1.

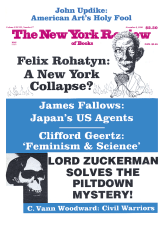

New York City is facing a social, political, and economic crisis far more serious than the fiscal crisis of the 1970s. This is reflected both in the life of the city itself and in the attitudes toward the city in Washington and in the rest of the country. Fifteen years ago President Ford gave a speech on New York which was accurately summarized by the Daily News as FORD TO CITY: DROP DEAD. In fact after the headline appeared President Ford did not do as well as the city did. Many of us believe that his remarks cost him the state’s electoral votes and the presidential election in 1976, whereas the city managed to make a recovery and went on to a decade of considerable prosperity.

A few weeks ago President Bush, in a speech to New York Republicans, said that “life in New York, especially in the city, is becoming more expensive, more difficult and more dangerous than ever before.” New York City, he went on, is a “city that lives in fear.” He spoke of “bad schools, dangerous streets, big deficits, open-air drug markets and muggings,” without mentioning that a decade of neglect of urban problems by the Reagan and Bush administrations helped to bring this situation about. But while his description generally was accurate, the way the city is perceived is even worse than the reality, not only in the United States, but also abroad.

The statements of the two presidents, and the reactions to them, suggest some of the main differences between the fiscal crisis of 1975 and the far deeper crisis that the city is now facing. In 1975, the New York press attacked Ford relentlessly for his antagonism to the city’s needs. The coalition of city businessmen and labor leaders who were then working effectively on the city’s financial problems lobbied furiously in Washington for the appropriations that Ford wanted to deny them; so did a political coalition of northeastern states led by New York. President Giscard d’Estaing of France and Chancellor Helmut Schmidt of West Germany personally urged President Ford to provide federal credits to the city.

Finally, although grudgingly, the president and the Congress decided that it was better to help New York City than to bury it; and this decision was, to a large extent, made easier by what New York was doing to help itself. New York State put its credit behind the city’s. New York’s labor leaders agreed to far-reaching concessions on such matters as salaries and hiring; New York’s banks, many of them with a significant part of their capital at stake, agreed to contribute to refinance the city’s debt; a new city administration, with the help of the Emergency Financial Control Board and the Municipal Assistance Corporation, brought the city back to financial equilibrium. The city both helped to bring about and benefited from the financial boom of the early Eighties. Despite the departure of a number of businesses during the Seventies, the mood of the city was decidedly upbeat. Many New Yorkers felt that they had waged, against very long odds, a political battle for the future of the city and that they had won.

The reaction to Bush’s recent statement, on the other hand, was muted. Apart from Senator Moynihan’s comment that only China and Albania deserved such scorn and some critical remarks by Congressman Charles Rangel, the statement was ignored by political leaders and the press. It was ignored not only because Bush’s words were much less threatening to the life of the city as Ford’s were, but also because the city today is vastly different from the city of 1975. There is no longer effective cooperation between business and labor. There is no strategic political alliance between the city and the state, which would deal with the city’s problems in Albany or in Washington. There is now a feeling of helplessness about the city’s long-term difficulties.

To make realistic comments about the city’s problems today can be risky. Anyone who does so is likely to be accused of “talking the city down.” Politicians regularly criticize the press for giving too much space to crime, homelessness, racism, and drugs, as if ignoring the truth about what is happening in the city would somehow make it go away. In fact, the attention given to violent crime in the press during the past several months has served to draw public attention to spreading patterns of danger and desperation which are leaving no section of the city untouched. Mayor Dinkins has now proposed an ambitious and wide-ranging “safe city, safe streets” program. Will this program be capable of recapturing the streets and the subways from criminals, and of getting legislative action to provide for stiffer and more intelligently administered criminal penalities? It deserves strong support, but it is too soon to hope that it will.

Advertisement

New York City, during the 1975 fiscal crisis, could still be described as a “gorgeous mosaic.” Mosaics are held together by some bonding material that keeps them from falling apart. During the 1970s there were, I believe, widely shared hopes that the city could provide opportunity for its citizens. Today, New York has become a city full of anger and violence in which ethnic groups are turned against other ethnic groups, races against other races, classes against other classes. The quality of life is the dominant economic, social, and political issue facing the city today. And whether for black or white, Hispanic or Asian, rich or poor, the daily experience of the city is becoming more and more unpleasant. That other cities in the US may be worse off, as many claim, is not really relevant. New York has to judge itself against its own past and its own standards. The many wonderful aspects of life in the city, its intellectual and cultural life, its energy and variety, are being buried by grinding pressures arising from civic failures—the streets and subways that are not safe; the public places that are not clean; the schools that are failing to educate; and the drugs that are more and more widely sold. I cannot imagine leaving the city myself, but many other people and a number of businesses are thinking of doing so.

