1.

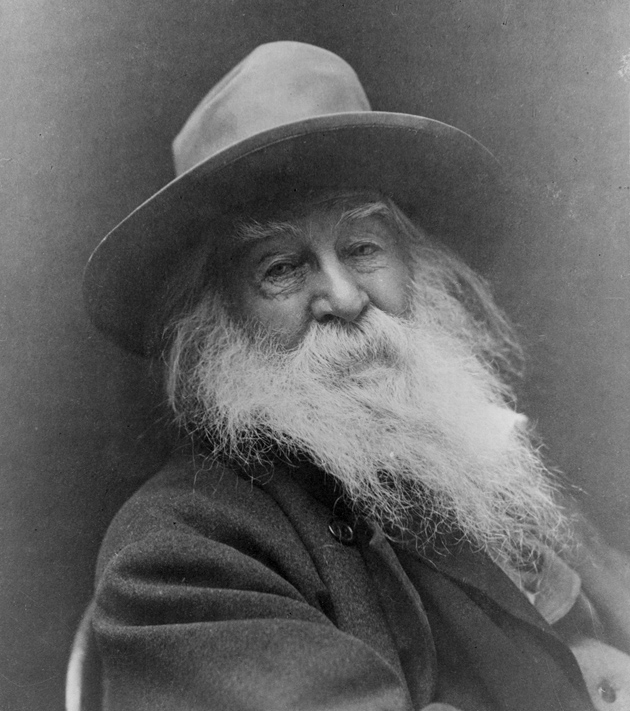

Late in his long life, when he was hampered by a series of devastating strokes and had pretty much given up hope of winning the affectionate following of such best-selling poets as Longfellow or Whittier, Walt Whitman complained to Horace Traubel, his self-appointed Boswell, that he was “not only not popular (and am not popular yet—never will be) but I was non grata—I was not welcome in the world.” He consoled himself with the sour-grapes conviction that if he ever were to achieve widespread acceptance, it could only mean that his revolutionary message had been dulled, and that Leaves of Grass had become just another book of respectable poetry, to place on the shelf alongside The Song of Hiawatha:

I wouldn’t know what to do, how to comport myself, if I lived long enough to become accepted, to get in demand, to ride on the crest of the wave. I would have to go scratching, questioning, hitching about, to see if this was the real critter, the old Walt Whitman—to see if Walt Whitman had not suffered a destructive transformation—become apostate, formal, reconciled to the conventions, subdued from the old independence.

Whitman died in 1892 at the age of seventy-two, but the crest of the wave caught him anyway. It now seems obvious, though it hardly did when the self-published first edition of Leaves of Grass appeared to almost no notice in 1855 (beyond a couple of enthusiastic reviews that Whitman himself wrote anonymously), that American poetry began with Whitman. It is simply impossible, in a way that it is with no other poet—not Bradstreet or Dickinson, Melville or Poe—to conceive of American poetry without him. As Ezra Pound, no particular fan of Whitman, wrote, “It was you that broke the new wood,” though he couldn’t resist adding—as though Whitman were a ham-fisted lumberjack rather than a meticulous sculptor like himself—“Now is a time for carving.”

Whitman’s appeal, at home and abroad, has always been more than merely literary, however. “Whitmanizing is not only a matter of liberating oneself from meter and rhyme,” as the Polish poet Czesław Miłosz observed, “it is also a rapturous movement toward happiness, a democratic pledge of breaking down class divisions, expressed in poetry, prose, painting, theater, and also in a noticeable change of customs.” In the United States, where we are always building a church to something, Whitman during his lifetime had a small but impassioned cult following, which he did much to cultivate. “The priest departs,” he wrote in Democratic Vistas, “the divine literatus comes.” His apostles, as Michael Robertson has shown in his absorbing book Worshipping Walt, regarded Whitman as a prophet and Leaves of Grass as a new Bible, a revelation for modern times, though they sometimes disagreed about precisely what had been revealed, and who could blame them?1

My faith is the greatest of faiths and the least of faiths,

Enclosing all worship ancient and modern, and all between ancient and modern,

Believing I shall come again upon the earth after five thousand years,

Waiting responses from oracles…honoring the gods…saluting the sun,

Making a fetish of the first rock or stump…powowing with sticks in the circle of obis,

Helping the lama or brahmin as he trims the lamps of the idols,

Dancing yet through the streets in a phallic procession….

