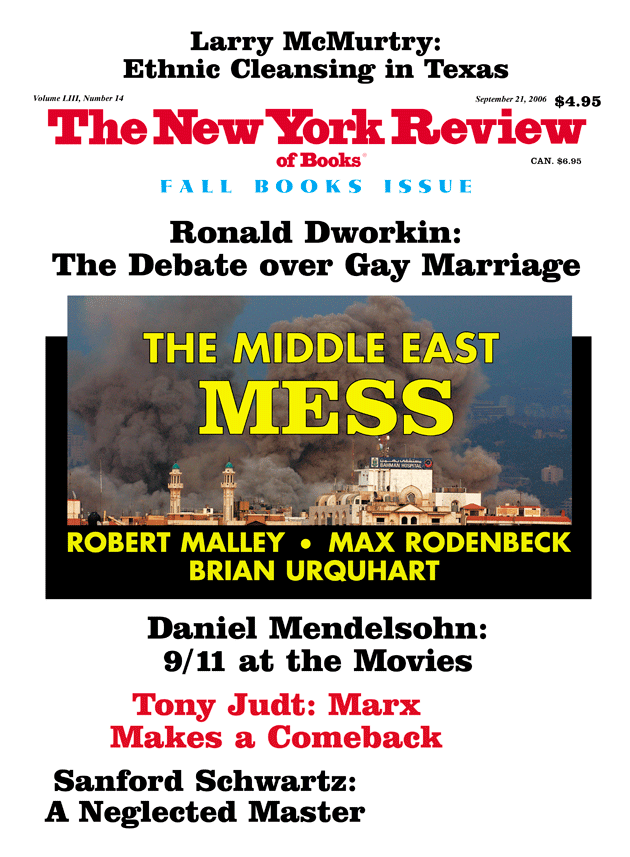

1.

Gary Clayton Anderson, author of this thunderclap of a book, lives in Norman, Oklahoma, which is just a hop, a skip, and a jump from Texas, far too close, I would think, for a scholar who has now suggested that the Texas Rangers—our heroes, our protectors—are pretty much the moral equivalents of certain paramilitary units from the former Yugoslavia—Balkan death squads, in effect. If I had made that comparison I would immediately check out the housing situation in Spitzbergen, where there’s lots of dark to hide in. Certainly I would settle as far as I could get from the Texas Ranger Hall of Fame and Museum, which is in Waco, Texas, a very short distance itself from the famous ranch house where it was once suggested that Laura Bush sweep the porch.

Already Byron A. Johnson, director of the Texas Ranger Hall of Fame and Museum, has come out fuming, in a review that accuses Professor Anderson of being ignorant of a host of disciplines and study areas that he ought not to be ignorant of.* Why is Byron A. Johnson fuming? Probably it’s because The Conquest of Texas: Ethnic Cleansing in the Promised Land, 1820– 1875 is the most intense and persistent attack on the character of nineteenth-century Texans, including the Texas Rangers, that I have ever read. The subtitle is important—I’ll get to it in a minute.

The Texans I know, and I live there, are almost wholly unaccustomed to thinking of themselves—much less their revered forebears—as the bad guys. Aren’t the Dallas Cowboys still America’s team? Aren’t the Mavericks improving? What could be so bad about whatever Great-Great-Grandpa did to those sneaky Indians or those avaricious Mexicans? And aren’t the old histories, books such as T.R. Fehrenbach’s Lone Star, really the best? In the old history Texans were upright and righteous people, and that’s the way it should be.

Most Texans, I think it’s safe to say, have never given a moment’s thought to historical revisionism, of the sort practiced by Patricia Nelson Limerick in The Legacy of Conquest, her revisionist classic. (When I first picked up Gary Anderson’s book I thought his Conquest might harken back to W.H. Prescott’s Conquest of Mexico and Conquest of Peru. Nope. He’s harkening back to Patricia Nelson Limerick’s conquest of triumphalism.) At one point Gary Anderson refers to David E. Stannard, author of American Holocaust, as an “excoriating revisionist”; but if Professor Anderson’s searing critique of the character and behavior of our former heroes, the Texas Rangers, isn’t “excoriating revisionism” I just don’t know what is.

