1.

The mystery of Oswald subsumes the enigma of Jack Ruby. Yet if the first mystery has haunted the American intelligence establishment with the fear that it is implicated, Jack Ruby buggers reasonable comprehension for the rest of us. A minor thug from the streets of Chicago with a mentally unbalanced and often hospitalized mother, he has Mob connections. While they are no more impressive than those cherished by a hundred thousand other petty hoodlums in fifty American cities—which is to say, connections so tenuous and yet so familial that one can make a whole case or no case out of the same material—he has grown up among the Mob, and is on a first-name basis with Mob figures of the middle ranks. He is of the Mob in the specific values of his code, and yet never a formal member in any way—too wacky, too eager, too obsessed with himself, too Jewish even for the Jewish Mob. All the same, he is pure Mafia in one part of his spirit—he wants to be known as a patriot in love with his country and his people. He is loyal. Select him and you will not make a mistake.

We all know his famous story or cover story. He was grief-stricken by the death of JFK, so bereaved that he shut down his strip-joints for the weekend, and was so appalled at the possibility that Jacqueline Kennedy might have to come to Dallas to testify in Oswald’s trial that he decided to shoot the accused—“the creep,” as he would call him. But only at the last moment did he so decide. No premeditation. At 11:17 on Sunday morning, after waiting on line at a Western Union office to send $25 to one of his strippers who was desperately in need of money, he crussed the street, went down the ramp into police headquarters, and ran smack into Oswald, who was being filmed by TV cameras in the basement as he walked with his police escort to a car that would take him to the County Jail. There, imprinting the American mind forever with the open-mouthed expression of the victim and the squint-eyed disbelief of his guards, Ruby killed Oswald. Never before in history was a death witnessed by so many people giving full attention to their television sets. Much of the world now believed that Ruby was a Mafia hit man. The logic of such an inference suggested a conspiracy not only to kill Kennedy but Oswald as well, because he knew too much.

The concept, clear as a good movie scenario, ran into one confusion that has never been resolved: Why was Ruby standing on line in Western Union waiting his turn to send $25 to a stripper while time kept floating away and Oswald might be moved at any moment? The question could not be answered. How many confederates—and most of them had to be police—would be necessary to coordinate such a move? No one who is the key figure in a careful schedule that will reach its climax just as the target is being transferred is going to be found dawdling across the street at a Western Union office with only a few minutes to go. It would take hours for a stage director to begin to choreograph such a scene for an opera.

Ruby himself would say in the last interview he gave before he died of cancer that there was no way he could have been part of any calculation to bring him there at just the instant Oswald passed unless “it was the most perfect conspiracy in the history of the world…the difference in meeting this fate was thirty seconds one way or the other.”1

So, the death of Oswald is filled with the groans of thwarted logic. Yet never on the face of it has a crime seemed to belong more to the Mafia.

In a brilliant book exploring the rifts within the American Establishment, The Yankee and Cowboy War, Carl Oglesby was the first to advance the notion that Ruby was trying to tell Earl Warren that the Mafia certainly did order him to commit the deed. If Warren would just fly him, Jack Ruby, back to Washington on that same day, he, Jack Ruby, could furnish Warren with all the truth and, to prove it, would take a lie detector test on the spot.

As one reads these declarations in Jack Ruby’s testimony, it is difficult not to believe that Oglesby is right. In the course of a half hour, Ruby repeats his request five times.

Mr. Ruby: Is there any way to get me to Washington?

Chief Justice Warren: I beg your pardon?

Mr. Ruby: Is there any way of you getting me to Washington?

Chief Justice Warren: I don’t know of any. I will be glad to talk toyour counsel about what the situation is, Mr. Ruby, when we get an opportunity to talk.

Mr. Ruby: I don’t think I will get a fair representation with my counsel, Joe Tonahill. I don’t think so…2

He disavows Joe Tonahill. He is all but saying that he cannot know whom his lawyer is working for.

Advertisement

In another minute, he repeats himself:

Mr. Ruby: …Gentlemen, unless you get me to Washington, you can’t get a fair shake out of me.

If you understand my way of talking, you have got to bring me to Washington to get the tests.

Do I sound dramatic? Off the beam?

Chief Justice Warren: No; you are speaking very rationally, and I am really surprised that you can remember as much as you have remembered up to the present time.

You have given it to us in detail.

Mr. Ruby: Unless you can get me to Washington, and I am not a crackpot, I have all my senses—I don’t want to evade any crime I am guilty of.3

Five minutes go by. They speak of other matters. Then Ruby pushes his request again, even takes it another step:

Mr. Ruby: Gentlemen, if you want to hear any further testimony, you will have to get me to Washington soon, because it has something to do with you, Chief Warren.

Do I sound sober enough to tell you this?

Chief Justice Warren: Yes; go right ahead.

Mr. Ruby: I want to tell the truth, and I can’t tell it here. I can’t tell it here. Does that make sense to you?

Chief Justice Warren: Well, let’s not talk about sense. But I really can’t see why you can’t tell this Commission.4

Well, he can’t. Not in Dallas. Ruby all but shrieks at them: You dummies!—can’t you see that I can’t tell it here? You people don’t run this town. You can’t protect me in Dallas. I’ll get knifed in my cell, and the guards will be looking the other way.

Mr. Ruby: …My reluctance to talk—you haven’t had any witness in telling the story, in finding so many problems?

Chief Justice Warren: You have a greater problem than any witness we ever had.

Mr. Ruby: I have a lot of reasons for having those problems… If you request me to go back to Washington with you right now, that couldn’t be done, could it?

Chief Justice Warren: No; it could not be done. It could not be done. There are a good many things involved in that, Mr. Ruby.

Mr. Ruby: What are they?

Chief Justice Warren: Well, the public attention that it would attract, and the people who would be around. We have no place there for you to be safe when we take you out, and there are not law enforcement officers, and it isn’t our responsibility to go into anything of that kind…5

Ruby tries to explain it to them in the simplest terms. “Gentlemen, my life is in danger.” Then he adds, “Not with my guilty plea of execution.” (He has been sentenced to death by a jury in Dallas.) No, he is trying to tell them: I will be killed a lot sooner than that.

Mr. Ruby: …Do I sound sober enough to you as I say this?

Chief Justice Warren: You do. You sound entirely sober.

