These two famous Civil War memoirs, Grant’s published in 1885, Sherman’s in 1875, are linked in many ways, including the close relations of the authors and the common subject matter of their books. It is well that they are revived and republished simultaneously in the Library of America series, for both are still readable and quite worth reading. The praise lavished upon them for their literary merits over the years has probably not been uninfluenced by the high place the old heroes had won in national history. Gertrude Stein and Edmund Wilson were enraptured by Grant’s prose, and Mark Twain compared his book with the Commentaries of Julius Caesar—though admittedly Twain was Grant’s publisher. Whatever their relative literary merits may be, few would dispute their claim to first place on the vast shelves of Civil War memoirs, the two with which to start—at least among those from the Union side.

Differences between the two books are comparable to the differences between their authors. Grant’s book is guarded and even-toned, reticent or dispassionate about himself, generous with rivals, silent about his critics, and respectful—if not invariably fair—toward “the enemy.” William Tecumseh Sherman (“Cump” to his family) is offhand, forthright, outspoken, and intensely personal; he has a flair for action narrative. He takes the reader right up to the firing line with him. Better educated than his commanding officer, Sherman was more confident and comfortable with words and their uses. Part of Grant’s restraint may have derived from a shaky command of grammar and spelling: “Good buy, Ulys,” he signed a letter to his spouse of twenty years, and issued an order about the same time for the arrest of the editors of the Memphis “Bulliten.” The manuscript for the Memoirs must have presented a challenge to the copy editor.

This is not to lend credence to claims and rumors about ghost writers. U.S. Grant wrote this book. It was the astonishing circumstances of the writing that encouraged the rumors. Faced with terminal cancer and little time left to live, and faced also with virtual bankruptcy and a family he would leave without means of support, he took Mark Twain’s advice and went to work. He completed the manuscript in eleven months, nearly a thousand pages in print. He died a week later, on July 23, 1885. It was probably the most heroic achievement of his life, not excluding the military victories. It is impossible to explain this last-act recovery—really discovery—of his power after two terms of failure as president, more failure at business, and his pathetic search for acclaim, except on the theory that the writing made him relive the war years that had touched him with moments of true greatness.

Sherman’s writing was a less heroic business and obviously more enjoyable, done in a period of three years when he was full of beans. He enjoyed the company of women as well as dancing and theater, amateur painting, and quoting Shakespeare. With the Memoirs he did not take the pains he might have in checking facts and called it in his preface to the first edition “merely his recollection of events, corrected by a reference to his own memoranda.” Shortly before publication he wrote his brother, Senator John Sherman, “I have carefully eliminated everything calculated to raise controversy.” Calculated or not, controversy was certainly raised. In a second edition in 1886 (the one used here) he undertook to correct factual errors (some fifty, the editor finds) but not to reconcile his own memory of events with that of others. “I am publishing my own memoirs, not theirs,” he declared somewhat testily.

Both of the generals give several chapters to the years of their youth before the Civil War. Both were descended from early-seventeenth-century New England settlers who moved west, the Shermans a cut or two above the Grants in social standing. Sherman, whose father was a judge on the Ohio Supreme Court, married the daughter of a member of President Taylor’s cabinet, and the marriage was attended by Daniel Webster, Henry Clay, President Taylor, “and all his cabinet.” Grant, whose father ran a tannery and a leather goods store, married Julia Dent of Missouri, the stumpy, wall-eyed daughter of a small slaveholding planter, and the most stabilizing element in U.S. Grant’s entire life.

These are memoirs, not autobiographies, and much of importance about these men is not found here. “Of omissions there are plenty,” as Sherman admits. On six crucial years in Grant’s life, between 1854 and 1860, almost nothing is to be found. Separated from Julia and his family by military duty in the far West, he became dangerously depressed, took to the bottle, resigned his commission as an army captain, and went from bad to worse. Back with Julia, he failed miserably at everything he tried, and as a final humiliation threw himself on the mercy of his father, who offered him a clerk’s job in Galina, Illinois.1 For all his candor, Sherman tells us little about his frightening and crippling spells of depression. It was a long and recurring affliction and some seizures were more acute than others. The one that overwhelmed him in the fall of 1861 with obsessions and irrational conduct was so severe that his army superiors sent him home for rest. There his suicidal inclinations induced his wife to write his brother, Senator John, about “that melancholy insanity to which your family is subject.”2

