Sue Halpern’s remarkable first novel, like many novels, is essentially about education, or that aspect of education called growing up. But the book’s main character must, in effect, grow up all at once, and the story suggests that education happens not because of anything that teachers do but because certain students want, or are willing, or somehow manage to learn, much to everyone’s surprise.

Unfortunately there are few such students anywhere, least of all, perhaps, in places like the one where Halpern locates The Book of Hard Things, rural northern New England, with its woods and mountains, its hard winters and brief summers, its small settlements where people scratch out livings from marginal farm land, cater to vacationers, or carry on public works like repairing roads in summer and plowing them in winter. Halpern herself divides her time between upstate New York and Vermont, not far from the New Hampshire of some of Frost’s best poems, where old roads may lead to houses or even villages that are no longer there. The world she pictures is also more up-to-date than that, not unlike the Maine of some of Stephen King’s less antic and fantastic moods, where large families in small places diligently interbreed, where pickup trucks are the vehicles not of suburban choice but of necessity, and the young dream of escaping to an “outside” they know only from the media. Halpern’s main characters live in a part of town called “Poverty” by those who live elsewhere, and the Bunyanesque touch has its point.

The central figure in The Book of Hard Things is named Thomas Gage, but no one uses his first name; he’s universally called “Cuzzy” because he has a lot of cousins even for a place where nearly everyone is related to everyone else. He has very little more. He’s an only child, his mother is four years dead, and his father, a Baptist lay preacher, has been in a mental hospital since Cuzzy was nine. Cuzzy is newly out of high school, though hardly educated, and homeless since his cousin Hank kicked him out for “disrespecting” Hank’s wife. He has no steady job; home is a sleeping bag on the shore of a lake. He hangs out with local hard cases who, though also uneducated, live comfortably enough at their own level, like his cousin Joey, recently jailed for having sex with his younger sister and his dog and now working in a clown suit at the Nice n Easy convenience store, where he discreetly swipes stuff for himself and his pals.

Joey’s cousin Ram Pullen, a bully who deals drugs and has “a thing for guns,” likes to say that he and his henchmen, the Miller half-brothers (fondly known as “the Sylvanias” because their heads are shaped like lightbulbs), are the northern posse of an L.A. gang, and they’re certainly avid readers of Soldier of Fortune. Then there’s Cuzzy’s slightly older girlfriend, Crystal, with whom he has had a child, named Harrison Ford Gage but known as “Harry” to his doting mom and his guardedly interested dad, whom Crystal thinks of more as the child’s “donor.” Cuzzy hauls an occasional load of gravel for spending money, makes out with Crystal and a newer and younger girl, Amber-Rose, drinks, smokes pot, and plays the lottery, taking no interest in the regular work that might be obtainable around Poverty.

Yet such bleakly authentic details don’t account for the sympathetic interest Halpern invests in Cuzzy. For one thing, he has a Frostian kind of imagination. He knows a lot about birds and trees and weather. He likes to follow the old tracks into the woods to where they peter out entirely, the point where he can conceive of the people who once lived there:

This was where the house had been, where lives were lived. He would imagine those people on that very spot a hundred years earlier—women with thick ankles and plaited hair and sour expressions, and their pock-faced men. It was always the same for Cuzzy. No matter which road he followed in, whether it was hung over by birch or maple, whether he saw hop vines tangled in the branches or neat rows of stone underscoring the tree trunks, it was always the same. The people were long-suffering and tired. And they were ignorant, yet, that the future had no room for them. Nature would reassert itself: the trees would grow back. The experience of those people would be mulched to obscurity.

The difficulty of representing a consciousness like Cuzzy’s is overcome by the quiet eloquence of such a passage. If some of the phrases seem a little beyond his powers, we can trust that the feelings they point to really are not. Halpern does sometimes stumble, as she does a moment before this passage, when she associates Cuzzy with language that could hardly be his own:

Advertisement

All around them the forest was constantly returning to its metabolic set point. Three generations later, and this was what was left to show that people had been here, had made their lives here: a mossy necklace of flat stone, intentionally laid, the occasional slag of rotted cans….

Would Cuzzy understand “metabolic set point”? (I surely don’t.) Might he blush if required to say “mossy necklace” or even “occasional slag” out loud? But Halpern usually finds her way around such embarrassments; as if expecting someone to question, for example, Cuzzy’s reflections on the old problem of whether any real sound is made “if a tree falls in the forest and no one hears it,” she later provides a credible source—Crystal once read about it to him from a quiz in Psychology Today.

