In October 1999 the London Guardian published an article by a columnist called Joan Smith. It was entitled “Death and the Maidens,” and its theme was that “we live in a culture that fetishizes dead women.” In the article Smith points to Marilyn Monroe’s suicide as the start of this phenomenon, but doesn’t go on naming names: so the Princess of Wales is spared, and so is her almost look-alike, the popular blond TV newscaster Jill Dando, who was mysteriously shot outside her home in a London suburb earlier last year. Her murderer has still not been identified, and her name and face continue to crop up in the British media, sometimes as “the second Diana.” Relentless coverage of the more recent murder of a Suffolk schoolgirl was the trigger for Smith’s piece.

The Austrian writer Ingeborg Bachmann might have identified the syndrome as a variation on her own obsessive theme: men murder women. She didn’t mean murder by shooting or stabbing or poison, but by cruelty and oppression. Her only completed novel, Malina, famously ends with the words “It was murder,” after the nameless first-person heroine, a writer, disappears surreally into a crack in the wall, leaving behind the man (or men) responsible for her death. One of these is the lover who left her; the other—possibly more immediately responsible because he has been breaking up her belongings—is—again only possibly—her alter ego.1 Few things in Bachmann’s novels are ever unequivocally clear: it is part of her trademark mystery. She herself died mysteriously and became and still is the kind of fetish Smith seems to have in mind.

She was a wonderful poet who also translated poetry and wrote, aside from Malina, radio plays, essays on literary subjects, opera libretti for Hans Werner Henze (who set some of her poems to music), short stories, and three unfinished novels. Characters from earlier works appear in later ones, and take turns at major and minor roles. She herself was a star, invited to lecture all over Europe, and to collect what sounds like a record number of literary prizes. A book of photographs of her (Ingeborg Bachmann: Bilder aus ihren Leben by Andreas Hapkemeyer2 ) was published in 1983 and reissued in 1997. It begins with snaps from her dim childhood in the dim Carinthian town of Klagenfurt near the Slovenian border (dim is how she saw it), and follows her metamorphosis into a chic, attractive Viennese; and finally into a woman who is still beautifully blond and well dressed, but has a disturbingly bloated face.

The photographs also reveal what a tireless participant she was in international writers’ conferences, symposia, and glamorous intellectual get-togethers of one kind and another, including a seminar organized by Henry Kissinger at Harvard in 1955, when she was twenty-nine. She appears smiling on group platforms and at outdoor café tables, surrounded by other Prominente of the artistic and literary world: Henze, of course; Paul Celan; Max Frisch, the Swiss writer who was her lover from 1958 to 1962; Roberto Calasso and his wife, Fleur Jaeggy; Günter Grass; Gian Carlo Menotti; Willy Brandt; Stephen Spender; and so on. Both her chic and her sociability are unexpected if all you know of her is her painful, introspective, haunted fiction, and her metaphysical poetry—metaphysical in the sense that John Donne and his contemporary poets were. Here is the first stanza of “Die gestundete Zeit,” from her first collection, published in 1953:

Harder days are coming.

The loan of borrowed time

will be due on the horizon.

Soon you must lace up your boots

and chase the hounds back to the marsh farms.

For the entrails of fish

have grown cold in the wind.

Dimly burns the light of the lupines.

Your gaze makes out in the fog:

the loan of borrowed time

will be due on the horizon.3

Still, Bachmann had a worldly side. She was like Elisabeth, the photographer-heroine of her novella Three Paths to the Lake (1972), who learns in Paris “that it was better to have three dresses by Balenciaga or some other great couturier…than twenty cheaper ones, and though she was obsessed by her work and thought of nothing but improving it, she acquired style, ‘class,’ as her German friend called it.”

Bachmann was always on the lookout for signifiers of class—lower, upper, and aspirationally on the move between the two. Like all Bachmann’s heroines—in her outward circumstances even more than most—Elisabeth is a self-portrait; and the story of her cosmopolitan life and loves is framed by a dutiful visit to her aged father in the family home near Klagenfurt. On the other hand, the love of her life—typically for Bachmann’s sophisticated literary games—is a man called Franz Josef Trotta, whom readers may—but don’t have to—recognize as a scion of the Trotta family from Joseph Roth’s famous novel The Radetzky March.

