Most Americans will agree that this country has classes. Remarks about the poor and the homeless make that clear, as do ruminations on the rich and famous. But whether we feel we have a class system, let alone a class struggle, is another matter. So while admitting that classes—of some kind—exist, most of us do not want to push the notion too far. Better, for example, to speak of “blue collar” employees than to worry about whether we have a “working class.”

This reluctance disturbs Benjamin DeMott, a professor of English at Amherst College, who has chosen to subtitle his book Why Americans Can’t Think Straight About Class. In his view, class lines comprise a central reality of American life, and he asks, Why doesn’t the public face up to this fact? DeMott’s answer is that powerful forces, particularly the press and television and movies, have duped the public into swallowing the “distortions and lies” which maintain “the myth of classlessness.”

Most of The Imperial Middle is given over to describing “the rationalizations that help to suppress consciousness of social differences.” Marx called these illusions “false consciousness,” and much of DeMott’s analysis has a Marxian ring. Thus he posits that “the substance of class in contemporary America concerns differences in people’s actual physical, mental, [and] imaginative activity as workers.” He makes clear, for example, that class is not about purchasing preferences, such as wine versus beer, or what pictures you hang on your walls, but about the jobs people hold.

Virtually all of the data in The Imperial Middle comes from DeMott’s monitoring of the press and television and the movies. Along with reading and clipping newspapers, he has been a regular watcher of The Cosby Show, Cheers, and Cagney and Lacey, as well as Johnny Carson and David Letterman. Cartoonists like Jules Feiffer and William Hamilton are cited, as are movies ranging from Raging Bull and Pretty in Pink to Terms of Endearment and Working Girl. Real people—Gary Gilmore, for example, and Mary Beth Whitehead—are seen largely as artifacts created by the publicity given them. So the book is based mainly on homework. There are few references to sociological studies, which is no great loss, and none to interchanges DeMott may have had with members of the public.

The Imperial Middle never really names the main classes of American society. If bourgeoisie and proletariat no longer apply, it would nice to know why. (After all, those terms merely mean owners and workers.) DeMott argues his case largely from examples. He cites a Boston newspaper story which reported that the Copley Plaza told its maids they could no longer use mops: henceforward, they must scrub bathroom floors on their hands and knees. Their union filed a grievance, and the mayor canceled a large party that had been scheduled for the hotel. A management spokesman didn’t see what the fuss was all about: “A maid is a maid and this is just what she has to do.”

What is the class message here? DeMott seems to be saying that the maids, who represent one class, must do painful and unpleasant work so that the hotel’s guests, another class, will have sparkling bathrooms. If the maids could use mops, the work would still be menial. It is certainly true that hotels like the Copley Plaza depend on low-wage labor. This is also why most of us can buy oranges and apples at affordable prices. If maids and migrant laborers were paid considerably more, would this cease to be a class issue? Perhaps; but then the question becomes how the distribution of income might be changed, certainly an important issue. However, DeMott never explicitly says that the problem is that some people are receiving too large a share of the income pie.

Similar questions arise with the case of William and Betsy Stern, the New Jersey professional couple who hired Mary Beth Whitehead to carry a child for them. The Sterns could afford to spend $10,000 for that service. Mrs. Whitehead’s husband was a truck driver, and they were having a hard time making ends meet. So she sold the use of her body. If the Sterns and the Whiteheads had similar salaries, this sort of transaction would have been unlikely. But even if all families had equal incomes, we might still have surrogate motherhood, and we would then have to interpret the question of exploitation in other ways.

Of course, classes have social and cultural components, but power and privilege come mainly from money. An understanding of how it is distributed must underpin any class analysis. Much of the information we need appears in an annual income survey conducted by the Census Bureau. Its most recent report, covering 1989, found that the nation’s 93.3 million households had an aggregate income of $3.4 trillion. The report goes on to show how this sum was shared among 66.1 million families, plus 27.2 million people who live alone or with companions. The Census uses twenty income tiers (e.g., $15,000 to $20,000, $85,000 to $90,000) with a top bracket of $100,000 and over. Twenty-one categories are too many; so some compression will be necessary if we want a clearer image of classes within the income structure.