Advertisement

For the afflictions that beset Sherman and Grant, the war, all-out war, was to prove the most reliable therapy. Yet at the outset of their military careers, neither man gave promise of becoming a good or even a willing soldier, much less a genius of world fame. When Grant’s father told him he had secured an appointment to West Point for him, he replied, “But I won’t go.” He did go, but with “no intention then of remaining in the army.” He would finish West Point, but “afterward obtain a permanent position as professor in some respectable college,” a hope he was slow to abandon. “I do not walk military,” he discovered, and acquired “a distaste for military uniforms” which he never overcame. The way he wore them in photographs proves that, even after they bore the maximum number of stars. The sight of blood—in a Shiloh hospital, at a Mexican bull fight, even the sight of a medium-rare steak—was likely to sicken him. Charles Francis Adams described him after the Battle of the Wilderness as “a very ordinary looking man,” “a dumpy and slouchy little subaltern,” a rather “comical” figure, who “in walking leans forward and toddles.”

Sherman could “walk military,” and he cut a more impressive figure as a man, though he managed to look scruffy and disheveled in most of his photographs. He shared many of Grant’s aversions to military life in peacetime. “At the Academy,” he wrote,

I was not considered a good soldier…but remained a private throughout the whole four years. Then, as now, neatness in dress and form, with a strict conformity to the rules, were the qualifications required for office, and I suppose I was found not to excell in any of these.

He did well enough in his studies, but demerits for conduct reduced his standing. Grant ranked near the foot of his class in tactics. He was assigned duty in the war with Mexico, which he thoroughly detested as an unjust cause, but he fought in “all the engagements possible for any one man and in a regiment that lost more officers during the war than it ever had present at any one engagement.” This experience proved to be not only of military value to him during the Civil War, but in advancing him in rank when he returned to the army.

Sherman saw no combat duty in Mexico, but had army assignments in the South—in Florida, South Carolina, Louisiana, and Georgia—that were to prove of military value later. In Georgia, he writes, “by mere accident I was enabled to traverse on horseback the very ground where in after-years I had to conduct vast armies and fight great battles.” At the same time he formed an affection toward southerners and friendships among them that survived the war. After resigning his army commission in 1853 and undergoing some unfortunate business and banking misadventures out West, he returned to Louisiana in 1859 to become head of the new state military academy that later became Louisiana State University. He describes his farewell to the students when he resigned to go north on the eve of the war as quite emotional. Grant admired southerners for their boldness and courage.

Neither Sherman nor Grant professed any interest in slavery and emancipation as moral issues or any particular sympathy for slaves, though Sherman, when asked his opinions in Louisiana, said he favored a law against separating their families. But had the South stuck to the constitutional guarantee of property rights, he later declared, “I for one would have fought for the protection of the slave property as for any other kind of property.” He predicted that agitation of the slavery issue would lead to civil war. To his brother he wrote, “I would not if I could abolish or modify slavery.” And when he was planning to bring his wife to join him in Louisiana, he considered “buying a nigger” for the household, since they “won’t work unless they are owned.”

Grant had owned slaves, and worked them unsuccessfully on his farm. He made no secret of his own views on slavery as a national issue. “I never was an Abolitionest [sic], not even what could be called anti slavery,” he wrote a prominent politician, “but I try to judge farely [sic] & honestly.” That led him early in the war to the belief that “North & South could never live in peace with each other except as one nation, and that without Slavery.” The first president (and for Sherman the only one) whom both men voted for was the Democrat James Buchanan, the South’s favorite in 1856. Grant was generous to a fault in praising his white troops, not the others, and Sherman treated the swarms of slaves that followed his army as a nuisance or worse. He strongly opposed recruiting black troops on the ground that they were inferior and their use would offend white soldiers.

Advertisement

When war came both men applied for commissions as colonel in the army about the same time. Grant’s letter was lost or ignored, and he marked time for a while. Sherman was commissioned in time to take part in the defeat at Bull Run. But his military fame, like Grant’s, was to be made later in the western theater of war. Both men rose to their opportunity from the depths, Grant from years of humiliating failure and the reputation of a drunk, Sherman from a spell of raging depression, despair, and alcoholism after Bull Run which had him repeatedly described in the press as “insane” and “stark mad.” From these points of departure there was no direction left to take but up, and both men took it.