To give the reader some idea of how nearly automatic the resort to violence was on the Texas frontier, here are two short descriptions of Ranger behavior. Both occurred in the spring of 1848. The captain in charge of the first group was Samuel Highsmith, said by those who knew him to be “high-strung.” Captain Highsmith was also spoiling for a fight:

In early April 1848 his scouts reported Indians. They had stumbled onto a hunting party of twenty-six men and boys who had camped to make dinner in a valley well south of the Brazos River. Most of the Wichita and Caddo Indians in the camp had hung up their arms as they lounged about the cooking fire. Highsmith’s troops crept to within one hundred yards and then charged the Indians, firing Colt revolvers at man and boy alike.

The startled Indians had little chance. Some jumped into the nearby stream and were shot in the back. Others reached the bank on the far side and tried to escape up the bluff, making easy targets. When the smoke cleared Highsmith counted twenty-five dead Indians.

Highsmith and his men were hailed as heroes in San Antonio, but, a few days later, a troop led by Lieutenant Thomas Smith

spotted a sixteen-year-old Caddo youth who, [Robert] Neighbors [the officer sent to investigate the event] later reported, “had given no offense—whatever.” Twenty rangers gave chase and shot him down. They fired nearly a dozen times. Five bullets penetrated his body, and two shattered his skull. While poking at the corpse, they discovered that the boy had served them faithfully as a hunter for several months over the past winter.

It’s hard to put much of a shine on the killing of that Caddo boy.

Those are but two incidents from hundreds that illustrate what an extraordinary level of violence was commonplace in early-day Texas. Few on the frontier were ever really safe—housewives, soldiers, merchants, all were attacked. Despite their usefulness, many military men disliked the Rangers. General Zachary Taylor, hero of the northern campaign in the just-finished Mexican war, actually dismissed the Ranger troops at one time but the dismissal didn’t hold. Other attempts were made to get rid of the Rangers, or at least to curb their power, but all such efforts failed. People wanted the Rangers, at least as symbol, and two generations of Texas historians (Walter Prescott Webb, Eugene C. Barker, Rupert N. Richardson, T.R. Fehrenbach, Robert Utley) have written protectively of the Rangers, always downplaying Ranger misbehavior, keeping the symbol untarnished. I took a swipe at the Rangers in a novel called All My Friends Are Going to Be Strangers but then wrote Lonesome Dove. I thought of it as a mythbuster but instead it merely gave the myth new life, and the balloon may rise even higher when a six-hour prequel, Comanche Moon, is aired on CBS next year.

Advertisement

A few tough-minded studies, nearly as critical of the Rangers as Gary Anderson’s, have appeared: Charles H. Harris and Louis R. Sadler’s The Texas Rangers and the Mexican Revolution: The Bloodiest Decade, 1910– 1920is unsparing in its treatment of the Rangers; Gunpowder Justice: A Reassessment of the Texas Rangers by Julian Samora, Joe Bernal, and Albert Pena is also important, since it gives the Chicano point of view.

But when Professor Anderson speaks of the need to demythologize Texas I can only wish him luck. He’ll be lucky if he demythologizes it for a few historians and their graduate students. At this late date demythologizing Texas is beyond anyone’s power.

2.

The above is not meant to suggest that all Texas Rangers were bad, or that their use of violence was more destructive than the violence used by their opponents. The Indians and the Tejanos—people of Mexican descent—were just as violent, just as frequently. A short time after they disposed of the defenders of the Alamo, the victorious Mexican soldiers marched 350 men out of the village of Goliad and shot them down on the road.

