by exemption from income tax. Blood? The House of Windsor is not exactly an advertisement for genetic selection; its combined educational attainments would disgrace a poor slum school. Celebrity is not the explanation, for royal worship is of a different order from star worship. A political and economic power it certainly isn’t, for, apart from Charles’s effects on architectural commissions, the monarchy has none. The monarchy, I suspect, is the reflection of a deeper cult, a fantasy so far removed from all reality that it has become autonomous, largely unconnected with the changes in the spirit of the times, immune to political or social fashion, an expression, perhaps, of a continuity embedded in the social psyche of the British, now taking the form of the soap opera in our dreams.

This Issue

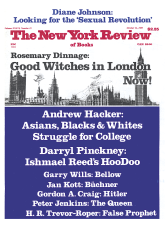

October 12, 1989

-

1

Quoted by David Cannadine in The Invention of Tradition, ed. Eric Hobsbawm and Terence Ranger (Cambridge University Press, 1983), p. 119, a useful account of the evolution of the ritual monarchy.

↩ -

2

Bagehot’s English Constitution was published in that year. The 1963 Penguin edition has an excellent introduction by Richard Crossman.

↩ -

3

Frederick C. Lane, Venice: a Maritime Republic (Johns Hopkins University Press, 1973), p. 271.

↩ -

4

It was George V who in 1917, in deference to the patriotic spirit of the war, changed the name of the house from Saxe-Coburg to Windsor.

↩ -

5

Cannadine, The Invention of Tradition, p. 142.

↩ -

6

Notably Jonathan Clark in English Society 1688–1832 (Cambridge University Press, 1985) and Revolution and Rebellion (Cambridge University Press, 1986).

↩