Sophisticated English readers suspected that the revelation had something to do with those phallic processions, though Whitman fended off their invitations to be more explicit about what he called “the love of comrades,” or about what precisely transpired in his “Calamus” sequence, in which he wrote of “a youth who loves me and whom I love, silently approaching and seating himself near, that he may hold me by the hand.” “In your concept of Comradeship,” the art historian J.A. Symonds wondered, choosing his words carefully, “do you contemplate the possible intrusion of those semi-sexual emotions and actions which no doubt do occur between men?” Whitman vigorously disavowed such “morbid inferences” and claimed, recklessly, that while “always unmarried I have had six children—two are dead—One living southern grandchild, fine boy, who writes to me occasionally.”

It was Whitman’s progressive political message that had wide appeal in Europe and elsewhere, after revolutionary hopes had stalled since the various democratic stirrings of 1848. “The attitude of great poets is to cheer up slaves and horrify despots,” Whitman wrote in the preface to the 1855 Leaves of Grass. “I speak the password primeval,” he proclaimed in the poem he later called “Song of Myself.” “I give the sign of democracy;/By God! I will accept nothing which all cannot have their counterpart of on the same terms.”

Marx’s friend Ferdinand Freiligrath translated Whitman into German in 1868. The Cuban journalist and independence fighter José Martí, who had heard Whitman lecture in New York on Lincoln, introduced him to Latin American readers like the Chilean poet Pablo Neruda, who said that Whitman “taught me to be an americano.” Gavrilo Princip, the Bosnian nationalist who shot Archduke Ferdinand in 1914, believed that he was following Whitman’s orders in bringing down kings—“and that is how,” Miłosz notes wryly, “an American poet was responsible for the outbreak of World War I.”2

Advertisement

2.

More mysterious and inexplicable than the Whitmanizing of the world, however, was the seemingly overnight Whitmanization of Walt Whitman himself. Until around 1855, when he turned thirty-six and published his extraordinary book, Walter Whitman, as he called himself, was, by turns, a carpenter like his feckless and possibly alcoholic father, a schoolteacher in his native Long Island, a printer and journalist in Brooklyn, and the author of a crudely written temperance novel, which sold better during his lifetime than anything else he wrote. Well into his thirties, Whitman was a non-poet in every way, with no mark of special talent or temperament.

It is difficult to match the expansive self-portrait in Leaves of Grass—“Walt Whitman, an American, one of the roughs, a kosmos,/Disorderly fleshy and sensual…eating drinking and breeding”—with the snooty prig who despised the “bog-trotting” Irish children in his classroom:

I am sick of wearing away by inches, and spending the fairest portion of my little span of life… among clowns and country bumpkins, fat-heads, and coarse brown-faced girls, dirty, ill-favored young brats, with squalling throats and crude manner, and bog-trotters, with all the disgusting conceit, of ignorance and vulgarity.

What might account for the sudden appearance—perhaps eruption is a better word—of Leaves of Grass, along with its vivid hero, the all-accepting, all-embracing “rough” depicted on the engraved frontispiece, “hankering, gross, mystical, nude”?

Two new books, a short and impressionistic introduction by the poet C.K. Williams and a scholarly primer on three American poets by William Spengemann, take up the mystery. Both writers rely on decades of energetic historical and biographical research devoted to Whitman, including distinguished work by Justin Kaplan, Paul Zweig, and David Reynolds. Thanks to these biographers, we now know a great deal about Whitman’s passion for Italian opera and American pseudoscience, his interest in liberalizing trends in American Protestantism and pulpit oratory, his omnivorous absorption of popular literature of all kinds, and his moving engagement with the suffering of the Civil War, when he served in Washington as a self- appointed nurse in the horrific hospitals for wounded soldiers from both sides.

