Every night of the year, no matter what the weather, two Coalition for the Homeless food vans travel around Manhattan distributing hot meals to people in the street—more than seven hundred meals every night, 250,000 a year. Business has been strong recently, particularly late in the month when welfare checks give out. How can that be? “We don’t see the homeless anymore,” friends say. Times are good, unemployment down. Who else could be out there but the mentally ill and addicts?

On a recent August night, one of the two vans circled lower Manhattan, starting at St. Bartholomew’s Church on Park Avenue. A few hungry people came by; the meal that night was a twelve-ounce cup of hot chili, a container of milk, an orange, and a piece of bread. At about seven o’clock the van moved on; some people asked for food while one of our vans was standing among the limousines opposite the UN Plaza Hotel; then it stopped for a much larger group, mainly men, near the East River. Most of them had been waiting, knowing that the van would come by.

Other stops were made on the way to the City Hall neighborhood where, in the Housing Court parking lot, there were two already organized lines—men to the left, women and children to the right, about eighty in all. The regular volunteers knew how to proceed, giving out five meals to those in one line, then five to the other. The parking lot is on the edge of New York’s Chinatown, but two new volunteers were not prepared for the sight of dozens of Asian women, half of them accompanied by infants and children, waiting patiently for their evening meal. The children carried thin plastic bags—the kind convenience stores use—for their dinner. Then they and their mothers, and often grandmothers, sat on the curb to eat while the chili was still hot.

Were they addicts, mentally ill? A few were, but most of the men, and all of the family groups, were neatly dressed, clean, and seemed alert and self-possessed. Some asked for second helpings of milk or bread, which the volunteers could not supply. They had four more stops that night. In fact the bread, which is gathered by City Harvest* at bakeries and restaurants around the city, gave out. Fraser Bresnahan, the Coalition van leader, said that “we never have enough bread.” Someone had been paying for eighty dozen bagels each Tuesday night, but he ran into difficulties and couldn’t go on.

Another stop, at Park Place, in front of City Hall. By then it was 8 PM, and most city officials had gone home, although there were still limos waiting alongside the curb. There were no children here, just grownups confident that a meal would arrive even if it was late. Sorry, no bread. No complaints.

The next major stop was in the shadows of One New York Plaza, home to one of the most prosperous investment banks. The van double-parked alongside the many limos waiting to take some of the hard-working executives home to their dinner. The chauffeurs knew the van, the volunteers knew the chauffeurs. The chauffeurs made no complaints that the van was blocking the street, as street folk drifted between their cars to pick up their evening meal. “Can I have the milk that the other fellow left behind?” asked one man, dressed in a clean summer shirt. One of the rookie volunteers said no, though as it turned out milk was in ample supply that night. He should have said yes.

The banking firm had been planning to go public, at a value of over $20 billion. Its employees seem friendly, well-disposed people. In fact some of the staff have worked as volunteers on the van. Enough bagels for both vans for one night each week would cost $8,000 a year. Oh well, it is really not the bankers’ responsibility.

Contrary to a common impression, the mentally ill account for only 25 to 30 percent of the vans’ clients. None of the volunteers that August night felt even remotely threatened, not even in the flophouses on the Bowery where the food was delivered upstairs to the common room.

What about the others, those neatly dressed men and women, some of them grandmothers accompanied by small children? What is so difficult for many of us to grasp is that large numbers of the working poor (who make up 20 percent of the people living in the city’s shelters for the homeless) simply do not earn enough to pay rent and buy food and other necessities. In New York, the median poor family spends over two thirds of its income on housing. An allowance from the city government to pay for shelter, if it is available at all, falls about $200 short of the minimal housing cost. And meanwhile the city, eager to save over $200 million on welfare expenditures, has left many with no support at all. On appeal to a review board, most of the adverse rulings of the welfare authorities are reversed; but in the meantime the family may be destitute.

Advertisement

Some of the cruelest blows were struck by the federal welfare reform bill enacted in 1996, the so-called Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Act. The bill severely cut back on food stamps. Large numbers of the elderly and disabled have been denied them entirely, even after the recent restoration of benefits for some legal aliens. For those who are still eligible, the benefit has been cut to 66 cents per person per meal.

Reducing welfare was seen as a major source of savings when Congress attempted to eliminate the deficit. The 1996 welfare reform bill trimmed $27 billion over six years from the food stamp program alone, over half of the total expected savings under the bill. The consequences of the reduced food stamp allowance for poor people got less congressional attention than the savings in the budget, but the effects are now becoming visible. The Journal of the American Medical Association, for example, reported recently on a Minnesota study of an alarming number of diabetics who could not afford to eat and were checking into Minneapolis hospitals with life-threatening complications. One of the doctors commented to the Journal, “Squeeze food stamps, and people can end up in the hospital.”

The Coalition’s cup of hot chili, milk, and fruit look better all the time. Those meals cost on average $1.80 each, even when most of the work of delivering them is done by volunteers. Of the program’s annual cost of $500,000, about 60 percent is funded by the state and federal government, with the balance paid by private donations. With that limited amount of money, the program is available only in Manhattan, where the population is more easily served. No Coalition vans travel to the four outer boroughs, where the city has pushed many of the homeless.

The House leadership has been advocating federal tax reductions of $70 billion. Is it too much to ask that a small part of last year’s federal surplus of about $71 billion be used to restore food stamp allowances and some of the other harshest cuts?

(The author is chairman of the Coalition for the Homeless, 89 Chambers St., New York, N.Y. 10007.)

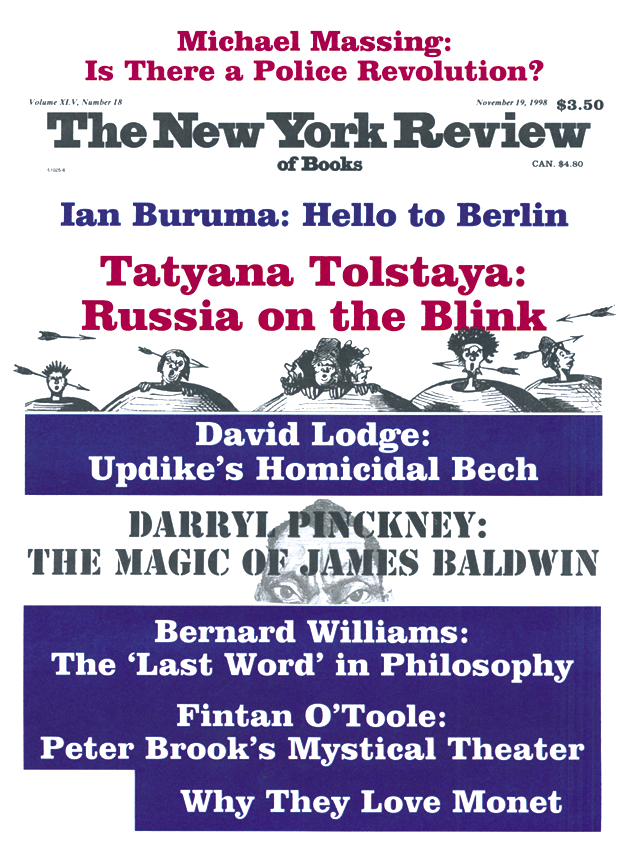

This Issue

November 19, 1998

-

*

159 West 25th St., New York, N.Y. 10001; (212) 463-0456. ↩