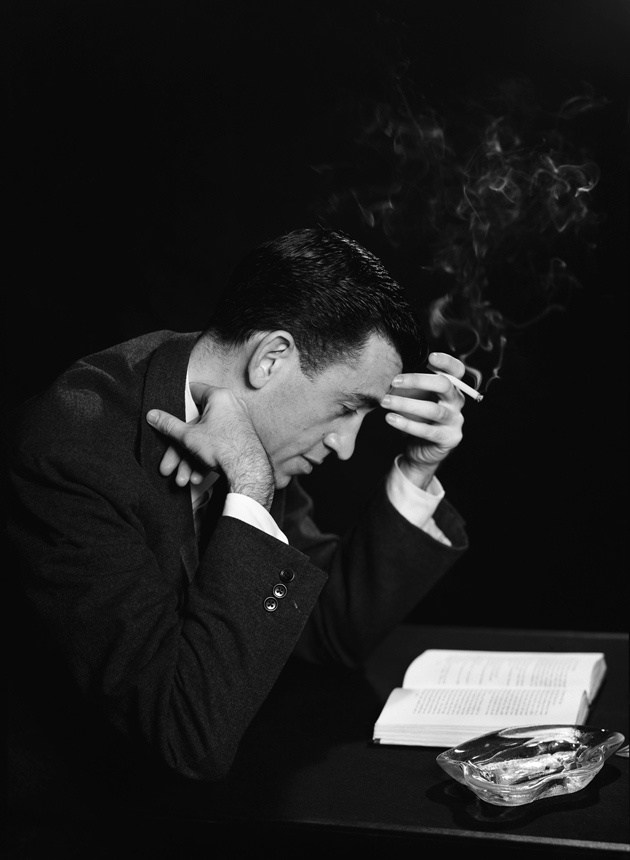

Rereading J.D. Salinger after his death on January 27, I am struck by an improbable connection between his work and that of Jack Kerouac. Both were writing in the late Forties and Fifties, from opposite ends of the social spectrum, but with a relentless ethos of nonconformism at the center of their fiction. Salinger, however, has none of Kerouac’s easy American Romanticism, much less his patriotic celebration of the open road. Salinger’s world is one of constricted New York spaces: bathrooms, restaurants, hotel rooms, buses, a tiny obstructed table in a piano bar where one barely has room enough to sit down. The high cost of not conforming is far more palpable in Salinger than in Kerouac. For Salinger’s characters, to be different isn’t a choice but a kind of incurable affliction, a source of existential crisis rather than social liberation.

There’s no alternative “lifestyle” for Holden Caulfield or the members of the Glass family to retreat to, as there is for the Beats, no group of like-minded adventurers. Salinger’s characters aren’t after thrills. Their quest is for an impossible purity that drives them away from the workaday world, toward a dangerous, self-burying seclusion. “We’re…freaks with freakish standards,” says Zooey Glass to his sister Franny. “We’re the Tattooed Lady, and we’re never going to have a minute’s peace, the rest of our lives, till everybody else is tattooed, too.”

Salinger’s subject is the burden of having these freakish standards, of being what Tolstoy called “an aristocrat of the spirit.” His freaks are the sort most people would envy—good-looking, witty, talented, well off. But they are paralyzed by their uncompromising sensibility. Franny, a gifted actress, abruptly quits the stage to seek the attainment of satori through repetitive, entrancing prayer. Acting embarrasses her. “I began to feel like such a nasty little egomaniac,” she tells her boyfriend. The boyfriend accuses her of behaving as if “you’re the only person in the world that’s got any goddam sense.” He wonders if maybe she’s afraid to compete. “It’s just the opposite,” says Franny.

Don’t you see that? I’m afraid I will compete—that’s what scares me…. Just because I’m so horribly conditioned to accept everybody else’s values, and just because I like applause and people to rave about me, doesn’t make it right. I’m ashamed of it. I’m sick of it. I’m sick of not having the courage to be an absolute nobody.

Effortlessly distinguished, Franny seems the furthest you can be from a nobody; in Salinger’s world this becomes the logical reason for wanting to be one.

Holden Caulfield in The Catcher in the Rye is beset by a similar crisis of authenticity. It isn’t merely that most people are “phony”; the deeper problem is that sincerity itself is suspect. Like the members of the Glass family, Holden lives in a hell of second-guessing, in which every motive—even those behind seemingly altruistic acts—is potentially corrupt. He demands a purity that is impossible because it opposes the basic machinery of human nature. Thus, to be a high-minded lawyer, for instance, who goes about “saving innocent guys’ lives,” would be tainted by the fact that you wouldn’t know

if you did it because you really wanted to save guys’ lives, or…you did it because what you real ly wanted to do was be a terrific lawyer, with everybody slapping you on the back and congratulating you in court when the goddam trial was over…. How would you know you weren’t being a phony? The trouble is, you wouldn’t.

Intent is given equal moral weight to action, even when intent can’t be definitively known. Under the circumstances, the only solution is the renunciation of ambition itself. Salinger’s characters are like aspiring monks with no religion.

Throughout Salinger’s fiction there is a highly defined, consistent aesthetic, so exacting that it negates creative action itself. In The Catcher in the Rye, a virtuosic jazz pianist has stooped to “dumb, show-offy ripples in the high notes, and a lot of other very tricky stuff that gives me a pain in the ass.” The people in the club listening to the pianist roar their approval, “the same morons that laugh like hyenas in the movies at stuff that isn’t funny.” Attending a Broadway play starring the universally worshiped actors Alfred Lunt and Lynn Fontanne, Holden remarks, “They were good, but they were too good.” The delivery of their lines was

supposed to be like people really talking and interrupting each other and all. The trouble was, it was too much like people talking and interrupting each other…. If you do something too good, then, after a while, if you don’t watch it, you start showing off. And then you’re not as good any more.

Holden is instinctively postmodern, too knowing to suspend disbelief, and hyperaware of the motif or trope that is behind every formal performance. At Radio City Music Hall

Advertisement

a guy came out in a tuxedo and roller skates on, and started skating under a bunch of little tables, and telling jokes while he did it. He was a very good skater and all, but I couldn’t enjoy it much because I kept picturing him practicing to be a guy that roller-skates on the stage.

To be a true artist, the performer must give up being on stage.

Near the end of the novel Holden has an elaborate fantasy of living in seclusion in a cabin in the country. “I’d have this rule that nobody could do anything phony when they visited me. If anybody tried to do anything phony, they couldn’t stay.” Holden doesn’t make good on the fantasy, but his creator did, living reclusively in Cornish, New Hampshire, for more than fifty years, in what appears to have been a state of relative contentment. According to Salinger he continued to write about the Glass family during those years. He declined to publish these books, if that’s what they are, while he was alive, disgusted perhaps with the vagaries of “ego, ego, ego. My own and everybody else’s,” as Franny put it. He seemed to regard his literary success as a moral stain. It would be hard to think of a contemporary American writer whose personal life was more true to the ethos of his fiction.

This Issue

March 25, 2010