Grant went straight for the jugular, southward, captured Fort Henry on the Tennessee River on February 6, 1862, and went right on to Fort Donelson, which surrendered ten days later on terms of “unconditional and immediate surrender,” thus linking the terms of surrender with the initials of Grant’s name forever in the popular mind. On the way to Fort Donelson he received reinforcement and supplies from Sherman, now brigadier general, who joined forces under the command of Grant, now major general, to fight the terrible battle at Shiloh in April. It was their first meeting since an encounter years before on the streets of St. Louis, where Grant then peddled firewood for a living. Sherman defended Grant in public and private letters when he was criticized in the press for falling victim to a surprise attack and sustaining heavy casualties at Shiloh.

There were temporary setbacks and separations while each commander developed his own style and strategy of warfare. Long before the march through Georgia Sherman brought war home to civilians of all ages in Tennessee and Arkansas by burning towns, expelling scores of families from Memphis, and destroying all property, crops, and houses for fifteen miles along the Arkansas banks of the Mississippi. Meantime Grant was preparing another lunge southward, this time for the strategic city of Vicksburg on the Mississippi, and ordered Sherman to move on the objective with four divisions and about one hundred vessels, while Grant advanced southward by railroad. Grant was delayed and Sherman’s assault on Confederate defenses north of Vicksburg with 30,000 men was repulsed and failed. So did Grant’s effort to bypass Vicksburg fortifications by cutting a canal. The city finally surrendered under a siege on July 4, 1863, the day after the Union victory at Gettysburg in the East.

These events are recorded by the memoirists in ways as distinctive as the military styles they were developing. Grant writes in the informal, commonsensical, laconic manner that won him the loyalty and obedience of his troops. He is both personal and objective, never pretentious, rarely complaining, always careful in criticism, whether of his subordinates or his enemies, and generous with his praise. His modesty was habitual: “I had no idea, myself, of ever having any large command.” He could accept blame and confess error. He sometimes hastily brushes aside setbacks, but he could come forth with the confession that the horror of the fighting at Cold Harbor produced “no advantage whatever…to compensate for the heavy loss we sustained,” and he pronounced the blowing up of the Petersburg fortifications “a stupendous failure” that cost some four thousand men. One can understand what Alexander H. Stephens, vice-president of the Confederacy, meant when he said on first meeting Grant near the end of the war, “He is one of the most remarkable men I have ever met. He does not seem to be aware of his powers.”

Sherman was aware of his, all right, but he never let that get in the way of his candor, his logic, and his awareness of the limits of power and authority. His tremendous energy was flamboyant and explosive rather than contained, his speech full of profanity and expletive, his tastes and manners democratic, though he was outspokenly skeptical of democracy: “Vox populi, vox humbug,” he scoffed. He could combine headlong action with thoughtful reflection, ruthlessness with compassion, cool detachment with personal affection. He too knew how important it was “to gain the heart of his army,” but he went about it in his own way. A man then in his mid-forties, with the rank of major general, he pictures himself “creeping forward to the skirmish line” under fire; or again: “Being on foot myself, no man could complain, and we generally went at the double-quick,” sometimes through swamp, “where the water came above my hips.” He liked to throw in an occasional anecdote, like the one about an officer of Irish origins listening to surgeons debating whether to amputate his leg and intervening with the plea that it was an “imported” leg, and how the laugh spared him the amputation. Or the debate between two Confederates about whether to blow up a tunnel, the winning argument being, “Oh, hell! Don’t you know that old Sherman carries a duplicate tunnel along?”

Before the end of the war Grant was seeing Lincoln regularly and often. Given the President’s high regard for the general, we may assume he would have listened to any advice Grant had to offer on affairs of state, particularly in the South. If he ventured any, his Memoirs do not mention it. Grant had no aptitude for politics, as his presidency (also unmentioned in the Memoirs) amply demonstrates. “I did not want the presidency,” he wrote, but he ran for the office three times and was elected twice. Henry Adams, who had known a dozen presidents in the White House (besides having a couple in the family) “found Grant the most curious” and pronounced him “pre-intellectual, archaic,” a reversion to the cave-dweller stage of development. “The progress of evolution from President Washington to President Grant was alone evidence enough to upset Darwin,” in the opinion of Adams. The Grant administration was bad enough, to be sure, but Adams went on to say, “He had no right to exist. He should have been extinct for ages.” The Adams rhetoric occasionally got out of control.