These problems did not start under the Dinkins administration and they should not be laid at its feet. There is no shortage of plausible explanations for the city’s plight. These include the various failures of the federal government to support urban programs, to fight drugs, to fight crime, to provide assistance for housing, public transportation, and so on. Had federal urban programs remained at 1981 levels, New York City would receive an additional $2.4 billion of budget support for the fiscal year 1991. The reasons for the situation in the city also include the inability of the state to provide greater financial support for the city, especially for public education in the poorer school districts. But to change state and federal spending policies will require time and a drastic political realignment. In public life, there are no static conditions; things get better or they get worse. In New York City right now, they are getting worse. In order for things to get better, the city will have to make some fundamental, possibly radical, changes in the way it goes about its business.

Many misleading myths circulate in the city today, inhibiting efforts for reform and encouraging the acceptance of the unacceptable. One of the most pervasive is the myth that its only problem is the lack of means. The problems of the city are not only created by a lack of money. A city with a budget of $29 billion, a payroll of $15 billion, a municipal work force of over 300,000 people, and a capital program of $5 billion per year is not exactly without resources, even though the needs to be met are enormous. The last ten years have seen the work force of the city grow by more than 50,000 people; at the same time, labor contracts have become more generous in both compensation and benefits. And yet despite the significant increase in the size of the city’s work force and in the compensation of its members, the services delivered to New Yorkers have not improved and the quality of life in the city has steadily deteriorated. The time has come to question the city’s overall wage and personnel policy, which up now appeared to have three elements: continued increases in the number of employees; across-the-board increases in compensation, regardless of merit; little or no real increase in productivity. The labor negotiations of September and early October provided an opportunity for change; so far they have resulted only in confusion and a perplexed concern about the direction in which the city is going.

The city’s estimated budget deficit for 1991 of $1.3 billion was eliminated by raising almost $800 million in new taxes, by drawing on $300 million surplus funds and balances of the Municipal Assistance Corporation, and by various savings on expenditures. Measures of this kind cannot be repeated forever. It is already becoming clear, in view of the sharp deterioration in the city’s economy, that this year’s budget is sliding into deficit and that another large budget gap is to be expected next year, which could exceed $1.5 billion, without any increase in labor costs. Dealing with these future deficits will be the main challenge to the Dinkins administration.

The city must develop an overall economic and management philosophy in setting wage and employment policies. Failure to do so, in the present highly uncertain economic environment, will result in a large number of layoffs and cuts in services that will be damaging to both the city and its employees. To begin with, the increase of 1.5 percent in labor costs to the city that has been included in this year’s budget is more than the city can afford, and less than the unions are willing to settle for. The city could not find the $30 to $50 million required to hire one thousand additional policemen and had to finance these additions to the force by piecemeal cutbacks in everything from education to libraries. With the city’s economy in a recession, and the national economy entering one, there should be a freeze on wages until we have a clearer picture of the economic outlook and the city can negotiate with its unions a different approach to wages and hiring.

Advertisement

Nothing would be more destructive to the city’s economy, as well as to its workers, than labor settlements at salaries and benefits the city cannot afford—settlements that would have to be financed by further tax increases, which would drive more people and businesses away, and by widespread layoffs of city employees. The situation created by the tentative agreement reached between the city and the United Federation of Teachers (UFT) at the beginning of October proves this point. The settlement provides for a 5.8 percent increase, of which 1.5 percent is to come from the city’s budget, 2.5 percent from reduced city contributions to its pension funds, and the balance by the diversion of state aid funds to education. Two days after the settlement was announced, along with a proposal to add thousands of policemen to provide safety on the streets, the city administration, citing a sharp downturn in revenues caused by a weak economy, announced budgetary cutbacks which included layoffs for 15,000 city employees and a freeze on wages and hiring. We have not seen layoffs on this scale since the summer of 1975. The unions immediately expressed fierce opposition to the city’s announced plan.

