1.

The first paragraph of Dryden’s Essay of Dramatic Poesie records the great imperial moment in what the English call the Second Dutch War, and what the Dutch call the Second English War. A naval battle is taking place off Lowestoft, more than a hundred miles from London, but the sound carries as far as the capital. Dryden recalls:

It was a memorable day, in the first Summer of the late War, when our navy engag’d the Dutch: a day wherein the two most mighty and best appointed Fleets which any age had ever seen, disputed the command of the greater half of the Globe, the commerce of Nations, and the riches of the Universe. While these vast floating bodies, on either side, moved against each other in parallel lines, and our Country men, under the happy conduct of his Royal Highness, went breaking, little by little into the line of our Enemies; the noise of the Cannon from both Navies reach’d our care about the City: so that all men, being alarm’d with it, and in a dreadful suspense of the event, which they knew was then deciding, everyone went following the sound as his fancy led him; and leaving the town almost empty, some took towards the park, some cross the river, others down it: all seeking the noise in the depth of silence.1

That the battle of Lowestoft could be heard in London is confirmed by Pepys, whose diary for this day, June 3, 1665, records:

All this day, by all people upon the River and almost everywhere else hereabout, were heard the Guns, our two fleets for certain being engaged; which was confirmed by letters from Harwich, but nothing perticular; and all our hearts full of concernment for the Duke, and I perticularly for my Lord Sandwich and Mr. Coventry after his Royal Highness.2

And Pepys’s editors tell us that the sound of the gunfire was probably reflected by the stratosphere—“hence it was possible for guns firing in a s.-w. gale 120 miles to the n.e. to be heard in London.” But the battle was heard not only in London and Cambridge. It was also heard in The Hague. This was one of those intimate wars. Dryden uses the event in order to give a familiar historical setting for his fictional dialogue, much in the same way that Boccaccio evokes the plague in Florence at the opening of the Decameron. In both cases, it is the specificity of the description that makes it so riveting, and makes one wish that both authors had written more in their vein.

At that period, the river Thames at low tide formed rapids under London Bridge (a detail confirmed by Pepys), and in order to pass down river the boats had to shoot these rapids, at some danger. This is what is meant by the expression “shooting the bridge” in the next passage.

Taking then a barge which a servant of Lisideius had provided for them, they made haste to shoot the Bridge, and left behind them that great fall of waters which hindred them from hearing what they desired: after which, having disengag’d themselves from many Vessels which rode at Anchor in the Thames, and almost blockt up the passage toward Greenwich, they order’d the Watermen to let fall their Oares more gently; and then every one favouring his own curiosity with a strict silence, it was not long ere they perceiv’d the Air to break about them like the noise of distant Thunder, or of Swallows in a Chimney: those little undulations of sound, though almost vanishing before they reach’d them, yet seeming to retain somewhat of their first horrour which they had betwixt the Fleets….

It has been argued that what people were hearing in London on that day was indeed distant thunder, that they were victims of a mass delusion. But I have to say that I don’t believe this. Dryden seems quite right about the acoustics—one had to get away from the narrow streets of pre-Fire London, out onto the river or into the park; one had to get away from any other noise, one had to stop talking, and then one might begin to hear it, and it sounded like thunder but it didn’t only sound like thunder—it sounded “like swallows in a chimney,” that beautiful image which almost forces our assent.

We are reminded that in times of war, when life depends on it, the ear very quickly learns to make the most astonishingly fine distinctions between noises made by friend and foe, between types of weaponry, between warlike and unwarlike bangs. The people of London go out to listen to the noises, because their prosperity depends on it. If the noises get louder, that could spell defeat. But even if the Dutch retreat, as Pepys noted, it might be by cunning. Pepys is so cautious it takes him five days to believe that the Dutch have indeed been defeated. Then he gets a full report:

Advertisement

The earl of Falmouth, Muskery, and Mr. Rd. Boyle killed on board of the Dukes ship, the Royall Charles, with one shot. Their blood and brains flying into the Duke’s face—and the head of Mr. Boyle striking down the Duke, as some say.3

The last incident, the flying head of the son of the Earl of Cork hitting the future James II, found its way into a poem formerly attributed to Marvell, called “Second advice to a painter”:

