Just two years ago, Robert Fagles, shortly before his death, set the bar very high for translating Vergil’s Aeneid.1 Yet already the scholar-poet Sarah Ruden has soared over the bar. She does this despite submission to a trying discipline. She decides to translate one-line-per-one-line, and she uses the iambic pentameter. This means not only that she gives herself less space overall (Vergil’s own 756 lines for Book One of the poem, for instance, to Fagles’s 908), but less space in any single line. She has ten or eleven syllables to a verse, where Vergil and Fagles have up to seventeen syllables. Lines beyond the five beats of iambic pentameter tend to sprawl in English, but Vergil’s hexameter is very disciplined. The wonder of his poem is that it has a melancholy melodiousness while retaining a tight aphoristic ring. Fagles often achieved the former, but rarely the latter. Ruden gets both.

She has to achieve her effects economically. At times, of course, she must sacrifice something. For instance, when a crazed Aeneas is seeking for his lost wife through the falling city of Troy, he relates:

I even dared to shout across the shadows,

Uselessly filling up the roads with grief,

Ceaselessly calling out Creusa’s name.

She does not have room in that last line for the echo-effects Vergil creates:

Nequiquam-ingeminans iterumque-iterumque vocavi.

But Fagles, with greater room for maneuver, cannot equal the original either:

“Creusa!” Nothing, no reply, and again “Creusa!”

One service that translation of a masterpiece provides is reminding us how unreachable the original remains.

Ruden does open up her line a bit by adding an extra syllable at the end of the first line above. It is normal with English pentameter to have the extra unstressed syllable of the “feminine ending,” as with “shadows” above. But Ruden often adds a stressed syllable, a monosyllable following an equally stressed monosyllable (a spondee). At first I found this a little disturbing, as slowing down the run of lines. But Ruden finds many uses for that final spondee. To describe a wasting sickness, for instance, she writes:

We gave our sweet breath up or dragged our lives out.

Three lines show her metrical effects. Two stresses ending the first two lines, and the feminine ending to the third, give a sense of straining to see Dido in the underworld. Aeneas

Encountered her and recognized her dim form

Through shadows, as a person sees the new moon

Through clouds—or thinks he sees it—as it rises.

That last line, its disjointed rhythmic wispiness, almost makes Dido fade again before our eyes. Ruden may be borrowing this effect from the great Dryden:

Doubtful as he who sees through dusky night,

Or thinks he sees, the moon’s uncertain light.

Ruden is good at varying the iambic flow with trochaic words (in which a stressed syllable precedes one that is unstressed):

He fainted into death, like a poppy bending

Its weary neck when rain weighs down its head.

The four trochaic words—fainted, poppy, bending, weary—are followed by seven numbing monosyllables.

The jerking action of lines 10.395–96 is all in the five trochees:

Larides’ severed right hand kept on twitching,

The dying fingers clutching at the sword.

The shimmering effect of 7.8–9 comes from the final three trochees:

The breezes blew past nightfall, and the white moon

Lit up their course—the gleaming surface trembled.

When Juno lures Turnus, Aeneas’ rival in Italy, into pursuit of a phantom shaped like Aeneas, the phantom runs aboard a ship:

The frightened, bolting image of Aeneas

Dove in….

Shades of Burns’s

Wee, sleekit, cow’rin, tim’rous beastie!

Ruden is so virtuosic in her use of the iambic pentameter that she can sometimes suggest the dactyls (one accented syllable followed by two unaccented) of her original without violating the English form:

….All the gods

Murmured their different thoughts, as the woods murmur,

Catching the first gusts, whisking hidden rustlings,

Speaking to sailors of the storm to come.

The second line above contains only eleven syllables and five accents, a proper iambic specimen, yet Ruden is able to squeeze two unaccented syllables between almost every stressed one.

The need for economy makes Ruden bring to bear a fierce alertness before each word of Vergil. At 10.431, ducibus et viribus means “with leaders and forces,” but the basic meaning of vis is “strength,” so she captures the meaning in “leaders and brawn.” Even when it looks as if she is stretching the sense, she has good reason. When Sinon releases the pent-up soldiers from the Trojan horse, Vergil simply says he “loosed the pine holdings,” but Ruden writes that Sinon loosed them and “birthed the Greeks.” She is putting in the verb what the preceding line called “the Greeks enclosed in the horse’s womb”—an image recalled at 6.515. We have to be as alert in reading Ruden as she is in reading Vergil.