Sherman shared Grant’s aversion to politics and politicians and was more successful in avoiding elective office, but he had many opinions on matters of politics and policy and was quite willing to share them. In September 1863, he wrote a long letter to Commander-in-Chief H.W. Halleck (obviously intended for the attention of higher authority) in which he analyzed class divisions in the South with regard to war and postwar Union policy. First there was “the ruling class,” that is, “large planters, owning land, slaves, and all kinds of personal property,” who were the key to the problem. Once they were persuaded by military means that their cause was hopeless, “I know we can manage this class.” It would be best “to allow the planters, with individual exceptions, gradually to recover their plantations, to hire any species of labor, and to adopt themselves to the new order of things.” As for “the smaller farmers, mechanics, merchants, and laborers,” who made up some “three-quarters of the whole,” they were “hardly worthy a thought; for they swerve to and fro according to events.”

Then there were the “Union men of the South,” for whom, he said, “I confess I have little respect…. They allowed a clamorous set of demagogues to muzzle and drive them as a pack of curs…. I account them as nothing in this great game of war.” Quite another matter were

the young bloods of the South: sons of planters…. War suits them, and the rascals are brave, fine riders, bold to rashness, and dangerous subjects in every sense. They care not a sou for niggers, land, or any thing. They hate Yankees per se, and don’t bother their brains about the past, present, or future…. This is a larger class than most men suppose, and they are the most dangerous set of men that this war has turned loose upon the world.

They had to be absolutely destroyed or converted to Union uses. Any thought of civil government for any part of rebeldom until total Union victory and for some time thereafter “would be simply ridiculous.” About his letter he was pleased to receive report that “Mr. Lincoln had read it carefully” and “more than once referred to it with marks of approval.” History provides little evidence that Lincoln followed the general’s advice.

Grant and Sherman fought the last year of the war in separate theaters, with Grant ordered east in command of all Union armies, and Sherman in the West. Each pursued his own strategy with deadly coordination, each a variation of a newly emerging total war. Grant’s has been characterized as a strategy of “annihilation,” based on the theory that this was a war for survival, not for “victory” in the usual sense. To defeat the brilliant Lee in a series of battles was not enough, for as long as Lee’s forces remained in the field it was the Confederacy that survived, not the Union. They had to be destroyed. With that purpose relentlessly in mind, Grant waged war in Virginia with a savagery and brutality unthinkable in the earlier years. The sickening list of casualties he sustained and those he inflicted at the battles of the Wilderness, Spotsylvania, Cold Harbor, and Petersburg earned him the name of butcher. His answer was that this was better than an endless stalemate, even though he admitted that there was no justification for the six thousand men lost in an hour at Cold Harbor. He continued to sit inconspicuously through the roaring blood-baths, whittling a stick, smoking a cigar, and enduring devastating headaches only rarely relieved by a binge.

While Grant continued to approach Richmond, slipping steadily around Lee’s right flank, Sherman moved southward from Chattanooga through Georgia toward Atlanta, also with flanking maneuvers, around a retreating General Joseph E. Johnston. Finding his supply line and railroad threatened by the Confederates, he saw the opportunity to apply his own theory of war to the fullest and wired Grant:

I would infinitely prefer to make a wreck of the road and of the country from Chattanooga to Atlanta, including the latter city; send back all my wounded and unserviceable men, and with my effective army move through Georgia, smashing things to the sea…. Instead of being on the defensive, I will be on the offensive. Instead of my guessing at what he means to do, he will have to guess at my plans. The difference in war would be fully twenty-five per cent. I can make Savannah, Charleston, or the mouth of the Chattahoochee (Appalachicola). Answer quick, as I know we will not have the telegraph long.

