1.

Do you want to become French? It may be easier than you think. Patrick Weil tells us that George Washington was made an honorary French citizen in 1792, and that Bill Clinton, born in Arkansas on what had once been French soil, as part of the Louisiana Territory, was until recently eligible to apply for French citizenship (he did not do so).1

At times, however, it has been hard to become French. The welcome depended not on some fixed French national character but on the country’s perceived needs at the moment. Weil takes the reader authoritatively through the major turning points in French nationality law. His book establishes firmly that it has changed “more often and more significantly than [in] any other democratic nation” since French nationality was first defined explicitly in the constitution of 1790.

Weil begins with the revolutionary legal authorities who first codified French nationality law. They did so, not surprisingly, in opposition to the monarchy’s practice of considering anyone born on French soil the king’s subject. Far from being eternally wedded to the doctrine of jus soli—nationality determined by place of birth—the French, contrary to received wisdom, invented, in 1790, jus sanguinis—nationality determined by paternity. This definition was enshrined in the Civil Code of 1803 and then was adopted by almost all other European states as the influence of the Civil Code spread across the continent.

Weil declines to draw sweeping conclusions about national political culture from these two definitions of nationality. He demonstrates convincingly that no necessary link connects jus soli with open societies and jus sanguinis with racist and exclusionary ones, as has been maintained by some scholars. Dissatisfied with “the study of some isolated element that has no meaning in itself—jus soli, for example, or jus sanguinis,” Weil reaches more deeply to consider how nationality laws have applied in practice, by looking at their “configuration in action and in comparison.”

The French adopted jus soli only in 1889. That change came about in response to France’s first period of mass immigration. Large numbers of Italian and Spanish laborers entered France in the 1880s looking for work, joined by Jews fleeing the pogroms of tsarist Russia. By 1889 the foreign-born had grown to 3 percent of the population. At this moment France became for the first time a nation of immigrants, and indeed the foremost one in Europe, though it has long been reluctant to acknowledge itself as such. Twenty years ago Gérard Noiriel, attempting in a landmark book to awaken France to its true identity as a nation of immigrants, claimed famously that one French person in three had, if one went back three generations, a foreigner in his or her immediate family.2

The French legislators of 1889 worried about clusters of foreigners in the major cities and along the borders, especially at a time of economic depression and low native reproductive rates. They were especially concerned that the children and grandchildren of these immigrants were exempt from the obligations of French citizenship, notably military service. The 1889 amendment to the Civil Code made the children of immigrants residing in France automatically French citizens when they reached the age of twenty-one, and their grandchildren citizens automatically at birth, whether they wanted to be or not.

French citizenship became even more accessible under a new nationality law in 1927, at a time of economic expansion plus demographic panic, when France’s historically low birth rate had been compounded by the loss of 1.3 million young men in World War I. France proposed to relieve its shortage of workers and soldiers by large-scale naturalization.

Weil does not explain the changes in French nationality law purely by their social background, however. After spending eight years reconstituting the history of French nationality policy and jurisprudence, he recognizes the autonomy of individual jurists and expert advisers involved in drafting and promoting this legislation. François Tronchet, for example, president of the highest court (Tribunal de Cassation), who favored jus sanguinis, prevailed in the Civil Code of 1803 over Napoleon, who preferred jus soli in order to obtain more soldiers. He is only the first of a number of strong-minded French jurists who steer events in these pages, as Weil elucidates each transformation in French nationality law with admirable historical specificity.

Weil punctures myths with relish, and one of them is the reputed universalism and openness of French nationality law. He notes that even in periods of openness, it excluded some categories of persons. Women could not be naturalized at all, according to the Civil Code of 1803. This restriction was first breached by the provision of the 1927 law that permitted foreign women who married French men to be naturalized. They did not thereby acquire all the rights of citizenship, as women obtained the vote only in 1945. Until 1927, moreover, French women who married a foreigner lost their French citizenship. Nationality law became fully equal for men and women only in 1973.

Advertisement

The next category excluded was Algerians, who were permitted to have only partial or limited citizenship after 1889. And until 1983, new citizens could not exercise certain professions or fill certain public offices until after a waiting period.

Racial and ethnic criteria for nationality, already proposed in the nineteenth century, gained powerful support in the 1930s, thanks to unemployment, the arrival of numerous Jewish refugees from Eastern Europe, and the naturalization of hundreds of thousands of new citizens under the 1927 law. Weil identifies three “ethnic crises” in twentieth- century French naturalization policy: the “Nazi crisis,” the “American crisis,” and the “Algerian crisis.”

