1.

Once upon a time, in a town far away, there lived a boy named Kwame, his sister, Ama, their mother and father, a nanny called Yaa, a cook called Yaro, and two cats who were much too wild to have names and who came and went as they pleased. Every evening, after Yaro had made them a delicious supper, Yaa would help the little boy and his sister to bathe and brush their teeth. Then, on some special evenings, after the children had said good night to the cats, they settled at their father’s feet in the drawing room and waited for him to tell them a story.

When he began with the magical words “Ananse says”—Kwaku Ananse being the name of a very mischievous spider—the children knew he was going to tell them one of the tales his granny had told him, when he was a little boy in the same town, many years before. Because that was how the stories began, they were called “Ananse stories.” And when their father said those magical words, the children knew they had to reply “se sé, se soåø,” the nonsense words that people always said when someone began to tell an Ananse story. The children knew that just because a story was told by Kwaku Ananse, it didn’t have to be about that spider and his tricks. But they were happy when it was.

The children’s mother came from a different, faraway country—and how their parents met is another story, a very romantic one—and so the tales she heard as a girl were different stories. Her stories were not about Kwaku Ananse and his friends and foes, but about Little Red Riding Hood, and Rumpelstiltskin, and Sleeping Beauty, and they came in beautiful illustrated books where dwarves and giants and peasants and princes and talking wolves and calculating cats lived in magic kingdoms and enchanted forests. Often, she listened to Daddy’s stories with the same excitement as Kwame and Ama did, and she grew to like them so much that she thought she would retell them in books of her own; which is why, when Kwame grew up, he could read stories to his nephews and nieces from a book by their grandmother called Tales of an Ashanti Father.

Of course, this is not exactly how it happened. But when my sister Ama and I grew up in Asante with a Ghanaian father and an English mother, we learned the Ananse stories from all sorts of people, including our father; and our mother did publish a series of retellings of Ananse stories for children in England and the United States. Not that my mother was the first to publish Ananse stories: Captain R.S. Rattray, the British government anthropologist who wrote the first extended accounts of Asante history, arts, laws, and customs, issued a collection of tales in 1930; and Harold Courlander, the great American amateur folklorist of Africa and its diaspora, produced, with a Ghanaian colleague, a volume of Tales from the Gold Coast in 1957, the very year that the Gold Coast ceased to exist and we became citizens of Ghana.1 So by these many routes, Ananse joined Aesop’s fables and Grimm’s fairy tales and Charles Perrault’s Mother Goose tales, and a host of other folk tales from around the world.

Ananse arrived from Ghana to find a place on the bookshelves of the New World in the 1950s and 1960s not only by way of collections like Harold Courlander’s and my mother’s, but also in the form of Jamaican “Anancy stories,” whose name must have come with slaves from our part of the world more than two centuries ago. (The gothic novelist and plantation owner Matthew “Monk” Lewis refers to them in the journal he kept when he was in Jamaica in 1815–1817.2 ) Anancy in Jamaica is not simply our Ananse, however. For one thing one of his main antagonists is a tiger, a creature that, in both Ghana and Jamaica, exists only in zoos; for another, he goes to cricket matches.3 So new stories have developed in the new circumstances of a new world; and the old stories have changed and borrowed from other traditions on their transatlantic journey, just as many folk tales have crisscrossed Europe and Asia in millennial peregrinations. Stories recorded in the Panchatantra—which was compiled in Sanskrit sometime before 500 AD for the edification of princes—are said to have found their way into both Welsh and Chinese folk tales (in the former case by way of Arabic).4

We know (for example, from Aesop and from the Chinese Book of Mountains and Seas, or Shanhaijing, probably composed by the second century BC) that tales much like these have been told to children and have entertained adults for thousands of years. And the stories have a universality that allows them to be classified cross-culturally according to their narrative elements, as in Vladimir Propp’s Morphology of the Folktale, which identifies, for example, the different plot elements common to fairy tales (the hero leaves home, the hero and the villain join in direct combat, etc.). They are also classified according to their subject matter (e.g., animal by day, man by night; or girl in service of witch), as in the extensive index of motifs compiled by the Finnish scholar Antti Aarne and translated and expanded by another folklore expert, Stith Thompson; not always, it should be admitted, to the satisfaction of other students of the genre.5