Mr. Ruby: From the moment I started my testimony, have I sounded as though, with the exception of becoming emotional, have I sounded as though I made sense, what I was speaking about?

Chief Justice Warren: You have indeed. I understood everything you have said. If I haven’t, it is my fault.

Mr. Ruby: Then I follow this up. I may not live tomorrow to give any further testimony…the only thing I want to get out to the public, and I can’t say it here, is with authenticity, with sincerity of the truth of everything and why my act was committed, but it can’t be said here…

Chairman Warren, if you felt that your life was in danger at the moment, how would you feel? Wouldn’t you be reluctant to go on speaking, even though you request me to do so?

Chief Justice Warren: I think I might have some reluctance if I was in your position, yes; I should think I would. I think I would figure it out very carefully as to whether it would endanger me or not.

If you think that anything that I am doing or anything that I am asking you is endangering you in any way, shape, or form, I want you to feel absolutely free to say that when the interview is over.

Mr. Ruby: What happens then? I didn’t accomplish anything.

Chief Justice Warren: No; nothing has been accomplished.

Mr. Ruby: Well, then you won’t follow up with anything further?

Chief Justice Warren: There wouldn’t be anything to follow up if you hadn’t completed your statement.

Mr. Ruby: You said you have the power to do what you want to do, is that correct?

Chief Justice Warren: Exactly.

Mr. Ruby: Without any limitations?

Chief Justice Warren:…We have the right to take testimony of anyone we want in this whole situation, and we have the right…to verify that statement in any way that we wish to do it.

Mr. Ruby: But you don’t have a right to take a prisoner back with you when you want to?

Chief Justice Warren: No; we have the power to subpoena witnesses to Washington if we want to do it, but we have taken the testimony of 200 or 300 people, I would imagine, here in Dallas without going to Washington.

Mr. Ruby: Yes; but those people aren’t Jack Ruby.

Chief Justice Warren: No; they weren’t.

Mr. Ruby: They weren’t.6

In the pause, Ruby tries to inform them of the incalculable depth of the peril he feels:

Advertisement

Mr. Ruby: I tell you, gentlemen, my whole family is in jeopardy. My sisters, as to their lives.

Chief Justice Warren: Yes?

Mr. Ruby: Naturally, I am a foregone conclusion. My sisters Eva, Eileen, and Mary…

My brothers Sam, Earl, Hyman, and myself naturally—my in-laws, Harold Kaminsky, Marge Ruby, the wife of Earl, and Phyllis, the wife of Sam Ruby, the are in jeopardy of loss of their lives…just because they are blood related to myself—does that sound serious enough for you, Chief Justice Warren?

Chief Justice Warren: Nothing could be more serious, if that is the fact…7

At this point, Ruby begins to despair of reaching Warren with his message. He cannot know how great the odds are that Lyndon Johnson has already reached Earl Warren more than half a year earlier with an even more secret message—long gunman; no conspiracy; the calm and well-being of our country asks for nothing less. So Ruby, in all the lacerated but still functioning wounds of his sensibility, is beginning to recognize that his own agenda is hopeless. If he keeps talking this way and Warren does not listen to him, then the record of this testimony could open him and his family to Mafia reprisal. So he returns—he reverts—to the sound of his own music, his operatic cover story: he invokes the name of Jackie Kennedy.

Mr. Ruby: I felt very emotional and very carried away for Mrs. Kennedy, that with all the strife she had gone through—I had been following it pretty well—that someone owed it to our beloved President that she shouldn’t be expected to come back to face trial of this heinous crime.

And I have never had the change to tell that, to back it up, to prove it.8

Since he has already spoken of threats to his life and to his brothers and sisters and Warren will not take him back to Washington, he now has to remove all onus from the Mafia. So he brings in the John Birch Society, but vaguely…vaguely…No one can follow him now.

Mr. Ruby: …there is a John Birch Society right now in activity, and Edwin Walker is one of the top men of this organization—take it for what it is worth, Chief Justice Warren.

Unfortunately for me, for me giving the people the opportunity to get in power, because of the act I committed, has put a lot of people in jeopardy with their lives.

Don’t register with you, does it?

Chief Justice Warren: No; I don’t understand that.9

Back goes Ruby to Jackie Kennedy. It may not be very convincing, but at least it is a story that cannot be disproven. What with the way he has learned to talk, back and forth, in and out, about and around, nobody is going to get into his head and refute his tale.

Mr. Ruby: Yes…a small comment in the newspaper that…Mrs. Kennedy may have to come back for the trial of Lee Harvey Oswald.

That caused me to go like I did; that caused me to go like I did.

I don’t know, Chief Justice, but I got so carried away. And I remember prior to that thought, there has never been another thought in my mind; I was never malicious toward this person. No one else requested me to do anything.10

“No one…requested me to do anything.”

If a copy of this transcript gets out—and there are lawyers and lawyers’ clerks abounding in the halls of Ruby’s paranoia ready to rush to the wrong people with just such a text—he can always point to this line: “No one else requested me to do anything.”

It is so serious to him, and so godawful. He, Jack Ruby—a good and generous man who fought his way up from the Chicago streets into a decent existence, a semi-decent existence, anyway—is now going to be executed by the government, or else he will be killed by some Mafia minion, some prison guard or convict, in a jail he knows is not safe, because of a crime he did not wish to commit in the first place.

It is monstrously unfair to Ruby, thinks Ruby, and more unfair to his family. The people outside who will punish him if he rats on them are evil. And evil has no bounds, as Hitler proved. So, if Jack Ruby tries to explain to the Warren Commission that he was only an agent in the death of Oswald, a pawn for the Mafia leaders who passed the order down the line to the man who gave him the order, then there will be Mafia leaders rabid with rage because he tried to rat on them. In retaliation, they will yet kill all the Jews. The safety of the Jews always hangs by a hair, anyway.

Let us try to assimilate the reasoning. It is not that Ruby is insane. He is, however, all but insane: He has an even larger sense of the importance of his own life than did Oswald. If they kill Ruby, feels Ruby, then all of his immediate family and his larger family, world Jewry, is in peril. So he rallies for one more attempt:

Mr. Ruby: …it is pretty haphazard to tell you the things I should tell you…I am in a tough spot and I do not know what the solution can be to save me…I want to say this to you…The Jewish people are being exterminated at this moment. Consequently, a whole new form of government is going to take over our country, and I know I won’t live to see you another time.