As is now generally known, Vichy France, of its own volition, excluded Jews from political and economic rights. Vichy further obliged Jews to register and interned the foreign-born, restrictions that in 1942 facilitated the Nazi extermination program. Fewer know that in reaction to the perceived laxity of the 1927 law, Vichy France reviewed all the naturalizations accorded under it and denaturalized some 15,000 “unworthy” citizens. Many of these were Jews who thereby lost the protection (feeble as it was) of the French state. Vichy also stripped of French nationality some foreign-born Communists (mostly dissidents from Mussolini’s Italy) and those who joined De Gaulle’s Free France or the Allied armies overseas.

Very few know that Vichy also undertook a general revision of nationality law. Only a German veto prevented its promulgation. The Nazi nationality experts found the Vichy draft (the result of lengthy infighting in which “restrictionists” won out over “racists”) wanting in two respects. It did not explicitly exclude all Jews from naturalization, and it declared French the children born to French women by German soldiers, in flagrant violation of German doctrines of citizenship by paternity.

The most striking innovation of Vichy’s draft nationality law was an ethnic quota system based on the American laws of 1921 and 1924, which set limits that favored immigrants from northern and western Europe over those from southern and eastern Europe. It may disconcert Americans to find themselves cited as a model in this matter by the French exclusionist right, but Weil is just as happy to deflate Americans’ self-satisfied myths as those of his own countrymen.

Another of Weil’s surprises (already, in fact, revealed in his earlier work) is the survival of the quota idea in French politics after the end of the Vichy regime and during the Liberation period. Georges Mauco, a demographer who had advised Vichy on its exclusionary policies, enjoyed the favor of De Gaulle in 1944 and 1945. Mauco’s ascendancy was countered only by other strong-willed officials such as the jurist René Cassin and Justice Minister Pierre-Henri Teitgen. Thanks to them an American-style ethnic quota system was narrowly averted in France after World War II.3

A postwar period of easy entry ended with the “Algerian crisis.” During the 1970s France endured its first major economic downturn of the postwar period. Simultaneously, it made the unhappy discovery that the immigrant masses brought in from former French colonies in North and West Africa to perform menial labor during France’s prodigious postwar boom were not temporary. They were going to remain in France, install their families, and alter the character of the French population for good.

Jean-Marie Le Pen’s National Front emerged in the early 1970s by capitalizing on a backlash against immigrants who were mostly far more exotic in religion and customs than those of earlier generations. President Valéry Giscard d’Estaing responded vigorously to public pressure, trying to undercut Le Pen by borrowing parts of his program. He stopped legal immigration in 1974, except for family unification and political asylum. Giscard further proposed the forced return of some 500,000 “undesirable” immigrants, mostly Algerians. In the end, the expulsions were less draconian than that, but nationality law and policy continued to be passionately debated through the 1990s. In 1998, a new law permitted immigration of people with advanced technical training.

The main innovation of the 1990s was a conservative project to require some sign of positive choice of French identity from those born on French soil to foreign parents, heretofore automatically French citizens. American-style oaths found little favor, but a new law in 1993 required the children of the foreign-born to make a declaration of intent to become French citizens between the ages of sixteen and twenty-one. These restrictions were eased in 1998, and Weil believes that a consensus has been established around automatic citizenship at birth for those born in France of foreign parents, tempered by some element of choice: the right to decline French nationality, or to request it early.4 Even so, obstacles persist in practice, a point he documents in an informative concluding section. Bureaucratic delays, for example, are not uncommon: in one prefecture in 2004, a foreigner who wished to be naturalized had to wait fifteen months for an appointment to submit his dossier.

Advertisement

2.

Becoming French has another dimension, of course, besides the legal one. Naturalized French citizens should also be accepted as authentically French, by themselves and by others. The successes and failures of cultural integration, a matter of intense and increasing attention in France, are given an authoritative and optimistic reading by Jonathan Laurence and Justin Vaisse in Integrating Islam.

French requirements of cultural assimilation for naturalization, like other aspects of nationality law, have varied over time. They have grown stricter since the 1970s, when the long postwar boom ended and the foreign-born population rose to 10.7 percent of the total, a number higher than the European average but about the same as in the United States. Current French naturalization law sets the assimilation bar relatively high. It is unusual for the specificity of its requirement that candidates for naturalization be fully assimilated into French culture, and for the latitude it gives the state to deny naturalization for défaut d’assimilation, insufficient assimilation.