As for the Plains Indians—Comanche and Kiowa particularly—a long record of violence speaks for itself. Rachel Plummer, who survived her capture by the Comanches and wrote about it in an important captivity narrative, told her rescuers that she had not been raped—“the fate worse than death” occurred less often than was popularly supposed, at least in some parts of the West; fears about the impurities of white women may have been inhibitory.

Though Rachel Plummer escaped rape, she was pregnant when captured and had the agony, as soon as her baby was delivered, of seeing it dragged to death behind a horse. Mrs. Harris, another captive, saw her three-year-old killed as well. Comanche mothers, who lost one child of three, probably reasoned that these white children had no chance to survive. Any child likely to slow the band down, or give its presence away, was quickly killed.

The imposing Kiowa chief Satanta, while helping to carry out the Warren Wagon Train massacre in 1871, tied an unfortunate teamster to a wagon wheel and cheerfully roasted him; he then rode to nearby Fort Sill, where he bragged to a US Indian agent about the torture, which might have been the appropriate thing to do, in his culture, but led to his being arrested, tried in Jacksboro, and sent to prison, where he committed suicide, after being paroled and then arrested again. It was, on the whole, a rough frontier, and institutions that might have made it more orderly—such as a solid legal system—were slow to develop in Texas.

How, then, does Professor Anderson’s subtitle, Ethnic Cleansing in the Promised Land, 1820–1875, fit with the situation in nineteenth-century Texas? In this case I agree with Byron Johnson of the Texas Ranger Museum that the term “ethnic cleansing” doesn’t fit at all. The former Yugoslavia was not a frontier: Belgrade was not Jacksboro, Texas. The ethnic enmities that existed in the former Yugoslavia were a very old business; Rebecca West’s Black Lamb, Grey Falcon is still the richest study of this long, twisting history.

Ethnic conflict in frontier Texas was, instead, a rapidly evolving struggle between people who hadn’t known one another very long, and, in the main, never came to know one another very well. Indian removal as a policy, however terribly it afflicted the Cherokees, Choctaws, Creeks, and others who were hounded down the Trail of Tears, did not result in extermination. Those Indians, of course, had been settled people; removing them was one thing. But how do you “remove” the Comanches, those nomadic will-o’-the-wisps? Many settlers and most Texas Rangers would probably have preferred that the Indians be exterminated, but for much of this period, the military—regular or irregular—simply didn’t have the muscle to do it.

3.

The Anglo influx into what is now Texas but was then Mexico became serious during the 1820s—some 30,000 Anglos seeped in during that decade—a number about equal to the Indians and the Tejanos, who were already there. The seepage quickly became a flood. By the time Texas became a state, in 1845, about 160,000 Anglos were there; when the Civil War came there were, Professor Anderson claims, 600,000 Anglos in Texas, which seems a lot.

Advertisement

With numbers like that pitted against them it’s surprising that the native people lasted as long as they did. At least a dozen tribes were scattered through the state—Kickapos, northern and southern Comanches, Wichitas, Wacos, Lipan Apaches, Caddos, Coushattas, Karankaways, Tonkawas, and Cherokees. Many of these tribes were small and weak; most of the strength lay with the Comanches and the Cherokees.

Mexico achieved its independence from Spain in 1821, and quickly developed very liberal colonization policies. An Anglo immigrant could receive almost five thousand acres of land, free; but Mexico had also abolished slavery, so who was going to work the five thousand acres? Cotton then was the preferred cash crop, and cotton doesn’t weed or pick itself. Once Texas was free of Mexican rule, slaves began to be brought in in sizable numbers and lots of cotton got weeded and picked.

Professor Anderson regards the Texans’ war for independence as essentially a land grab, which seems a little reductive. No doubt a fair percentage of the world’s many wars are to some extent land grabs, but at least as powerful a reason for the Texas war of independence was that white Anglos didn’t want to be governed by brown people. One of Anderson’s points is that Texans had no tolerance for ethnic diversity. Texas was part of Mexico for fifteen years. Many alliances were formed, and even a state—Coahuila-Texas—but the alliances did not change the fact that two people with very different governmental traditions were headed for a clash.