Advertisement

However, with statistics as with most other things, ideology tends to intervene. Table A (see page 45) suggests three pictures that could be drawn from the census figures.

The first supports what DeMott finds a delusion: that most Americans cluster in a broad middle stratum. That can be shown, but only by extending membership in the middle class to households with $20,000 incomes. In fact, many people in that range do see themselves as middle class. This is especially the case in regions with lower living costs, and it includes a great many retired people. False consciousness?

DeMott would prefer the figure in the center. It could be argued that in today’s economy, it takes at least $40,000 to live in a reasonably comfortable style, and only a third of the nation reaches that level. Of course, not all those below it are poor. Those in the bottom two thirds range from people in dire poverty to families struggling but doing decently on $35,000 a year. We also know that household income has barely budged during the last twenty years. Between 1969 and 1989, the median in constant dollars only moved from $28,344 to $28,906. In fact, this could be counted as a decline, since more households now need two earners to reach the latter sum.

However, The Imperial Middle is less concerned with who earns how much than with opportunity to get ahead. DeMott believes that most of those born into the bottom tier are doomed to stay there: social mobility is an illusion, or so uncommon as to hold out little hope. Even if the maids at the Copley Plaza enroll in evening classes and try to improve their diction, they will not fool anyone. In DeMott’s view, class in America is virtually European: your accent and demeanor will end up betraying you.

In fact, we have no reliable evidence on how many Americans move how far within their own lifetimes. Studies that compare individuals with their parents have limits, since social conditions change from generation to generation. Until recently, we expected most people to do better than their parents, since almost everyone in the society was riding on an upward escalator.1 Still, we have a few facts. The first is that millions of young people from working-class homes attend public universities and lesser-known private colleges. They are generally the first in their families to go on to higher education, itself an index of social mobility. The most recent figures from the US Department of Education, for 1987, show that public institutions of higher learning had 3,295,406 full-time students enrolled in undergraduate programs, and that at the end of the academic year 659,250 of the seniors received bachelors’ degrees. (The comparable figures for private colleges were 1,459,911 and 332,099.) Upward of 40 percent of these students come from families with incomes under $35,000. So not the least function of these schools is to allow young people to leave working-class families to embark on ascending careers. (At New York’s Queens College, where I teach, very few alumni remain in the borough.)

Undoubtedly, DeMott has strolled by the huge University of Massachusetts campus, which cannot be more than a mile from his Amherst office. Of course, not all of the 27,918 students there will reach the $40,000 level. But then not all of the 1,592 undergraduates at Amherst College will have stratospheric careers, either. Some may even find themselves being passed by University of Massachusetts alumni so far as incomes are concerned. One reason is that where you go to college counts less and less. The head of one of New York’s five biggest banks graduated from Princeton, which is what we might expect. But the other four attended Washington and Jefferson, NYU, Villanova, and a local technical college.

Nor is this situation atypical. Table B gives the educational backgrounds of the men who head a sampling of the country’s one thousand largest corporations.2

As can be seen, not one went to an Ivy League school, although Stanford and Amherst make the list. Well over half attended public colleges, and even those from private schools tended to have vocational majors like engineering and business. While corporate careers are not necessarily typical, they offer evidence that upward mobility has not declined in comparison with the past. If anything, downward mobility has been increasing. Think of all those Princeton graduates who won’t be heading banks.

Advertisement

But mobility is only part of the picture. In recent years, the real economic expansion has been at the very top, with the number and proportion of high-income Americans growing as never before. Here we must rely on the Internal Revenue Service for information, since Census categories stop at $100,000. The IRS figures are collated from tax returns, most of which come from couples or heads of households. As Table C (see below) shows, between 1968 and 1988 returns declaring adjusted gross incomes of $1 million or more increased from 1,122 to 65,303.