While dutifully acknowledging the efforts of previous scholars, Spengemann bluntly insists that no amount of biographical evidence can account for Whitman’s astonishing achievement. “Research of this sort,” he writes condescendingly, “is one of the forms—a perfectly honorable one—that recognition of poetic importance can take.” For Spengemann, however,

no amount of information regarding such matters [as upbringing, early experiences, habits, sexual inclination, and the like] will account for the unforegrounded appearance of the Leaves in 1855, the form those poems take, or the appeal they have held for poets and readers of other times, other places.

The odd word “unforegrounded” presumably alludes to Emerson’s famous letter in which he thanked Whitman for sending him a copy of Leaves of Grass: “I greet you at the beginning of a great career, which yet must have had a long foreground somewhere.”

C.K. Williams is even more insistent that the appearance of Leaves of Grass is fundamentally inexplicable. Struck by the abyss between the dismal things Whitman published before Leaves and the consummate mastery of the book itself, he imagines Whitman undergoing a “conversion experience” around 1855, or perhaps something even more radical:

It’s as though his actual physical brain went through some incredible mutation, as though—a little science fiction, why not?—aliens had transported him up to their spaceship and put him down again with a new mind, a new poetry apparatus. It is really that crazy.

“Something happened,” he concludes, “some utterly mysterious thing happened in the psyche of the poet which still remains the unlikeliest miracle.”

One can see why Williams and Spengemann might respond in this way. Such notions as genius and inspiration are unfashionable today, at least in American universities, where faith is placed instead on careful documentation of those social forces awkwardly referred to as “cultural context.” Nonetheless, one wonders whether an appeal to miracles or abduction by aliens is really in order. There are moments in On Whitman when Williams seems tempted to join the worshipers of Walt, to find something more in the poems than mere poetry. “How much of my admiration for the poems has to do with their aesthetic uniqueness and grandeur,” he wonders, “and how much with the promise they make of a new kind of consciousness, indeed a new genre of identity?”

Advertisement

Williams and Spengemann are on firmer ground when they attempt to describe Whitman’s “poetry apparatus,” which, for both critics, was essentially musical. Spengeman, for whom the central thread in Whitman’s poetry is “a sort of music,” tries to identify its main attributes: the abandonment of meter and rhyme; the various kinds of “doubling” (such as beginning or ending a series of lines with the same words); the juxtaposition of slang with more conventional poetic language to produce a “tune sufficiently musical to be poetic and yet raucous enough to represent modern reality.”

Williams, in his rhapsodic way, makes grander claims for Whitman’s music, which, he believes, was “so forceful, so engrossing, so generative, that it couldn’t have taken him long, a few instants, a few months at most, to realize he’d discovered a musical system that was magically encompassing.” According to Williams, we will never know where Whitman’s music came from, “that surge of language sound, verse sound, that pulse, that swell, that sweep, which was to become his medium, his chariot.”

But once Whitman found this musical undercurrent, “everything else, everything else,” followed: his interest in the modern city with its distinctive sounds (“The blab of the pave, tires of carts, sluff of boot-soles, talk of the promenaders”); his ever-renewed thrill in the human body (“The scent of these arm-pits is aroma finer than prayer”); his sheer wonder, as deep as Darwin’s, at the twin facts of sex (“Urge and urge and urge,/Always the procreant urge of the world”) and evolutionary inheritance (“I find I incorporate gneiss and coal and long-threaded moss and fruits and grains and esculent roots,/And am stucco’d with quadrupeds and birds all over”).

3.

One can see why C.K. Williams, a poet of wide-ranging curiosity and distinctive verbal “music,” might have been drawn to write an introduction to Whitman. In his use of long, flowing lines—sometimes so long that his publishers have adopted unusually wide pages to accommodate them—Williams can seem to be an heir to Whitman’s own poetic practice. There are times in his book on Whitman when Williams confides something that he knows as a poet. Commenting on Whitman’s creation of a poetic persona, he suggests that Whitman wasn’t so much self-made as “self-assembled”: “He put himself together like an inventor in a dream-shed of spare parts; he created himself; he was a fiction, at least at first, but such a glorious one.” Then he pauses to note, “But which of us isn’t a similar jerry-built motion machine? Which of us doesn’t sometimes feel that we’re weird pop-ups of impulses, ambitions, desires, and dreams?” Williams is particularly good at conveying this scattered feeling in his poems.

