In the time of Lyndon Johnson’s vice-presidential agony I found myself one day in his Capitol office listening to a Johnson soliloquy. Its central theme was his devotion to John F. Kennedy, but there were several lesser motifs. When Johnson was launched on one of these meditations, torrents of words poured out of him. On this occasion he canvassed the spectrum from the magisterial arrogance of Charles de Gaulle, to poverty in India, to his youthful career as a rural Texas schoolteacher. Always, however, the talk came back to his admiration for President Kennedy.

Johnson knew me only as a nameless face in the press gallery. In the middle of the monologue he surreptitiously, without interrupting the word flow, sent a note out to his secretary asking, “Who is this I’m talking to?” He was performing for an audience of one, and that one a stranger, but he probably thought some of it might just possibly turn up in a newspaper, and he was making it plain what the headline should say: Lyndon Johnson Utterly Devoted to John F. Kennedy.

To hear him tell it, there had never been a happier second banana. Never mind that the Kennedys had humiliated him when he tried for the presidential nomination in 1960. Never mind that the Kennedys’ glittering young courtiers—the “Harvards,” as Johnson called them—joked constantly and cruelly about him. Never mind that the press was calling him a forlorn figure who no longer mattered.

Never mind realities. On this day, playing to a nameless Capitol reporter, he spoke of the vice-presidential life as a friendship with a man he admired extravagantly. He told a story, not necessarily fictional, of an intimate dinner for three—Johnson, the President, and Jackie—in the Kennedys’ private White House quarters. Mrs. Kennedy had told him how greatly she and Jack needed him, how thankful they were for his help in lightening the presidential burden.

There was a tribute to the steely strength with which President Kennedy dispatched his enemies. He, Johnson, had experienced that cruel but manly strength himself when running against Jack for the nomination in 1960. He admired the way Jack had disposed of him so coolly, so dispassionately, without softness or irresolution.

My notes of this bizarre talk had quotation marks around the words “when he looks you straight in the eye and puts that knife into you without flinching….” This was Johnson’s metaphor for what Kennedy had done to him at the convention in Los Angeles. One was supposed to believe that Johnson now admired him for it.

It seemed doubtful that he truly admired Kennedy’s cool way with the knife. He was too proud, too vain, too thin-skinned. More likely, it still hurt so much that he couldn’t stop talking about it. It seemed probable that such a man who had been subjected to such an ordeal might bear a grudge for the rest of his life.

Praise John Kennedy to one and all though he did, Johnson had reasons to feel less than enchanted about their relationship. Here was greatness comically humbled. As Senate leader, Johnson had been the marvel of Washington. His mastery of the Senate amounted to genius, or so it was said by the Washington crowd, so quick to adore today’s hero, so ready to call him a chump tomorrow. “The second most powerful man in Washington,” the press had called him.

And what had John Kennedy done in Johnson’s Senate? He had been a mostly absent backbencher: an affable young fellow, to be sure, but rarely seen at the Capitol, not one to be taken seriously except for his father’s wealth. Everyone knew the old man was grooming Jack to be president, and real senators, serious men, the big mules, disdained senators whose presidential ambitions showed. “Always running for president,” they said of such men, with amused contempt.

Several senators were running for president in the 1950s, Lyndon Johnson among them, though he pretended almost to the end that he wasn’t. If you had the itch, good Senate form forbade you to let it show too early. Kennedy was something new. He didn’t care about good Senate form. By 1960 he had been running shamelessly and vigorously for four years. Real power in America lay in the White House, not in the Senate, he told anybody who bothered to ask why he was running. And of course, he was also being a dutiful son, trying to realize his father’s grandiose dream of putting a son in the presidency.

Johnson played a trickier hand. He was the conscientious statesman sticking to his job, doing his sweaty duty in Washington while Kennedy toured the landscape chasing the presidency. Johnson answered the quorum calls, shepherded the good bills to passage, killed the bad bills in their tracks, labored tirelessly for the nation’s good. He was being responsible. “Responsible” became a popular word among his camp followers. Johnson was betting that his dazzling senatorial skills would awe enough Democratic convention delegates to win him the nomination. It showed his profound ignorance of national party politics.

Advertisement

It was Kennedy who had it right. He let Johnson worry about the quorum calls and traveled the country courting local party captains; fighting in primaries and state conventions; jawboning governors, mayors, and union leaders, twisting their arms when necessary. If you seemed terribly young, it didn’t hurt to show you were a little tough.