Advertisement

That does not mean she is hard to read. Her lines have an easy flow and clarity. Here is a mass funeral scene, as if painted by Turner:

….The beach

Was full of friends who watched friends burn and nursed

The half-dead pyres and clung there till damp night

Wheeled round a sky bejeweled with burning stars.

How is she on the larger meanings of the work? She is the first woman to translate the whole epic, and she seems an unlikely person for the job. She is a Quaker working with a war poem, and she is currently a fellow at the Yale Divinity School. But she is as good with the gore in this place as she was with the raunch in her earlier classical translations, of Petronius’ Satyricon and Aristophanes’ Lysistrata. In fact, a number of scholars have felt that Vergil was working in the wrong genre for him. The poet of idylls and environmental didacticism, of the Eclogues and Georgics, took on epic, the war tale, though some of his modern admirers think he had no warrior in him. But this impression reflects Victorian attempts to turn Aeneas into a gentleman, along with sentimentalism over Dido and a revulsion from his killing of Turnus in the poem’s last lines.

For Vergil and his first audience, Dido was the enemy, was Carthage, and her curse is what brings down on Rome its greatest scourge, the Carthaginian Hannibal. Aeneas has a greater duty to leave her than Odysseus had to leave Circe. And Turnus is doomed the minute he kills the Latin prince Pallas who sided with Aeneas. The Homeric pattern was imperative. As Achilles kills the sympathetic Hector for his slaying of Patroclus, Aeneas must kill Turnus for slaying the lovable Pallas. It is predestined by the logic of the tale and of its source, and premonitions of it have been building by the end. In Book Ten, when Aeneas chases Turnus, he thinks of Pallas and of Pallas’ father, Evander:

Aeneas as he ran kept seeing Pallas,

Evander, and their banquet for the stranger [Aeneas],

And their hands’ clasp.

Not reaching Turnus yet, he strikes down Magus, who pleads for his life. Aeneas answers:

…Turnus did away with bargains

In war the moment that he slaughtered Pallas.

My father’s ghost agrees, and so does Iulus [Aeneas’ son].

We have seen in the underworld the authority of Aeneas’ father’s ghost. Later, Evander says that Aeneas is pledged to avenge his son’s death:

Go, tell your king [Aeneas] that, with my Pallas gone,

I keep my hated life because he knows

His sword owes Turnus to this son and father.

His luck, his heroism are for this.

When Turnus, after breaking the truce that had been made with Aeneas, pleads for his life, Aeneas hesitates a moment —until he sees that Turnus is wearing Pallas’ belt. This is not an appeal to Aeneas’ momentary feelings but to his standing duty. The empire must be built on such determination.

Building an empire does not much appeal to this postcolonial period, so those who would like to save Vergil from himself argue that he was subtly criticizing the empire—the thesis of the so-called “Harvard School” (exemplified by scholars like Adam Perry, Wendell Clausen, Michael Putnam, and others). This is like saying that we now consider hell an inhuman concept, so Dante must really have been undermining that concept while describing it in Inferno. After all, Dante was intelligent and humane, so how could he differ from us on such a fundamental matter? This complimenting of other cultures by saying they were really like us prevents people from meeting the challenge of real differences. Everything in Vergil’s poem says that the costs of empire are very high but are decidedly worth paying.

We are uneasy when poets look sycophantic to their rulers. Vergil is far more adulatory of Augustus in the Georgics than in the Aeneid—there he wonders what divine sphere Augustus will preside over in his afterlife. But the relation of patron and client was a matter of honor in Rome, and a social glue where political party structures were lacking. Discussing the attitude of Alexandrian poets to their rulers (the model Vergil took as his own), Frederick Griffiths said that the ancient poets “would surely be amused by the modern confidence that a network of universities, educational foundations, and cultural ministries shelters art more honorably than might a monarch with taste and flair.”2

The job of Aeneas is to be an epic hero, since the empire of Augustus must be made glorious with epic ancestry. Aeneas, having escaped the agony of Troy’s fall, must go through that agony all over again to make Rome rise. The Sibyl tells him he must refight the Trojan war:

Advertisement

You’ll have another Simois and Xanthus,

A Greek camp, and a Latin-born Achilles,

Himself a goddess’ son. Juno will cling

To hounding you, while desperately you plead

With every tribe and town in Italy.