Do I sound sort of screwy in telling you these things?

Chief Justice Warren: No; I think that is what you believe, or you wouldn’t tell it under your oath.

Mr. Ruby: But it is a very serious situation. I guess it is too late to stop it, isn’t it?11

He makes his very last attempt. How many times will he have to spell it out? Can’t they comprehend why he must get to Washington for these lie detector tests?

Mr. Ruby: I have been used for a purpose, and there will be a certain tragic occurrence happening if you don’t take my testimony and somehow vindicate me so my people don’t suffer because of what I have done.12

Yes, if I am killed, my people will be killed.

Mr. Ruby:…Because when you leave here, I am finished. My family is finished.

Representative Ford: Isn’t it true, Mr. Chief Justice, that the same maximum protection and security Mr. Ruby has been given in the past will be continued?

Mr. Ruby: But now that I have divulged certain information…13

He has spoken too much on this day, he is trying to tell Gerry Ford. His security will be affected. “I want to take a polygraph test,” he tells them, but “maybe certain people don’t want to know the truth that may come out of me. Is that plausible?”14

If Ruby is not out of his mind, merely all-but-insane—that is, highly disturbed but sane—then he really does seem to be saying that he acted as a hit man. Yet there is still the odd wait on line in the Western Union office. How to explain that?

We had better take a look at a few Mafia sentiments concerning Kennedy. Indeed, we are obliged to.

For months, through all of 1963, there had been low sounds rumbling down from the summits. Jimmy Hoffa, for one, was livid on the subject of the Kennedys. A legal counselor for Santo Trafficante, Frank Ragano, quotes Hoffa as saying, “The time has come for your friend and Carlos to get rid of him, kill that son of a bitch, John Kennedy…. No more fucking around. We’re running out of time.15 Hoffa is, of course, referring to Carlos Marcello.

Not only was there a host of rumors after November 22 that Trafficante, Marcello, and Hoffa had given the order to kill Jack Kennedy, but indeed G. Robert Blakey, Chief Counsel to the House Select Committee on Assassination, concluded that “elements of organized crime participated in the plot to assassinate President Kennedy” (although, certainly, no smoking gun was found).16

Recently, Frank Ragano’s book, Mob Lawyer, did offer one further line of dialogue, although no more can be claimed for such an item in relation to the assassination but that it is a teaser; yet Ragano does emphasize that Marcello and Trafficante certainly wanted Jimmy Hoffa to believe they were behind the assassination. “You tell him he owes me, and he owes me big,” said Marcello to Ragano,17 passing a message to Hoffa in impeccable Sicilian metaphor that a proper repayment for such a coup might be to receive a loan of $3.5 million from the Teamsters’ pension fund for investment in a lavish French Quarter hotel that Marcello and Trafficante wished to open. Ragano’s disclosure supplies no witness to their conversation but Trafficante (now dead).

Nonetheless, it stimulates one’s own imagination toward two hypotheses, each of which, for our purposes, can point in the same direction. An hypotheses, no matter how uncomfortable or bizarre on its first presentation, will thrive or wither by its ability to explain the facts available. These two hypotheses are able not only to live but to nourish themselves on the numerous details Gerald Posner gathered from various sources in his long and careful delineation of Jack Ruby’s movements during the three days, Friday, Saturday, and Sunday, of Oswald’s incarceration.18 Indeed, Posner’s chapter on Ruby may be the most careful and well-written section in his book.

Posner amasses these details to prove that Ruby was not acting under orders but was mentally unbalanced, and he gives us more than thirty pages of text as he follows Ruby’s behavior after the President’s death. It will be interesting, however, to use Posner’s carefully collected details to support an opposite point—that Ruby killed Oswald under orders from above.

2.

Let us take up our two hypotheses. The first, and larger, one is that Marcello and/or Trafficante did give an order sometime in September, October, or November to assassinate Jack Kennedy. Given, however, the solemnity of such a deed and the dangers surrounding such an attempt, the precautions employed to wall themselves off from the act would likely have been so thoroughgoing that the order had to pass through a number of cutouts, and each cut-out would only be able to identify the man who had given him his order. Be it said that the executive details of the assassination were left to people at the other end of the line—those who would do the deed. So great was the separation, in fact, that Marcello and/or Trafficante would not know the killer (or killers) or the date or the place. It could happen anywhere—Miami, Texas, Washington, New York—it would not matter. They would not be near any of the immediate details.

Immediately after the assassination of Kennedy occurred, they assumed—how could they not?—that it was the fulfillment of their order. When they learned, therefore, by way of radio and television reports, within the hour after Oswald was apprehended, that the suspect had lived in the Soviet Union, his fate would have been sealed. It is likely that with their encyclopaedic knowledge of everyone connected, even remotely, to their business, they would have known the name of Lee Harvey Oswald, because Lee’s uncle, “Dutz” Murret, the husband of Marguerite Oswald’s sister, was already familiar to Marcello because of this uncle’s ties to Nofio Pecora, one of Marcello’s lieutenants; moreover, it was no secret in New Orleans that the Murret family had been caused considerable embarrassment by Lee’s defection to the Soviet Union in 1959.

The association was loose but heinous. Oswald, by their lights, was not only some kind of Communist but could now be connected, no matter how indirectly, to Marcello. If Oswald had been the hit man, he could not be relied upon. And if he were innocent, that might be worse. There were too many variables. The problem had to be removed. A quick order was sent out: Put a hit on Oswald. This time they were in a rush, so there were probably not as many cut-outs; and more than one candidate for hit man in Dallas may have been selected, either in the way of locals or out-of-state professionals quickly dispatched there on Friday afternoon. Ruby—so this hypothesis would go—was one of the putative hit men. He was an amateur, a flake, and might be lacking enough dedication to pull off the job.

But Ruby would have been seen as having two advantages: He was, when all was said, a part of their culture—he would be afraid to talk—and he had the huge and unique advantage of access. For every soldier they made, the Mafia knew the characters and habits of a thousand men. So they also knew that Ruby was on good, friendly terms with at least a hundred Dallas cops. Ergo, Ruby could get to Oswald. He might not be the best man for the job, but he was certainly the one who would have the best chance of doing it in the shortest possible time.

