North of the Guggenheim Museum, New York’s Appian Way becomes quiet, intimate, and leafy. But inside the ornate mansion that houses the Jewish Museum, a powerful vision of the city’s Manichaean life, its perpetual dance of demolition and construction, unrolls across the walls of a ground-floor gallery. Since the late 1980s, the cartoonist Ben Katchor has been weaving dark, intricate graphic novels about New York—not the gleamingly visible metropolis of the recent booms, the bright archipelago of restaurants, clubs, and town houses, but its backdrop, the dark ocean of faded office buildings, fly-specked cafeterias, and discount stores.

Now a lively exhibition, crammed with Katchor’s scripts and rough drawings as well as with his finished strips, traces the development of his work, starting from his early drawings for Raw magazine and following the many strands of his current interests—which include graphic novels in black and white, elaborate one-page strips in color, and even the sets for a witty, award-winning opera, The Carbon Copy Building. In this cream-colored room, a grimy light-industrial Atlantis, submerged by recent history, comes to the surface.1

The inhabitants of Katchor’s city, sunk in deep middle age, dress in baggy, old-fashioned clothes and worry about their dry-cleaning bills. In the restaurants where they slump at tables and counters, food does not arrive drizzled with balsamic vinegar or dotted with pepper by contemptuous waitpersons. In the grocery stores where they shop, they do not find precious fish and perfect fruit heaped up in magnificent, glistening piles. The protagonist of many of Katchor’s strips—Julius Knipl, a middle-aged real estate photographer, who works out of a fly-infested office and spends long days waiting for the light to fall in just the right way on a run-down building—eats $1.29 breakfasts at luncheonettes and $2.50 dinner specials at cafeterias, where he wonders how the proprietors can provide two eggs, toast, and coffee or soup, goulash, vegetables, and dessert for so little.

Few of the buildings in this New York rise high. Along Katchor’s drab, dark streets, salesmen with pomaded hair lounge in the bright doorways of sleazy shops, hoping to sell cigarette-smoking bisque monkeys, novelty key chains, and hat bands that predict rain (Mr. Knipl, ever hopeful, takes a dozen, imprinted with his name at no extra cost). Mr. Knipl ransacks luncheonettes in the vain hope of finding one where he can order the cold drinks of his youth—a cherry lake, a Normona, a Latin cream, a Herbert water—from soda jerks who have no idea what he is talking about. He scrutinizes the runic signs and ponders the curious noises that show that light industry still survives; he racks his memory to determine if subways really once had underground luncheonettes, and men who slowly walked the tracks reading leather-bound books.

The strips that tell these stories have a distinctive texture. Katchor starts with words, writing and rewriting his texts before he begins to draw. And the words sprawl and leap across his finished pictures. The city, as he draws it, speaks, continually. Every façade and parapet bears a message. True, not all of these signifiers still have signifieds. High up on the walls of skyscrapers, signs too small to read reveal not the identity of offices but the hard-sell ingenuity of a sign painter in the distant past. Larger signs stick out from tenement walls, wooing customers for cheap businesses—like Moyel Brothers’ clothing store, the sign for which Mr. Knipl has seen and photographed from many angles and for many years, but when he tries to buy a jacket there the store turns out to have disappeared years ago. Even fragments of buildings—like a stately chimney, all that remains of the huge Progressive Laundry—testify to something, in this case, to the lofty character and standards of those who built the city that now decays around its melancholy prophet. Deftly rendered city noises—“Rumbaba,” says the subway, “Verrooo,” goes the siren—form an almost musical background.

The people who live in Mr. Knipl’s gray world also speak continually. They are urgent, articulate, obscurely desperate. “When the rich fornicate, the poor sweat,” cries a bespectacled prophet at the Garden of Eden cafeteria, where the few remaining readers of Sexual Progress magazine wait for the editor, Moishe Nustril, to come in and explain, over his late-night pie and coffee, that only sex can account for the massive injustice and inefficiency of the world: “Our days are ruled by our nights.” Long, melancholy narratives march above the images, grave and rhythmic as prose poems:

Mr. Knipl accidentally stuck his head into the past. Here was an untouched part of his office, where the heat of bygone summer days rose to be churned by a fan, where a distinctive molding caught the attention of a now long dead eye, and where luminous glass bowls hung in a turn of the century night. Mr. Knipl had heard of restoration efforts in the building to remove these ugly drop ceilings, but chose to preserve the past, undisturbed, by keeping his drop ceiling in place.