The city comptroller, Elizabeth Holtzman, has estimated that if the terms of the settlement with the teachers were applied to all existing labor contracts, next year’s budget gap could reach $2.4 billion. Camouflaging the real costs of a settlement by the use of pension fund assets, as some now propose, is not a responsible solution. If, indeed, the city can prudently reduce its contribution to its pension funds the benefits of that reduction should be used to maintain city services (such as an enlarged police force) and not to benefit any one union. The city, after all, is the guarantor against any shortfall in the pension funds. What is clear, at this point, is that the city should set aside the new teachers’ contract and develop a comprehensive financial plan in consultation, as in 1975, with both the state and the municipal unions. Budget gaps of the magnitude now projected cannot be filled without unacceptable and permanent damage to the city and its entire social structure. Even if the city comptroller’s budget forecasts are on the pessimistic side, deficits approaching this magnitude would result in significantly more numerous layoffs than the 15,000 already proposed by the city and heavy additional new taxes on businesses and individuals. This would be a social and economic disaster. It would be far better to admit to a mistake over the teachers’ contract than to compound the city’s problems by extending it to the other unions for the sake of consistency. We will soon find out whether the city administration is willing and able to do so.

Clearly, the city now faces a fiscal crisis at least as serious as the one in 1975. While there is no imminent danger of bankruptcy now, since the city’s debt has been restructured over the years, the expected budget gaps are similar in relative size while the underlying problems are more serious. The state is not in a position to help the city as it did in 1975. AIDS and crack did not exist then; homelessness was not as widespread; crime seemed less of a problem; the educational system appeared more stable. Under these circumstances some of the approaches and the administrative structures which served the city well then should be brought into play now.

The principles behind the agreements reached in 1975 were straightforward. Sacrifice was to be shared as fairly as possible. There was a constructive dialogue between representatives of business and labor. The city and the state worked closely together, the Financial Control Board (FCB) concentrating on the city’s budgetary problems and the Municipal Assistance Corporation (MAC) on its borrowing problems. There is no current need for MAC to provide financing for the city since New York now has adequate access to financial markets. But the city, which has been put on a credit watch by Standard and Poor’s, must be careful to preserve its credit rating. The credit markets are more skittish today than they have been for years. However, the FCB, which consists of the governor, the mayor, the elected state and city comptrollers, and three private citizens, could be the appropriate vehicle for the city and the state to cooperate on a comprehensive, multiyear financial plan. Including as it does the city’s and the state’s highest elected officials, the FCB has a professional staff which could help in drawing up a plan that would be in effect for between two and four years.

As it did in 1975, the plan should defer all wage increases that have been or will be negotiated under collective bargaining agreements for the period of the plan; in exchange, the city should avoid layoffs, except as a last resort, as long as a hiring freeze and a program of attrition can produce an annual reduction of 5 to 6 percent in the city’s work force (amounting to a reduction of fifteen to eighteen thousand employees each year for an annual savings of about $500–600 million). The attrition program would exclude the police department and teachers; an appropriate package of new taxes, state assistance, plus such reduction in city pension fund contributions as may be deemed actuarily prudent, would close the remaining gap in the budget.

A plan along these lines could reflect the “Social Contract” of 1975 between the city and the state and between business and labor. It worked then and it should be tried now. As a result of the national recession, we are also going to see drastic cutbacks in New York’s private economy. Reduced expenditures in the public sector are inevitable but they should be as gradual as possible. Savings through attrition, whenever possible, are preferable to other ways of cutting labor costs such as extensive layoffs. An approach combining deferral of wage increases with attrition would minimize the shocks to the city’s social structure and to the economy.

Such a program puts a great premium on management. It also requires a fresh assessment of the city’s priorities. A recent report by a respected private group, the Citizen’s Budget Commission, made some useful suggestions when it recommended that the city should establish priorities among the different categories of city workers, and allocate its resources accordingly.

Thus, if crime control and public safety are to be the city’s first priority, more policemen should be recruited, trained, and hired, and the funds to pay them taken away, at least in part, from less important activities. But this can be done only as part of a comprehensive plan for realistically adjusting needs to resources. When the mayor recently announced that half of his new $1.8 billion anticrime program would be financed by a new payroll tax, the tax was quickly opposed by the Republican majority leader of the New York State Senate, and the plan may soon become obsolete. Proposals to raise taxes must be part of a plausible fiscal program that has yet to be formulated.

2.