Word, therefore, was passed to him by somebody he saw on Friday afternoon. It would be rank speculation to fix on Ralph Paul, Ruby’s oldest friend, a man then in his sixties, for Paul was gentle and had no more known relations to the Mafia than that he ran a restaurant in Dallas. Of course, it can be said that big-city restaurant owners are rarely without liaison to the Mob. Ralph Paul was also one of Ruby’s closest friends and was owed tens of thousands of dollars by Ruby—which the Mob would also have known. Ralph Paul could have delivered a message: “Kill Oswald and they will take care of you.”

If the question was how could Ruby do the deed and get away with it, the answer was that, with the right lawyer, Ruby would only receive a few years or, with a defense on grounds of insanity, might get away with no time at all. His financial condition could certainly be alleviated. His deep debts would be rearranged, and the money he owed to the IRS could be paid off. And for motive Ruby was furnished with a beautiful if crazy reason, or came up with the reason himself—which is even more likely—because the reason existed already as a kind of minor motive within him, a small infatuation: he was the kind of exceedingly sentimental man who would indeed have detested the pain it would cause Jackie Kennedy to testify in Dallas. Ruby had the first requirement for good stage performance—his emotions were quickly available, so available indeed that they kept intruding on his syntax, which is why his speeches to the Warren Commission are sometimes so hard to follow.

The above is the first hypothesis. The second is simpler. Marcello and Trafficante had made their noises back and forth with Hoffa about getting a hit on the President but, as Frank Ragano reported, they had issued no orders. They had merely fumed, and been afraid to make such a move. Yet when the President was killed, they had an opportunity to rake in some huge profits with Teamster funds, so they took pains to let Hoffa know that they had been the masterminds behind the deed. Indeed, Ragano hints at this likelihood in Mob Lawyer: “If there was a possibility of making big money, Santo and Carlos were capable of conning Jimmy into believing they had arranged the assassination solely for his benefit.”19 Now Jimmy could show his appreciation by diverting those Teamster pension monies into a loan for their hotel. The problem was Oswald. When he talked, assuming he would, Hoffa would be able to see that Marcello and Trafficante had had nothing to do with the death in Dealey Plaza. So Oswald had to be marked for extinction. Hypothesis One and Hypothesis Two may be at great variance, but they come to the same conclusion—given the need to move quickly: Jack Ruby is anointed to be a hit man.

That he did not see it as an honor is evident in his behavior. The assignment was equal to the total disruption of his life. Ralph Paul, if he was the last cut-out to Ruby, would have issued no personal threats, but then he would not have had to. To disobey that kind of order could prove considerably more damaging than the cost of doing the deed. Ruby could only guess who might have initiated such a project, but whoever the top man was, he would not be sitting far from the devil’s right hand.

If we are now in position to see whether the details collected by Gerald Posner conflict or agree with the common point of these two hypotheses, the first question to pose is when Ruby might have been given such an order. The earliest time that one can reasonably suggest, from the recorded evidence, is when he talked to Ralph Paul, at about 2:45 that Friday afternoon. It was only an hour and a quarter after the announcement of the death, but then the move from above could have been quick. Marcello and Trafficante may have been renowned not only for their caution but for their speed. That Ruby called Paul, and Paul did not call Ruby, is not a fatal objection: Ruby could have been passed a message to call Paul by one of the dozens of people he saw after he heard of the assassination.

Posner: The Carousel’s records show a call to the Bullpen [Paul’s] restaurant at 2:42 for less than a minute. When Ruby discovered Paul was not at the restaurant but instead at home, he telephoned him there. The phone record shows he called Paul at 2:43.20

Mr. Paul: …when I got home Jack called me and he said, “Did you hear what happened?” I said, “Yes; I heard it on the air.” He says, “Isn’t that a terrible thing?” I said, “Yes; Jack.” He said, “I made up my mind. I’m going to close it [the Carousel] down.”…

Mr. Hubert: Did he discuss with you whether he should close down?

Mr. Paul: No; he didn’t discuss it. He told me he was going to close down.21

Unless it was Paul who told him to. Ralph Paul, as the message bearer, could well have said: “Jack, you’ve got to close down for the next couple of days. You are going to need all your free time to find a way to bring this off.”

Posner presents evidence that would oppose such an assumption. Ruby is very emotional in the office of the Dallas Morning News after he first hears of the attack, and speaks already of how awful it is for Jackie Kennedy and her children. He is crying when he leaves the newspaper office. This, however, is only by Ruby’s own account to the Warren Commission: “I left the building and I went down and got my car, and I couldn’t stop crying…”22 But he may have been lying, particularly if he did not start crying until later that day.

In any event, he visits his sister twice that afternoon, and by then, if this thesis is of value, had probably been given the word. Certainly his behavior suggests much inner turmoil. His sister was ill in bed, having just returned to her home a few days before, following an abdominal operation, and he had gone out to shop for her.

Posner: Ruby was back at Eva’s by 5:30 and stayed for two hours.

Eva said he returned with “enough groceries for 20 people…but he didn’t know what he was doing then.” He told her that he wanted to close the clubs. “And he said, ‘Listen, we are broke anyway, so I will be a broken millionaire. I am going to close for three days.”‘ In dire financial straits, and barely breaking even with both clubs open seven days a week, his decision to close was an important gesture…

But his sister Eva witnessed the real depth of his anguish, and unwittingly contributed to it. “He was sitting on this chair and crying…. He was sick to his stomach…and went into the bathroom…. He looked terrible.”23

As she says to the Warren Commission:

Mrs. Grant: …he just wasn’t himself, and truthfully, so help me, [he said] “Somebody tore my heart out,” and he says, “I didn’t even feel so bad when pops died because poppa was an old man.”24

This, she indicates, is the worst state she has ever seen him in. From what she says he sounds more like a man who fears his own life may soon be ended than someone grieving over the assassination. It is all very well to take a shot at Oswald, but what if he, Jack Ruby, is mowed down in the process?

Once he left his sister’s house, he went over to police headquarters at City Hall, where Oswald was being interrogated. He never had had trouble getting in before, and now, given the exceptional influx of newsmen, there was no difficulty at all. From 6:00 PM on, he was there, expecting, but not knowing whether he would have, an opportunity to get near enough to Oswald to do the job.