I wish Williams had allowed himself to be even more personal, more self-revealing, more open and unguarded about what a poet working today might find in the way of inspiration and possibility in Whitman’s work. Especially in the many pages that Williams (who turns seventy-four this year) devotes to Whitman’s tragic final years, one suspects the poet’s own fears coming through, about the sources of inspiration drying up, the music gone. For the most part, however, Williams is content to remain the critic, dutifully comparing, yet again, Whitman to Baudelaire as poets of the modern city and its outcasts, exploring Whitman’s “views” on the equality of men and women, and casting about for something new to say about old cruxes. Was Gerard Manley Hopkins’s ambivalence about Whitman based, as “is generally read,” on his own repressed homosexuality or was it perhaps in response to “Whitman’s frankness about masturbation, which would have been a particularly delicate subject for a lifelong celibate” like Hopkins?

To find out more about what Williams might owe to Whitman, one needs to look at Williams’s own poetry. One of his finest earlier poems, “The Gas Station,” opens with a catalog of writers who could have helped him make sense of the boyhood encounter with a prostitute that follows: “This is before I’d read Nietzsche. Before Kant or Kierkegaard, even before Whitman and Yeats.” Williams’s subject matter can seem Whitmanian, especially in the many poems in which the poet encounters a strange woman in a city, of which “The Gas Station” is an example. In his strong new book, Wait,3 there is a poem of this kind called “On the Métro,” in which the speaker, reading a copy of E.M. Cioran’s The Temptation to Exist, sits down next to a woman in Paris:

She leans back now, and as the train rocks and her arm brushes mine she doesn’t pull it away;

she seems to be allowing our surfaces to unite: the fine hairs on both our forearms, sensitive, alive,

achingly alive, bring news of someone touched, someone sensed, and thus acknowledged, known.

As Whitman asked, “Is this then a touch?…quivering me to a new identity.”

In another poem from the new book, Williams names Whitman as part of “The Foundation” of his own poetic vocation, all that is left from “the building I used to live in”: “and my giants, my Whitman, my Shakespeare, my Dante/and Homer; they were the steel.” Williams invokes these “savants and sages” with their “philosophizing and theories” only to conclude that it was their music all along that counted:

All I believed must be what meanings were made of,

When really it was the singing, the choiring, the cadence,

The lull of the vowels, the chromatical consonant clatter…

“Lull” is one of Whitman’s favorite words, as in these lines from the 1855 Leaves:

Loafe with me on the grass, loose the stop from your throat,

Not words, not music or rhyme I want, not custom or lecture, not even the best,

Only the lull I like, the hum of your valved voice.

Here, one suspects a confluence of Williams’s recent thinking about Whitman’s music and his own efforts to maintain his poetic cadence and lull.

4.

When did the music die for Whitman? Williams thinks that Whitman “lost the connection to his music” soon after the 1855 Leaves. “Trying to keep it going, after the 1860s, into the ’70’s and ’80’s, he kept making new poems, but his locutions become odd and awkward, his rhythms uncertain, his diction sometimes almost primitive.” In the later editions of Leaves, according to Williams, Whitman “all but untuned the original power of his symphony,” and, in a desperate attempt at “sounding like himself,” succumbed to “a kind of dutiful ecstasy.”

One of the pleasures of Robert Hass’s new edition of Whitman’s Song of Myself and Other Poems is that it includes so many poems from Whitman’s later years. Hass, a distinguished poet himself, has long been a champion of Whitman’s very short poems, those “brilliant and surprising experiments” in which, in three or four lines, Whitman composes a snapshot view, as in “A Paumonok Picture” of 1881 or “A Farm Picture” of 1865:

Through the ample open door of the peaceful country barn,

A sunlit pasture field with cattle and horses feeding,

And haze and vista, and the far horizon fading away.