His shatter’d head the fearless Duke distains

And gave the last first proof that he had Brains.4

But to return to Dryden and his wits on the river at Greenwich. They hear the noise receding and conclude that the English have won, which in turn is the cue for their dialogue to begin, which it does with the observation that the price of military victory is the amount of bad verse that will be written about it, that “no Argument could scape some of those eternal Rhimers, who watch a Battel with more diligence than the Ravens and birds of Prey; and the worst of them surest to be first in upon the quarry, while the better able, either out of modesty writ not at all, or set that due value upon their Poems, as to let them be often desired and long expected!”

The last remark seems to cover the case of Dryden himself, who, with admirable forbearance, waited more than a year before publishing his account of the Battle of Lowestoft in Annus Mirabilis. And here is how it begins, the same imperial moment evoked in poetry, after the vivid anxiety of the prose:

In thriving Arts long time had Holland grown,

Crouching at home, and cruel when abroad:

Scarce leaving us the means to claim our own.

Our King they courted, & our Merchants aw’d.Trade, which like blood should circularly flow,

Stop’d in their Channels, found its freedom lost:

Thither the wealth of all the world did go,

And seem’d but shipwrack’d on so base a Coast.For them alone the heav’ns had kindly heat

In Eastern Quarries ripening precious Dew:5

For them the Idumaean Balm did sweat,

And in hot Ceilon Spicy Forrests grew.The sun but seem’d the Lab’ror of their Year;

Each wexing Moon suppli’d her watry store,

To swell those Tides, which from the Line did bear

Their brim-full Vessels to the Bel’an shore.Thus mighty in her Ships stood Carthage long,

And swept the riches of the world from far:

Yet stoop’d to Rome, less wealthy, but more strong:

And this may prove our second Punick War.

Imperialist poetry was never clearer than this, never less drawn to circumlocution. Holland is doing very well, says Dryden, and therefore, like Carthage, it must be destroyed. And he goes on to give an account of that same battle of Lowestoft—excepting that the word “description” means something else, in the context of this kind of poetry:

Lawson amongst the formost met his fate,

Whom Sea-green Syrens from the Rocks lament:

Thus as an offering for the Grecian State,

He first was kill’d who first to Battel went.6

This from the same pen that brought us those swallows in a chimney! Sea-green Syrens on the rocks off Lowestoft! And what makes this description so impressively distinct from the facts as known is that Sir John Lawson didn’t even die in the battle—didn’t even earn that Homeric distinction of dying like Protesilaus, the first Greek to step onto the Trojan shore. He was wounded in the leg, and died a couple of weeks later in Greenwich. And he died, rather unpoetically, of gangrene. But since he was “vice-admiral of the Red,” and the senior officer to be killed in the engagement, Dryden drags him back through history to be the “precious thing” that is thrown into the sea when Britain, in the style of Venice, weds the Main.

The Dutch commander, Opdam as he is known in English (Jacob Obdam, Heer van Wassenaer), gets his in the next stanza:

Their Chief blown up, in air, not waves expir’d,

To which his pride presum’d to give the Law:

The Dutch confess’d Heav’n present, and retir’d,

And all was Britain the wide Ocean saw.

This is the imperial moment—it’s like lining up the three oranges. The money pours out of the machine and it’s all for me. Opdam is blown up. The Dutch see the hand of God in this and call it a day. Britain gains control of everything, the whole Ocean becomes Britain, and with it all the jewels ripening in the east, all the aromatics, and the teacups that survive the attempt at Bergen when

Advertisement

Amidst whole heaps of Spices lights a Ball,

And now their Odours arm’d against them flie:

Some preciously by shatter’d Porc’lain fall,

And some by Aromatick splinters die.7

In this kind of poetry, everything is at the disposal of the imperial purpose: teacups, chronology, spices, mythology. Reason itself lies down to have its tummy tickled.

