Of literary genres none has so diversely and so wonderfully flourished in recent decades as the memoir—not the more staid, stately, chronologically determined life-memoir or autobiography but the highly individualized, often short, lyric memoir of crises, of which William Styron’s Darkness Visible (1990), Frank McCourt’s Angela’s Ashes (1996), and Joan Didion’s The Year of Magical Thinking (2005) are exemplary; and among these none is more beautifully and succinctly composed than Paul Auster’s The Invention of Solitude (1982), written after the unexpected death of his father in 1981.

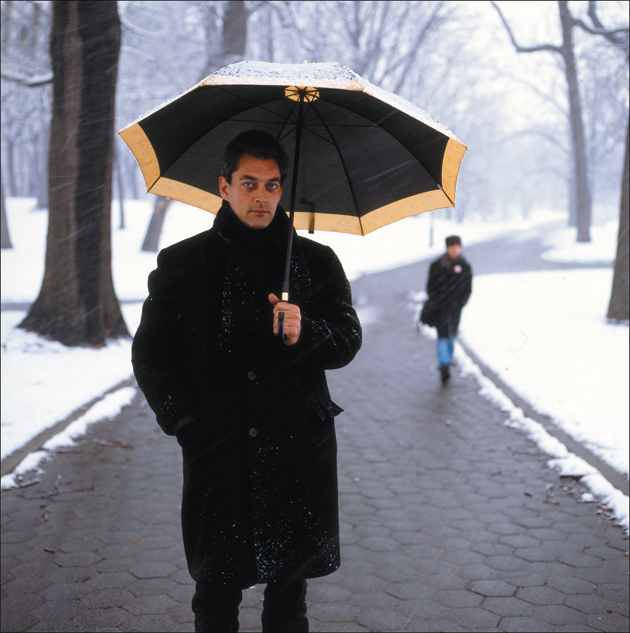

Subsequently, over a career that has included fifteen novels, six works of nonfiction, a collection of poetry, screenplays, and edited books, Paul Auster has become known primarily for his highly stylized, quirkily riddlesome postmodernist fiction in which narrators are rarely other than unreliable and the bedrock of plot is continually shifting. The Invention of Solitude, however, is notable for its frank, candid, understated evocation of filial loss followed not by grief—at least, not conventional grief—but by the numbness of an inability to grieve and the stoic determination to know the elusive, unloved father Samuel Auster—the “invisible” man:

Devoid of passion, either for a thing, a person, or an idea, incapable or unwilling to reveal himself under any circumstances, he had managed to keep himself at a distance from life, to avoid immersion in the quick of things. He ate, he went to work, he had friends, he played tennis, and yet for all that he was not there. In the deepest, most unalterable sense, he was an invisible man.

(Yet a photograph of the deceased Samuel Auster suggests an eerie resemblance to Paul Auster.)

The Invention of Solitude is divided into two thematically symmetrical sections—“Portrait of an Invisible Man” and “The Book of Memory”—that suggest a dialectic as well as a dialogue between the two “Paul Austers”: the one who is the son of the “invisible man” Samuel Auster and the other who is the father of a young son of his own, Daniel. In the first section the author contemplates his father’s death and beyond this, like one peering over an abyss, his father’s mysterious and unknowable life: “I thought: my father is gone. If I do not act quickly, his entire life will vanish along with him.” Like one of his somber detective heroes-to-come in such novels as The New York Trilogy—Auster’s best-known fiction, which reads as if Samuel Beckett were undertaking to refashion one of the more snarled plots of Raymond Chandler—the bereft son explores the large, rather grand if now derelict English Tudor house in a well-to-do suburb of Newark in which his father lived alone for more than fifteen years after the breakup of the Auster family; outwardly impressive, the house is a kind of mausoleum within, a place in which “invisibility” abided.

It is Auster’s hope to reconstruct his absent father’s enigmatic and seemingly entirely self-centered life from an examination of the father’s artifacts—a miscellany of things. And indeed the memoirist does discover astonishing artifacts: a photo album bound in expensive leather with a gold-stamped title on its cover—“This Is Our Life: The Austers”—which is blank inside; newspaper clippings from the early 1900s recounting a lurid family history from when his father was nine years old. The reader is prompted to wonder: was the father’s bemused detachment from life a consequence of this sordid family scandal? Or—more disturbing to consider—did the long-ago incident have little to do with actually forming Samuel Auster’s personality?