He and brother Bobby and a passionately dedicated organization with seemingly unlimited financing cultivated the working politicians who constituted the party machinery. Johnson didn’t. The Kennedys made mincemeat of him.

There was an impromptu debate at the convention. Johnson talked of his tireless service in the Senate. Kennedy scarcely talked at all. He and Johnson had no disagreements on policy matters, he said, so the sensible thing would be for the party to put him in the White House and keep Lyndon in the Senate meeting those quorum calls. He sat down. The audience laughed, and Johnson was finished. Without flinching, Kennedy had put that knife into him.

Did Johnson secretly dislike Jack Kennedy? Not likely. It was impossible for almost anyone to feel a personal dislike for Jack Kennedy. What Johnson did dislike was the culture Kennedy represented.

The full Kennedy package—complete with Kennedys, advisors, thinkers, speech writers, professors, press cheerleaders, advance men, flacks, sycophants, and gofers—came bearing a sense of its own intellectual superiority. They had been to the best colleges, Harvard being the school of preference, and they were not slow to let you know they were an intellectual and cultural elite. The style was cool, polished, urbane. They admired wit and understatement. The women had finishing-school poise; the men favored muted pinstripes and buttoned-down collars. Most shared a feeling that the Kennedys were an entitled people.

They represented a culture that had been detested and feared in the South and West for a century. They looked not too different from the citified, hard-money crowd that William Jennings Bryan had once accused of crucifying the nation upon a cross of gold. Johnson’s political idol, Sam Rayburn, had long memories of New York and Boston money men squeezing the South and West to the edge of bankruptcy. Later Johnson’s presidency, far more liberal than Kennedy’s had been, would reveal how deeply his politics were rooted in the Populist movement of the nineteenth century.

So there were very old regional antipathies at work between Johnson and the Kennedys: rural populism versus Northeastern establishment. It wouldn’t have mattered if President Kennedy had lived. Johnson would simply have disappeared. A Johnson with presidential power might be more liberal than Kennedy, but he was still hard for the Kennedy culture to accept. They were contemptuous of him, as the hard-money Democrats of the Northeast had once been contemptuous of the rustic Bryan. Late in his presidency Johnson complained bitterly and often of the Northeasterners’ attitude.

“I always knew that the greatest bigots in the world lived in the East, not the South,” he told Richard Goodwin. “Economic bigots, social bigots, society bigots. Whatever I did, they were bound to think it was some kind of trick. How could some politician from Johnson City do what was right for the country?”

To Johnson, the Kennedy who represented everything hateful about the Northeast was Jack’s brother Robert, known to the public as “Bobby.” Bobby, in turn, saw Johnson as an unprincipled, lying yahoo. He ignored or insulted him as Jack’s vice president and, after the assassination, hated him as a usurper of Jack’s rightful power. The result was a personal feud that poisoned the Democratic Party for most of the 1960s.

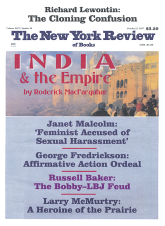

Mutual Contempt is an exhaustive and fascinating history of this nasty quarrel, which Jeff Shesol has assembled from the mountain of existing documents, books, and oral histories about the Kennedys and Johnson, and interviews of his own. Some of his freshest material comes from documents just now becoming available at the Johnson Library in Austin, including taped recordings of LBJ’s White House phone conversations.

Another valuable new book culled from the Johnson Library is Lyndon B. Johnson’s Vietnam Papers, edited by David M. Barrett. This is a generous collection of White House documents recording Johnson’s stubborn march to his doom. Since Bobby Kennedy was a major opponent of LBJ’s Vietnam policy, the Barrett collection is a valuable supplement to Mutual Contempt.

Shesol is twenty-eight years old. Not born until after the Johnson-Kennedy feud was long over, he is happily unencumbered by the prejudices of many still alive who were devoted to one or the other. The result is a remarkably evenhanded telling of a story that still makes many an old-timer’s blood boil. He will doubtless hear from a few of them complaining that he has got it all wrong. Having watched it from afar with no personal stake in the outcome, I think he gets it just about right.