And I think that in any company, even in Holland and even with descendants of Admiral Opdam in the audience, I could bring all this up without offense. It is baroque. It is preposterous. But it is not by any stretch of the imagination controversial. These barges shooting the rapids under London bridge, these men in wigs straining for sounds of war, these square-rigged ships all belong to another age. To the extent that they arouse our sentiments, they do so irrespective of national or imperial aspiration. I do not experience a flutter of the heart at the news of the success of the Duke of York at Lowestoft, any more than I feel outrage or shame or loss of honor at the sight of one of our ships’ prows, displayed as a trophy in the Rijksmuseum. The relics of these wars are part of a heritage we share with the Dutch.

Indeed, for the collector of medals who wishes to illustrate British history of this period, it is necessary to turn to the medals struck by the Dutch, which are anyway often superior to ours. The Embarcation at Schevingen, Admiral de Ruyter, Admiral Tromp, Ships Burnt in the Medway near Chatham, The Peace of Breda, and many more—these are the names by which desirable Dutch medals are known to British collectors, who treasure those poetic inscriptions which give a somewhat different spin to, for instance, the Action at Bergen already mentioned:

Dus wurt Brittanjes Trotz gestuÿt,

die zelfs bÿ Vriendt vaert op vrÿbuÿt;

en tergt de Noortsche Wallen.

Hÿ schaekt Vorst Fredricks haven recht

dog krÿgt Sÿn loon, door boeg en plecht

van Neerlandts donderballen.(Thus we arrest the pride of the English, who extend their piracy even against their friends, and who, insulting the forts of Norway, violate the rights of the harbors of King Frederick; but, for the reward of their audacity, see their vessels destroyed by the balls of the Dutch.)8

And those silver discs, with their remarkable evocations of the sea, those precious little Drydens in relief, lead up, of course, to The Embarkation of William of Orange at Helvoetsluys and in next to no time to The Battle of the Boyne of 1690 and the Pacification of Ireland and Ireland Subdued of the same year. And suddenly we find ourselves in a controversial world, the world that has been at bloody issue for the last quarter of a century. It was made by those same men in wigs, those same square-rigged ships, that same Duke of York, that same baroque, and it leads us, with one giant stride, straight into the millennium. When will Ireland be reunited? When and how will the conflict cease?

And this sudden controversy, this sudden baroque ambush of the modern, reminds us that there is always a nasty surprise in store for the imperial mind. It is typical of the imperial point of view that it is ignorant of, or blind to, the other. The imperial mind keeps missing the point. It fails to appreciate, for all its benevolence, why it might come under attack, why it might, for instance, be worth a nation’s while to rise up against it. The imperial mind has to be shocked out of its daydreams. It has to be subjected to some kind of demonstration that it cannot ignore.

This ability to look straight through a whole people, to fail to notice an indigenous population (as in the turn-of-the-century Zionist slogan which referred to Palestine as “a land without a people for a people without a land”), is on perfect display in Robert Frost’s “The Gift Outright,” a modern imperialist poem written, like Dryden’s, for purposes of state—in this case the inauguration of John F. Kennedy:

The land was ours before we were the land’s.

She was our land more than a hundred years

Before we were her people. She was ours

In Massachusetts, in Virginia,

But we were England’s, still colonials,

Possessing what we still were unpossessed by,

Possessed by what we now no more possessed.

Something we were witholding made us weak

Until we found out that it was ourselves

We were witholding from our land of living,

And forthwith found salvation in surrender.

Such as we were we gave ourselves outright

(The deed of gift was many deeds of war)

To the land vaguely realizing westward,

But still unstoried, artless, unenhanced,

Such as she was, such as she would become.

The repeated assertion of the colonials’ right to the land goes well with the sublime vagueness that anybody else’s right might be involved. Yes, there had to be deeds of war—“The deed of gift was many deeds of war”—but why or against whom we need not, on this occasion, consider. The point is rather to wallow in the metaphysics of the conceit that Americans, in order to become truly American and truly strong, had to yield to the land, surrender to it, instead of what you would expect from an account of a pioneering society—that they had to seize the land and bend it to their will.

What seduced Frost into writing such egregious rubbish, apart from the glamour of the commission, was the urge to assert the arrival of a new Augustan age, spelled out in the poem called “Gift Outright of ‘The Gift Outright”‘:

It makes the prophet in us all presage

The glory of a next Augustan age

Of a power leading from its strength and pride,

Of young ambition eager to be tried,

Firm in our free beliefs without dismay,

In any game the nations want to play.