In the second, more analytical and speculative section of The Invention of Solitude, “The Book of Memory,” the author speaks of himself as “A.” as he contemplates the paradoxes of memory and the fraught relationships of fathers and sons, sons and fathers; we learn that as a young translator of French poetry and prose, at the start of his writing career, Auster was a disappointment to his father, who’d been a successful—if obsessive, work-addicted—businessman with little sympathy for his son’s preoccupation with literature. (Even the father’s occupation seems symbolic: Samuel Auster owned tenements in an increasingly derelict and dangerous, virtually all-black area of Newark. His work, to which he was addicted, was grinding, unrewarding, and dangerous as well.) With his three-year-old son Daniel, A. takes up the book of Pinocchio, a densely symbolic text exploring the archetypal drama of father-and-son/son-and-father:

This act of saving is in effect what a father does: he saves his little boy from harm. And for [Daniel] to see Pinocchio, that same foolish puppet who has stumbled his way from one misfortune to the next…to become a figure of redemption, the very being who saves his father from the grip of death, is a sublime moment of revelation. The son saves the father. This must be fully imagined from the perspective of the little boy. And this, in the mind of the father who was once a little boy, a son, that is, to his own father, must be fully imagined…. The son saves the father.

As all of Russian literature since Gogol is said to have come out of Gogol’s The Overcoat, so all of Paul Auster’s prose fiction seems to have come out of The Invention of Solitude, from the early New York Trilogy (1985–1986) to the provocatively titled Invisible (2009). Obsessive themes of loss, mystery about whether people actually exist, the instability of identity, and the vicissitudes of chance as well as tales of quixotic quests undertaken by the intense young intellectual men who populate his fiction are suggested in this eloquent memoir, a remarkably accomplished and mature first book with which readers unschooled in the playfulness of metafiction and narrative intertextuality might begin if undertaking to read Auster’s now considerable oeuvre.

Advertisement

In Auster’s new novel, his sixteenth, aptly titled Sunset Park, a tormented and self-exiled son, Miles Heller, returns to New York City to be reconciled with his father, from whom he has been estranged for seven and a half years, with results that are initially promising but soon turn bitterly ironic. The novel is narrated in Auster’s characteristically spare, understated prose, through a chorus of persons who are acquainted with Heller. A brief detour brings us into the PEN American Center office in New York City, where the campaign to free the Chinese dissident Liu Xiaobo is being undertaken by one of the characters in the novel—(with quite admirable results, since the imprisoned Liu Xiaobo is the 2010 recipient of the Nobel Peace Prize).1 But aside from this campaign there are few distracting postmodernist incursions in this melancholy comedy of naive and unworldly idealists who are defeated by the obdurate reality of contemporary America in its economic, political, and moral decline.

When we first meet him, in the “sprawling flatlands of South Florida” where he’s currently in exile, Miles Heller is a young man of twenty-eight who, for all his intelligence and sensitivity, seems incapable of establishing a place for himself in the adult world. Following the accidental death of his older stepbrother, in which Miles had been involved, he has become a wanderer like the biblical Cain; in the eyes of an admiring friend with whom he has kept in contact over the years, he is a “grief-stricken boy with no illusions, no false hopes”—“only half a person…his life…sundered”—yet:

Miles seemed different from everyone else, to possess some magnetic, animal force that changed the atmosphere whenever he walked into a room. Was it the power of his silences that made him attract so much attention, the mysterious, closed-in nature of his personality that turned him into a kind of mirror for others to project themselves onto, the eerie sense that he was both there and not there at the same time?

Miles is a sympathetic person, not unlike other loner-protagonists in Auster’s fiction, but he seems trapped in a kind of spiritual stasis: he’s a dropout from Brown, has an “addiction” to reading, and sees himself as an enemy of “the system,” yet he lacks ambition and has “no clear idea of what building a plausible future might entail for him.” During his seven and a half years of self-imposed exile he has worked at minimally paying jobs; he has remained estranged from his father and stepmother, who have no idea what his motives are for breaking with them so abruptly. It’s an inspired choice for Auster to place Miles in such desolate and demeaning work for a corporation that clears out “trashed” foreclosed homes after their evicted tenants have departed:

In a collapsing world of economic ruin and relentless, ever-expanding hardship, trashing out is one of the few thriving businesses in the area…. In the beginning, he was stunned by the disarray and the filth, the neglect. Rare is the house he enters that has been left in pristine condition by its former owners. More often there will have been an eruption of violence and anger, a parting rampage of capricious vandalism….