The lost world of Poverty is of course aware of another world, where the “people passing through wanting gas” come from, the ones who “always looked different—cleaner and softer, as if they had a higher thread count.” While Cuzzy’s thuggish friends and relations fantasize about guns and gang warfare, Crystal’s dreams point elsewhere. She lives in a trailer park with her French-Canadian grandparents and works as a flagger on a road crew; her reading runs to People, Self, Glamour, Working Mother, and movie magazines. She imagines scoring big in the lottery or a game show and buying a big house for Harry and herself and maybe Cuzzy. She watches movies and TV and Jane Fonda exercise tapes; she envies the glamorous life of her vanished mother who’s now a “dancer” in “a casino bar up north” (she’s in fact a lap dancer).

Driving with Harry up Whisper Notch, where the rich folks’ summer estates are, she notices the autumn colors in the woods but responds to the natural quite differently from the way Cuzzy does:

It was like a color-blind person knowing the traffic light was green: she didn’t honestly think so. The trees depressed her. Once the leaves were gone, they reminded her of dead people reaching out for heaven, hoping God would choose them.

Though her imagination is less interesting than Cuzzy’s, Crystal is not stupid, and she’s often very winning.

But if The Book of Hard Things has firm roots in local detail, it’s the intrusion of two outsiders that gives the novel its occasion and shape. The Reverend Jason Trimble, a fortyish Methodist minister, is a physically slight, earnest man to whom “little came naturally” but whose vocation is strong and humanly responsive. When he takes up his ministry in the town, his interest in good works grows even stronger when he comes upon Cuzzy, a prime candidate for Christian assistance. When he visits Cuzzy’s father, Leo Gage, in the asylum, he’s impressed by Gage’s “wild and stormy” mind despite his delusion that he’s Pontius Pilate. Gage considers “the main dilemma of theology” to be the “hardness” of life, and he’s gathering materials for a book to be called “The Book of Hard Things,” though he intends for Trimble to do the actual writing. Trimble undertakes to persuade Cuzzy to visit Leo, despite the boy’s embittered conviction that the father he admired and loved has betrayed him by losing his mind.

The other outsider is a more elaborate if somewhat less credible figure. Like Cuzzy, Michael Edwards III seems to have disappeared into his nickname, “Tracy,” through a transformation of “III” to “très” (which, he says, means “three”) and from there to “Tracy.” (This seems quite mystifying: without the accent grave “tres” means “three” in Spanish, but with that accent it means “very” in French, and Tracy, well traveled, highly literate, and linguistically sophisticated, would surely know this.) Wherever his name comes from, Tracy seems out of place in Poverty. He’s in his thirties, tall and delicate of features, and a skilled cook; he’s been an English teacher and knows a lot of difficult modern poetry. He drives an enviable Porsche convertible, which was bequeathed to him by a recently dead friend with the Wildean name of Algie Black, an ethnomusicologist and scion of a very rich family of summer people at whose hunting lodge up in Whisper Notch Tracy is now “doing some work.”

Ram Pullen and the other goons taunt him with homophobic innuendoes, and at first it isn’t clear to anyone, including Cuzzy, who’s horrified by the idea but drawn to Tracy nonetheless, that such suspicions are wholly baseless. Tracy’s friendship with Algie was an intense one; like many bright young men in their late teens and twenties, they had discussed and argued about their tastes in the high and popular arts—from Rilke to Billie Holiday—and he has never forgotten, or quite forgiven, the time when Algie almost kissed him. Tracy thinks that he himself sought a love untouched by sexuality, but Algie indeed was gay, and the sorrow and guilt Tracy feels about rejecting him has deepened after his death, evidently from AIDS.

Advertisement

Hearing about Cuzzy from Trimble, and finding him interesting and appealing, Tracy invites the boy to stay for a while at the Larches, nominally to help with cataloging Algie’s voluminous professional and personal papers and to search for his “lost” tree house, a miniature version of the lodge itself built in a tree somewhere in the estate’s 587 acres of forest. On his deathbed Algie made Tracy promise to find the tree house, where Algie himself learned that “the world is bigger than me. I want you to see that,” and Tracy hopes that it can teach Cuzzy the same thing.