A golden age of poetry and power

Of which this noonday’s the beginning hour.

One has to resist the thought that poetry like this represents its era. The desire to be the distinguished representative of the Golden Age is too high on the poet’s agenda. These lines were palpably foolish when written and remain so today. Nevertheless one can say for certain that Frost himself, had he miraculously hung on and been invited back, instead of Maya Angelou, for the Clinton inauguration, would have been alert enough to have sung a different tune. Something in time divides us from those days and from that rhetoric:

We see how seriously the races swarm

In their attempts at sovereignty and form.

They are our wards we think to some extent

For the time being and with their consent,

To teach them how Democracy is meant.

This goes so well with the Peace Corps, so well with the spirit which took responsibility for the destiny of South Vietnam, that I cannot help but match it with the quotation I saw on the wall of the American Embassy in Saigon as the embassy was being sacked. It was a line from Lawrence of Arabia, framed above the desk of someone who had been given that task of teaching the Vietnamese “In their attempts at sovereignty and form”: “Rather let them do it imperfectly than try to do it perfectly yourself. For it is their country, their war, and your time is short.”

If I ask myself what the last convinced imperialist poem might have been, taking the British Empire as its theme (and excluding Larkin’s “Homage to a Government”—which is an expression of unconvinced imperialism), I turn to a poem Eliot places among his “Occasional Verses,” with the following modest disclaimer:

To the Indians Who Died in Africa was written at the request of Miss Cornelia Sorabji for Queen Mary’s Book for India (Harrap & Co. Ltd., 1943). I dedicate it now to Bonamy Dobree, because he liked it and urged me to preserve it.

A man’s destination is his own village,

His own fire, and his wife’s cooking;

To sit in front of his own door at sunset

And see his grandson, and his neighbour’s grandson Playing in the dust together.Scarred but secure, he has many memories

Which return at the hour of conversation,

(The warm or the cool hour, according to the climate)

Of foreign men, who fought in foreign places, Foreign to each other.A man’s destination is not his destiny,

Every country is home to one man

And exile to another. Where a man died bravely

At one with his destiny, that soil is his. Let his village remember.This was not your land, or ours: but a village in the Midlands,

And one in the Five Rivers, may have the same graveyard.

Let those who go tell the same story of you:

Of action with a common purpose, action

None the less fruitful if neither you nor we

Know, until the moment after death, What is the fruit of action.9

Or: If you should die, think only this of you, That there’s some corner of a foreign field, that is forever both Birmingham and the Punjab (the Five Rivers Eliot refers to). You have a destiny, which happens, by some mysterious linguistic trick of mine, to take precedence over your destination. You must die at one with your destiny. I don’t know why this is, and nor do you, but we shall both find out the moment after our death.

The vein of preposterousness runs deep here—nothing in Dryden can match it—as an Anglican American addresses an audience, very few of whom would have been his co-religionists, and informs them that their deaths are required of them for reasons only his God can reveal. And for Eliot to write this at a time when the struggle for Indian independence was reaching its peak! Indeed, a part of the argument for independence after the Second World War was based on the fact that India had done its bit defending Britain and now it deserved something in return. So this adamant, metaphysical imperialism appears at the very moment of the Empire’s decline, and from the pen of an assimilated Briton, writing to please a Queen.

Now imperialism, which may be described as an immense intrusion into other people’s business, does not end when the imperialist decides to call it a day. One cannot simply announce: Okay chaps, the empire’s over now, and it’s time to put all that behind us. Much as everyone might like it, the empire does not simply collapse overnight. It collapses once. Then it continues to collapse. It breaks up once, then it breaks up again and again, and again. People’s lives are ruined by it. Nations are ruined by it. People are still on the move, because there was once an empire and now that empire is no more.

And this state of being forever on the move will not end just because, say, Hong Kong is returned to China or the few last outposts are closed down. It goes on and on. It has its own great scale, its epic proportions. What will happen to the Chinese empire itself is an added conundrum. The Indians who died in Africa take their place alongside the Indians who lived in Africa, until fairly recently thrown out. And they become, of course, the Indians who live in England, whose destiny, or destination, or both, is Birmingham.