Advertisement

Perhaps he is slightly off the beat about the Vietnam phase of the thing. He magnifies unduly the Bobby factor in Johnson’s decision not to run for re-election; early Senate doves like Fulbright, Church, Morse, and Gruening get short shrift, and Eugene McCarthy’s importance is almost entirely ignored. Richard Nixon’s role in undermining Johnson’s war policy is never mentioned. The fury of the great national debate that brought Johnson down gets lost in the smaller story of two of Bobby’s aides, Adam Walinsky and Peter Edelman, futilely trying to make him challenge Johnson on Vietnam.

For the most part, though, Shesol’s grasp of the era’s history is sure, his tale often entertaining, and his research awesome. Perhaps too much so for the casual reader. With books getting longer and longer these days, 475 pages may be tolerable for a good story like this about a minor historical spat. Still, one yearns for the pre-computer age when the laborious demands of typewriters and coldhearted editors held such books down to 250 pages carrying the reader rapidly from cover to cover.

Shesol’s narrative has four stages: (1) Bobby’s opposition to Johnson at the 1960 Democratic Convention, (2) Johnson’s refusal to make Bobby his vice-presidential candidate in 1964, (3) Bobby’s establishing a power base in New York from which to build a 1972 presidential campaign, and (4) Johnson’s self-destruction and Bobby’s decision to go for the presidency in 1968.

The Johnson-Bobby hostilities opened at the 1960 Democratic Convention in Los Angeles. John Kennedy asked Johnson to come on the ticket. Why is disputed. Bobby opposed the choice. Johnson surprised almost everybody by accepting. Bobby let everybody know he hated having Johnson on the ticket. Everybody included Johnson. Four years later LBJ would have the pleasure of denying Bobby the vice-presidential nomination on the 1964 ticket. (This irritating Washington custom of calling the gods by their nicknames, deplorable though it be, helps avoid a baffling confusion of Kennedys.)

Bobby was angry on several scores. One was Johnson’s eleventh-hour try for the nomination in 1960 after telling the Kennedys he would not run. Another was Johnson’s collusion in a scheme to stampede the convention galleries for Adlai Stevenson. If Stevenson could be used to block Jack’s nomination, maybe the convention would turn to someone else, maybe Lyndon Johnson. Jack, the instinctive politician, took the relaxed view that all this was just part of the game. Bobby, a moralist who disliked politicians, saw only a double cross.

Worst of all for Bobby, Johnson agents were raising troubling questions about Jack’s health. On the eve of the convention, India Edwards publicly declared that Kennedy had Addison’s disease and “would not be alive today if it were not for cortisone.”

“Malicious and false,” Bobby immediately replied. Obviously referring to Johnson, he said there were some Democrats who, “if they cannot win the nomination themselves,…want the Democrat who does win to lose in November.”

In fact, Kennedy did have Addison’s disease and was indeed dependent on cortisone, but Convention Eve was no time for the beguiling Kennedy candor. “Smiling broadly, boasting of his own ‘vigor,”‘ Shesol writes, Kennedy managed to “blithely outlast the mud-slinging which he regarded as part of the game of politics.” Jack was a good politician, Bobby wasn’t. “Unlike Jack,” Shesol writes, “Bobby blamed Lyndon Johnson.” He tells a story from Bobby Baker, Johnson’s closest Senate aide, about seeing Bobby at breakfast in the Los Angeles Biltmore:

When Baker suggested mildly that Ted Kennedy had been perhaps “a bit rough” in suggesting that Johnson had not fully recovered from his 1955 heart attack, Bob-by Kennedy’s face flushed red. “You’ve got your nerve,” he snapped, clenching his fists, leaning forward threateningly. “Lyndon Johnson has compared my father to the Nazis and John Connally and India Edwards lied in saying my brother is dying of Addison’s disease. You Johnson people are running a stinking damned campaign and you’re going to get yours when the time comes!”

A day or two later what Johnson got was the vice-presidential nomination.

Shesol has a low opinion of Bobby the politician. “Bobby was more a moralist than an operator, better suited to criminal investigations than Capitol Hill intrigue. And unlike John Kennedy, who treated fellow politicians with affable indifference, Bobby wore his contempt openly…. Politics was the dirty business Bobby did for his brother. It was, Bobby later scoffed, ‘a hell of a way to make a living.”‘

In retrospect, when the election returns showed Kennedy had beaten Nixon by a split hair, Bobby’s opposition to having Johnson on the ticket looked politically absurd. Without Johnson, Kennedy would almost certainly have lost Texas. Even with Johnson his Texas majority was only 50.5 percent. The ticket also carried six Southern states where Johnson’s down-home accent sounded more appealing than Kennedy’s high-velocity Bostonese.