Advertisement

Many of the tales deal with central questions of social and family life, particularly situations of envy, betrayal, reckless ambition, and crime and punishment. In many traditions (including the Ananse stories) the tales teach a lesson that has its own separate life as a proverb or expression, whose meaning is accessible even to those who do not know the story. (From Aesop we have kept, for example, “Sour grapes.”) These expressions reflect the way such stories enmesh people in a single society by transmitting shared pictures of how the world is or ought to be. It shouldn’t be surprising that the common problems of humanity take common narrative forms in different parts of the world.

Still, it can be an uncanny experience to travel halfway around the world to discover a tale you thought you already knew. Among the stories in Nelson Mandela’s delightful collection of his favorite African folk tales is “Natiki,” which comes from a storyteller in Namaqualand in southern Africa, and concerns a beautiful young woman with two ugly sisters who is kept busy with chores by her mother; arrives late, as a result, at a dance (dressed so entrancingly that not even her mother and sisters recognize her); and captures the heart of a young hunter. Should we conclude that the envy of sisters is a universal theme, or that somebody took the Cinderella story from Europe to the Cape, or that the tale is so old that it might, for all we know, have come to Europe millennia ago out of Africa?

Of course, we might be persuaded by W.W. Newell, founder of the Folk Lore Society of America, who argued in 1895 that Cinderella is

an adaptation of a familiar mediaeval novel; starting, as it would seem, less than four centuries ago, from central Europe, this märchen [fairy tale] has been received with enthusiasm equally by the blacks of Angola and by the Indians of America.6

Who can say for certain? As Stith Thompson once said:

Though I have concerned myself for half a lifetime with the history of narrative motifs, I am very skeptical of any success in working out what we may call the prehistory of a particular tale or myth.7

That folklorists have so much material to analyze and compare—the Aarne-Thompson motif-index runs to six hefty volumes—is itself the result of a significant historical development. By definition, folk tales are, in the first instance, stories told by ordinary folk, transmitted orally, and conceived as a common possession. We do not identify them as stories composed by particular authors, even if a moment’s reflection suggests that, if we are passing a story on, it must once have been told in some form by somebody for the first time. But if they are a common possession, by whom, exactly, are they commonly possessed?

The first major collectors of European folk tales had a very clear answer to this question: they belonged to a people, a nation, a Volk. And that answer is one we can trace back to the German Romantic philosopher Johann Gottfried von Herder. Herder had taught in his Reflections on the Philosophy of the History of Mankind (1784–1791) that

every nation is one people, having its own national form, as well as its own language: the climate, it is true, stamps on each its mark, or spreads over it a slight veil, but not sufficient to destroy the original national character.8

A nation—what Herder called a Volk—was fundamentally a cultural unit, not a political one (though it was no doubt natural for people who shared a national character to want to live together in a single state). The real character of a nation was expressed above all in the stories and songs of ordinary people, which displayed its distinctive genius in the spirit of their language. To understand a nation’s character one needed therefore to collect and to study the everyday words and wisdom of ordinary people. Even the literary work of individual writers depended on this oral reserve of literary genius: you could only achieve greatness if you were fully in touch with the spirit of your own language.

Advertisement

As intellectuals around Europe absorbed and amplified these ideas, Herder’s account drew them in two directions: first, toward assembling and recording the oral traditions of ordinary people; and second, toward a greater identification with those with whom they shared these traditions, helping to move them finally from cultural to political nationalism. Since what kept the traditions oral was the fact that ordinary folk didn’t read much, Herder’s picture also raised the cultural standing of unlettered people and thus had, at least potentially, a democratizing effect on notions of civilization.

The search for tales and songs of the ordinary folk as the expression of a nation’s spiritual character was soon being pursued everywhere. Walter Scott’s first work, Minstrelsy of the Scottish Border, published in several editions beginning in 1802, reflected not only the ballads sung to him by his grandmother and a favorite aunt, but those he collected from ordinary balladeers as he traveled around Selkirkshire as its sheriff depute (or chief judge); and he wrote in the preface that the book was intended to “contribute somewhat to the history of my native country; the peculiar features of whose manners and character are daily melting and dissolving into those of her sister and ally” (which meant, of course, England). The oral traditions of the folk defined the national character.