Then there were the Indians who arrived in Fiji in 1879 on the Leonidas. Fiji at that stage had only been part of the Empire for five years. It had been offered to Queen Victoria as a way of resolving internal conflicts which looked as if they were going to lead to endless tribal bloodshed, and the British accepted the offer, not with great alacrity but as a way of forestalling the interest of any other great power. The administration of Fijian traditional society was carried out in a comparatively enlightened way—traditional landholdings were preserved and remain intact to this day. But there were also sugar estates, and these were in desperate need of labor.

The Indians who arrived in Fiji, mostly young Hindu men, had undertaken an agreement, or girmit, that they would work for five years, after which they became khula, free, but had to wait another five years before receiving their ticket home. And it is said that in many cases these young men were tricked—they had not realized, they hadn’t the remotest idea, how far Fiji was from Calcutta, where they embarked. They found that they had gone over the great sea, they had “crossed the black water,” and that in doing so they had lost caste and could never return. And certainly one might feel, after a ten-year wait, that there wouldn’t be much to return to.

This form of indentured labor, this euphemistic slavery, this shipping of Indians to Fiji, lasted until 1916—the year before “Prufrock.” But one wouldn’t say that the story of the Indians who went to Fiji ended there. From independence in 1970 until the late Eighties, the politics of Fiji was dominated by ethnic Fijians. Then for a brief time, a matter of weeks, a government was elected in which Indian and ethnic Fijian might share power. But the Fijian military put a stop to that experiment, and the Indians of Fiji were left under no illusions that any step they took to improve their lot made them that bit less welcome. And so they began to look, if they had resources or qualifications to do so, in the direction of, say, Vancouver. Their journey, they perceived, was not yet over. Where they lived, they lived only on tolerance, and that tolerance had worn thin and they began to be afraid.

At that time, when I was working in Fiji, I came across a group of ethnic Fijian soldiers and was invited to drink with them. They had a toast which went: “To the green grass of Fiji, which grew over the Great Wall of China, and fucked the Queen of England.” It occurred to me, as I contemplated this example of South Seas surrealism, that these people had a remarkable capacity to take the long view. The British had come and stayed a century. Now they were gone. The Indians were what was left, and might be expected, if suitably encouraged, to drift away before long. In the end it was the green grass of Fiji that would triumph over all.

2.

I’ve taken this single strand of the imperial story simply as an illustration of the unfinished nature of imperial business. If business is unfinished in people’s daily lives, how can we expect it to be finished in our culture, in our literature, in our poetry in particular? The word “post-imperial” is easy and comforting to use, since it seems to draw a line under an episode, to say That was Then and This is Now. But one supposes in fact that the nature of the post-imperial is only just unfolding, that there is more to this story than has yet been told. We should not expect to be entirely clear what this unfolding Now is like, or how it is going to behave in the future. We shall discover that in many ways we have been blind, or that we are still blind, to the most surprising number of interests and considerations, that our past, viewed from one angle as a boon, turns baneful with the very slightest shift of the light source.

The events of this late or post-imperial world have a habit of appearing in a rather puzzling order. It is not the case that the British Empire triumphed first, then collapsed in scandal and controversy, and that this controversy gradually died away as the years progressed. The British Empire triumphed and collapsed simultaneously; it was buried with full honors by the Commonwealth; then this dead empire went off to fight in the South Atlantic. We declared recently that we have no selfish or strategic interest in Northern Ireland. But we do have a selfish and strategic interest in Antarctica. We are a puzzling people, a puzzle to ourselves.

That sense, to use a phrase of Larkin’s from another context, “of failure spreading back up the arm” comes to us when we contemplate the shrinking patria to which we were born. We wonder: Where will the shrinking end? What will the real post-imperial country turn out to be? My guess is that it will correspond roughly to that part of the country which was conquered by the Romans, up to Hadrian’s but not the Antonine Wall. Until we see what will happen, though, how can we know to describe ourselves? How can we confine the cultural unit to which we belong?