Public education deserves equally urgent attention. Since the city needs to protect its teachers from attrition or layoffs, and to maintain what vitality is left in our public schools, the new chancellor, Joseph Fernandez, should be urged to reduce as drastically as possible the heavily overstaffed education bureaucracy at 110 Livingston Street in Brooklyn and the budgets of the local school boards, which seldom do anything to improve education. I have no doubt that deeper cuts can be made in the school bureaucracy without in any way reducing the quality of education. To the extent that such reductions are not sufficient, other less important functions of city government should be cut back to help pay the teachers. Deciding which city functions should have more or less financing, and how much, within a policy of retrenching by attrition is a difficult challenge for management. But that, after all, is what managers are paid to do.

Even with wage deferrals and personnel cutbacks, some additional taxes will be necessary. They will pay for police as part of the mayor’s “safe streets” program, to protect teachers from attrition, and for critically needed programs of capital improvements that will nevertheless be cut back. But we have just had a $800 million tax increase and, in New York today, virtually all human activities are taxed to the hilt, while the quality of life is not acceptable.

Before the city adds to its already heavy tax burden New Yorkers should be presented by city and state leaders with a long-term plan of the kind already mentioned for the city’s economy and for improving its services, including both revenue measures and plans for cutting expenditures that will enable New York to keep its existing business base and provide for its needy citizens. Tax increases will have to be part of any balanced program; they will have to be fair and they should be moderate. The city’s strategy must be to maintain New York as the financial capital of the world and to aspire to become the tourist capital of the world as well. The paramount consideration must be to create jobs to support the city’s needs.

The backbone of the city’s economy consists of industries that provide services: banking, brokerage, accounting, and other financial services, communications, press, publishing, and entertainment, to name only a few. In the garment business and other small industries, design, marketing, sales, administration, and promotion are as important as manufacturing. Modern technology makes it easy for many of these industries to move not only to New Jersey, but to Denver, London, or Singapore. These industries, from the clerical level upward, require skilled, educated high-school and college graduates, and they will pay them well. But if adequately trained young people are not available locally, as increasingly they are not, the industries will move elsewhere.

Again, money is not the only problem. Certainly the city should get a fairer share of the state’s public school allocation formula. But we already spend $6.5 billion a year, or $6,500 per child, for a system that produces truly horrendous results. The school dropout rate is about 40 percent. We do not know the real level of literacy and other skills of those who get high school diplomas; but there is much evidence to suggest that many of them are deeply ignorant and have trouble reading. Nor do we know how many young people finally graduate from a college or university, or how many drop out before doing so, or how much those who graduate have learned. We do know, however, that New York City banks or telecommunications companies have to interview thousands of applicants to fill a few hundred clerical jobs. That simple fact suggests one of the most ominous threats facing the city today.

The city now has in Joseph Fernandez an excellent school chancellor who has been trying for the last two years to tame a sullen and intransigent bureaucracy and fundamentally change the system. Drawing on his experience in Miami, he is trying to introduce a “school-based management system” under which, in each school, a working group including the principal, teachers, and parents would take responsibility for the school’s performance, from its curriculum to its budget.

But one excellent man, no matter how energetic, needs a great deal of help and time if he is to make and keep such changes in the system, and Mr. Fernandez may have neither sufficient time nor support. It took two years to get rid of the Board of Examiners, a largely useless group that made the appointment of competent teachers an unnecessarily cumbersome process. It imposes on prospective teachers and administrators a bureaucratic and delay-ridden exam system, which duplicates the state’s certification procedures. It took two years to start phasing out the absurd practice of giving a principal tenure to stay at a particular school; it took two years to create a separate agency for school construction and to provide for the schools an exemption from the Wicks law requiring individual and separate contractors for plumbing, electricity, carpentry, and every other construction operation, which adds 30 to 40 percent to normal construction costs, as well as years of delay.

How long will it take for the chancellor to establish control over the expensive but often useless local school boards? These are little more than sources of political patronage and corruption, costing millions of dollars without making any real contribution to the education of children. How long will Fernandez have to fight in court to obtain the veto he should have over the appointment of district superintendents, who now are appointed by the local school boards, often on the condition that they cooperate in hiring people who owe their jobs to political patronage? How long will it take to recapture the school buildings from the grip of the custodians union, which controls the use of the buildings and demands exorbitant compensation to keep them open during evenings and vacations, as well as often engaging in the most blatant kind of nepotism?

The Board of Education consists of seven members. Two are appointed by the mayor and one each by the five borough presidents. The board is thus an independent and unaccountable body, dominated by the political interests of various appointed officials. Charged with one of the critical functions of city government, it is not responsible to anyone. Will it ever be accountable to the mayor or to any public official for that matter? The answer to these and many other similar questions, I fear is now clear: too long or never.