To be sure, folk tales and folk songs had been collected before Herder offered a philosophical reason for collecting them. Giambattista Basile’s Story of Stories (which came to be known as the Pentamerone and contains the earliest printed version of the Cinderella narrative) was published posthumously in Neapolitan dialect in 1634, and Charles Perrault published Stories or Tales from Times Past, with Morals: Tales of Mother Goose in 1697, nearly half a century before Herder was born. The Harvard scholar Jan Ziolkowski has even found what seems to be a version of “Little Red Riding Hood” incorporated in an eleventh-century Latin poem by Egbert of Liège. But in each of these cases the reasons for writing down oral folk tales had nothing to do with Herder’s interest in the national spirit. According to Professor Ziolkowski, Egbert said he drew on oral tradition because it provided students with a familiar starting point, allowing them to experience anew in Latin script a tale they had already experienced in its oral form.9 Basile and Perrault did not discuss their oral antecedents at all.

It fell, in the end, to the brothers Jacob Ludwig and Wilhelm Carl Grimm to begin collecting folk tales for properly Herderian reasons. The first volume of their Kinder- und Hausmärchen was published in 1812, after more than a decade of hearing “children’s and household tales” from ordinary folk (largely in Hesse, where they lived at the time).10 For Herder, nations were ancient and the origin of their tales was lost. When Heinrich Heine described the story of the Lorelei as “ein Märchen aus alten Zeiten,” a tale from the old times, he was expressing, as someone who was born around the time the Grimms began their work, the common conception of these tales. No one thought of old Frau Viehmann, the tailor’s wife from whom the Grimms got so many of their best stories, as anything other than a very able transmitter of “Märchen aus alten Zeiten.”

Sometimes the arrival of a word—and its immediate adoption—reflects a change in intellectual climate. In 1846, William John Thoms, an English antiquary, began a regular column in the Athenaeum. In it he published country yarns, ballads, sayings, and the like, for which he devised the term “Folk-Lore.”11 And, in good Herderian spirit, folklorists, as the students of folklore soon came to be called, took up the idea that every nation was bound to have a folklore. Perhaps surprisingly, the first volume of the Memoirs of the American Folk-Lore Society was a volume called Folk-Tales of Angola.12 Reverend Heli Chatelain, the missionary and linguist who had collected these stories, referred in his introduction to the “unwritten, oral literature, that is…their folklore.”13

For the peoples of sub-Saharan Africa—“tribes,” the English called them, but Herder had been clear that they were, like the Germans, Völker —the collection of their folklore reflected a new situation. For people without writing who had been conquered and colonized by people with writing, it was a plausible theory that the military superiority of Europeans was connected not only with their command of modern armaments but also with the secrets hidden in their books. To work with these new poli-tical masters, one had to learn their language—and that meant not just speaking but reading and, finally, writing it. Writing acquired a substantial prestige, especially as Christian missionaries taught the power of the written Word of God.

In these circumstances, possessing a strong modern cultural identity of one’s own depended more and more on expressing one’s traditions in writing. The collection and transcription of folklore by anthropologists was often welcomed by the indigenous people themselves as giving status in the new cultural and political climate to the oral traditions of the folk. There was much resistance to handing over some of the oral lore, however; the secret knowledge of cures was the basis of the authority of healers, and they did not want to give it away. And family histories are a private matter, not least because the knowledge of the secrets of a family can give power to witches. Collections of African proverbs and folk tales published by local collectors can be found in chapbooks printed over the last century or so throughout the continent. And when people in Ghana or Namibia or Kenya discover that their folk tales—the stories that they think of as particularly theirs—are circulated and appreciated elsewhere, they often take the kind of pride in their own people and traditions that is at the heart of cultural nationalism.