Advertisement

Bachmann died of burns in the intensive care unit of a Roman hospital in 1973, three weeks after a fire destroyed her apartment in the Via Giulia. She had lived in Rome for several years, having moved there from Zurich with Frisch. When he left her in 1962, she suffered a nervous breakdown and was treated in a psychiatric hospital. (She had briefly worked in one as a university student in Vienna, and she had studied psychiatry as well as philosophy.) The cause of the fire was not established; but Bachmann was a great describer of flames, in verse and in prose, and at least one of her heroines fantasizes about dying from a fall onto a lighted kitchen stove. So suicide theorists find their material ready-made, all the more so if they accept what Professor Karen Achberger says in her book on Bachmann: “The cause of death was not the burns, but the convulsions she suffered as part of the withdrawal symptoms from drugs she had been taking, which her doctors were unable to identify in time to save her life.”4

The two fragmentary novels translated by Peter Filkins, The Book of Franza and Requiem for Fanny Goldmann, are both case histories of nervous breakdown and part of a quartet Bachmann planned in the 1960s. Malina was the only one she completed. It too is about a nervous breakdown but not so much a case history as a surreal deconstruction. The fourth novel was to be about a woman called Eka Rottwitz who tried to commit suicide by jumping from a building when her lover left her, and ended up in a wheelchair. This draft was so fragmentary that it didn’t even make it into the 1978 edition of the collected works. The quartet as a whole was to be called Todesarten, and the critical edition of it by Monika Albrecht and Dirk Götsche5 runs to 3,055 pages in five volumes, mostly fragments and variora, material for any number of Ph.D.s.

Todesarten could be translated as “Ways of Death” or “Ways of Dying”; certainly not “Death Styles.” That bizarre Seventh Avenue label was chosen by Philip Boehm for the translation of Malina he published in 1991.6 In her book Achberger agrees that Death Styles won’t do: not so much because it is inappropriate in its context or just plain wrong—which it is—as because it doesn’t carry overtones of Brecht, as she thinks Bachmann intended. Nevertheless, she seems to feel she has to use it, presumably because Boehm’s is the only translation she can refer to.

Peter Filkins’s translations are not free from errors either. For instance, at a funeral in a Carinthian village church, the local parson preaches a Latin “sermon”—which would have been almost inconceivable in the 1970s; and anyway, Bachmann doesn’t mention a sermon at all, only mispronounced Latin and “Sprüche,” which could be biblical proverbs or just sayings. And when the coat-check attendant in a café addresses Fanny Goldmann as “gnä’ Frau” (dialect for “gnädige Frau“) Filkins translates that as “dear lady,” but that sounds much too courtly. “Gnädige Frau” is used all the time in German-speaking countries, a fossil term just as “ma’am” is in English, and both would be routine for a shop assistant talking to a customer, or a waiter (or coat-check) to a diner. This isn’t meant to be nitpicking: it’s just that both these examples (and there could be lots more) distort Austrian customs and ways of talking—however slightly.

The oddest misrepresentation comes in an explanatory note, which claims that members of student fraternities “swear lifelong allegiance to one another and the Austro-Hungarian empire, often by scarring their cheek with a sword.” It’s true that facial scars used to be taken as a sign of belonging to one of these prestigious fraternities, but they were got by fighting duels, not by scarring one another on purpose (though people were sometimes accused of doing that to themselves in order to fake an upper-class look).

In his Translator’s Note, Filkins says that drafts such as Franza and Fanny

provide a great deal of interest for scholars, as well as a window on to what Bachmann might have done to complete the novel if given the chance, so the question then becomes what to include and how to do it in a way that helps the novel to remain readable as well as a faithful “reading” of Bachmann’s intent.

In order to make them readable, he had to string together Bachmann’s posthumous fragments as best he could (this applies particularly to Requiem for Fanny Goldmann, onto which he has pasted two passages from the Eka Rottwitz draft). Even the order the novels themselves were to follow remains debatable. One might wonder, actually, for whom Filkins is translating. He speaks of “scholars,” but what Bachmann scholar would be unable to read German?