As the 1820s became the 1830s, with Anglos flowing into Texas in ever-increasing numbers, no less a person than Andrew Jackson, president of the United States, began to give some thought to buying Texas. Jackson shook his old friend Sam Houston out of what Gary Anderson calls “a four-year drunken stupor” and hustled him off to Texas to check out the prospects. For all his drinking, Houston was a shrewd, pragmatic politician. He was also possessed of an almost inexhaustible vitality. When war came he was made commander in chief of the Texas army and soon won the decisive Battle of San Jacinto, capturing Santa Anna, the Mexican leader, in the process. Santa Anna was also practical. He readily agreed to let Texas have its independence.

Sam Houston was twice president of the Republic of Texas, served more than a decade in the US Senate, and then became governor of Texas, from which position he tried in vain to keep Texas from seceding. He refused to pledge allegiance to the Confederacy and was forced out of office as a result.

Professor Anderson doesn’t supply much in the way of biography; his interest is in the broader forces that drive peoples into conflict. He is particularly good on the run-up to the Alamo, when broader forces were complicating the futures of Texans of all races and hues:

As this ever-tightening web of ethnic conflict and intrigue unfolded—as the men at the Alamo faced their martyrdom, as immigrant and Plains Indians considered their choices, as Houston and Santa Anna raced to meet their destinies—the cultural circumstances, the ethnic and racial differences and the personalities that drove Texas history, soon led inevitably to war. Men such as Moore, Burleson, Dimitt, Bowie, and Travis—men of the South who put honor, chivalry, and a belief in the inevitable rightness of Anglo rule above all else—rose to defend Texas. And Santa Anna marched to strike them down. In this increasingly opaque struggle, notions of “loyal” Tejanos and Indians became obscured by the myopia of war. Texans soon became convinced that only their beliefs, though at times prejudicial, hateful, and violent, were glorious and righteous.

4.

War came, the Texans won, but nothing became any less opaque. The conflict with the Plains Indians was to go on for another forty years, with neither side able to gain a clear advantage. In 1840 some poorly informed army leaders decided to trick a number of Comanche headmen—they would lure them in under a flag of peace and then arrest them. This treacherous effort led to the famous Council House fight at San Antonio. Sensing the trap too late, the Indians made a desperate effort to cut their way out. Thirty warriors and five women and children died, an awful toll for the Comanches to absorb, and a huge blot on the trustworthiness of the Texans. Some among them probably thought they had taught the Indians a decisive lesson.

Such optimism faded in the autumn of that year when a Comanche-Kiowa war party numbering at least seven hundred drove straight down through Texas, hit the town of Victoria, and went on to Linnville, a small coastal warehouse village. The Indians helped themselves to long rolls of cloth and accumulated about 1,500 horses, some of which the Rangers managed to recapture as the Indians went back north. They had, in some degree, avenged their dead—very few Texans could see any reason to feel complacent when the Plains tribes could still muster seven hundred men.

If the Council House ambush marked a low ebb for Texas honor, the Linnville raid was one of the last great demonstrations of Comanche power—still, thirty-five long years were to pass before the Comanches ceased to be a threat. A book I used to read and reread was Rupert N. Richardson’s The Comanche Barrier to South Plains Settlement (1933). One reason for my keen interest was that my paternal grandparents were very aware of that barrier when they journeyed to Texas to begin pioneer life. Even after the Comanches were consigned to a reservation in 1875, tales of the Comanche terror were so many and so recent that they held the power to frighten for a full generation after the Comanches had done anything frightening.

The years from 1840 to 1875 were seesaw years. The Anglos were slowly winning but the Indians still conducted many effective raids. During the Civil War years, with the frontier sparsely defended, the Indians won back patches of their former territory. By the late 1850s, Professor Anderson concludes, West Texas was in a state of complete anarchy. So bad was it on the western frontier that many failed to notice that East Texas was becoming more and more stable. There the rule of law could usually be counted on.