On June 27, 2008, the highest French administrative court, the Conseil d’état, confirmed a government decision to deny French citizenship to a Moroccan woman, Faiza Silmi, who has lived in France since 2000 as the wife of a French citizen, also of Moroccan descent, and who has four children who are by birth French citizens. Mme Silmi recently decided to adopt the burqa or niqab, a full head-to-toe veil that leaves visible only the eyes. The Conseil d’état ruled that

although Mme M.[i.e., Faiza Silmi] possesses a good command of the French language, she has nonetheless adopted a radical practice of her religion incompatible with the essential values of the French community and notably with the principle of equality between the sexes.

Mme Silmi denied that she was subjugated by her husband, and asserted in a press conference that she had chosen the burqa of her own volition.5

The Conseil d’état recognized that Mme Silmi fulfilled the other conditions of nationality. Having been married for at least two years to a French citizen and residing continually with him in France, she was entitled to request French citizenship by declaration. The judges further noted that it was in the government’s authority to deny that citizenship on grounds of défaut d’assimilation. They denied that their ruling contravened the freedom of religious expression.6

This decision was generally approved in France, and not only among conservatives. A strong and long-standing assimilationist current within the French left holds that the acquisition of French values brings personal liberation. This current had already made itself felt in the debate over the 2004 law prohibiting the wearing of overt religious symbols (and most particularly the Muslim headscarf) in French public schools. The Silmi decision was welcomed by François Hollande, then secretary- general of the French Socialist Party, as “a good application of the law.”

There were, however, dissenting voices. Danièle Lochak, a professor of law at the University of Paris-X and a militant for the rights of immigrants in France, observed that “if you follow this logic to its logical conclusion, it means that women whose partners beat them are not worthy of being French.” It was tempting to imagine the judges of 2008 applying, anachronistically, their criterion of marital subjection to all French women married before 1965, the date when married women were first permitted to open a bank account of their own without their husband’s written permission.

All nations require would-be citizens to display some necessary minimum of cultural assimilation. The United States requires candidates for citizenship, in addition to residence, to demonstrate good moral character (defined mostly by a clean judicial record but explicitly prohibiting gambling, prostitution, drunkenness, and polygamy); to show attachment to the Constitution; to be able to speak and understand “words in ordinary usage in the English language”; and to have “a knowledge and understanding of the fundamentals of the history and of the principles and form of government of the United States.” These last three requirements can be fulfilled by rather simple examinations, and may be waived for the elderly or for those with “a medically determinable physical or mental impairment” that affects their ability to learn English. Finally, a candidate for United States citizenship must take an oath of allegiance wherein he or she swears to “support the Constitution and obey the laws of the US; renounce any foreign allegiance and/or foreign title”; and perform military or other government service when required.

France is more exigent about cultural assimilation. Although both France and the United States are nations of immigrants, they think differently about how immigrants relate to the whole. Standard American lore (except among a few WASP nativists) generally considers that successive waves of immigration constitute the nation. Most French suppose that a people who have been French forever make up the nation, into which immigrants are expected to assimilate. Above all, French perceptions of the nation have no room for “hyphenated Frenchmen,” on the model of Italian-Americans or Chinese-Americans.

Each country looks askance at the other model (too often perceived as a stereotype). The French express horror at what they call communautarisme (communitarianism), supposing (far beyond anything in real experience except perhaps for Native American reservations) that the United States is fractured into subnations, each one with its own laws, institutions, and customs, and each one busy “lobbying” the government for special privileges at the expense of the other. In fact, the two models differ more in imagery than in practice, both nations possessing formidable cultural institutions encouraging informal assimilation, including music and sports, and expecting a high degree of it. Laurence and Vaisse take these images too literally, alleging that a unitary French state protects all equally while a weak American state is pushed around by “well-organized minority group lobbies.” The truth lies somewhere between these two abstract “models,” as anyone knows who has observed French farmers, truck drivers, and others bringing the state to its knees by strikes and demonstrations.

Americans, for their part, detect racism and intolerance behind high French expectations of assimilation. They believe that France requires an immigrant to “check your identity at the door,” though a walk on any French city street reveals the enormous cultural variety tolerated there today. No recent French action has so puzzled even sympathetic American observers than the 1994 French ban on the wearing of highly visible religious symbols in public elementary and secondary schools. This ban officially includes yarmulkes and large crosses, and unofficially includes Sikh turbans, which the drafters forgot but which have proven to be a real problem. The law was unmistakably aimed at the Muslim foulard, or headscarf, since the issue was first posed by the expulsion of some scarved Muslim girls from a school in Creil in 1989.7

This law does not forbid Muslim women to cover their heads in public or at university, if they so choose; and it is widely supported by French schoolteachers and other progressives as enabling Muslim school girls to escape from the tyranny of their brothers and fathers in their most vulnerable adolescent years.