But first they were entertainment. In 1940 in the Journal of the Royal African Society, Edwin W. Smith genially described the home setting of many African tales:

When the cool of the evening succeeds the heat of the day, work is over, and the principal meal is consumed, the time arrives for recreation. They dance long hours, or they gather around the fires for amusement of, shall we say? a literary character…. Who that has experienced it can forget the charm of that witching hour—the flickering firelight illuminating the eager faces….14

For the citizens of the industrialized world whose faces are illuminated by the flicker of television screens, there may be something familiar and enviable about this image of sociable interaction.

What’s also clear from any account of oral narration as it once was practiced is that something is lost when the plot and characters of the often told tale are crystallized into a written version. Because those who first collected folk tales thought of them as a common possession, they often didn’t take much notice of the people who told them; and because the collectors were often missionaries or other respectable middle-class people, they felt free to clean up the versions they collected. The Grimms—though far less cautious than most of their successors—further sanitized and stylized the tales in each new edition of their collection; in the 1819 edition, they assure us that they have removed “every expression inappropriate for children.” (An unsalvageably inappropriate story like “How Children Played Butcher with Each Other” was simply removed.) Such minor emendations aside, though, the Grimms generally thought of the narratives they presented as being timeless and autochthonous. Of their Frau Viehmann, they wrote,

Anyone believing that traditional materials are easily falsified and carelessly preserved, and hence cannot survive over a long period, should hear how close she always keeps to her story and how zealous she is for its accuracy; never does she alter any part in repetition, and she corrects a mistake herself, immediately she notices it.15

Folklorists now conceive folk tales quite differently, recording thousands of variants of stories, noting with scientific rigor the person and the place of collection. They speak of individual “performances” of folk tales—i.e., the particular instances of their being told. Their language suggests that there is a cultural template and that each narrator is presenting his or her interpretation of it, just as each performance of a musical work (especially in the more improvisational traditions like jazz) is an interpretation of an original musical idea. But there is, in fact, no single template, no canonical, abstract version, with its ideal plot and its fixed characters for the tale-teller to interpret. In a literary tradition, we can often talk about a play’s original text, of which each performance is an interpretation. By contrast, an oral tradition depends on a chain of transmission, not a common source; the source, even if there is one, is connected to present performances only through other earlier performances.16

There are, as a result, two very different ways of thinking about what happens when a folk tale is written down. According to the first, the written version is just another performance, though one translated to a new medium with its own aesthetic principles, its distinctive limitations and advantages. Quite different is what we might call the Herderian view—that collecting a folk tale is an attempt to capture what is common to all the performances of it. On the Herderian view, a folk tale is always something that existed before the act of writing. You cannot compose a folk tale in writing; all you do is make an (acknowledged or unacknowledged) ersatz version of the real thing.

By contrast, for people who emphasize performance, it is natural to see the composition of folk tales in writing as continuing, in a new medium, an old practice. For in this view the oral performances were always individual creative acts, drawing on old stories, local circumstances, and the performer’s imagination; and if they expressed a national character, it was not in Herder’s sense of a Volk, but only to the extent that anything anyone does reflects, to some degree, the influence of their traditions and social setting. And once one sees written folk stories as performance, they easily float free of their national origin.

2.

It is fascinating to watch these two conceptions of folklore jostle and collide in Nelson Mandela’s Favorite African Folktales. Each story is brilliantly illustrated by a different artist, whose name appears prominently beneath the title, reflecting the balance of text and illustration that is now part of the tradition of children’s picture books. The illustrations are remarkably diverse, varying both in their degree of abstraction and in the extent to which they incorporate recognizable African motifs, such as the rock paintings by the San people, or Bushmen, of South Africa that inspired Nikolaas de Kat’s illustration for the story of Natiki; and yet they work extremely well together. No one need fuss about whether these visual artists have borrowed or escaped from various völkisch traditions. But beneath the title of each story there is also a brief characterization of the story’s origins, showing the varied routes by which the written words reached Mandela’s eye. And when it comes to the verbal arts, there is a veritable culture war beneath the surface of these seemingly placid descriptions.