Advertisement

As for anyone else, the fragments are really too fragmentary to be enjoyable. Bachmann goes in for mystery, but the mystery here is partly not of her intention. Which bit comes before which? To what person or past event do Franza’s or Fanny’s thoughts refer? In Franza’s case it helps if you have read Bachmann’s short story “Das Gebell” (“The Barking”), which explains what led up to the psychological collapse she suffers all the way through The Book of Franza. The story has acquired a reputation for being Bachmann’s most accomplished piece of fiction.

In “Das Gebell,” Franza (here called Franziska), a girl from the Carinthian sticks, begins to study medicine in Vienna and gives it up to marry a famous psychiatrist called Leo Jordan—a conceited, snobbish, faux-upper-class tyrant who bullies and cows her, and neglects his mother. Franza visits her lonely mother-in-law every day and brings her delicacies. Then one day the visits stop. The old woman is bewildered, and so is the reader. The mystery is solved in the last pages, when Jordan brings his girlfriend Elfi Nemec to visit his mother and Bachmann casually drops the information that two years have passed since—an ending both neat and shattering. Elfi is a model, and reappears in The Book of Franza as a former girlfriend of Franza’s brother Martin.

The novel tells what happened to Franza when she stopped looking after old Frau Jordan. She has a nervous breakdown, brought on by Jordan’s bullying and the discovery of his affair with Elfi. He shuts her up in a psychiatric clinic. She escapes and joins Martin in the village where they spent their wartime childhood. Martin is much younger than she is, and a geologist. He is preparing a study trip to the Egyptian desert, and to his dismay Franza insists on joining him. She still suffers from convulsions and alternating bouts of raving and speechlessness. Their journey occupies the third and final section of the novel, an emotional travelogue homing in on the suffering of a postcolonial country: poverty, squalor, children trained to prostitution and begging, women overworked and abused, mad people manhandled. Bachmann returns to her favorite theme after the oppression of women by men: the oppression of one race by another, blacks by whites, Jews by Germans and Austrians. All of them are forms of fascism. Still, Franza’s health improves, until a stranger rapes her at the foot of a pyramid. Then she commits suicide by banging her head against its stones. The book ends with an inscrutable meditation on the flooding of the Nubian Desert by the Aswan Dam.

The Egyptian chapter reads like a long wail for Franza, for the Egyptian peasants, and for the ancient Egyptian dead, violated by white archaeologists. There are extraordinary evocations of the landscape:

They went into the desert. The light vomited down on them, the vomit of the sky, accompanied by a hot, clean smell. The great sanatorium, the great purgatory from which there is no escape, although it is open on all sides: no escape from it, Arabian, Libyan, with subdepartments, made of fine sand, stony, the stone polished by sand, bizarre stones, everything Saharan. The sanatorium had taken them in.

One passage seems to belong to a completely different genre—a typically disconcerting Bachmann switch. In Cairo, Franza consults an Austrian medical man who lives on a houseboat moored on the most desirable reach of the Nile. The villas and gardens on its banks are vividly described. Dr. Körner turns out to be a former SSdoctor who tried out euthanasia methods on female concentration camp inmates. Franza offers him an envelope containing three hundred dollars she pinched from Martin, and suddenly you realize that she is asking him to help her commit suicide. He refuses; and on her second attempt to see him, he has disappeared. The episode generates the kind of frisson you get from the best psychological thrillers—by, say, Dashiell Hammett or Raymond Chandler—and demonstrates what a virtuoso writer Bachmann could be in almost any genre.

She is at her most beguiling in the first of the three chapters from The Book of Franza, a flashback to Franza and Martin’s childhood in their grandparents’ village. Both the deaf old people are quite helpless in wartime conditions. So Franza constitutes herself Martin’s guardian, and drags him around with her wherever she goes. Their relationship is touching and funny: a mixture of loving protectiveness and exasperation on the sister’s side, of devotion and sexual arousal on the little boy’s. Fifteen-year-old Franza’s infatuation with a sexually unaroused but kindly and helpful British officer is described with immense charm and comic pathos.