There are many versions of how the Kennedy-Johnson ticket was created. Barrett’s Vietnam Papers records Johnson’s, as told eight years later. In 1968, three days after announcing he would not run again, he met with Bobby at the White House. Bobby wanted to know if Johnson would now oppose him for the nomination. Johnson finessed the question by talking about everything else. Walt Rostow’s notes of the conversation, included in Barrett’s Vietnam Papers, show Johnson was still brooding on the ancient history of 1960:

The President went on to say that in fact he had not wanted to be Vice President and had not wanted to be President. Two men had persuaded him to run in 1960: Sam Rayburn and Phil Graham [publisher of The Washington Post]. They had said that unless Johnson were on the ticket, John Kennedy could not carry the South. Without the South, Nixon would win. He would have greatly preferred to have continued to be the leader of the Senate.

The Vice Presidency is a job that no one likes. It is inherently demeaning….

One can see history being converted to humbug here. If Johnson had not wanted to be president, why did he fight for the nomination in 1960? Had he really wanted to remain Senate leader instead of becoming vice president? Possibly. He had seen the “demeaning” side of the vice presidency in Franklin Roosevelt’s treatment of another Texas vice president, “Cactus Jack” Garner, but he had also seen the vice presidency put Nixon in line for the White House. It is plausible that Rayburn and Graham were decisive in the matter. Whether they argued that only Johnson could carry the South no one else could truly say by 1968. Perhaps so. Or perhaps Johnson was adjusting history a bit to remind Bobby of how wrong he had been not to want LBJ on the ticket. And of course, Johnson was also saying that the Kennedys were in his debt. It is unlikely Bobby agreed.

As vice president, Johnson got to know what “demeaning” was. President Kennedy “tolerated no word of disrespect,” according to Shesol, but presidential will is often impossible to enforce. He put one of his closest aides, Kenneth O’Donnell, “in charge of the care and feeding of LBJ.” It was a poor choice.

O’Donnell was indifferent and offhandedly cruel…. Open disparagement of Johnson was rare, but O’Donnell’s demeanor typified what Johnson’s staff perceived as a “loose contempt” for the vice president by the White House staff…. O’Donnell’s arrogant disregard conveyed one simple, gleeful fact to the vice president: “We’re it and you’re not.” Robert Kennedy communicated as much when he barged in and interrupted Johnson’s private meetings with the president, launching into what he considered to be far more important business without so much as a nod of apology to LBJ.

Hickory Hill, Bobby’s estate in McLean, Virginia, was the social center for New Frontiersmen, whom Shesol calls “the Hickory Hill gang.” At their parties, “Johnson jokes and Johnson stories were as inexhaustible as they were merciless…. Partygoers asked, ‘Whatever happened to Lyndon?’ But no one could forget the galling fact that LBJ was in John Kennedy’s administration. He was, in their eyes, a gatecrasher, an anomaly, an embarrassment to the President, and a blight on the bright New Frontier.”

The assassination occurred. The world turned upside down.

Johnson’s accession was devastating to Bobby. Johnson feared Bobby’s response from the very beginning. Long afterward when he’d left the White House, he said Bobby’s decision to oppose him for the nomination in 1968 was “the final straw.” Thus Shesol:

“The thing I feared from the first day of my Presidency was actually coming true. Robert Kennedy had openly announced his intention to reclaim the throne in the memory of his brother.”

This may be nothing more than emotion recollected in tranquility, for everyone, but especially Bobby, was too shattered in those first few weeks to think Shakespearean thoughts of thrones lost and reclaimed. As Bobby slowly recovered, some in the Kennedy organization began a quiet campaign to make him Johnson’s running mate in 1964. Press speculation pumped steam into the campaign, and Washington was soon quarreling about whether Johnson had a duty to put the murdered President’s brother in the vice presidency. Opponents held that the campaign was asserting an arrogant Kennedy claim to a dynastic entitlement to high office.

The more interesting question was how Johnson would contrive to give Bobby the inevitable bad news. There was too much bad blood between them, too many old scores to settle. Bobby had been too candid about his contempt for Johnson. Johnson was not going to have him on the ticket, probably wouldn’t have had him on the ticket anyhow, because he wasn’t Johnson’s kind of politician, wasn’t a politician at all by Johnson’s standards.