One of the strangest aspects of Texas governance in the middle years of the nineteenth century was the government’s incessant and almost wholly futile efforts to establish boundaries within which somebody or other might agree to stay—until they changed their minds. Few of any race really understood these boundaries and no one bothered much about them.

One of the few Comanches who did understand boundaries was the great Penateka Buffalo Hump, who, because of the peace treaty of 1865 between the federal government and the Comanches and Kiowas, at last felt that he had been given the homeland he wanted, near the headwaters of the Brazos, the Red, and the Canadian. But the treaty of 1865, whose first article optimistically pledges that “perpetual space shall be maintained between the people and Government of the United States and the Indians parties hereto,” was the result of war exhaustion. The Texas government, at this point in wild disarray, had no idea that the victorious Yankees were actually giving West Texas land to Indians. The treaty of 1865, like all treaties, soon got watered down.

By 1865 the Plains Indians, northern or southern, knew that something very grim was happening in their hunting grounds: the buffalo were being exterminated. The buffalo was their larder, their commissary. General William Tecumseh Sherman, who favored extermination, saw clearly and early that the advance on the railroad would bring the hunters who would wipe out the buffalo and doom the Indians. He was all for it, but it didn’t work out quite that way because the Indians had large herds of horses and didn’t look askance at horsemeat. They liked buffalo better but horses would do.

All this Gary Clayton Anderson understands and reports. But the unusual thing about his book is its long and persistent critique of violence. Here is his stark conclusion:

Texans never agreed to accept the existence of western Plains Indians in the state under any circumstances. It was this denial, this refusal to accept ethnic diversity—seemingly inevitable under the Southern code—that condemned Texas to a history of violence and instability. Once started, once viewed as heroic and honorable, such violence was difficult to bring under control—it became simply the price of what Texans perceived as “civilization.”

5.

I grew up on what had long been the Comancheria and do not want to leave the field without mentioning two figures who loomed large in that country.

The first is Quanah Parker, the son of the famous white captive Cynthia Ann Parker and the Comanche leader Peta Nocona. While father and son were on a hunting trip the Rangers came, discovered that Cynthia Ann was white, and took her and her young daughter Prarie Flower back to the settlements with them. Both Prarie Flower and Cynthia Ann soon died, the latter of grief. Quanah mourned his mother all his life. His band, called the Qua-ha-das (Antelope), lived deep in the arid Llano Estacado; Quanah kept some few of the Qua-ha-das apart from whites until the spring of 1875. But once he yielded to the inevitable he worked well with the whites and did much to ease the passage of his people into captivity. When Quanah came in to surrender he brought three eagle feathers with him. Recently, in Santa Fe, my partners and I and our filmmaking colleagues were honored with a blessing ceremony in which we were touched by Quanah Parker’s eagle feathers. We had not expected such a blessing; we were much moved, for Quanah was their great man and he was great. For the Comanche people Quanah Parker’s spirit still broods over those long plains.

The other figure who should be remembered was the brilliant young cavalry officer Ranald Slidell Mackenzie, whom the Indians called Bad Hand. The Qua-ha-das Comanches never supposed a white man could go where they could go. Mackenzie proved them wrong. He may not have gone as deep in the Llano Estacado—part of what was once known as the Great American Desert—as Quanah, but he went deep enough. In September of 1874 he followed several Comanche bands into the Palo Duro Canyon. Most of the Indians got away but their horses didn’t. They numbered nearly two thousand—Mackenzie had every one killed. And that was it. The Red River War was over, and so was a way of life.

As his wedding day approached, Ranald Slidell Mackenzie became insane, and he remained insane. There’s your legacy of conquest, Texas.

This Issue

September 21, 2006

-

*

See The Quarterly of the National Association for Outlaw and Lawmen’s History (Summer 2006), pp. 54–57. ↩