The tree house helps to locate the spiritual center of The Book of Hard Things. It recalls Frost’s great poem “Directive,” with its imagined search, like Cuzzy’s, for the lost worlds at the end of old country roads. Frost associates that search with a quest for salvation in “a broken drinking goblet like the Grail,” which you know you’re approaching when you find “the children’s house of make-believe” at the site of the farmhouse that has disappeared into nature. Tracy senses that his own quest constitutes a kind of ritual:

People die over and over again, Tracy thought. Their physical death is just the beginning. Why hadn’t he seen this before: the death of someone you loved was your own involuntary initiation into the kiva of loss, an initiation that ended with your own death. It was the perfect initiation ceremony, and it was universal; he wished he could tell his friend.

Cuzzy finds the tree house, quite by accident, just before the story reaches a harrowing climax. He’s begun to show signs of what Trimble and Tracy had hoped for him. His reclusive, shy—or sly—sense of himself is suggested by his way of wearing his hair long in a “curtain” down to his chin; but when he peers through, his expression often reveals curiosity. Tracy thinks that

Cuzzy was beginning to wake up to the world. His wariness, that of the fox prowling the margins, was still there, but his diffidence lifted now and then like a curtain, parting to show what might have been—if his father hadn’t been taken away; if his father wasn’t sick; if his mother hadn’t died—and what might be there yet.

Though inwardly dismayed by the prospect of his new friend’s leaving to accept a Fulbright in New Zealand, Cuzzy angrily rejects Tracy’s offer to take him along. Part of him remains comfortable enough with the known world of Poverty, where he expects to stay on doing dull, menial work, perhaps cutting meat at Grand Union. (“How hard could that be?”) He resents Tracy’s trying to educate him, but he’s well aware that all the poems and music and anthropology have “worm[ed] their way into [his] brain, and like it or not, he’d have to think about them.”

He has always been taken by the idea of parallel universes:

…In one of them people like himself existed only in shadow, as reflections of people looking in. So he had listened to music from Burkina Faso. So he had absorbed those rhythms. So he had read “The Snow Man.” So he had read “Dry Loaf.” So he had absorbed those rhythms, too. He was going to get a job moving earth. He was going to get a job hauling logs. Some night he was going to be pushing snow from one side of the road to the other, three AM, with the river catching the moon and carrying the light downstream, and the words “Regard now the sloping, mountainous rocks and the river that batters its way over stones” would come into his head like the fortune on a Magic 8-ball. Here was the poem itself, laid out before him. And he would be able to hold it in contempt.

It is at this point that Cuzzy’s education is completed; the large question for him has been whether he can combine as parts of a complex whole the outside culture he’s been learning about and what he already knows. He passes the test by imagining the future, or, more exactly, by imagining himself, in the future, imagining the real river and the river in the poem as in some way equivalent and in some way different, and by understanding that to see the poem critically, to hold it in contempt even briefly, in contrast to the natural scene, is a way of gaining power over the outside world that both frightens and mightily tempts him.

When Tracy mixes the cultures by inviting Cuzzy’s friends to the Larches for a birthday party for him, which is also Tracy’s farewell, the party is fairly successful at first. Even Ram likes the food and the crystal and napery, and it’s some comfort to Cuzzy to reflect that his friends will still be here for him after Tracy leaves. But Ram has brought crystal meth and pot, and as all but the disapproving Tracy get recklessly high, a game of “Truth or Dare” leads to disaster: Cuzzy is forced to drink a bottle of vodka, scuffles with Joey, and passes out. The others tie Tracy to a chair, gag him with duct tape, and make him the target of “Ring Around the Pansy,” their version of horseshoes, which kills him. In effect, Cuzzy’s “family,” all the community he has, seeks to keep him for itself by destroying the source of his temptation to reject his own kind.

Cuzzy’s idea of dual universes suggests how carefully Halpern has shaped her story. For Tracy, his own death completes the “initiation into the kiva of loss” that began with Algie’s death, a completion that’s both awful and somehow right. For Cuzzy it leads to something quite different. When he wakes from his drunken coma to find Tracy dead and disfigured and the others gone off with the Porsche, he rushes out too lightly dressed into an ice storm. Jason Trimble finds him collapsed on the road stricken with hypothermia, takes him to a parishioner’s house, and warms him as best he can, with blankets, a dog, and his own breath and naked body. This inspired blending of the Good Samaritan parable with Cuzzy’s fears of the homoerotic saves his life, though he loses his toes, and Trimble and his wife, a witty and benign nurse, look after him while he recovers.