In this world of desperate little men, Willy Lomans metamorphosed into Henry James characters, those on whom nothing is lost, strings of words rattle swiftly past each other like old-fashioned model trains: exuberant catalogs of ingredients for cheap sauces, strange demands, wild explosions of eloquence. “The impresario of human drudgery has not yet been born,” says the owner of a theatrical ticket bureau, explaining why he cannot sell seats to those who enjoy watching laborers unload a truck or divert a stream of coffee. “A man forced into such a business”—so Mr. Knipl remarks, observing a vendor trying to sell balloons in the garment district and in front of the law courts, “no longer has the presence of mind to stop and consider the use of an 8 foot long balloon.”

Advertisement

The look of Katchor’s strips is as distinctive as their language. His characters prowl and gesture through a world steeped in shadows, which Katchor evokes with washes in many shades of gray on Xeroxes of the original pen drawings—urban claustrophobia rendered in chiaroscuro. As a boy in Brooklyn, Katchor steeped himself in the comics of the time—especially Spiderman, with its articulately neurotic protagonist who swoops dramatically through a city that he sees from rooftops and high windows. His own strips use the classic conventions of the comics: viewpoints shift constantly, moving from high above the scene of action to directly below the faces of those speaking. The reader hovers, dodges, lies on the ground, and floats high above it, all in four successive panels.

Katchor is not the first graphic novelist to dedicate himself to a lost Jewish world, or to the decline and fall of New York—Will Eisner and Harvey Pekar (whose texts are illustrated by others) had already done as much in the 1970s. In 1980, when Art Spiegelman and Françoise Mouly started Raw, which assembled European, Latin American, and American graphic novels, they led off with a magnificently leaden, apocalyptic vision of Manhattan in terminal decay by Jacques Tardi. But Katchor’s light touch, mastery of the monotone scale, and pawky, erudite humor are very different: S.J. Perelman in the funny papers.

Though architecture forms one of Katchor’s central themes, his buildings, like many of those in Golden Age comics, are sketched, not drawn in detail. Prominent but generalized features identify their functions—even in the case of the two identical Art Deco towers in his opera The Carbon Copy Building, one preserved and inhabited by high-end publishers, the other degraded and filled with eccentric bargain outlets. But his characters have sharply individual faces. A bricoleur of genius, Katchor works—as he emphasizes in the documentary film about him that forms part of the exhibition—from things he has seen and heard in the street or bought in junkshops and bargain book racks. Among the Haldeman-Julius Little Blue Books, German Haggadas, colored matchbooks, and other found objects in the cases exhibited at the Jewish Museum appears a lexicon of the Yiddish Theatre, published by the Union of Hebrew Actors in 1931. Katchor’s sketches show that many of his characters began there, as visages trouvés—though others, like the mad businessmen and dramatists of The Jew of New York, have the jagged features of classic comic strip villains.

Anyone who remembers the New York of earlier decades—even the Sixties—will feel a shock of recognition when looking at Katchor’s city. His strips, moreover, teach us to see with new eyes the fragments of an older New York that nestle dusty and untouched on side streets. Yet the nameless city through which Mr. Knipl wanders corresponds not to some particular layer of New York’s historical past but to the multiple layers of Katchor’s own sensibility. That, in turn, has extended itself, in recent years, back to a visionary New York of the early nineteenth century, even more plastered with words than Mr. Knipl’s modern city. This forms part of the background to a story inspired by Mordecai Noah’s abortive effort to create a state for the Jews near Buffalo, New York. The Jew of New York unrolls a sprawling set of interlocking tales about the dreamers and con men who built the canals and shipping lines of the early republic, spinning equally weird fantasies about the Israelite origin of the American Indians and the commercial possibilities of seltzer. Katchor has also moved forward to the present, as Mr. Knipl’s oblique observations on the pleasures of urban decay have turned into more direct, and mordant, comments on the transformation of Manhattan in the boom of the Nineties and the larger economic and social systems in which the changing city is embedded.

Advertisement

Like The Wizard of Oz, the exhibition blossoms finally into color, which is by no means reassuring. Katchor’s recent strips include colorful single-page evocations of the city we may soon have (or that may already be here)—for example, the vision of a Post-Industrial Labor Day parade that he contributed not long ago to The New York Times Magazine. Here the Brotherhood of Espresso Bar Workers, the Cream Cheese Schmeerers’ Association, and the Human Resource Fitters Union march, “on the first dismal Monday in September,” down “the Bowery: the city’s once-thriving Skid Row.” In more recent black-and- white graphic novels, Katchor has also come closer to the present. He has anatomized the role of farming in the modern system of food production, interpreted the paradoxes of postmodern tourism, and extended his critique of the culture of gentrification—most effectively, perhaps in a Swiftian proposal to allow old buildings simply to die.

