Years ago I found myself in Indonesia, in Jakarta, which was once called Batavia, sitting at a table in a restaurant in the heart of the Chinese quarter of Glodok—near Kota, to anyone who knows this city, immense in extent, where the long streets change their names every two or three blocks, causing the visitor to go mad. I was reflecting on the menu, undecided between serpent soup, roast monkey, or a simple stuffed dog with hot pepper.

A young woman sitting at the next table with some other people was showing off two beautiful feet, at once thin and soft, brown on top and pink underneath, on which no shoe had left the slightest mark. In Indonesia feet are considered the most fascinating part of the female body, and everyone knows what small female feet mean to the Japanese; it is also known that in Vienna, around 1910, the tram stops were always crowded with groups of gentlemen waiting to admire the small feet of pretty women poking out from under their skirts for an instant as they boarded the car.

I myself have always had a weakness for women’s feet, and I hate people who tell jokes in which feet are associated with the odor of certain cheeses, like appenzeller, camembert, gorgonzola. For these same people, armpits can smell only of goats; and the behind… “It,” a sommelier would say, “has an intoxicating bouquet of roses and Parma violets….” I would add that “it,” because of its form—rounder than any solid of revolution or any circle traced by a compass—and because of its inscrutable mixture of the human and the divine, can be considered one of the most convincing proofs of the existence of God, certainly more convincing than the ontological argument of Saint Anselm.

Gorgonzola, that exquisite cheese whose moderate price has preserved its popularity, was born by chance in Lombardy, in the ancient city of Gorgonzola, which boasts among its most illustrious sons the printer Gorgonzola and the plumber Pietro Carminati Brambilla, called il Gorgonzola. Another illustrious son, the Marchese Busca, whose mansion is reflected in the calm waters of the Martesana canal, every year sent his friend Gioacchino Rossini some gorgonzola cheese, just as the celebrated pork butcher of Modena, Giuseppe Bellentani, sent Rossini salami and ravioli made especially for him. This predilection of Rossini’s is a distinction that our cheese doesn’t have to share with any other. Let’s not forget that the Maestro, a friend of the illustrious chef Marie Antoine Carême, has linked his name to at least five famous dishes: Tournedos Rossini, Cannelloni alla Rossini, Saddle of Veal Rossini, Suprême de Pintade Rossini, Friand of Chicken Rossini.

The train travels silently toward Gorgonzola through a green plain divided geometrically by canals full of clear water, with granite locks. Rows of enormous poplars with dancing leaves (Populus tremula) lead to villas and farmhouses of splendid design, all destined to be covered in a few years with cement. And then the day will come when there will be a lack of good arable land, and all that cement will have to be removed, at enormous expense, in order that the earth underneath may be found again: in order to eat, to survive. As the train passes, large herds of cows with clean, fragrant coats look straight into my eyes, without ceasing to chew their cud, as is their habit. Probably they are thinking the same things. To Liszt, who had come to visit him, the old Rossini said he had composed some rather tasty little piano pieces, and had titled them Fresh Butter, Lentils, Peas, Macaroni….

The interior monologue was born on a train. Joyce, more than inventing it, used it perhaps excessively. It seems to me that Joyce took a route opposite to that of a normal writer: he began with a classic (Dubliners), continued (Portrait of the Artist, Ulysses) with writings that became more and more complicated, and ended with a novel (Finnegans Wake) that is untranslatable and practically unreadable. Even if it’s true that defects are an integral part of perfection, I would like to try eliminating part of Ulysses—pages that are more or less incomprehensible, plays on words, on style, on punctuation, things still taken up, unfortunately, by the last Joyceans—and see what happens.

One of the first stations is Crescenzago. In Crescenzago there was a little restaurant with a beautiful young waitress…. So, even if you discard a few pages…. Many of Joyce’s admirers might have had the same thought, but…

To hell with serpents, monkeys, and dogs. In Jakarta I decided to order the dish they served to the beautiful Indonesian woman, and when they brought her some spring rolls, I—instead of writing the order on the appropriate pad, which is on every table—simply pointed out the dish to the waiter. Of course, to point I used my thumb and not my index finger, a gesture that is considered a serious offense there, and I used my right hand because the left is considered dirty, being used for post-defecatory ablutions: toilet paper is unknown in their toilets. I thought once of the embarrassing situations in which a beautiful left-handed girl might find herself; but surely I was mistaken, because tradition is always stronger than anything.

Advertisement

Meanwhile, various tour buses had stopped in front of the restaurant, and a crowd of hot tourists had invaded the place. An infinity of feet—deformed by shoes, and calluses of every sort, and twisted nails painted in lively colors to attract attention to their deformity (feet that irresistibly evoked the most vulgar jokes)—and dozens of buttocks that could testify only to the existence of the devil noisily found seats at the tables. The proprietor, one of the seven million Chinese with the name Chang, turned up the volume of the speakers in honor of the guests. Besides the eternal “The Orient is Red,” the most recent successful songs were being transmitted from Peking: “Recover the losses caused by the Four,” and “Govern the state centering the work on the class struggle.”