Laurence and Vaisse demonstrate convincingly that the foulard ban did not produce the extensive resistance that some Americans predicted. But the foulard issue is only a small part of the problem of Muslim integration. Earlier waves of culturally similar Spanish and Italian immigrants already aroused resentment and sometimes violence in France. In August 1893 between ten and fifty Italian salt workers were massacred by an angry crowd at Aigues-Mortes, on the Mediterranean coast.8 Jewish immigrants of much more divergent religion and culture aroused violence in France and French Algeria during the Dreyfus Affair (Dreyfus himself having been a highly assimilated Alsatian Jew). After the immigrant wave of the 1930s many French accepted Vichy’s brutal exclusion of Jews. The tensions aroused by the Muslims who have dominated immigration into France since 1945 may be even more intractable than those created by earlier immigrations.

Today, France has the largest Muslim population in Europe, about five million, three fifths of whom are citizens. Islam is today the second-largest religion observed in France, after Catholicism, and Muslims outnumber the next three religious minorities together (Protestants, 800,000; Jews, 600,000, also the most in Europe; and Buddhists, somewhere between 150,000 and 500,000). Laurence and Vaisse give us a carefully documented study of the integration of Muslims into French society, solidly based on statistics and poll results. They see integration wisely as a double process, bringing change to the French population as well as to immigrants. They believe that it is, in general, succeeding. Without denying the negative, they see more positive than negative trends. Although their general tone is defensive (they write explicitly to counter “myths” and “exaggerations” that they find in American press coverage of French immigration issues), their final conclusion is cautious: “The only certainty is that both aspects of integration [alienation and acculturation] exist in France today, and they are likely to do so for years to come.”

On the positive side, Laurence and Vaisse note the general desire of most immigrants to be accepted in France and to succeed there. Most statistics are moving in positive directions: better command of French, more intermarriage, more successful careers, and declining birth rates among immigrant families. Religious practice is not more widespread among Muslims than in other religious groups in France. The Muslim population is divided within itself, and does not react as a unit.

On the negative side, racism and discrimination are widespread within the French population. Laurence and Vaisse, despite their generally positive tone, admit with candor that Muslims in France endure daily acts of hostility and rejection in the workplace and job market, in house-hunting, and in ordinary social interactions. Indeed such acts are increasing. The events of November 2005, when the poor outer neighborhoods of the Paris region and a dozen other cities erupted for three weeks in clashes between mostly Muslim youths and the police, following the death of two Muslim youths who hid in an electrical substation to avoid arrest in a Paris suburb at the end of October, aroused as much backlash as they did sober reflection on the causes of the youths’ anger. Here, too, the authors conclude cautiously: “Time will tell which of the two effects—backlash or increased awareness—will prevail.”

Also on the negative side is “re-Islamization.” Young Muslims of the second generation born on French soil—and hence citizens—are more observant than their parents. Laurence and Vaisse analyze this trend with nuance and subtlety, and find it disturbing. The young are not returning to the “family Islam” of their parents, born in North or West Africa, but to a new “globalized Islam” that gives them an identity that a grudging French society has not furnished. Looking for hopeful signs, Laurence and Vaisse find that the youth unrest of November 2005 was not religious in origin. Religious symbols or demands were absent. The problems are economic and social, and Laurence and Vaisse concede that the French authorities long underestimated these problems. Current efforts to catch up may not be sufficient. Car-burnings continue at a shocking level, though they may now reflect more insurance fraud than social unrest.9

Confronting “re-Islamization” is a hardening French resistance to public displays of religion. Although both the United States and France espouse the principle of the separation of church and state, this has profoundly different meanings in the two countries. For the United States, settled in part by people who had been denied religious freedom, it means the possibility of practicing religion as openly as one wishes, although there are limits on doing so on government property or at government expense. The American notion of separation of church and state accepts far more public religious expression than the French one. The US Justice Department, for example, has supported the right of Muslim girls to wear headscarves in public schools.10

French laïcité, by contrast, is rooted in the long fight since 1789 to protect democracy from the Catholic Church, which remained militantly hostile to the French Republic well into the twentieth century. It means restricting religion as fully as possible to the private sphere. This dislike of religious expressions in public already created difficulties for the integration of Jewish immigrants; it makes integrating Muslims harder today.