For we live in an age in which the pressure is all toward self-definition, self-description of some kind. It wasn’t always like this. The poets who grew up on The Waste Land thought of themselves as urban, restless, international. The notion that he might have his roots in Birmingham struck Auden as absurd. He had his mythic patria in the wilds of a mythic Cumberland, but he knew this to be a fiction of his own making. As for turning his verse out for the sake of the Empire, nothing could have struck Auden—or his generation—as more absurd.

Well, events in this case took that typically puzzling order, for after his resounding success as Mr. Rootlessness, Eliot racinated himself. He found his metaphysical center:

…A people without history

Is not redeemed from time, for history is a pattern

Of timeless moments. So, while the light fails

On a winter’s afternoon, in a secluded chapel

History is now and England.10

And this, rather than his advice to the Indians, was Eliot’s true spiritual contribution to the war effort. One wonders whether, for Eliot’s American readers, such lines do not somehow smack of a kind of treachery. Certainly Four Quartets was not taken to heart in America as a supreme achievement in the way that it was, perhaps still is, in this country. People of my age were brought up on stories of the excitement felt as each of the Quartets came out in pamphlet form. And I suppose that a line such as “History is now and England” has a rhetorical force that lifts it, naturally, out of its context in the poem, and gives it a function as a slogan for the war. One notices that the line would never have worked if it had been “History is now and Britain,” or if Little Gidding had shifted a few miles and Eliot had been obliged to write “History is now and Wales.” In rhetoric, England could stand for the whole political, cultural unit. This is what hegemony is all about.

Today’s poet will be alert to the great problem of deploying the word “England,” or “English,” in such a rhetorical way. Such words are hedged around with taboo, and if we use them we expect to check very carefully for nuance. And if we do not know for sure what is the future of Britain, we will take care over “Britain” and “British” as well. But it was not always thus. There was a time when, given the belief that empire was an absurdity and “all that was in the past,” a poet like Douglas Dunn could write his “Poem in Praise of the British” confident that his ironies were shared:

The regiments of dumb gunners go to bed early.

The soldiers, sleepy after running up and down

The private British Army meadows,

Clean the daisies off their mammoth boots.

The general goes pink in his bath reading

Lives of the Great Croquet Players.

At Aldershot, beside foot-stamping squares,

Young officers drink tea and touch their toes.Heavy rain everywhere washes up the bones of British.

Where did all that power come from, the wish

To be inert, but rich and strong, to have too much?

Where does glory come from, and when it’s gone

Why are old soldiers sour and the bank’s empty?

But how sweet is the weakness after Empire

In the garden of a flat, safe country shire,

Watching the beauty of the random, spare, superfluous,Drifting as if in sleep to the ranks of memorialists

That wait like cabs to take us off down easy street,

To the redcoat armies, and the flags and treaties

In the marvellous archives, preserved like leaves in books.

The archivist wears a sword and clipped moustache.

He files our memories, more precious than light,

To be of easy access to politicians of the Right,

Who are now sleeping, like undertakers on black cushions.

That comes from Dunn’s first book, Terry Street, published in 1969.11 One could say of it that it takes nothing seriously, is unshockable and untroubled. The past is this wonderful absurdity. The politicians of the Right are not to be feared. We are living in this wonderful afterglow, and all is well.

One of the things one would not have guessed about Terry Street when it came out was that its author was Scottish. In fact, given that most of the poems in the book are about a working-class district of Hull, one might perhaps have supposed him English. “A Poem in Praise of the British” was untypical of its volume, but not untypical of the way Dunn later wrote at times, when he wrote as if he were expressing himself in French, in an easygoing, dandyish way which sometimes tempted him. But what is absolutely untypical of the later Dunn is the insouciance with which he treats the subject of empire. Within ten years, in the volume called Barbarians, which shows the influence of the hard, revolutionary Left, you find a poem called “Empires” which might almost have been written to remedy the defects in seriousness of the earlier one:

…They interfered with place,

Time, people, lives, and so to bed. They died

When it died. It had died before. It died

Before they did. They did not know it. Race,

Power, Trade, Fleet, a hundred regiments,

Postponed that final reckoning with pride,

Which was expensive.12

And so on. Soldiers are no longer funny. Empire is no longer an amusing mystery. By now, Dunn has begun to think of himself as a barbarian to identify with the victims of empire. And this phase gives way to a further phase in which, to a great extent, his Scottishness becomes his subject matter. He returns to his roots.