We all know that many of New York’s public school children face enormous difficulties. Many of them come from families that do not speak English or have only a young, uneducated mother to look after them. They need to have people intervene early in their lives to provide them with tutoring and counselling and reading materials; they should be able to attend evening and summer sessions in the schools, and most of them cannot; their parents often need educational assistance as much as they do, and have no way to get it. Whoever mentions such needs will usually be told that they are grave but that additional money will be needed to meet them. It may, however, be time to concede that the existing educational structure itself is likely to fail and that additional funds by themselves will not make much difference. A drastic reorganization of our public school system may well be our only option.

In Minnesota, in Wisconsin, and in Oregon, plans to make the schools accountable by giving parents a real choice of schools for their children are being tried or discussed. Some of these plans include state funding to allow public school children to switch to private or parochial schools. These programs may not, in every detail, be appropriate for New York’s complexities. However, I believe that we should try to devise a system that would allow parents and children to choose the schools they want, including new and existing private schools, while maintaining some degree of state supervision and control so as to insure that the schools available will meet educational standards and that students who are poor and have difficulty learning will be protected.

Defenders of the public school system claim that the high school students now have a choice of courses and that gifted students may attend a few special schools such as the Bronx High School of Science, while some districts have offered a limited choice of schools to children in the lower grades. But this choice is clearly inadequate. Wisconsin and Minnesota are trying systems that provide state and city funding to new schools, including private schools, for every student enrolled. We should be making a similar effort in New York. The planners of the Wisconsin and Minnesota systems found that there were many advantages in giving funds to new schools rather than giving vouchers to parents, as some have proposed, because a system of direct subsidy gives the state greater control over both funding and the standards to be set. If we followed the Wisconsin and Minnesota models, many schools would be publicly financed, while the people who set them up could create distinctive settings for education by hiring their own teachers, designing their own curriculums, and putting in practice their own methods.

A portion of the $6,500 the city and state now pay annually for each student enrolled in the public school system, say $3,000 for each enrolled student, could go to the private school of the parents’ choice, once the school had been accredited; those funds would be diverted from the present school districts. Such a system would be similar in some respects to the school-based management program proposed by Chancellor Fernandez. But it would add the element of accountability: schools that could not attract enough students would cease to exist. Parents who found that their children were not learning and were not able to pass state administered tests in one school could turn to another.

Such a system, which might be carried out along the lines recently recommended by the Brookings Institution,* would present a new challenge to the existing public schools, and it might ultimately eliminate the need for much of the bureaucracy at 110 Livingston Street. It would also encourage the use of modern technology in schools, since many of the private schools would be likely to encourage use of computers, video, VCRs, and other technology, which are now in inexcusably scarce supply in public school classrooms. The city and the state should provide parents with the information to make educated choices among different schools; they should also provide transportation for students, and many other important services. The idea that inner-city parents cannot make intelligent choices on behalf of their children is absurd: much evidence suggests that, given the necessary information and opportunity, they will become involved in making decisions that will affect their children’s lives and that the choices they make will on the whole be as reasonable as those parents who have more resources.

In my view, the obstacles to radical reform of the public school system are so formidable that an alternative system allowing parents and children to choose the school they want should be pursued vigorously in Albany as well as in New York. I do not minimize the problems of organizing new schools, of giving subsidies to existing private schools, and of specifying the standards that all the independent schools and teachers receiving funds would have to meet. Much planning would have to be done before such a system was put into effect. Even then some of the schools may well be unsatisfactory, some parents will be disappointed, and some students may move too quickly from one school to another. Before being made available throughout the city, moreover, the system should first be tried on an experimental basis, say in one new school in each of the city’s thirty-two school districts. But if such a system is adopted at least parents and children will have open to them choices among schools which will be trying to attract them and which will have strong incentives to show that the children who attend them are learning. A new system, at almost any price, is preferable to what we have today.

New York City in my view is facing a choice between two possible futures. In one of them, there would be continuing deterioration in the quality of life, increasing racial and social tensions, a badly educated population less and less able to do modern work, and the flight of businesses and middle-class families that are financially able to move. The other future, in which New York could become the most attractive and exciting city in the world during the next century, is not difficult to visualize for those of us who love the city for its diversity and openness to the new. But finding a way to bring about this future is perhaps the greatest challenge the city has faced in its history.

—October 11, 1990

This Issue

November 8, 1990

-

*

See John E. Chubb and Terry M. Moe, What Price Democracy? Politics, Markets, and America’s Schools (Brookings Institution, 1990).

↩