Again a foreign wife, an alien marriage

Will bring the Teucrians ruin.

Do not give in, but where your fortune lets you,

Go on more bravely still.

This is hardly a cheering prospect. I think of the Virgin Mary telling Chesterton’s King Alfred what lies ahead for him in The Ballad of the White Horse:

I tell you naught for your comfort,

Yea, naught for your desire,

Save that the sky grows darker yet,

And the sea rises higher.

Those lines were recited by some British troops in the trenches during World War I. Aeneas must face the same kind of crushing future.

To brace himself, Aeneas digs into the past. If he must fight the Trojan War again, he needs counsel from the man who shared his first crushing defeat. He must go into death and find the shade of his father. He prays to the Sibyl:

Let me go see my father, face to face.

Tell me the way, open the holy gates.

From fire and a thousand hostile spears,

From the enemies’ midst I saved him, on these shoulders.

He was my comrade over all the seas,

Enduring every threat of sky and ocean;

His weak old age deserved another fate.

He begged me, trusted me to come implore you

Here at your door. Pity the son, the father.

Vergil’s epithet for Aeneas is pius, as his comrade Achates is called fidus. Though Ruden sticks mainly to “staunch” for fidus, she translates pius in various ways—“steadfast,” “good,” “upright,” even “pious.” But the basic meaning is “loyal,” loyal to gods and to his men and to his father. The test of the other loyalties is the bond with his father. Romans honored the interlocking auctoritas of a father and pietas of a son.3 Aeneas must obey when his father lays on him the duty of empire. In the underworld Anchises tells his son:

Others, I know, will beat out softer-breathing

Bronze shapes, or draw from marble living faces,

Excel in pleading cases, chart the sky’s paths,

Predict the rising of the constellations.

But Romans, don’t forget that world dominion

Is your great craft: peace, and then peaceful customs;

Sparing the conquered, striking down the haughty.

No one has echoed the effect of these lines better than Dryden:

Let others better mould the running mass

Of metals, and inform the breathing brass,

And soften into flesh a marble face;

Plead better at the bar; describe the skies,

And when the stars descend and when they rise.

But Rome, ’tis thine alone with awful sway

To rule mankind and make the world obey,

Disposing peace and war thy own majestic way—

To tame the proud, the fetter’d slave to free.

These are imperial arts, and worthy thee.

The key point of this passage for Vergil himself is that it renounces an earlier renunciation. That first recusatio rejected epic for the “thin” and precious verse of Hellenistic poets in Alexandria. Vergil imitated Callimachus when he made this abdication in Eclogue 6 (lines 6–9):

I aimed for poetry of kings and battles,

But Apollo grabbed my ear and told me, “Shepherd,

Your flocks keep fat, your subtle verses thin.”4

Anchises’ charge to Aeneas calls for a counter-recusatio on Vergil’s part. He must reject peaceful poetry and arm himself for epic. Aeneas seeking out his father from the past is a parallel to Vergil going back to find Homer for his new effort. It is a proud change. As Aeneas faces new challenges, Vergil takes up his own poetic aristeia. Plunging into the past was the only way to go forward:

Goddess, direct your poet. Savage warfare

I’ll sing, and kings whose courage brought their death;

The Tuscan army; all Hesperia rallied

To arms. This is a higher story starting,

A greater work for me.

Though the imperial theme swells as the poem builds, it is always there. In Book One (278–279), Jupiter issues this pledge to the Romans:

For them I will not limit time or space.

Their rule will have no end.

The oracle says in Book Three (97–98):

Aeneas’ sons will rule in every country—

His children’s children through the generations.

Members of the Harvard School would take this epic labor away from Vergil. They have that anachronistic thing, a postmodern romanticism, maintaining that all great art must be “subversive.” Vergil must be acquitted of celebrating empire if he is to earn their respect. They maintain this even though the nature of empire is what gives Vergil a nobler claim than Homer’s. Aeneas’ wars are taken up in order to found the Roman state, while the Trojan War had for its only excuse the abduction of a wife.