A final obstacle is French resistance both to “affirmative action” and to ethnic statistics because they smack of communautarisme. It is difficult to remedy the near absence of Muslims in political office and in responsible positions in the private sector without identifying them. President Nicolas Sarkozy is more open to affirmative action than his predecessor, and experiments are underway to bring more Muslims into universities, politics, and business, but they may not be sufficient.

Tensions with Muslim immigrants in France are constantly aggravated by new arrivals. France is a popular destination, and worldwide migratory flows are on the rise. As we have seen, the French effort to shut off immigration has not succeeded. Family reunification and asylum granting still bring in more immigrants than in the days following the law of 1927, and illegal immigration is rampant.

Each wealthy country today has its own Muslim immigrants, its own distinct history of dealing with them, and its own way of integrating them. The United States draws many of its Muslim immigrations from countries with low levels of religious practice, like Turkey and Lebanon, though more Pakistanis are observant. The British have tolerated a high level of religious autonomy among their Pakistani immigrants, but they have begun to watch their radical mosques. France is another special case; its Muslim immigrants are drawn from countries in which there is considerable Islamic fundamentalism while it maintains its high threshold of assimilation. Laurence and Vaisse very properly distinguish among immigrants to France from different national groups, for their degree of religious practice varies as well as their attraction to Islamic fundamentalism. Islamic fundamentalism in the home country can bring both positive and negative results for France. Many have fled Algeria, for example, precisely in order to escape from Islamic fundamentalism there.

Laurence and Vaisse analyze the radicalization that has affected a small minority of frustrated second-generation Muslim youths in France. Britain and Germany, they argue, have more radical imams. The authors are particularly interesting on French efforts to promote a Western Islam limited to the private sphere, as in Sarkozy’s French Council of the Muslim Religion. They argue that Muslims do not vote as a bloc, and that French pro-Arab foreign policy predates their arrival in France. The authors are informative about French counterterrorism efforts. Radical imams are closely monitored and dozens have been deported. American police agencies have worked fruitfully with the celebrated French antiterrorism prosecutor Jean-Louis Bruguière.

The outlook, then, is very much as these two books leave it. The tendency has been toward increasing liberalization and equalization of French naturalization law, and for increasing integration of Muslim immigrants into French society. But emotions and frustrations exist that push the other way, as all three authors acknowledge. The story is not over.

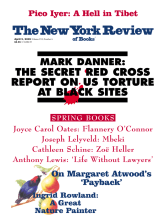

This Issue

April 9, 2009

-

1

Patrick Weil, “Bill Clinton: The French Years,” The New York Times, January 10, 2001. After Weil’s article made this provision of French nationality law notorious, the French parliament abolished it on July 24, 2006.

↩ -

2

Gérard Noiriel, Le Creuset français: Histoire de l’immigration XIXe–XXe siècles (Paris: Seuil, 1988), p. 10. This remains a seminal book today.

↩ -

3

Quotas were abolished in American immigration law in 1965, and had never existed in naturalization law, so French exclusionists surpassed their American nativist models.

↩ -

4

Weil contributed to this liberalizing trend, not only by his dozen scholarly works but by active participation in advisory committees, such as the one that prepared the 1998 law.

↩ -

5

Katrin Bennhold, “A Veil Closes France’s Door to Citizenship,” The New York Times, July 19, 2008.

↩ -

6

Décisions du Conseil d’État. Section du contentieux, 2ème et 7ème sous-sections réunies. Séance du 26 mai 2008. Lecture du 27 juin 2008. No. 286798.

↩ -

7

Weil was a member of the commission for the reinforcement of French laïcité that recommended against the wearing of the headscarf, along with twenty-four other steps that have not been adopted. Initially reluctant, he accepted the ban as a lesser evil, preferring to relieve some girls and teachers of pressure from their families, at the cost of restricting the liberty of a smaller number. See Weil, “Lifting the Veil,” French Politics, Culture and Society, Vol. 22, No. 3 (Fall 2004). France has gone further than any other country except Turkey on this issue, but Muslim headscarves are arousing opposition in all Western European countries. Eight of sixteen German states have banned the headscarf for teachers; the Dutch government is considering a ban on garments that hide the face; and some Belgian municipalities prohibit, for security reasons, garments that hide the face.

↩ -

8

Noiriel, Le Creuset français, p. 260. Laurence and Vaisse minimize the death toll in this famous incident as “several.”

↩ -

9

Agence France-Presse reported on January 1, 2009, that 38,700 cars had been burned in 2008, 6,000 fewer than in 2007.

↩ -

10

Terry Frieden, “US to Defend Muslim Girl Wearing Scarf in School,” CNN .com, March 31, 2004.

↩