In Requiem for Fanny Goldmann the comedy is social and therefore sharper and bitchier, all about class and snobbery—a mode at which Bachmann can compete with Proust. Fanny is born into an upper-class military family with anxiously concealed Nazi connections. Her mother and aunts are a high-comedy quartet of ladies in reduced circumstances. Her father, an army colonel, commits suicide because he is distantly involved in the Dollfuss murder. Fanny goes on the stage, becomes famous as “the most beautiful woman in Vienna,” and marries Harry Goldmann, a Viennese Jew who has emigrated and returned as cultural attaché of the American occupation troops. Harry is an oddly faceless figure, a benign silhouette—perhaps Bachmann never got around to filling in his features.

The marriage breaks up because Fanny is jealous of an actress whose talent Harry admires, even though he doesn’t love her and does love Fanny, who is beautiful but not particularly talented. Now in her forties, she takes up with Toni Marek, an as yet unpublished writer ten years younger than she is. Marek turns out to be an expensive toy boy and a shit, and before his first novel even appears, he has left Fanny and married a twenty-four-year-old German called Karin—a name Fanny considers ludicrously common. For a while, Karin insists on keeping up what she pretends is a warm, intimate friendship with Fanny—presumably because she is famous and has the entrée to the kind of society Toni aspires to.

When his novel is finally published, it turns out to be based on Fanny’s life as she told it to him when they were lovers. He describes their lovemaking and how she would wake up with bad breath. She feels violated, “butchered openly in public, a bleeding pig making small maddening shrieks. And so she lay in bed and released small maddening shrieks and drank and drank the cheapest alcohol she could find at the Bohrer delicatessen.” As she goes to pieces, her friends drop her. She tries to commit suicide and muffs it. Soon after, mercifully, she falls ill and dies.

Requiem for Fanny Goldmann is not so much a requiem as another long wail—another feminist wail, though the victim passivity of Bachmann’s heroines is very unlike the feisty feminism of today. Fanny is not a first-person narrative, but it is even more of a first-person experience than Franza, with Bachmann crawling into the innermost, frightening, shivery, disgusting crevices of Fanny’s collapse into alcoholism. It is an unbearable book, but one can’t stop reading it. Bachmann is a remarkable writer. One might want to complain of monotony or repetition in these works, but that’s impossible, because they are unfinished. So one must make the best of it and savor her astonishing prose mouthful by mouthful, paragraph by paragraph.

For it really is astonishing. Casual, catty, witty, it has an irresistible, sophisticated, idiomatic charm as it races along in paragraphs of Proustian length (deliberately broken up by Filkins in the cause of readability). Then it suddenly halts one in one’s tracks by juxtaposing words so unconventionally and unexpectedly that one feels the intense sensations they evoke have always existed but never before been let out of their cages. Here is Franza on the start of her collapse:

How do Ithink, how do I remember? No longer as I did in the past. It’s a force that moves through my head, that unrolls itself chronologically, presenting an accumulation of scenes, always the same ones, then I connect them. All I need is a ship’s cabin, a glass of water, and Ithink of a glass that was thrown past my head. But then there is more, the next one comes, there are shards of glass, then I arrive at my border, a wall, and I stand there and my lament carries through a large space, one like a desert, without onlookers, without confidantes, facing no one. You utter a word, and Imove with it and I am swept away on a flood of words that washes outward and upward from my head and then back again, breaking over my head. That’s how I remember. In a different way.

Bachmann is fiendishly difficult to translate, and Filkins nothing if not brave. But his translation bumps along—it has to—without her distinctive, private German rhythm and her myriad nuances. So it can’t quite convey either the charm or the spookiness that she so weirdly combines. She is probably one of those writers whom every generation will feel the need to retranslate.

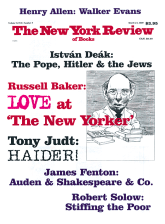

This Issue

March 23, 2000

-

1

See my review of Malina in The New York Review, March 5, 1992.

↩ -

2

Munich: Piper.

↩ -

3

From Songs in Flight: The Collected Poems of Ingeborg Bachmann, translated and with an introduction by Peter Filkins (Marsilio).

↩ -

4

Understanding Ingeborg Bachmann (Understanding Modern European and Latin American Literature) (University of South Carolina Press, 1995).

↩ -

5

Munich: Piper, 1995.

↩ -

6

Holmes and Meier.

↩