Tracy’s killing draws national attention to this out-of-the-way corner of the country. Crystal, though a devoted reader of People, breaks the glasses of one of its reporters for too insistently trying to take her picture. (His worst mistake is to say: “You know, if our readers saw how you people up here have to live, maybe something could be done about it.”) Cuzzy’s future remains uncertain as the story draws to its close, but he has moved toward possibilities that Tracy’s end seemingly deprived him of. He reads “The Poem That Took the Place of a Mountain” in the volume of Wallace Stevens’s poems Tracy had given him, and he seems, as Tracy had hoped, to find something of himself in it:

…He breathed its oxygen,

Even when the book lay turned in the dust of his table.

It reminded him how he had needed

A place to go in his own direction,…

The exact rock where his inexactness

Would discover, at last, the view toward which they had edged….

He hopes the prosecutor will let him read this in court when he testifies against Ram and Joey.

As the book concludes, he is driving with Trimble to visit his father in the asylum, and his possible acceptance of stronger kinship is signaled when he stops the car outside Crystal’s grandparents’ house trailer and sees her through the window, nursing Harry as she dances with him in her arms. Though Cuzzy first turns away, he then turns back and knocks at the door. The book, that is, leads Tracy to a kind of martyrdom for love even as it leads Cuzzy toward both an adequate family and a less solitary life. At the least he acquires a surer sense of what he has been and who he perhaps can be.

This, finally, is the point of the novel’s enigmatic title. The “hard things” that Leo Gage takes to be the main problem of theology are not just abstract ideas about the difficulty of godly living but examples of a solid, concrete hardness in the indifference that separates human creatures from one another. Near the beginning, Crystal feels that “the lives around her…were hard as rock…hard like slate—all gray and dull and brittle.” And Leo’s later question, “Why is everyday life so goddamned hard?,” clearly means not only “so difficult” but “so impervious to our understanding and compassion.” The book dwells upon such hardness—from the slate and schist and bedrock of the ungrateful New England landscape, to agate, copper, diamond, ivory, and crystal, what human art uses to create beauty, to “quoits,” which as Halpern carefully points out can be either iron rings thrown in a game or the covering stones on megalithic dolmens, or tombs.

Trimble anticipated the problem even before he met Leo, when he preached a sermon on the Good Samaritan to a congregation that included Tracy. The sermon’s theme is familiar, even trite—Jesus urges us, like the Good Samaritan, to “reach out to people who are different from us,” like Blacks and Asians and Jews. A Good Samaritan, Trimble says, “breaks through the walls that separate us and, by his example, shows us what a neighbor is”; his reward is “eternal life.”

Though Tracy’s terrible death is a kind of parody of Christian martyrdom, there’s no suggestion in this tough-minded book that it brings him “eternal life.” But for Cuzzy it does something like what Algie had hoped the tree house might do for Tracy, show him his place in a larger sense of things. In a book about families in which names and relationships tend to dissolve, Algie Black does not bear the name of the family that owns the Larches; they are called “Shoreham,” and Algie’s father, christened James Blackfoot Shoreham, was the bastard child of Augusta Shoreham by an Indian guide whom (by accident?) she killed (and field-dressed) before disappearing forever. James changed the rest of his name to “Shoreham Blackfoot” and Algie himself changed his family name to “Black,” so that the historical echoes of racial victimization—enslaved African blacks and dispossessed native peoples—overlap. (Frost’s “Directive” also catches the latter implication: “The height of the adventure is the height/Of country where two village cultures faded/Into each other. Both of them are lost.”) And the ironies compound as one reads on: James Blackfoot was obsessed with horseshoes and iron quoits, and the ones that kill Tracy come from his extensive collection. Adequate families, in short, are not inherited but created and confirmed, or destroyed, by the acts of their members.

Halpern’s admirably brief but ambitious, intricate, and beautifully composed novel contains and explores more than a casual reading is likely to apprehend. But it’s first of all an approachable, carefully observed, appalling yet sometimes quite funny story of children and parents growing up, the haves and have-nots of contemporary America both in the north woods and, of course, elsewhere too. Sue Halpern is doing more than tell this story, and what that more consists of will, for a long time, bear reflection.

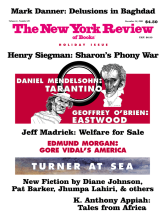

This Issue

December 18, 2003