In connection with the Frankfurt Book Fair, an international symposium, “China and the World—Perception and Reality,” was held in Frankfurt on September 12 and 13. Under pressure from China, which is guest of honor at the Book Fair, the organizers rescinded invitations to the Chinese poet and editor Bei Ling and the Chinese journalist and environmental activist Dai Qing. After the decision was criticized in the German press, both were allowed to attend the conference as guests of the German PEN association of writers, causing members of the official Chinese delegation to walk out. Following are excerpts from a speech prepared for the symposium by Bei Ling that were published in Süddeutsche Zeitung on September 10.

On a July night in the year 2000, a friend drove me to a printing press in the Beijing suburb of Tongzhou. At the time, I was editor in chief of the [literary] magazine QingXiang, and it was two days before we closed our next issue. I was on my way to delete two words from an article that could have put me in prison. One was “Wang,” referring to the name “Wang Dan” [one of the leaders of the 1989 Tiananmen Square protests]. The other was “anti” (fan), as in anti-Communist. I was committing an act of self-censorship, just as all editors and writers in China still do today. I had no doubt about what I was doing. I simply wanted to avoid endangering myself or the magazine.

The issue in question featured a text by Seamus Heaney. Wang Dan and the phrase “anti-Communist system” would not actually have been much missed. But Lao Mu, one of the founders of Qing Xiang, had sent me a letter that he insisted be printed in its entirety. In it he mentioned his political convictions and Wang Dan. As the editor, I had initially decided to publish the letter in full. Yet although, in the end, I committed the act of self-censorship and deleted the two words shortly before publication, I was unable to protect either myself or the magazine.

The magazine was seized by the Beijing Office of Public Security. I was arrested and detained, without any information released about my whereabouts. I was guilty of a crime that in no civilized country would count as a criminal act: the “illegal publication of a literary journal.” Susan Sontag wrote at the time that my crime should have been called “bringing ideas to China.”

China has to this day no television broadcaster, no radio station, no newspaper, and no publishing house that doesn’t belong to the state or fall under its control. Over the last twenty years, a subtle and exhaustive system of state review has emerged for the publishing industry: at the state publishing houses, texts are examined by different departments as many as five or six times. Publication also requires final review and approval from the state-run media. When rejected at any point in this process, a work cannot be printed. When publishers release a book that is “politically wrong” or “too sexual,” they are threatened with charges of defamation or with being closed down. Publishers that release books that have been banned or that “threaten state security” will be fined or shut down.

In China every author knows what can be written and what cannot. Self-censorship is imperative for survival and for success, especially for novelists. Since market influence, royalties, and potential renown after publication depend on membership in state writers’ associations, self-censorship and censorship by the state have a complicated coexistence. This relationship makes Chinese writers, journalists, and publishers—whether consciously or unconsciously—accomplices of state control over information and the press, which then takes on so-called Chinese characteristics.

Chinese blogs that reveal a personal and independent opinion are shut down. When the regime blacklists an author, he is no longer able to publish in China. His books will disappear from bookstore shelves, and he will no longer receive any public recognition, payments, or royalties.

But for all that I’m not without hope. There has been progress on the difficult path toward press freedom: in some cases, private investors are buying shares of state publishing houses. Independent writers, editors, and booksellers are stepping into positions of responsibility in such publishing houses. With their experience, they will try to circumvent the state censors.

I would on this occasion like to call attention to the Taiwanese section of this year’s Book Fair. Even though Chinese books will also be featured here, there is a separate section that will be devoted only to Taiwanese literature and books that in China cannot be published. Books by banned authors such as the writer Wang Lixiong or the Nobel laureate Gao Xingjian, the National Book Award winner Ha Jin, and also books of my own are the best evidence that China is in urgent need of the freedom to publish.

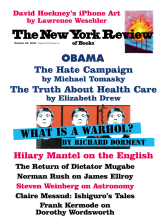

Advertisement

—Translated from the German by Hugh Eakin

This Issue

October 22, 2009