In response to:

The Devil in the Details from the September 19, 1996 issue

To the Editors:

In his review of David Irving’s Goebbels: Mastermind of the Third Reich [NYR, September 19] Gordon Craig astonishingly attempts to demonstrate that the book has merit despite its invidious purpose and dubious historical methods. Craig himself notes at the outset that Irving’s “obtuse and quickly discredited views…have proven to be offensive to large numbers of people.” Yet in his zeal to defend the right of historians to take controversial, even outrageous positions, Craig loses sight of their obligation to write history that is true.

No doubt, as Craig points out, Irving is an energetic researcher who has gained access to useful documents. But as in the past, Irving’s newest book deliberately distorts and obscures the facts in order to minimize the Holocaust and exonerate Hitler. Craig writes that “[s]atisfactory explanations of the deaths of the Jews are hard to come by” in Irving’s book, yet he praises Irving as knowing “more about National Socialism than most professional scholars in his field.”

It’s what David Irving seems not to know about National Socialism—namely Hitler’s deliberate murder of six million Jews—that is the problem.

Abraham H. Foxman

National Director

Anti-Defamation League

Gordon Craig replies:

The issue raised at the beginning of my article of September 19 was not the historian’s “obligation to write history that is true” but his freedom to express his views even if they are offensive, or appear to be false, to people like Mr. Foxman. Why he should have this freedom was explained succinctly and unanswerably by John Stuart Mill in the second chapter of On Liberty.

Mill wrote: “First, if any opinion is compelled to silence, that opinion may, for aught we can certainly know, be true. To deny this is to assume our own infallibility. Secondly, though the silenced opinion be in error, it may, and very commonly does, contain a portion of the truth, and since the general or prevailing opinion on any subject is rarely or never the whole truth, it is only by the collision of adverse opinions that the remainder of the truth has any chance of being supplied. Thirdly, even if the received opinion be not only true, but the whole truth, unless it is suffered to be, and actually is, vigorously and earnestly contested, it will, by most of those who receive it, be held in the manner of a prejudice, with little comprehension or feeling of its rational grounds. And not only this, but, fourthly, the meaning of the doctrine itself will be in danger of being lost, or enfeebled.”

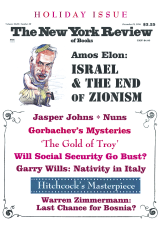

This Issue

December 19, 1996