At the tourist office in Gorgonzola I take a leaflet with a plan for a tour of the city: photographic safari in the public park, which is inhabited by dwarf goats, hens, cockerels, pigeons, pheasants, swans, guinea pigs, ponies, donkeys…. On the way out, a stop at the ancient bakery on the Martesana canal and consumption on the spot of a fresh, ring-shaped loaf of French bread. Visit to the Palazzo Busca, formerly Serbelloni. Stop before the oil portrait of the Marchese Busca, the friend of Rossini. After the ancient bakery, visit to the terra-cotta kitchenware workshops, with shopping; visit to a cheese factory (as in London one might visit a brewery), with, at the end, a taste of gorgonzola accompanied by a little glass of sweet wine, offered by the firm as an apéritif; finally, lunch at the ancient inn where Renzo, the humble hero of Manzoni’s The Betrothed, fleeing Milan, stopped for dinner, and where the seat he occupied (nearest the entrance, “the place for the bashful,” says Manzoni) is marked by a plaque on the wall—just like the place reserved for Curnonsky in so many restaurants in Paris and the rest of France, where the celebrated prince of gastronomes could sit and eat, free, whatever he wanted.

After lunch, there remain two final monuments to photograph: the chapel in the middle of the Piazza della Chiesa dedicated to Saints Sebastian and Rocco, which was erected by Saint Carlo Borromeo during the plague of 1577; and, behind the church, the beautiful ancient bell tower, at the top of which Bishop Ottone Visconti hid, after losing the Battle of Gorgonzola (1278), and thus saved himself.

It is true that Curnonsky could sit and eat whatever he wanted free, but it must be said that in his last years, just when these plaques became so widespread, he was constrained to live on milk alone.

Normally Curnonsky would have a good meal at midday, and at night, for dinner, a hard-boiled egg. His name was Maurice Edmond Sailland and by his friends he was called Cur, or Curne. From his youth he had had literary ambitions, while his father wanted to start him in trade. Why, the young Maurice asked himself, should I not write? Why not? Cur non (in Latin)? This was the modest origin of his curious pen name, completed with a Russian ending, in homage to the fashion of those days, which originated with the czar’s visit to Paris. After working as a ghost writer for Willy, Colette’s first husband, he turned finally to gastronomy, with what success everyone knows. He died at eighty-three, when he fell off a balcony; and perhaps, while he was flying down toward the pavement of the courtyard, he was thinking, for the last time, Why not?

Gorgonzola was invented by chance in the last century by Signor Vergani, and in the Piazza della Chiesa there is no monument representing him in the act of making the fortunate mistake in his work. This unintentional birth has nothing embarrassing about it; rather, it unites gorgonzola with other classic delights of gastronomy, such as, to give a single example, Chicken Marengo, which was improvised, with the means at hand on the battlefield, by Napoleon’s Swiss chef: a chicken destined (perhaps) to live longer than the memory of the battle itself; and—destiny is strange—created for a man who, in addition to the many faults of which Madame de Staël accuses him, had the unpardonable one of considering time spent at the table time lost.

Advertisement

Gorgonzola has established (it seems) a twinship with Stilton, the English city that gives its name to this cheese with blue mold which is quite similar to gorgonzola but made of sheep’s milk, and is served with a piece of crusty bread and a glass of Port. Today the production of stilton is threatened by an enormous coal bed that has been discovered just beneath the land where the cheese is produced. The land of Gorgonzola doesn’t have coal beds, but, in any case, they would not be a threat, because gorgonzola—and here is the most startling information—is no longer made in Gorgonzola but in Novara, in Piedmont.

Other corrections to the tourist guide:

The Palazzo Busca: it is closed to the public.

The terra-cotta workshops: they don’t exist any longer.

The Manzonian inn: where it was there is today a furniture store.

The chapel of San Carlo: it stood until the end of the eighteenth century, then nothing more is known of it.

The bell tower: it was demolished a century and a half ago.

What is Gorgonzola today, without gorgonzola, without the ancient bell tower, without the Manzonian inn, without the chapel of San Carlo Borromeo, without the terra-cotta workshops, without the monument to Signor Vergani?

Is it nothing? Is it just one of those places where everything there was to see has been destroyed or taken away? Maybe so. And yet—I think, on the train returning to Milan, and assailed again by the temptation to interior monologue—it is nevertheless worth the trouble to go to Gorgonzola, even if only for the animals in the park, for stopping at Crescenzago, for the nearly absolute absence of tourists, for the taste, on the still and silent banks of the Martesana, of the fresh French ring bread, which comes out of the oven at eleven, it seems to me…. Men and women could be divided into two categories: those who can wear a watch on their wrist, and those who cannot, because the watch hangs crooked, with the back of the face hitting the bone…. Yes, it’s worthwhile to go to Gorgonzola even simply to stop at Crescenzago. The beautiful girl of Crescenzago had the whitest skin, lightly rosy on her cheeks, whose fragrance was the sum of all the natural perfumes emanating from a lovely female body, among them, besides the already mentioned scent of roses and Parma violets, the scent of vanilla cake, of the bosom (except for the bosom of Joan of Aragon, the Queen of Castile, who smelled of ripe peaches), the scent of Paradise, of the mouth, and so on….

Perhaps someone may wish to know something more. How she looked: blonde or brunette, the eyes, the mouth; tall, medium, short, plump; hands, feet… But physical descriptions, good for passports, are useless in a narrative work. Better, then, to point to some particular more indirect: she had a childish smile without being childish, her flesh was firm yet soft, she appeared tall or short according to the moment, her feet were equal to her hands. The sight of this enchanting girl, while with one knee next to her cheek she was attending to the toe-nails of one foot, was, as the Michelin guide says, worth not only a detour but a journey of its own.

—Translated from the Italian by Ann Goldstein

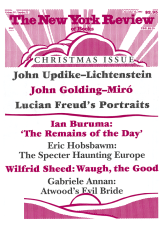

This Issue

December 16, 1993