It is said that Vergil cannot be celebrating empire since there is a persistent sadness in his lines. Knowing the high price of forging an empire does not, necessarily, mean that one should not pay the price. Rudyard Kipling, after all, emphasized the bloody cost of keeping the British Empire—“the white man’s burden”—but did not brush off that responsibility.5 If Vergil is not triumphalistic, that is just a matter of good strategy. Empty optimism would cheapen the victory of Rome. The Stoic rhetoricians denounced celebratory (epideictic) oratory as mere flattery.6 Vergil would have undercut his own argument for empire if he had succumbed to a trivializing giddiness over it.

Ruden is admirably free of Harvard School dogmas, though she received her doctorate from the Harvard classics department. She writes:

It is particularly strange for present-day Americans to offer pious criticisms of Vergil’s praise of imperialism, praise which is blended with forthright sorrow over necessity, and not to see that the tragedies and failures he depicts come mainly from characters being alive and belonging to society.

The translation is alive in its every part. Indeed, I found only one line that is a clunker: “As Rhoetus drove past, making himself scarce” (10.399, for fugientem).

More commonly Ruden comes very close to Vergil’s mark, with a kind of quiet power even in the tumult of a storm:

A long way out, with nothing in our sight

Anywhere but the ocean and the sky,

A blue-black mass of rain and stormy midnight

Loomed in; the water bristled in the dark wind.

All that colossal surface rose in arcs,

Flinging and strewing us across itself.

The storm clouds muffled day, the sky was hidden

In soaking night, fire shattered on and on.

Slammed off our course, we groped through blinding waves.

The sky could not show even Palinurus

The time; he said he’d lost his way in mid-sea.

For three long days (we thought—the gloom confused us)

We wandered, and as many starless nights.

On the fourth day at last we saw land rising:

Some distant mountains and a curl of smoke.

This is the first translation since Dryden’s that can be read as a great English poem in itself.

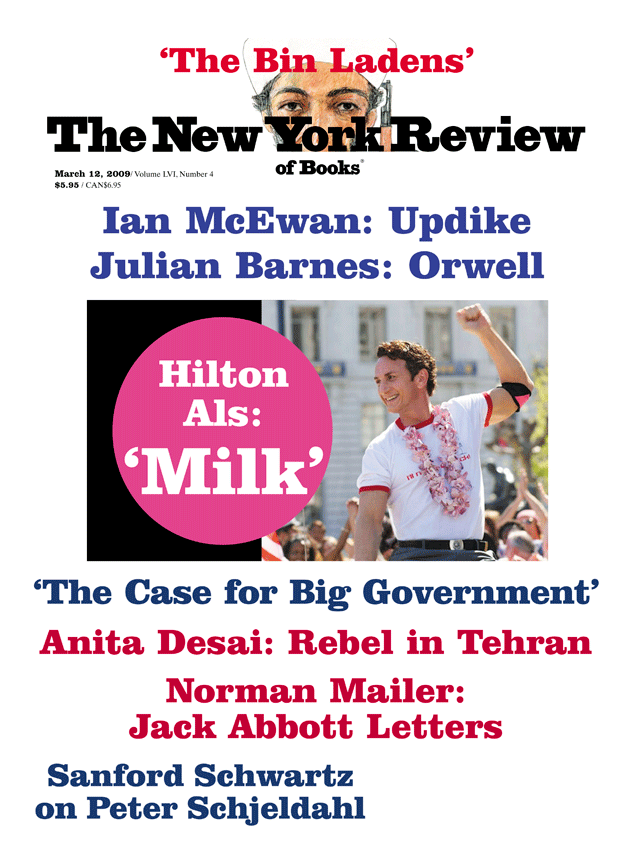

This Issue

March 12, 2009

-

1

See Garry Wills, “The Jolting Shocks of War,” Poetry, February 2007. ↩

-

2

Frederick T. Griffiths, Theocritus at Court (E.J. Brill, 1979), p. 3. ↩

-

3

Maurizio Bellini, Anthropology and Roman Culture, translated by John van Sickle (Johns Hopkins University Press, 1991), pp. 5–13. ↩

-

4

Callimachus, Aitia, fragment 1.22–24 (Pfeiffer): “Lycian Apollo told me, ‘Poet, heap up sacrificial victims as fat as can be, but your Muse, good fellow, keep it thin.'” ↩

-

5

Kipling applied the poem to the American Philippine war, but he had first written it for Queen Victoria’s Diamond Jubilee. ↩

-

6

Epictetus, Discourses, 3.23; Cicero, Brutus, 113–116. ↩