Johnson’s genius for the devious produced a comically elaborate scheme for ending the Bobby boom. He announced that since no member of his Cabinet should be tainted by politics he would not choose any Cabinet member for the vice-presidential nomination. As attorney general, Bobby was a Cabinet member.

Johnson had him to the White House to explain that he could not let the purity of his Cabinet be stained by political involvements. Johnson later told reporters, “When I told him, he gulped.”

The irony of Johnson’s obscene and gaudy self-destruction is that he was guided by John Kennedy’s closest advisors (McNamara, Bundy, Rusk, Maxwell Taylor & Company) in a doomed attempt to fulfill John Kennedy’s grandiose inaugural pledge:

Let every nation know, whether it wishes us well or ill, that we shall pay any price, bear any burden, meet any hardship, support any friend, oppose any foe, to assure the survival and success of liberty.

As the end approached for Johnson, mired in Vietnam, he was discovering that, no, Americans would not pay any price, bear any burden, meet any hardship, and he didn’t know how to make them. He didn’t really know why he was there, and he didn’t know how to shake free without incurring political catastrophe at home. Foreign affairs had always been his weak point, and now he seemed drained of imagination and inventiveness. His genius was for domestic affairs, but now his grasp of domestic affairs failed him completely. The public was turning against the war policy in astonishing force, and he didn’t know how to deal with a public like that, a public on the edge of mutiny against a whole war. What had become of patriotism?

His experts, who had mostly been John Kennedy’s experts, counseled more and more war. More bombing, more troop commitments, more American participation in Vietnamese battles. Eventually the bomb tonnage dropped on Vietnam exceeded the tonnage dropped by all World War Two combatants on each other. His foreign policy advisors urged him to remember Munich. If the West had stood up to Hitler at Munich, World War Two might have been averted. Unless we stood up to communism in Vietnam…

What’s more, he was not going to be the first president to lose a war. He escalated, and escalated again. Death piled up around him, and still he plunged ahead, powerless to conceive of a way out. A pullout would bring out the Nixon Republicans crying about a Democratic surrender to communism. He’d lived through the brutal Republican campaigns charging Democrats with “twenty years of treason.” Nixon had been a leader in that pack, and Nixon was still out there itching to pounce.

The further irony is that Robert F. Kennedy should have played such an important role in finishing off this stubbornly faithful champion of his brother’s heroic rhetoric. Turmoil over Vietnam, a generational change, national fatigue with the cold war itself—something had become fundamentally different in the country. Johnson didn’t seem to sense it. If he did, he was powerless to respond to it. Bobby Kennedy seemed at times to sense something new in the political air, but he too was slow to respond. He had got himself elected senator from New York to secure a power base for a presidential campaign. But he was thinking of 1972. Obedient to the rules of the old politics, he thought it would be fatal to challenge a sitting president of his own party.

So he let his opportunity pass, and, early in 1968, with Johnson’s strength crumbling, Eugene McCarthy took it. Bobby’s younger advisers, who sensed the change taking place in their own generation, had urged and urged him to take on Johnson in 1968. He made some speeches disagreeing with the Vietnam policy, but his own thinking on Vietnam was still hawkish. The nub of it was that instead of bombing, we should be using counterinsurgency forces. Neither man seemed to understand that the Vietnamese were fighting a war for independence.

In March, McCarthy’s vote in the New Hampshire primary was big enough to show that LBJ was terribly weak. Worse for Johnson, McCarthy seemed likely to win the forthcoming primary in Minnesota, his home state. With the news of McCarthy’s New Hampshire showing, Bobby jumped at last. It was late, terribly late, maybe too late. It was McCarthy who had won the devotion of the young who should have been Bobby’s natural constituency. Many now regarded Bobby as a spoiler who had been too timid to fight against the odds, as McCarthy had. In consequence, Bobby was forced to fight McCarthy in a series of divisive primary elections. He had just won one when he was murdered in Los Angeles, for no apparent reason, by a Palestinian.

Rostow’s notes of the conversation between LBJ and Bobby three days after Johnson withdrew from the 1968 campaign say:

He wants Senator Kennedy to know he doesn’t hate him, he doesn’t dislike him, and that he still regards himself as carrying out the Kennedy/Johnson partnership.

Shesol thinks otherwise. “Kennedy did not fear Johnson,” he concludes, “Johnson feared Kennedy, and hated him for it.” He leaves no doubt that Kennedy hated Johnson to the very end.

This Issue

October 23, 1997