Posner: John Rutledge, the night police reporter for the Dallas Morning News knew Ruby. He saw him step off the elevator, hunched between two out-of-state reporters with press identifications on their coats. “The three of them just walked past policemen, around the corner, past those cameras and lights, and on down the hall,” recalled Rutledge. The next time Rutledge saw him, he was standing outside room 317, where Oswald was being interrogated, and “he was explaining to members of the out-of-state press who everybody was that came in and out of the door…. There would be a thousand questions shot at him at once, and Jack would straighten them all out….” Soon several detectives walked by, and one recognized him. “Hey, Jack, what are you doing here?” “I am helping all these fellows,” Ruby said, pointing to the pack of reporters…

Victor Robertson, a WFAA Radio reporter, also knew Ruby. He saw him approach the door to the office where Oswald was being interrogated and start to open it. “He had the door open a few inches,” recalled Robertson, “and began to step into the room, and the two officers stopped him…. One of them said, ‘You can’t go in there, Jack.”‘

Ruby probably left police headquarters shortly after 8:30…25

He had failed in his first attempt. Now he made a quick trip to his apartment, where he found George Senator, his roommate, at home. Senator later stated in an affidavit that it happened to be the “first time I ever saw tears in his eyes.”26 Then Ruby went on to his synagogue. No surprise if he was ready to pray.

Posner: He cried openly at the synagogue. “They didn’t believe a guy like Jack would ever cry,” said his brother Hyman. “Jack never cried in his life. He is not that kind of a guy…”27

Yes, he will tell people, he simply cannot bear the thought of that beautiful woman, the former First Lady, Jacqueline Kennedy, being obliged to return to Dallas and testify. You pay your money and you take your choice, but as a betting proposition—with all due respect to Jacqueline Kennedy—it must be 18 to 5 that Ruby is thinking of himself. And if it were anyone but Jacqueline Kennedy, the odds might be 99 to 1 that he is brooding about no one but himself. All he has is his life, and it is being taken away from him. A precious gem, a ruby, is about to be thrown into the crapper.

After the synagogue, he went right back to police headquarters.

Posner: When he arrived at the third floor of the station, he encountered a uniformed officer who did not recognize him. Ruby saw several detectives he knew, shouted to them, and they helped him get inside. Once there, he said he was “carried away with the excitement of history.” Detective A.M. Eberhardt, who knew Ruby and had been at his club, was in the burglary-and-theft section when Jack “stuck his head in our door and hollered at us…. He came in and said hello to me, shook hands with me. I asked him what he was doing. He told me he was a translator for the newspapers…. He said, ‘I am here as a reporter’ and he took the notebook and hit it.”28

He has taken cognizance of the situation. He has not been a vendor in ball parks and burlesque houses and a street hustler for too little: he is laying the groundwork to become indispensable to any number of reporters. He never knows when the right door will open and the opportunity will be there. This is the field of operations, and he may have a chance to try again before midnight.

Posner: In less than half an hour, Oswald was brought out of room 317 on the way to the basement assembly room for the midnight press conference. Ruby recalled that as Oswald walked past, “I was standing about two or three feet away.”29

The challenge has to be equivalent to jumping for the first time into a quarry pool from a height of forty or fifty feet. And Ruby cannot take the step. All he has to do is pull out his gun and finish Oswald off, but he cannot make the move. It is, after all, a vertiginous leap.

He is sick at his own cowardice, even as all of us are when we fail to take that daring little jump which some higher instinct, or a bully, or a parent, or a brother, is commanding us to take.

Posner: In his first statement to the FBI, Ruby admitted he had his .38 caliber revolver with him on Friday night (Commission Document 1252.9). Later, when he realized that carrying his pistol might be construed as evidence of premeditation, he said he did not have his gun on Friday. However, a photo of the rear of Ruby, taken in the third-floor corridor that night, shows a lump under the right rear of his jacket. If he was a mob-hired killer with a contract on Oswald, he would have shot him at the first opportunity. Certainly, any contract to kill Oswald would not have been one Ruby could fulfill at his leisure. Yet when he had the perfect opportunity, with Oswald only a couple of feet away, Ruby did not shoot him.30

Posner may lack empathy here. Just because you are told to kill Oswald doesn’t mean you can do it. Indeed, Ruby may still be looking for some way to perform the act and yet get out scot-free. That is a fantasy, but then, he is not a professional killer. What he cannot stomach is that there seems no way he will be able to follow orders without paying a prohibitive price.

In the meantime, to cut the losses to his ego, he continues networking. Soon he is talking to Ike Pappas, a reporter for WNEW in New York.

Mr. Pappas: It was at this point that I ran into Ruby—the first time that I recall. He came up to me as I was waiting for [Henry Wade, the Dallas District Attorney] and he said…”Are you a reporter?” I said, “Yes.”…And he reached into his pocket, and he pulled out a card. It said the Carousel Club on it. And I was amazed. I didn’t know who he was or what he was. My immediate impression of him was that he was a detective. He was well dressed, nattily dressed, I imagine. [A little later] he said, “What’s the matter?” I said, “I am trying to get Henry Wade over to the telephone.” He said, “Do you want me to get him?”…I said, “Yes, I would like to have him over here.” And he went around the desk, over to Henry Wade on the telephone…31

Ruby is investing more and more of himself in a role that enables him to hang around the third floor, waiting to pick up a better opportunity. It helps that he loves the role. As long as he can live within it, he can, like an actor, feel vital and alive; he can keep the dread of his real mission apart from himself.

Once he leaves police headquarters, however, he has to pass through a Walpurgisnacht. He wanders back and forth to newspaper offices and takes sandwiches to the people working at KLIF. In between, he spends an hour in a car talking to a couple, Kathy Kay, a former stripper at the Carousel, and Harry Olsen,32 a policeman, and all three are talking in Olsen’s car about how terrible it must be for Jackie Kennedy. The stripper begins to weep and the men join her with a few tears. In the moil and meld of such mutual compassion for Jackie Kennedy, all three feel respect for each other, deep respect, and each expresses it so.

After more wandering through the Dallas night, Ruby goes back to his apartment and wakes up George Senator.

Mr. Senator: Yes; it was different. It was different; the way he looked at you…

Mr. Hubert: Had you seen him in that condition before?

Mr. Senator: …I have seen him hollering, things like I told you in the past, but this here, he had sort of a stare look in his eye…

Mr. Griffin: I didn’t catch that. What kind of a look?

Mr. Senator: A stare look; I don’t know…I don’t know how to put it into words.