We begin, for example, with a Tanzanian story, “The Enchanting Song of the Magical Bird,” which we are told was “recorded at the beginning of the twentieth century in Benaland, Tanganyika (now Tanzania), by Pastor Julius Oelke of the Berlin Mission Church.” Oelke’s publishers didn’t specify who told him the story or claim for the missionary any creative part in the composition of this tale, which is about a thieving bird whose beautiful song has the adults of a small village under a spell, making them powerless to stop the creature from stealing their food. Only the youngest villagers can resist the bird’s magic and they kill it. “Children hear truly and their eyes are clear,” reads the lively English of the translator, Darrel Bristow-Bovey. “The hardened older men and the strong young men could not believe what the children with their thin arms had accomplished!” We’re not informed whether Bristow-Bovey translated from the Afrikaans version, published in South Africa, or a version in Pastor Oelke’s native German. (There is no indication that he is fluent in the Bena language, Kibena.) At any rate, one might assume that we have here a story drawn from a variety of performances in Kibena at which Pastor Oelke was present, transmitted by way of German through Afrikaans to the English of Mr. Bristow-Bovey (who turns out to be the author of an award-winning South African parody of self-help books called I Moved Your Cheese).

According to Herder, none of these disparate filters of transcription and translation should affect the basic authenticity of the story as we have it, or its capacity to express the Bena character. The Herderian approach explains, too, why “The Cat Who Came Indoors” can be introduced simply as a Shona story, “told to [a] folklorist… in the Karanga tongue” (a major dialect of Shona); and why the Moroccan tale “The Clever Snake Charmer” is given no history of collection at all, although we gather from the names of the characters that we are in North Africa. This story is about a capricious sultan who has his entertainers and musicians—his fiddler Mohammed, his harp player Joseph—beheaded when he tires of them. It looks as if the clever snake charmer Selham is going to meet the same end, but he saves his life by answering the sultan’s riddles. (“How many hairs are there in my beard?” asks the sultan. Selham replies, “Just as many as on the tail of my donkey. Cut off your beard and I will cut off my donkey’s tail. Then we can count together.”) We learn that a certain Margaret Auerbach translated this story from the Afrikaans, but there’s no information about how it got into Afrikaans from Moroccan Arabic, or where in Morocco it might have come from.

There are, however, many more stories whose introductions suggest a view of folk tales as performances. These introductions stress the particular origins of the texts we have—who told them to the person who recorded them. “The Snake Chief,” a tale about a woman who thoughtlessly trades her daughter to a snake in exchange for a basket of berries, was “told to” Diana Pitcher “by Miriam Majola, a wonderful storyteller” in Zululand. “The Message,” a story that comes from the Nama people of Namibia, is “retold here by poet, novelist, and short-story writer George Weideman, who heard it from Grandma Rachel Eises.” Aptly enough, the folk tale itself is about the difficulty of transmitting a story. In it, the moon wants to reassure human beings that “just as I die and come alive again, so you also shall die and live again.” She gives the message to a tick, who tries several times to hitch a ride on a goat to the kraal, the compound where people live. But the nearsighted tick jumps onto the wrong animals and ends up far away from the kraal. He finally asks a hare to take him, but the careless hare accidentally dislodges the tick and garbles the message, telling people that the moon said, “Just as I die, and remain dead, so shall you die and perish.”

The nineteenth-century folklorists were deeply concerned to distinguish between Kunstmärchen and Volksmärchen—between mere literary confections and the folk tales they ostensibly decanted from the collective cultural consciousness. (This set them up for some scrutiny later on. Was the sixteenth-century Venetian scribe Zoan Francesco Straparola merely a compiler of fairy tales like “Puss in Boots,” or was he—as Ruth B. Bottigheimer has recently argued—more of a creator?17 ) To his credit, Mandela isn’t much troubled about the distinction. His collection includes newly invented stories in the folk-tale idiom, sometimes drawing on characters in a particular tradition. “The Mantis and the Moon,” by the novelist Marguerite Poland, is about a praying mantis who tries to catch the moon because “he wished to sit on it and cross the sky each night.” In San cosmology, the mantis is an important trickster god called Kaggen. In Poland’s tale, however, the mantis is a more humble figure. After trying to grab the moon from the top of a tree, then to pounce on its reflection in a pond, the frustrated mantis

took a rock and hurled it, cursing the moon.

The stone shattered the reflection and a thousand splinters of moonlight pierced the mantis’s eyes. Blind with pain, he ran away and hid in a thorn-tree.

