The recent sentence to six years in prison of one of Tibet’s supreme monks shows Peking’s determination to dominate all events in the region and bring to an end a period of intense confusion within the Chinese Communist Party. For a brief time the regime apparently attempted a reconciliation with the Dalai Lama; but that possibility now seems out of the question.

During the first week in May it was announced in Peking that Chadrel Rimpoche, abbot of the Tashilumpo, one of Tibet’s main monasteries and the center for the Panchen Lama, Tibet’s second most important monk, had been imprisoned on April 21 for “splitting the country,” stirring up trouble within ethnic groups, leaking state secrets, and “colluding with the Dalai Lama.” The Rimpoche, as he is called, had been arrested last year, charged, with two accomplices, with giving the Dalai Lama a list of twenty-five small boys who were possible incarnations of the Tenth Panchen Lama, who had died in 1989. The Dalai Lama, from his Indian exile, subsequently designated one of the boys the Eleventh Panchen Lama. That boy, his family, and the Rimpoche soon disappeared.

By openly trying the Rimpoche and two other monks in a court in Xigadzi, the site of the Tashilumpo monastery, Peking has refuted the international charge that it makes its enemies vanish. What it has made plain is that the Chinese government alone will determine the shape of things in Tibet, thereby confirming its longstanding view that the region has always been a part of China. In reality, from the seventeenth century to the beginning of the twentieth century, Chinese control in Tibet was slight. And between 1912 and 1949 China had no control there at all. During the last three hundred years the Panchen and the Dalai Lamas were usually each other’s tutors, depending on which was older, although after 1923 the Ninth and Tenth Panchens came under Chinese control.

In the early 1960s, however, the Tenth Panchen Lama warned Peking that its policies were causing misery in Tibet; in 1964 he was detained by the Chinese for fourteen years. His death in 1989 was mourned by Tibetans as the loss of a great monk who had stood up to China.

China’s determination that it must have a part in the arcane process of discovering the child who would be the eleventh incarnation of the Panchen Lama prefigures its even greater determination to identify the eventual successor to the present Dalai Lama, aged sixty, whom it labels “the criminal splittist.” In the early Nineties, however, while Premier Li Peng, a hard-liner on Tibet, was ill, Peking agreed that the legitimacy of the Eleventh Panchen would be enhanced among Tibetans if the Dalai Lama approved his succession. In 1993 the Dalai Lama’s elder brother, who lives in Hong Kong, was given a letter in Peking saying that the Dalai Lama’s approval would be sought for the next Panchen. But in 1994, when Premier Li Peng resumed full powers, the cooperation with the Dalai Lama stopped.

It was around that time that a second letter, containing the twenty-five names of candidates for the Eleventh Panchen Lama, reached the Dalai Lama in India, probably from Chadrel Rimpoche and his fellow monks. The letter singled out as the most likely choice a six-year-old boy, Gedhum Choekyi Nyima; and he was publicly confirmed by the Dalai Lama. Peking promptly chose a different boy on the list, Gyaincain Norbu, from the same village, as the “authentic” Panchen, and in 1995 installed him in an elaborate traditional ceremony. Since then, the Dalai Lama has never again been called a “religious leader” by Peking, only a criminal.

Peking’s chosen Panchen Lama subsequently was given an audience with President Jiang Zemin, to whom he reportedly said, “Thank you and the Party. I will study hard to be a patriotic Living Buddha who loves religion.” Mr. Jiang urged the boy “to love socialism.”

As for the vanished Panchen, the Dalai Lama’s choice, Peking says only that he and his parents “are where they should be.”

—May 15, 1997

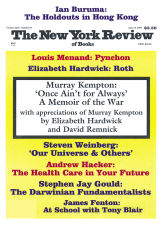

This Issue

June 12, 1997