Mr. Hubert: But it was different from anything you had ever seen on Jack Ruby before?

Mr. Senator: Yes.

Mr. Hubert: And it was noticeably so?

Mr. Senator: Oh yes.33

Ruby then calls up his handyman, Larry Crafard, at the Carousel, wakes him up, and drives the youth and George Senator out to a billboard in Dallas that says: IMPEACH EARL WARREN. Ruby had been very upset earlier that day when he saw an ad, taken out by a man named Bernard Weissman, in the Dallas Morning News alluding to Jack Kennedy as a Communist supporter. He is now convinced that the John Birch Society invented the name Weissman in order to blame the Jews.

Now he, Jack Ruby, will soon be one of the Jews being blamed for the death of Kennedy, even if he will only be blamed in the secondary sense that they have selected him to be the one to kill Oswald. So Jack Ruby, a Jew, will pay the second heaviest price. He is a scapegoat, just like the Jews in the Holocaust, and just like all Jews who will soon be blamed for the Weissman ad. In his distraught state, he takes photographs of the billboard—IMPEACH EARL WARREN—as if this is not only evidential material of some sort but may even prove sacramental for someone in his position. If he is acting a little loopy, well, very few hit men out on a mission are reputed to comport themselves as 100 percent sane.

It is daybreak on Saturday before he drops Larry Crafard off at the Carousel and the handyman promptly goes back to sleep on the sofa in Ruby’s office. Crafard has his revenge, however, by telephoning Ruby at 8:30 in the morning. There is no food for the dogs at the Carousel, he tells his boss. Ruby flies into a rage for having had his sleep disturbed and proceeds to chew Crafard out as he never has before. Indeed, his language is so personal that Crafard packs his stuff and takes off. He is angry enough or uneasy enough to hitchhike back home to Michigan.

Somewhat later that morning, we learn from Posner,

Ruby turned on the television and saw a memorial service broadcast from New York. “I watched Rabbi Seligman,” he recalled. “He eulogized that here is a man [JFK] that fought in every battle, went to every country, and had to come back to his own country to be shot in the back. That created a tremendous emotional feeling for me, the way he said that.”34

Ruby is trying to find impressive reasons for his intended act. He is too big a man to do such a job just because the Mob has ordered it; no, he is potentially an honorable Jewish patriot who wishes to redress a wrong in the universe. We should recognize that Ruby, now that he has been given his assignment, does not have to justify it with Mob motivations or by Mob professionalism—“I’m there to do the hit, that’s it”—no, Ruby, being an amateur, would look to ennoble his task.

In any case, he seems to move without large purpose until mid-afternoon, when he goes to Dealey Plaza. As he sees the multitude of wreaths laid out for Jack Kennedy in the plaza, he weeps in his car, or so he testifies.

Posner: When he left Dealey Plaza, it appears Ruby once more went to the third floor of the police headquarters, expecting an Oswald transfer that never took place. He later denied being there Saturday because, again, he probably feared it might be interpreted as evidence of premeditation. The Warren Commission said it “reached no firm conclusion as to whether or not Ruby visited the Dallas Police Department on Saturday.” Yet credible eyewitness testimony shows he was there.35

He is still looking and he is still weeping. Ruby must have wept and/or had tears in his eyes ten to twenty times from Friday to Sunday. But, we can remind ourselves once more, he is bound to be crying for himself. His life is slipping away from him. Nevertheless, to maintain some finer sense of himself, he is also weeping for Jack, Jackie, and the children.

Soon enough, he begins to prowl again:

Posner: …Later in the afternoon [TV reporters in their van] saw him on their monitors wandering the third floor of police headquarters and approaching Wade’s office, from which regular reporters were barred.36

Indeed, he is hyperactive:

Posner: Thayer Waldo, a reporter with the Fort Worth Star-Telegram, watched Ruby giving out Carousel cards to reporters between 4:00 and 5:00 PM. He was aggressive in getting the reporters’ attention, pulling the sleeves of some and slapping others on the back or arms…Ruby said…”Here’s my card with both my clubs on it. Everybody around here knows me…. As soon as you get the chance, I want all of you boys to come over to my place…and have a drink on me…”37

Half of the time he is even behaving as he would if his life were to go on just as it used to. Talking to the reporters. he seems to have forgotten that he has closed the Carousel. He is living in two states of being. He is in his own skin and he is also playing the lead in a film full of significance and future heartbreak.

That Saturday night, with Oswald locked in his jail cell on an inaccessible floor, begins another long dark journey. Ruby has failed to produce, and it is a reasonable assumption that they will soon be letting him know about it.

Posner: By 9:30 Ruby had returned to his apartment. There, he received a call from one of his strippers, Karen Bennett Carlin, whose stage name was Little Lynn. She had driven into Dallas from Fort Worth with her husband and wondered if the Carousel was going to open over the weekend, because she needed money. “He got very angry and was very short with me,” Carlin recalled. “He said, ‘Don’t you have any respect for the President? Don’t you know the President is dead?…I don’t know when I will open. I don’t know if I will ever open back up.”‘38

How can he? If he does not kill Oswald, the Mob, after breaking his nose, his chin, and his kneecaps, will proceed to take his clubs away. Yet if he succeeds, the government will seize the Carousel. At 10:00, he telephones his sister Eva to complain about how depressed he is.

An hour goes by, and then he calls Ralph Paul. No answer.

Posner: Ruby telephoned [Paul’s] restaurant again at 11:18 and discovered Paul had gone home. He then telephoned Paul three times at home, at 11:19 for three minutes, at 11:36 for two minutes, and at 11:47 for one minute. Paul said he did not feel well, and told Ruby “I was sick and I was going to bed and not to call me.”39

That night, the Dallas jail received anonymous phone threats on Oswald’s life. On later reflection, Captain Fritz thought the calls might have come from Ruby. Perhaps they did. Ruby would have been looking for excuses—I had it all set up for Sunday, but they moved Oswald on Saturday night.