Born in 1951 and brought up in a world of Yiddish-speaking idealists, Katchor returns, again and again, to the worlds of his childhood in the 1950s. His father, at one time, ran a farm and Communist Party hotel in Saratoga, New York, and at another tried to make his small apartment building in Brooklyn into a commune. Yiddish permeates Katchor’s work, often comically: Knipl, the name of his main character, is the Yiddish word for a nest egg. Moyel—the name of his vanished clothiers—is the term for someone qualified to perform circumcisions. Even more prominent—at a time when food has become our marker for class—are the indigestible dishes, Jewish and American, of another age. In one strip Mr. Knipl races toward a brightly lit delicatessen, desperate for a brisket of beef sandwich and a good sour tomato. Seasoned reader of urban signs that he is, he realizes that the shop’s lights are burning only to allow the floor to be washed, and hurries off in search of meat loaf at a late-night cafeteria. The flavors—of words and foods alike—point unmistakably to New York at mid-century. So do the monologues of many of Katchor’s characters—lost pipe dreamers, who imagine that they can save the world or become rich—or, sometimes, achieve both ends at once, by carbonating Lake Erie or just by creating a new kind of pizzeria. Mr. Knipl’s New York and its successors record Mr. Katchor’s years of doomed effort to go home again.

Katchor comes as the latest in the long series of New York writers and artists who have tried to capture and preserve those layers of history and experience that rapid, continual growth seems to efface. Novelists like W.D. Howells, writers like Thomas Wolfe and Irwin Shaw, photographers like Jacob Riis and Berenice Abbott, collectors like Isaac Newton Phelps Stokes, reporters like Joseph Mitchell, poets like Frank O’Hara and James Merrill have all charted New York’s feverish bouts of creation and destruction. Some of them saved in their words or images the ancient wooden houses, built before the days of tenements, that still stood a century later. Others have preserved the voices of peddlers, oystermen, Mohawk high steel workers, and petty con men who plied their strange crafts in defiance of mass production and the threat of homogenization. They mourned the transformation of a great tavern, where editors danced on the bar, making strange noises and tipping over beers, into a dull, respectable, upscale restaurant. They captured the feel and look of ordinary streets, on ordinary days—the day, for example, when Billie Holiday died. Generation after generation, they have shown us that no one—not even Robert Moses—can eradicate the marks of time.2

In 1951, the year Ben Katchor was born, Alfred Kazin published A Walker in the City. Looking back two generations, to the far-off Brooklyn of his childhood, he remembered the language and the tastes of an immigrant society that was already part of the past. Food gave Kazin’s personal history texture and flavor: the peddlers crying out “Arbes! Arbes!” as they hawked their chickpeas, the candy stores full of gumdrops, polly seeds, and chocolate-covered cherries. Indigestion as the key to a culture: “In the swelling and thickening of a boy’s body was the poor family’s earliest success.” The sweep of great bridges, the grime of tenement stairs, the rattle of elevated trains provided a setting that Mr. Knipl would recognize at once.

Something of what Kazin described in the taut modernist prose of his generation, the visionary language of urban life experienced by wanderers caught between past and future as fragments of sight, smell, and sound, Katchor has evoked in the graphic novels that are emblems of his generation. In recent years, these have proved to be among the most vivid and effective records of, and glosses on, modern life—even in its most terrible moments. No genre seems more appropriate to the modern exemplary city. The newest—and certainly not the last—poet of New York in metamorphosis, Katchor searches for what has been lost and listens with endless alertness for the signs that not everything is lost.

Ben Katchor always knew that history did not stop, even for New Yorkers in the city’s postindustrial age of fool’s gold. In these bad days—especially in these bad days—his vision of New York’s forms, spaces, lights, and shadows offers something vital—a sense of the city’s humanity, as easily lost in boom times as in disaster. Somewhere, Mr. Knipl, once a dance instructor and still a fast walker, strides southward through the city, mumbling to himself about his latest assignment, noting the little businesses in lofts he passes along the way. He examines closed buildings and watches the construction workers clearing rubble. Close to Ground Zero, he sets up his tripod, waits for the sun to reach the right point, and captures, unforgettably, the terrible simplicities that face us now and the complex old energies that they cannot destroy.

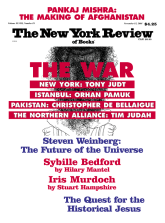

This Issue

November 15, 2001

-

1

The richest account of Katchor’s work—and the one to which I, like so many others, owe my first acquaintance with it—is Lawrence Weschler’s 1993 New Yorker profile, now available as “Katchor’s Knipl, Knipl’s Katchor,” in A Wanderer in the Perfect City: Selected Passion Pieces (Hungry Mind Press, 1998), pp. 223–246.

↩ -

2

See Max Page, The Creative Destruction of Manhattan, 1900–1940 (University of Chicago Press, 1999).

↩