And one cannot help thinking that this increased emphasis on his nationality (if that is what Scottishness is), and on the seriousness of his history, comes not only as a result of the general rise of Scottish nationalism in the period, but also in part from a looking across the water at what was happening in Northern Ireland, both at the revived Troubles and at the assertive self-expression and self-definitions of the Northern Ireland poets. What had seemed to the young Dunn a natural way to begin—writing in England about England—had indeed once been natural. That was where he happened to live and work. Evident too in Dunn’s early work—on the surface, not buried obscurely—is the sense that the divide for him was between provincial life as a whole and that of the cultural metropolis, which was quite definitely London. But within a decade this had come to feel like a form of self-censorship or a suppression of one’s origins.

Now if the unfolding post-imperial patria were to turn out to be England alone as geographically defined—still no one would say that the clock had been turned back on the Empire, that all those stitches had been unpicked. The England that was left would contain the whole history of Empire within it, just as the history of the French empire has been incorporated within the map of France. An Irish nationalism or a Scottish or Welsh nationalism might have its vices as well as its virtues, but an English nationalism, when it raises its head above the level of absurdity, can only be sinister. We can remember that Rupert Brooke sitting in the Café des Westens in Berlin in 1912, and longing to go for a swim à la nature—and this already seems so sad, because Brooke was only a few stops on the S-Bahn from bathing places where he could easily have thrown off all his togs and leapt into “cleanness”—Brooke was depressed because he was surrounded by “Temperamentvoll German Jews.” Grantchester, the countryside around Cambridge, was longed for as being Judenrein. One can detect, in so many professions of love for England, some sinister implication of hatred for something else—hatred of other peoples, hatred of the world as it is becoming. If one cannot live without a sense of nationhood, one can love England for the complex thing it is and is becoming, not for some vicious conception of what it once might have been. The Dutch schoolchildren have a playground rhyme which goes:

Witte zwanen, zwarte zwanen.

Wie wil er mee naar Engeland varen?

Engeland is gesloten,

De sleutel is gobroken.

Is er dan geen smid in het land

Die de sleutel maken kan?(White swans, black swans.

Who wants to join the boat trip to England?

England has been locked.

The key is broken.

Isn’t there any smith in the land,

Who could mend the key?)

But if that question once had an answer, it seems to have been lost long since.

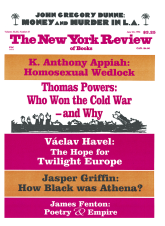

This Issue

June 20, 1996

-

1

Samuel Holt Monk, editor, The Works of John Dryden, Volume XVII (University of California Press, 1971), pp. 8-9.

↩ -

2

Robert Latham and William Matthews, editors, The Diary of Samuel Pepys, Volume VI (University of California Press, 1972).

↩ -

3

The Diary of Samuel Pepys, June 8, 1665.

↩ -

4

The Diary of Samuel Pepys, June 8, 1665.

↩ -

5

Edward Niles Hooker and H.T. Swedenborg, Jr., editors, The Works of John Dryden, Volume I (University of California Press, 1961), p. 59. Dryden’s own note reads: “In Eastern Quarries, &c. Precious stones at first are Dew, condens’d and harden’d by the warmth of the Sun, or subterranean Fires.”

↩ -

6

The Works of John Dryden, Volume I, p. 62.

↩ -

7

The Works of John Dryden, Volume I, p. 64.

↩ -

8

Medallic Illustrations of the History of Great Britain and Ireland, Volume I (London: Edward Hawkins, 1885; reprinted London: Spink, 1978).

↩ -

9

T.S. Eliot, Collected Poems 1909-1962 (London: Faber, 1963).

↩ -

10

Eliot, “Little Gidding,” in Collected Poems 1909-1962, p. 222.

↩ -

11

Douglas Dunn, Terry Street (London: Faber, 1969), p. 60.

↩ -

12

Douglas Dunn, Barbarians (London: Faber, 1979), p. 26.

↩