Now, he calls an old friend, Lawrence Meyers, who is in Dallas for a couple of days:

Mr. Meyers: …he was obviously very upset…he seemed far more incoherent than I have ever listened to him. The guy sounded absolutely like he had flipped his lid, I guess…

I said, Jack, where are you…He said come have a drink with me or a cup of coffee with me…I said, Jack, that is silly. I am undressed. I have bathed. I am in bed. I want to go to sleep but, I said, if you want a cup of coffee you come on over here and come on up to my room…He said, no, no, he had things to do. He couldn’t come over…This went on for a little while and the last thing I said, Jack, why don’t you go ahead and get a good night’s sleep and forget this thing. And you call me about 6 o’clock tomorrow night…and we will have dinner together and he said okay…

Mr. Griffin: …the FBI has quoted you as saying that one of the things that Ruby told you in the conversation was, “I have got to do something about this.” Do you remember that?

Mr. Meyers: Definitely.40

We can interpret that remark in two ways: I, on my own, have to do something about this; or, I have been told to do something about this.

He slept in one or another fashion that night and awoke in a terrible mood:

Mr. Senator: …He made himself a couple of scrambled eggs and coffee for himself, and he still had this look which didn’t look good…how can I express it? The look in his eyes?…

Mr. Hubert: The way he talked or what he said?

Mr. Senator: The way he talked. He was even mumbling, which I didn’t understand. And right after breakfast he got dressed. Then after he got dressed he was pacing the floor from the living room to the bedroom, from the bedroom to the living room, and his lips were going. What he was jabbering I didn’t know. But he was really pacing. 41

In the telephone conversation the night before, Meyers, referring to Jackie Kennedy, had said: “Life goes on. She will make a life for herself…”42

It was the worst thing Meyers could have said. By now, Jack Ruby and Jackie Kennedy are one—two suffering souls who have merged. Ruby does not want to make a new life for himself—he wants his old one back.

It is so painful. Ruby cannot ask directly for sympathy, but his self-love is pouring out of him. He is bleeding for Jackie Kennedy as if she is that beautiful element in his soul that no one else knows about, and soon it will all be lost.

He is distraught in still another fashion. When he woke up on Sunday morning, he must have been living with what he had learned the night before—Oswald was scheduled to be transferred at 10:00 AM. If he wasn’t at City Hall for the transfer, he might never have as good an opportunity at the County Jail.

Ruby, however, had decided not to be present. During the night, he had made up his mind. He would take whatever consequences would come from the Mob. Fuck them. He would not be their hit man.

Events, however, intervened.

Posner: At 10:19, while still lounging around the apartment in his underwear, he received a call from his dancer Karen Carlin…”I have called, Jack, to try to get some money, because the rent is due and I need some money for groceries and you told me to call.” Ruby asked how much she needed, and she said $25. He offered to go downtown and send it to her by Western Union, but told her it would “take a little while to get dressed…43

Then he went out. It was a little before 11:00 AM, and on his way he drove past Dealey Plaza and, according to Posner’s account, began to cry once more.

Of course, if you have been debating with yourself for close to forty-eight hours whether you are or are not going to pull a trigger, and either way death or utter ruin stands before you, you might cry too at every reminder of where you are. Which is that you didn’t take your last opportunity at 10:00 AM.

Oswald, however, has not yet been transferred. Captain Fritz has decided to let the press have one more look at him. A photo opportunity!

Meantime, Ruby is at the Western Union office sending $25 to his stripper. If his life is going to be smashed, he can at least do one last good deed.

Posner: …he patiently waited in line while another customer completed her business…When he got to the counter, the cost for sending the moneygram totaled $26.87. He handed over $30 and waited for his change while the clerk finished filling out the forms…Ruby’s receipt was stamped 11:17. When he left Western Union, he was less than two hundred steps from the entrance to police headquarters.44

Mr. Ruby: [I] walked the distance from the Western Union to the ramp. I didn’t sneak in. I didn’t linger in there.

I didn’t crouch or hide behind anyone, unless the television camera can make it seem that way…45

Posner: On the third floor of the headquarters, police had informed Oswald shortly after 11:00 AM that they would immediately take him downstairs…He asked if he could change his clothes. Captain Fritz sent for some sweaters…If Oswald had not decided at the last moment to get a sweater, he would have left the jail almost five minutes earlier, while Ruby was still inside the Western Union office. 46

Mr. Ruby: …I did not mingle with the crowd. There was no one near me when I walked down that ramp…47

It is worth hearing the account of a plainclothes man named Archer, a detective on the Dallas force:

Mr. Archer: …I could see the detectives on each side of Oswald leading him towards the ramp…I did have some bright lights shining into my eyes, and [it was hard] for me to recognize someone on the opposite side of the ramp [but] I caught a figure of a man…. I had been watching Oswald and the detectives…and my first thought was, as I started moving—well, my first thought was that somebody jumped out of the crowd, maybe to take a sock at him. Someone got emotionally upset and jumped out to take a sock at him, [but] as I moved forward, I saw the man reach Oswald, raise up, and then the shot was fired.48

Mr. Ruby: …I realize it is a terrible thing I have done, and it was a stupid thing, but I just was carried away emotionally. Do you follow that?

Chief Justice Warren: Yes; I do indeed, every word.

Mr. Ruby: I had the gun in my right hip pocket, and impulsively, if that is the correct word here, I saw him, and that is all I can say. And I didn’t care what happened to me.49

The irony is that he was indeed impulsive. He has probably been brooding upon the act since Friday; he has had his opportunities and not taken them. Now that he has lost his opportunity, or so he sees it, he has gravitated back to the police station. It has been the center of his activities for the last two days, after all. Yet, to his surprise, here and now is Oswald! It was as if God had put the man there. God was now giving the message: Jack Ruby was supposed to do it after all. So he fulfilled his contract. Let us say that he fulfilled two contracts. He did his job for the Mob, but since he had been talking about it so much that he had come to believe it, he did it as well for Jack, Jackie, the children, and the Jewish people. He fused himself into his all but unbelievable cover story and did it for Jackie Kennedy, after all.