Whitman loved art galleries, and one can imagine him trying, in such poems, to capture some of the effects of the painters of his time, such as the “haze and vista” of the landscape paintings of Martin Johnson Heade or the detailed paintings of athletes by his close friend and admirer Thomas Eakins, as in this poem called “The Runner”:

On a flat road runs the well-train’d runner,

He is lean and sinewy with muscular legs,

He is thinly clothed, he leans forward as he runs,

With lightly closed fists and arms partially rais’d.

Such poems, according to Hass, “anticipate the imagist procedures of the young modernists who came a half century later.”

What these late poems also show is that Whitman had more than one kind of music in his repertory. He wasn’t just the poet of big lines, big ideas, and a big new country—“I am large…I contain multitudes,” as he put it. He was also the poet of the passing glimpse, as in a poem like “Sparkles from the Wheel” of 1871, when he sought to register an old man sharpening a knife, “the sad sharp-chinn’d old man with worn clothes and broad shoulder-band of leather,” and the curious effect these scenes had on the disembodied, camera-like viewer: “Myself effusing and fluid, a phantom curiously floating, now here absorb’d and arrested.”

The shattering experience of the Civil War surely had something to do with this new music. “Death is nothing here,” Whitman wrote from the front, where he had gone in search of his brother George, wounded at Fredericksburg in late 1862:

As you step out in the morning from your tent to wash your face you see before you on a stretcher a shapeless extended object, and over it is thrown a dark grey blanket—it is the corpse of some wounded or sick soldier of the reg’t who died in the hospital tent during the night—perhaps there is a row of three or four of these corpses lying covered over. No one makes an ado. There is a detail of men made to bury them; all useless ceremony is omitted. (The stern realities of the marches and many battles of a long campaign make the old etiquets a cumber and a nuisance.)4

Just as Lincoln’s spare language in the Gettysburg Address and the Second Inaugural introduced a new, chastened tone for a post-traumatic time, one in which “all useless ceremony is omitted,” Whitman found that he needed a new sound for the war poems in his collection Drum-Taps, as in the magnificent “Cavalry Crossing a Ford”:

A line in long array, where they wind betwixt green islands,

They take a serpentine course, their arms flash in the sun—hark to the musical clank,

Behold the silvery river, in it the splashing horses, loitering, stop to drink,

Behold the brown-faced men, each group, each person a picture, the negligent rest on the saddles,

Some emerge on the opposite bank, others are just entering the ford—while,

Scarlet and blue and snowy white,

The guidon flags flutter gaily in the wind.

It is all so simple and clear, so unobtrusively cinematic, like a scene from John Ford. It is also quietly self-conscious about the aesthetic strategies involved—the “line in long array” that is also a “serpentine” line of poetry; the “musical clank” of the men on horseback as well as in the sound of these lines. And then, most importantly, that throwaway phrase—registering the value and aesthetic dignity of each vulnerable young man—“each person a picture.” When Whitman wrote in this way, without fuss, without operatic flights of rhetoric, risking the musical clank, he was still “the real critter.”

This Issue

June 24, 2010

-

1

Michael Robertson, Worshipping Walt: The Whitman Disciples (Princeton University Press, 2008). “The 1860 Leaves of Grass,” according to Robertson, “is particularly insistent upon Whitman’s religious intentions, but his interest in writing a new American bible is evident in every version of Leaves of Grass, from the 1855 first edition on.” ↩

-

2

See the entries for “American Poetry” and “Whitman, Walt” in Miłosz’s ABC’s (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2001). ↩

-

3

Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2010. ↩

-

4

Paul Zweig quotes this passage in Walt Whitman: The Making of the Poet (Basic Books, 1984) and notes that “there is a terse, terrible clarity in these notes that is already stirring toward poetry. But a poetry that is new for Whitman, quieter, more pictorial, as if the powerful scenes of the war could almost speak for themselves.” ↩