Indeed, in a two-year period, 1985 to 1987, the number doubled; and in a single year, 1987 to 1988, the growth was almost that great. Nor do these figures tell the entire story, since they include only declared income since certain sums may be subtracted.3

As it happens, few of the million-dollar returns come from corporate heads. Of the executives cited in Table B, only five had salaries and bonuses exceeding $1 million; the median figure for the group was $575,000. Needless to say, stock options and deferred compensation and golden parachutes can be part of the package; but they won’t appear on this year’s 1040. Nor are many athletes and entertainers up at that level. The real beneficiaries of income inflation have been in fields like medicine and law, as well as finance and real estate, along with men and women who own not-so-small firms of their own.

But the most striking finding is how those with high incomes have been growing as a proportion of the total taxpaying population. As Table C also indicates, between 1968 and 1988 returns declaring incomes in excess of one million rose from 51 to 595 per million taxpayers, almost a twelvefold increase. Among the less rich, between $100,000 and $500,000, there was a smaller but still substantial increase. (These figures have all been adjusted to take account of inflation. After all, a million dollars doesn’t buy what it once did.)

How has this been allowed to happen? After all, productivity in the economy has not exactly been improving. The stagnation of household incomes clearly reflects that. But since we have so many more doctors and lawyers and financial experts, one might think that competition would drive salaries down. In a similar vein, leaner-and-meaner companies tell us they are avidly cutting costs. Yet there seems to be a gentlemanly agreement to spare those at the top, even during recessionary interludes. Corporations do not cavil at the bills their lawyers submit, while brokers buy benefit plans that pay whatever their physicians ask. While few faculty salaries break the $100,000 barrier, the incomes of full professors rise as their teaching loads decline. And when colleges and law firms have to cut costs, they lay off lower-paid people rather than reduce the incomes of professors and partners.

But back to class. Income disparities are an obvious fact of American life, and the gaps have been growing. Cheap labor is also a reality, especially with so many aliens eager for work. Where mobility is concerned, the origins of corporate chairmen do not tell us how many of their high school classmates are parking-lot attendants. And privilege certainly persists. An Ivy League applicant can still count on preferment from professional schools.

Does all this add up to classes? I am not so sure. The structure and culture of American society can be explained by privilege and inequality, even exploitation; but not necessarily by a system of classes. There is too much movement, too many crosscutting factors like race and region and moral posturing. And, yes, a lot of self-induced false consciousness about where we would like to think we stand.

And this is the way it was supposed to be. James Madison, writing in The Federalist, expressed the concern of his fellow founders lest “those who are without property” coalesce into a class-conscious majority. To avert this eventuality, he wrote, “the society itself will be broken into so many parts, interests, and classes of citizens, that the rights of the minority will be in little danger from interested combinations of the majority.” This was not simply a prediction. All the forces DeMott mentions would be mobilized to divert attention from what Madison quite candidly called “the various and unequal distribution of property.”

Not every society in every phase of history is so constructed as to have simple class divisions. That is why, to the right on Table A, I created a third figure, which looks rather like a Doric column. The bottom quarter of the households having incomes under $15,000 are offset by about the same number at over $50,000, with the rest of the population in three tiers in between. Does this reflect the social reality or the pictures in people’s minds? The answer is both. That was the Madisonian prescription, and it has proved remarkably durable.

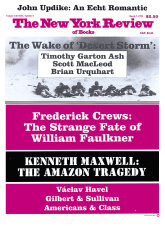

This Issue

March 7, 1991

-

1

See my “Cutting Classes,” The New York Review, March 4, 1976; and “Creating American Equality,” The New York Review, March 20, 1980.

↩ -

2

“The Corporate Elite,” Business Week, October 19, 1990. As is apparent, the sample below consists of the companies whose names begin with the letter L. Random checking found their chairmen to be a sufficiently representative group.

↩ -

3

Internal Revenue Service, Statistics of Income Bulletin, Fall 1990.

↩