To the Warren Commission, he describes his feelings with considerable style. Nothing is more difficult than to combine elegance with piety, but Jack has had seven months in jail to prepare this speech for Earl Warren:

…I wanted to show my love for our faith, being of the Jewish faith, and I never used the term and I don’t want to go into that—suddenly the feeling, the emotional feeling came within me that someone owed this debt to our beloved President to save her the ordeal of coming back. I don’t know why that came through my mind.50

He had been less sanctimonious, however, right after his gun was seized on that terminal Sunday:

Mr. Archer: …we took him on into the jail office and I assisted in keeping his left arm behind him and someone got his right. I couldn’t say who it was that had his other arm. Laid him down on the floor, his head and face were away from me at that particular time. But that is when I said, “Who is he?” [He answered] “You all know me. I’m Jack Ruby.”…And he said at that particular point, “I hope I killed the son of a bitch.”…I said to Ruby at that time, “Jack, I think you killed him,” and he just looked at me right straight in the eye and said, “Well, I intended to shoot him three times.”51

Posner: When they got to the third floor, Ruby, who was excited from the shooting, talked to anybody who came by. “If I had planned this I couldn’t have had my timing better,” he bragged. “It was one chance in a million…. I guess I just had to show the world that a Jew has guts.”…52

For forty and more hours before that, awake and asleep, he must have been castigating himself: You Jew, you do not have the guts to be a hit man—only Italians are that good. So he wanted to give the Mafia a real signature, his own—three shots—wanted to show the world that a Mobstyle execution was not out of reach for him, a Jew.

Jack Ruby would wear brass knuckles when he got into a fight in his nightclub. He would brag to his handyman, Larry Crafard, that he had been with every girl in his club, and yet…and yet…As with Oswald, there is always more to Ruby.

Mrs. Carlin: …He was always asking the question, “Do you think I am a queer? Do you think I look like a queer? Or have you ever known a queer to look like me?” Everytime I saw him he would ask it.53

A man of many sides—he loved his animals:

Posner: His favorite dog, Sheba, was left in the car. “People that didn’t know Jack will never understand this,” Bill Alexander [the Dallas assistant district attorney] told the author, “but Ruby would never have taken that dog with him and left it in the car if he knew he was going to shoot Oswald and end up in jail. He would have made sure that dog was at home with Senator and was well taken care of.”54

Yes, Posner must be absolutely right that Ruby was not planning to kill Oswald on Sunday at 11:21 AM. But that does not take care of why Ruby—for reasons that appear considerably closer to his heart than the pain and turmoil awaiting Jacqueline Kennedy—did the deed and threw the cloak of a thousand putative conspiracies over the mystery of Lee Harvey Oswald, his life and his death.

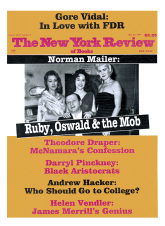

This Issue

May 11, 1995

-

1

Interview of Jack Ruby by Lawrence Schiller, 1996, Copyright © Alskog, Inc.

↩ -

2

Testimony given before the Warren Commission is hereafter abbreviated as WC Testimony. Vol. V, p. 190.

↩ -

3

WC Testimony, Vol. V, p. 191.

↩ -

4

WC Testimony, Vol. V, p. 194.

↩ -

5

WC Testimony, Vol. V, p. 195.

↩ -

6

WC Testimony, Vol. V, p. 196.

↩ -

7

WC Testimony, Vol. V, p. 197.

↩ -

8

WC Testimony, Vol. V, p. 197.

↩ -

9

WC Testimony, Vol. V, p. 198.

↩ -

10

WC Testimony, Vol. V, pp. 198–199.

↩ -

11

WC Testimony, Vol. V, pp. 208–210.

↩ -

12

WC Testimony, Vol. V, p. 211.

↩ -

13

WC Testimony, Vol. V, p. 212.

↩ -

14

WC Testimony, Vol. V, p. 212.

↩ -

15

Frank Ragano and Selwyn Raab, Mob Lawyer (Scribner’s 1994), p. 144.

↩ -

16

G. Robert Blakey and Richard N. Billings, Fatal Hour: The Assassination of President Kennedy by Organized Crime (Berkley, 1992), p. 145.

↩ -

17

Ragano, Mob Lawyer, p. 152.

↩ -

18

See Case Closed: Lee Harvey Oswald and the Assassination of JFK, by Gerald Posner (Random House, 1993).

↩ -

19

Frank Ragano and Selwyn Raab, Mob Lawyer, p. 151.

↩ -

20

Posner, Case Closed, p. 374, citing Warren Commission Exhibit 2303, Vol. XXV, p. 27.

↩ -

21

WC Testimony, Vol. XIV, p. 151.

↩ -

22

WC Testimony, Vol. V, p. 185.

↩ -

23

Posner, Case Closed, p. 376.

↩ -

24

WC Testimony, Vol. XIV, p. 468.

↩ -

25

Posner, Case Closed, p. 377.

↩ -

26

Posner, Case Closed, p. 378, citing affidavit of George Senator, November 24, 1963.

↩ -

27

Posner, Case Closed, p. 378.

↩ -

28

Posner, Case Closed, p. 379.

↩ -

29

Posner, Case Closed, p. 379.

↩ -

30

Posner, Case Closed, p. 379.

↩ -

31

WC Testimony, Vol. XV, p. 364.

↩ -

32

In the Warren Commission testimony, Harry Olsen’s name appears incorrectly as Harry Carlson.

↩ -

33

WC Testimony, Vol. XIV, p. 221.

↩ -

34

Posner, Case Closed, p. 384.

↩ -

35

Posner, Case Closed, p. 386.

↩ -

36

Posner, Case Closed, p. 387.

↩ -

37

Posner, Case Closed, p. 387.

↩ -

38

Posner, Case Closed, p. 389

↩ -

39

Posner, Case Closed, p. 390, citing WC Testimony, Vol. XV, pp. 672–673.

↩ -

40

WC Testimony, Vol. XVI, pp. 632–633

↩ -

41

WC Testimony, Vol. XIV, p. 236.

↩ -

42

WC Testimony, Vol. XIV, p. 236.

↩ -

43

Posner, Case Closed, p. 392.

↩ -

44

Posner, Case Closed, p. 394.

↩ -

45

WC Testimony, Vol. V. p. 199.

↩ -

46

Posner, Case Closed, pp. 394–395.

↩ -

47

WC Testimony, Vol. V, p. 199.

↩ -

48

WC Testimony, Vol. XII, p. 399.

↩ -

49

WC Testimony, Vol. V, p. 199.

↩ -

50

WC Testimony, Vol. V, p. 199.

↩ -

51

WC Testimony, Vol. XII, pp. 400–401.

↩ -

52

Posner, Case Closed, p. 398.

↩ -

53

WC Testimony, Vol. XIII, p. 215.

↩ -

54

Posner, Case Closed, p. 394.

↩