In response to:

From Hirohito to Heimat from the October 26, 1989 issue

To the Editors:

Since unflattering reference is made to my activities in two separate articles in your October 26 issue, I believe some words in my defense are in order.

Ian Buruma takes the liberty of using me as a pad to launch himself into his essay, “From Hirohito to Heimat,” placing me in the unsavory company of German and Japanese revisionists. Of course, he hastens to note that he does not “mean to imply political or moral parity between Weiss, Reitz, and Japanese revisionists,” but that self-serving qualification notwithstanding, he proceeds to construct his analogy. “What the rabbi, the German artist, and the Japanese revisionists have in common,” writes Buruma, “is an exclusive idea of history, often symbolic, mythical,” and so on. I’m afraid it simply has not penetrated Buruma’s fine sensibilities that what brought our group to the Carmelite convent in July 1989 was precisely to keep the hands of the myth-makers, symbol-mongers, and revisionists of every stripe off Auschwitz.

By stationing praying nuns at Auschwitz and by erecting the most striking of its symbols there, a 24-foot high cross, the Catholic church has engaged in one more campaign to mythologize its role during the Holocaust, to imply moral intervention and concern when there was only indifferent silence. For the sake of the truth and the history that Buruma insists in words that he honors, and that we honor in our deeds, we came to demand that Auschwitz be maintained in all of its brutal purity, free of myth and free of symbol, that it be maintained unblemished for what it was—a killing center where 85 percent of those murdered were Jews.

Particularly disturbing is Buruma’s style of gliding into his argument, glancing over certain crucial points as if they were not as central as, indeed, they are. The Carmelite convent, he says, is in “an old warehouse outside the main Auschwitz camp.” The implication is, Why such a fuss over “an old warehouse” that isn’t even inside the camp? In fact, this “old warehouse” was the storage center for the canisters of Zyklon B gas used to suffocate the victims. Moreover, at the specific request of the Polish government, Auschwitz, including Buruma’s “old warehouse,” is included in the 1972 United Nations Convention for the Protection of the World Cultural and National Heritage, an agreement designed to preserve intact sites of outstanding cultural and national interest. Placing nuns in this place of horrors and erecting a cross there is in violation of the U.N. agreement.

Buruma proceeds to observe smugly that the promised interfaith center, “though delayed, is now likely to be built, but in the meantime Weiss and some highly insensitive Polish prelates turned the affair into an unseemly battle over the symbols of martyrdom, degrading the memory of all those who died at Auschwitz, whether Jewish or gentile.”

First of all, the likelihood that the center would be built did not evolve casually out of thin air. A demonstration such as ours was needed, it seems, to bring the matter of the convent starkly to the attention of all men and women of conscience and good will. The decision to construct the interfaith center did not come “in the meantime,” but after our protest and the “unseemly” (our apologies for offending Mr. Buruma) chain of events it precipitated, including Cardinal Glemp’s transparently anti-Semitic pronouncements. (To call the Polish prelate “insensitive” is putting it mildly, except perhaps for the oh-so-sensitive Buruma, for whom the word is horrible enough.)

For Buruma to accuse me of “degrading the memory of all those who died at Auschwitz” is beneath contempt, and, quite simply, unforgivable. Buruma and his “upper-middle-class Jewish grandparents” might “wince” at our tactics, which, by the way, consisted primarily of non-violent prayer and studying Torah, certainly not “screaming at Polish nuns,” as Buruma says. For my part, I’m quite resigned to the wincing of the academics in their university tweeds. As I see it, we are on our way to accomplishing our goal. After months of silence, the Vatican has finally conceded that the nuns should relocate to an interfaith prayer center to be built in accordance with a 1987 Geneva agreement between the Jewish and Catholic leaders. Although no timetable has been given, the move is likely to happen. For the meantime, it appears, that Auschwitz will be spared at least one onslaught by revisionists, myth-makers, and symbol-concocters.

As for Robert I. Friedman (“The Secret Agent”), once again he pulls that tired little paragraph out of his computer memory bank, asserting my support, and the support of some members of my family, for Jonathan Pollard’s cause. This time, though, he takes the trouble to vary that paragraph a little by appending an identifying clause: “Rabbi Avi Weiss, the leader of the group that staged a demonstration at the Carmelite convent at Auschwitz this summer….” (Oh, that Avi Weiss!)

It’s no secret that I, along with many others, believe that the degree and severity of punishment meted out to Jonathan Pollard and the sentencing of his wife, Anne, to any prison term at all are so unprecedented and extreme that one can only speculate what particular animus inspired such vindictiveness against this couple. This has always been my position, even in the early days of the Pollard sentencing, when Jewish leaders timidly distanced themselves from the accused. Now, of course, the tide is turning in the American Jewish establishment and in Israel. There’s an increasing sense that the Pollards have been the victims of a peculiar and grave injustice, and a momentum is growing in the Jewish community to come to their assistance.

We have almost succeeded in the matter of the convent, and there are signs of movement in the Pollard case, too. If I am the kind of man who, according to Buruma, “gives Jews a bad name,” and if my style of non-violent advocacy of the Pollards and of the campaign to keep Auschwitz symbol-free sets off an epidemic of wincing among Buruma, Friedman, and friends, then so be it.

Avraham Weiss

Rabbi

Hebrew Institute of Riverdale

Bronx, New York

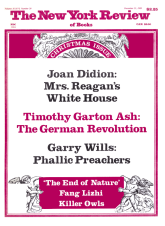

This Issue

December 21, 1989