A viewer familiar with early- and mid-nineteenth-century American decorative arts, specifically with the painted ornamentation on the furniture, clocks, and china of the time—the squat travelers on their way, the sailboats with their pointy sails, the trees with their one-brushstroke boughs—might do a double take looking at the work of Thomas Chambers. It is as if all the curvy, streamlined, and dexterously executed flourishes on those pre–Civil War wood, fabric, and lusterware domestic items have been captured by, or perhaps stolen by, this British-born, American marine and landscape artist of the time. Whether he paints shipping in Boston harbor, with flags and clouds stretched by the wind, or sloops making their way up the Hudson River on a glistening autumn afternoon, or his subject is the wonder of being face to face with a giant waterfall, Chambers’s work, currently the subject of a rousing exhibition at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, seems at first less like the product of a particular person than an emanation of antebellum American life as a whole.

Adding to one’s initial sense of disorientation when looking at Chambers—who in all probability died in 1869, at sixty-one—is a salient detail associated with his shadowy presence in the annals of American art. The first time he was exhibited was in 1942, in a New York gallery, where, as part of the show’s title, he was called “First American Modern.” At the time, such an appellation was hardly far-fetched. In the early 1940s, modern art, in sculpture as well as painting, could be seen as almost synonymous with boldly simplified forms and with brushwork and intense, bright color that call attention to themselves. In that world, where American nineteenth-century folk painters such as Edward Hicks and Ammi Phillips could seem kin to Miró and Calder, Chambers—whose mountains, ship sails, clouds, waves, sprays of spume from waterfalls, and boulders along the shore have the presence of so many flat yet animate shapes, and give some of his pictures the beauty of arabesques—could certainly strike viewers as having an affinity with Hicks and Phillips, if not exactly as our first “modern.”

If the label stops us in our tracks today, it may be because the connotations of “modern art” are less clear now than they were in the early 1940s, and the description can feel dated as well. Making the acquaintance of Chambers is thus a doubly spooky experience. It is as though in looking at him we are coming in contact primarily with the taste of the 1940s in addition to the taste of the 1840s—a condition set in motion because the artist as a person is a blank to us. After his auspicious debut, Chambers became sought after by serious collectors of folk art; but given that the present show is now only the second he has had and is the first retrospective look at him, he is probably as obscure to the general museumgoing public today as he was in 1942. The catalog accompanying Philadelphia’s exhibition, for instance, is the first book about him.

And while Kathleen A. Foster, who wrote the catalog (and organized the exhibition), has done a tremendous job of research, Chambers remains a considerable mystery. Although most facts concerning him are open to question, he appears to have come from Whitby, a seaport in northern England, and had a brother, George, who was a respected academic marine painter and exhibitor at the Royal Academy. The Chambers brothers were part of a tradition in places like Whitby where there was a built-in audience for paintings of marine life (and where people who weren’t artists by trade could supplement their income by making souvenir pictures or models of individual ships and of the seafaring life). City records show that Thomas arrived in the States in 1832 and lived over the years in New York, Boston, Baltimore, and Albany. He was married, the father of two children, and outlived his wife. He also outlived the market for his work. Perhaps that is why, after the Civil War, he returned to England, where he died in a poorhouse.

But about Chambers’s thoughts and temperament we have only his pictures to go on. Besides items such as notices for auctions that included his work and a slight inscription on the back of a painting, little or no documentation concerning his art or life has turned up. Only a few of his paintings are signed. Like other folk artists (Foster also refers to him as a “popular” artist), Chambers apparently worked for a middle-class clientele that thought of pictures primarily as ornaments for their homes. For them, pictures were neither financial investments nor elements in a larger conversation with their culture. Chambers (and his market) led an existence completely apart from the art world of the era, with its organizations, exhibitions, and reviews. No critic would have thought to write about him.

Advertisement

We are left with a painter who may have chosen, because he saw a ready, paying audience for it, to work in a kind of flat, unillusionistic, decorative style—or who was simply unable to paint or draw, like his brother George in England, in a more “lifelike” or realistic way. Whatever his motivations, Chambers’s sense of space, shape, and color, far from becoming dim or anemic over time, probably seems more robust and delicious today than in his own day. At the very least, his gleaming, Technicolor world will make a few would-be painters among viewers think that maybe they can finally take a stab at it.

With his inflamed coppery skies, distant lavender-touched mountain ranges, parakeet-green waterfalls, countless ways of showing white-capped waves, and dark forests highlighted with patches of orangy-red and ivory-white, Chambers’s pictures can flood your senses with the excitement of carnival color and intuitive brushwork. Mountains loom, pathways dip and rise, clouds dance across the sky, and the sails of his ships billow (or crumble in images of naval warfare) according to, it seems, some impetuous sense of design. Even his largest pictures, which are some four feet wide (most are in the vicinity of two and a half feet wide), have about them the spirit of sketches that have been worked up. We look at bold, clear-cut areas of light and dark, seemingly thrown into place with a rhythmic assurance.

Hardly every Chambers picture, however, is charged in color or has a rhythmic force. In a quarter or so of the forty-five paintings in the show, where we look at scenes purportedly set in “Scotland” or “Mexico,” or at some generic bridge-and-castle motif, he operates merely as a product-maker of a bygone era. Yet there is a certain underlying tension to his art. The few biographical details we have dovetail in tantalizing ways with the most variable and extraordinary aspect of his work, his painting of water. Being a marine painter—showing harbor life, particular ships, naval battles—clearly held the deepest claim on him. City census reports, with their addresses, show that his homes were, unusually, right in the port areas. A few of the marine paintings were the only ones he signed. We can almost think that, in these works with their blithe lack of concern for the niceties of painting—niceties that his brother George obeyed—Thomas was playing out a kind of parable about individual freedom in a new nation.