The story ends with the mantis begging the moon to give back his sight—in his now familiar pose of supplication: “He held out his front legs to it, folded up because he was praying.”

Mandela also includes a story, by the “children’s book specialist” Jay Heale, which, though set in Africa, is related to no particular African-language tradition at all. It’s about a nameless ruler, “the most powerful king in Africa,” who has a magic ring “made of gold brought up the River Nile, inlaid with silver brought up the River Congo, and topped with diamonds brought up the River Zambezi.” As we would expect from many other folk tales, the ring is stolen and it takes the efforts of a magician to get it back.

Mandela ignores the temptations of a “folkish” Africa in another way: the stories here include “Malay-Indian” tales from Cape Town, like the one about Ali, a young man who, while seeking shelter at a mosque, spends his last five hundred coins to save a corpse from grave robbers and is rewarded by the dead man’s spirit. The story’s turbaned sultans could have come from the Arabian Nights. And there is a wonderful Boer story, “Van Hunks and the Devil,” which, in good folk-tale fashion, explains why Table Mountain, above Cape Town, is so often covered in clouds—the result of a pipe-smoking competition between the devil and a reclusive Dutch sailor called Van Hunks (as yet there is no winner). These are tales told by people whose ancestors came—as slaves or colonists—to southern Africa from Holland or the Dutch East Indies. We don’t have any hints about their particular characteristics, although Herder, I suppose, would have expected them to express the national character of the Dutch or Malay and wondered what they were doing in a collection of African folk tales. But the collection reflects, as we would expect, the cosmopolitan spirit of Nelson Mandela: these are African stories because the people who tell them are living in Africa now.

As we would also expect, the collection is heavily weighted toward southern Africa. Nelson Mandela’s favorite stories reflect his origins: and though I regret the absence of Kwaku Ananse (who is acknowledged, however, in the introduction to a Nigerian spider-tale), I have the impression that American children are familiar with West African folk tales, so Mandela’s book can be seen, in part, as righting an imbalance. What matters in the end is that these are marvelous stories, well told and elegantly illustrated. Since there is, as Herder already knew, no “African” character (he rejected the idea of racial characters vehemently and explicitly), you will learn nothing of it from this book. But I doubt that it teaches much of the character of the particular Völker the tales come from, either. If we must be grateful to Herder for having inspired the great nineteenth-century binge of folk-tale collecting, we should feel free to follow Nelson Mandela’s lead in abandoning the Romantic philosopher’s conception of the folk tale as the expression and possession of a single Volk.

In the fairy-tale version of my childhood with which I began, my father’s stories were told to the children and only overheard by my mother. But, of course, African folk tales are told for an audience of all ages: they are not children’s tales or even household tales but community tales. And my fairy tale, like the bowdlerized versions we so often tell to children, also left out much of the darkness and danger of real life, which the older folk tales seldom forgot. In fact, when I was seven the bedtime stories stopped; my father was whisked away to join the growing ranks of political prisoners in Nkrumah’s Ghana. When he came back—no charge, no hearings, no explanation for his incarceration, none for his release—he had acquired a new stock of tales, learned from his fellow prisoners, who had shared their stories to relieve the boredom of a sentence without a trial and, thus, without a definite term. Like Nelson Mandela, Africa’s most famous political prisoner for a generation, my father and his colleagues survived in prison by teaching and learning from one another. So the stories my younger sisters, Adwoa and Abena (born when he was a prisoner), heard when they were little children came from a richer stock. And it was from this enlarged repertory that my mother must have taken her Tales of an Ashanti Father, for she published them in the late Sixties, when Nkrumah was gone.

Creating her version of the Ananse stories for other people’s children—so that they lived on the page, as my father’s had lived in his spirited performances—made her a writer. Soon she was writing novels for children and then for adults. In our world, story-telling (like so many other arts that were once practiced by everyone) has become a speciality; which is why the rest of us need books to read to our children. But there is a recompense for the losses of the transition from orality to writing. For the treasury of tales we can read draws on a thousand traditions and would exhaust a hundred lifetimes. Nelson Mandela’s favorite stories from Namaqualand and Kibena have become the common property of us all. Ananse’s web may yet come to ensnare the world.