Grant approved after a delay and Sherman went ahead with his proposed plans after driving the Confederate forces into their Atlanta fortifications and pouring continuous artillery fire on the city. When the new Confederate commander, General John B. Hood, evacuated Atlanta, Sherman ordered the expulsion of all civilians and occupied the city solely for military uses. His supply lines cut as he anticipated, he destroyed railroads, factories, and parts of the city, left a force of sixty thousand men to face Hood, and with a force equal to those marched eastward filled with “an unusual feeling of exhilaration…of something to come, vague and undefined, still full of venture and intense interest.” His Memoirs powerfully convey that sense to the reader. Living richly off the land, his troops, moving forward ten miles a day, destroyed railroads, factories, government buildings, cotton gins, crops, livestock, and much private property, clearing a path of devastation fifty to sixty miles wide to Savannah. Then they turned northward and laid waste to the Carolinas with even greater fury.

Sherman’s exhilaration as he set forth on that march may have been, as Edmund Wilson suggests, “the strong throb of the lust to dominate and the ecstasy of its satisfaction.” That in part, perhaps, but it was also the excitement of an inspired theorist about to put into practice an idea that was to revolutionize the profession of warfare. The British military expert B.H. Liddell Hart supports this view. Believing Sherman to be the most outstanding of “a galaxy of brilliant tacticians” in the “first great war of industrial civilization,” Hart calls him “the first modern strategist,” with no rival or equal between the American Civil War and the Second World War. German masters of the Blitzkrieg as well as General Patton acknowledge indebtedness to Sherman. Put in its simplest terms by Hart, Sherman’s innovation was “to strike at the sources of the opponent’s armed power, instead of attacking its shield—the armed forces.”3 Once the economic and moral support was undermined, once the civilians were forced to see their cause was hopeless, the armed shield would collapse. “I was strongly inspired,” wrote Sherman,

that the movement on our part was a direct attack upon the rebel army and the rebel capital at Richmond, though a full thousand miles of hostile country intervened, and that, for better or worse, it would end the war.

Whether that did it, or whether it was Grant relentlessly beating his head against the “shield,” or both together, Richmond fell, and Lee retreated with his diminishing forces westward, Grant in pursuit. “Suffering very severely with a sick-headache” all night as he waited word from Lee about a meeting to discuss terms, Grant was “still suffering with the headache” the next morning, “but the instant I saw the contents of [Lee’s] note I was cured.” He then set forth for the meeting in the farmhouse at Appomattox Court House. That famous encounter, the two protagonists perfectly cast and attired for their respective roles, is arguably the most moving moment in American annals. It was undoubtedly Grant’s finest hour, and he did not spoil it with a hint of bravado or one false note. Nor could his narrative of the meeting in his Memoirs, in all its simplicity, have been improved. It is only fifteen pages long. It has to be read.

It was Grant, of course, who set the terms and Lee who gratefully accepted them, but it was Lee who set the tone of the meeting and Grant who willingly conformed. The one was in the mud-spattered uniform of a private with only the shoulder straps showing his rank; the other stood taller in full uniform and a handsome sword. The two of them managed to restore to history’s first total war of the industrial age a momentary measure of personal grace and humaneness that belonged to another age of warfare and another period of history. “Lee and I then separated as cordially as we met,” wrote Grant. His first order after that was to suppress a celebration in his army touched off by the news of the surrender. “I felt like anything rather than rejoicing,” he said.

Finally, a word about the editing of these volumes. Each of the memoirs, in addition to an index, contains a full year-by-year “chronology,” not only the years covered by the book but those of the author’s entire life. As editor of the Sherman volume, Charles Royster has provided notes. The McFeelys add not only notes but a rich selection of Grant’s letters, some 250 pages of them. Such services are usually granted more generous acknowledgment than is accorded the editors in this instance.

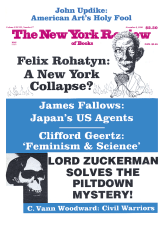

This Issue

November 8, 1990

-

1

William S. McFeely’s Grant: A Biography (Norton, 1981) deals with these and later phases of Grant’s alcoholism with candor and fairness. Some sensational episodes during the war are pictured by Sylvanus Cadwallader, Three Years With Grant (Knopf, 1955). ↩

-

2

B.H. Liddell Hart, Sherman: Soldier, Realist, American (Praeger, 1958), pp. 23, 36, 46, 66, 93; Edmund Wilson, Patriotic Gore: Studies in the Literature of the American Civil War (Oxford University Press, 1962), p. 181. ↩

-

3

Foreword by B.H. Liddell Hart in Memoirs of General William T. Sherman by Himself (Reprint of 1886 ed., Indiana University Press, 1957), pp. vi–xii. ↩