His paintings of ships in storms, with heaving seas and sails ripped to shreds, form, in any event, images of genuine distress. In his views of battles from the War of 1812—a popular subject in Chambers’s time, with its new muscle-flexing nationalism—he gives damaged sails and masts the appearance almost of human carnage. The sails, with their splotchy zones representing hits from enemy guns, hold our attention because there is a nervy, right-on-the-surface directness about the way he paints these punctures—and also because he makes damaged sails so much like sallow skin on bodies from which too much blood has already been lost. His images of naval warfare have an emotional grimness that we don’t expect from this kind of painting.

When Chambers shifted gears and became a landscapist, his art lost its fiery power, yet his feeling for painting water didn’t desert him. A number of his views of the Hudson at Garrison and West Point, or of the Delaware Water Gap, which take their overall tone from the rivers that form their centerpieces, radiate a sumptuous, glassy calmness. One of his strangest pictures, Flooded Town, a concoction with architecture from different historical periods, is in part about water’s sometimes insidious allure.

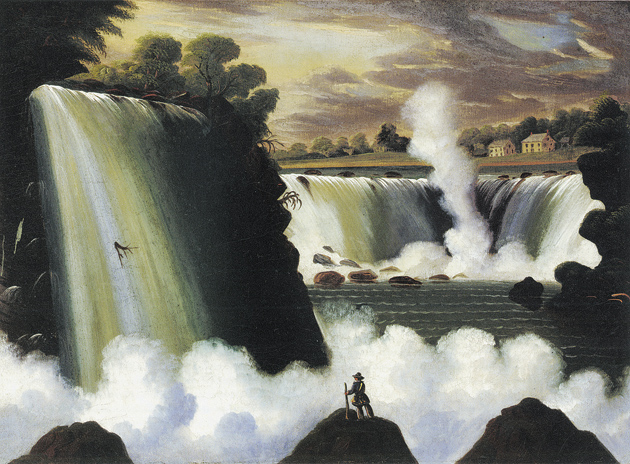

Chambers’s masterpiece, moreover, is not a marine painting. It is Niagara Falls, a brilliantly complex design in dark and light, with any number of curved forms pushing forward and taking us into deep space simultaneously. It is virtually a hymn to water. Water has a crushing force as it pours over the falls and then comes back with a heavenly and orgasmic presence in the form of spray.

Niagara Falls, which has long been in the collection of Hartford’s Wadsworth Atheneum, isn’t especially singled out by Foster in her catalog. But her densely detailed and speculative study, you might say, does justice to the painter of Niagara Falls, who turns out to have been alone among folk or “vernacular” painters in making both sea pieces and landscapes. He also appears to have been the first artist to take the conventions of folk art—especially its way of showing the details of the world, no matter how close or far away they are from us, as so many clear-cut shapes—into landscape.

Advertisement

Foster is particularly acute in delineating the differences between folk artists of various stripes, whose chief loyalty was to their market, and the trained, “progressive” realist painters of the time, whose work was increasingly about observational skills and degrees of “authenticity” and “sincerity” attained by the artist as he recorded his subject. Such a naturalist-artist—a Hudson River School landscape painter on the order of Chambers’s contemporary Thomas Cole, say, or later realists whose search for motifs took them to the far West or South America—might have been completely unable to fathom a Thomas Chambers, who derived his pictures, like folk artists in many cultures, not from close, patient looking at a particular site but from already existing images. Chambers often worked, it is clear, from little black-and-white illustrations in books, which he transformed, in his paintings, with what the progressive nineteenth-century realist painter could only think was an unconscionable degree of liberty.

Foster perceptively writes that since the 1970s, when the idea of modern art as a unified, ongoing endeavor started to disintegrate, distinctions between academic and folk (or self-taught) artists began to be lost. With our “seemingly unshakable sense of irony,” she believes, it is now “harder to measure whatever sincerity or mendacity ‘low’ art may have had in the past.” Yet the question of how we square trained artists with folk or popular (or “outsider”) artists will always be, one suspects and hopes, a somewhat ambiguous issue. Leading us to questions about an artist’s intent and awareness, the problem automatically adds a psychological component to our experience of the work.

On the other hand, we don’t need to be fortified by irony to see that Chambers was at times a powerhouse. And can he be judged only in relation to marine and landscape painters? The range of feeling in his pictures, from the degree of tumultuousness that characterizes some of his harbor views and naval battles to the sense of sheer velocity that marks Niagara Falls —and the stark serenity of his various river scenes—gives his art an expressiveness that the landscape and seascape artists of the time rarely match.

Nor is it quite right to say that he is best seen primarily in the realm of folk art. American painting of the first half of the nineteenth century isn’t crowded with artists who developed different kinds of work over long careers. The period is stamped, rather, by artists who might speak to us with only a type or two of imagery, and whose demarcation as folk or trained painters is somehow less apparent or important than their being so many full-bodied and idiosyncratic voices—and voices we love for the unexpected vistas they open up onto antebellum America. Hicks and Phillips have long secured places in this league, as have the uncategorizable painter of Native American life George Catlin and those classicist masters Raphaelle Peale, perhaps our finest still-life painter of any era, and George Caleb Bingham, whose riverboat scenes exude an unearthly poise. After seeing the present Chambers show, it is tempting to think that he has found a spot there, too.

This Issue

January 15, 2009