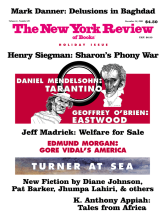

This Issue

December 18, 2003

-

1

Akan-Ashanti Folk-tales, collected and translated by Capt. R.S. Rattray, and illustrated by Africans of the Gold Coast Colony (Oxford University Press, 1930); The Hat-shaking Dance, and Other Tales from Ghana, by Harold Courlander, with Albert Kofi Prempeh, and illustrated by Enrico Arno (Harcourt, Brace, 1957).

↩ -

2

Matthew Lewis, Journal of a West India Proprietor: Kept During a Residence in the Island of Jamaica, edited by Judith Terry (Oxford University Press, 1999). A Selection of Anancy Stories was published in Jamaica in 1899 by the pseudonymous Wona (Kingston: Aston W. Gardner).

↩ -

3

See “Anancy and the Cricket Match,” www.jamaicans.com/culture/anansi/anancy_watchderide.htm.

↩ -

4

See Chapter 1 of John Fiske, Myths and Myth-Makers: Old Tales and Superstitions Interpreted by Comparative Mythology (Boston: James R. Osgood and Company, 1873).

↩ -

5

Vladimir Propp, Morphology of the Folktale, translated by Laurence Scott (University of Texas Press, 1968); Stith Thompson, Motif-Index of Folk-Literature: A Classification of Narrative Elements in Folktales, Ballads, Myths, Fables, Mediaeval Romances, Exempla, Fabliaux, Jest-Books, and Local Legends (Indiana University Press, 1932– 1936); Antti Aarne, The Types of the Folk-Tale: A Classification and Bibliography, translated by Stith Thompson (Indiana University Press, 1995).

↩ -

6

W.W. Newell, “Theories of Diffu-sion of Folk-Tales,” The Journal of American Folklore, Vol. 8, No. 28 (January–March 1895), p. 15.

↩ -

7

Stith Thompson, “Myths and Folktales,” Journal of American Folklore, Vol. 68, No. 270 (October–December 1955), p. 486.

↩ -

8

Johann Gottfried von Herder, Reflections on the Philosophy of the History of Mankind, translated by T.O. Churchill, abridged with an introduction by Frank E. Manuel (University of Chicago Press, 1968), p. 7.

↩ -

9

Jan M. Ziolkowski, “A Fairy Tale from before Fairy Tales: Egbert of Liège’s ‘De puella a lupellis servata’ and the Medieval Background of ‘Little Red Riding Hood,’” Speculum, Vol. 67, No. 3. (July 1992), p. 557.

↩ -

10

Since there were Huguenot exiles from Catholic France in Protestant Hesse, however, some of the stories certainly came (at least most recently) from France.

↩ -

11

Patrick Leary, “A Victorian Virtual Community,” Victorian Review, Vol. 25, No. 2 (Winter 2000), pp. 62–79 (www .victorianresearch.org/nandq.html).

↩ -

12

Folk-Tales of Angola: Fifty Tales, with Ki-mbundu Text, Literal English Translation, Introduction, and Notes, collected and edited by Heli Chate-lain (American Folk-Lore Society/ Houghton Mifflin, 1894). Chatelain developed an orthography for Kimbundu and translated the New Testament into it.

↩ -

13

As cited by W.W.N. in “Folk-Tales of Angola,” The Journal of American Folklore, Vol. 7, No. 24 (January– March, 1894), p. 61. (May we guess that W.W.N. is the same W.W. Newell of the “Theories of Diffusion of Folk-Tales”?)

↩ -

14

Edwin W. Smith, “The Function of Folk-Tales,” Journal of the Royal African Society, Vol. 39, No. 154 (January 1940), pp. 64–65, 67.

↩ -

15

As cited by Joseph Campbell in his “Folkloristic Commentary” to The Complete Grimm’s Fairy Tales (Pantheon, 1980).

↩ -

16

As in ballet performance before film and systems of notation like the Laban and Benesh systems.

↩ -

17

Ruth B. Bottigheimer, Fairy Godfather: Straparola, Venice, and the Fairy Tale Tradition (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2002).

↩