Miles is also a photographer, obsessed by recording “abandoned things”—which is, say, virtually everything he discovers in the bankrupt flatlands of foreclosed Florida. He has amassed an archive of thousands of photographs:

He understands that this is an empty pursuit, of no possible benefit to anyone, and yet each time he walks into a house, he senses that the things are calling out to him, speaking to him in the voices of the people who are no longer there….

Miles is haunted by the memory of his stepbrother’s death, which occurred on a country road in Massachusetts with no witnesses, when the boys were scuffling together and sixteen-year-old Miles unthinkingly shoved his infuriating stepbrother into the path of an oncoming car:

Advertisement

He doesn’t know if Bobby’s death was an accident or if he was secretly trying to kill him. The entire story of his life hinges upon what happened that day in the Berkshires, and he still has no grasp of the truth, he still can’t be certain if he is guilty of a crime or not.

The incursion of chance into our lives is another prevailing theme in Paul Auster’s fiction, and so in Miles’s case his young life as well as that of his family has been irrevocably altered:

Whenever he thinks about that day now, he imagines how differently things would have turned out if he had been walking on Bobby’s right instead of his left. The shove would have pushed him off the road rather than into the middle of it, and that would have been the end of the story, since there wouldn’t have been a story….

Like a Beckett character, if lacking Beckett’s darkly radiant poetry, Miles Heller is absorbed in his dead-end but mesmerizing half-life; he remains haunted by the past he has broken with, and has written fifty-two letters to a friend his age back home, inquiring after his father and stepmother. Like Miles’s own mother, who’d left him and his father when he was very young, Miles is one of the “walking wounded”—“damaged souls”—who can be wakened from his trance only by a kind of counterenchantment.

Miles is jolted out of his isolation by falling in love with a young girl named Pilar whom he first sees in a park, reading The Great Gatsby. Though Pilar is considerably younger than Miles and “underage”—initially he’d thought she was “even younger than sixteen, just a girl, really, and a little girl at that, a small adolescent girl”—he begins a sexual relationship with her that seems reckless and ill-advised:

Because of the way she looks at him, perhaps, the ferocity of her gaze, the rapt intensity in her eyes when she listens to him talk, a feeling that she is entirely present when they are together, that he is the only person who exists for her on the face of the earth.

And:

He is a prisoner of her ardent young mouth. He is at home in her body, and if he ever finds the courage to leave, he knows he will regret it to the end of his days.

Pilar is the novel’s least plausibly drawn character: she seems scarcely to exist apart from Miles’s extreme need, the very figure of masculine erotic fantasy. When one of Pilar’s sisters learns of the affair she threatens to report Miles to the police, which forces him to leave town, and to return to New York City and the world he’d tried to leave behind.

Once Miles returns to Brooklyn, Sunset Park splits into myriad perspectives to include a sympathetic group portrait of people linked by circumstances as by a gigantic spiderweb. We meet Miles’s father and stepmother Willa; we meet Miles’s birth mother Mary-Lee Swann, an actress rehearsing, appropriately, the role of Winnie in Beckett’s Happy Days; we meet Miles’s friend and confidant Bing Nathan, to whom he’d written his letters, and Bing’s squatter friends, who are illegally living in a city-owned, abandoned house in Sunset Park, Brooklyn. Of these, the most interesting is Miles’s father Morris, who has spent his adult life “scrambling to publish worthwhile books” under the imprint Heller Books; it’s Morris’s rueful thought that if Heller Books goes bankrupt, he can write a memoir titled Forty Years in the Desert: Publishing Literature in a Country Where People Hate Books. Though Morris is allegedly a man of old-fashioned values and integrity, he’d had a pointless love affair that resulted in his wife Willa being infected with a venereal disease, precipitating her departure to Exeter, England; for much of the action of Sunset Park, Morris is conflicted between following Willa to England to bring about a reconciliation and remaining at home in the hope of being reconciled with his exiled son Miles.

In a plot twist typical of Auster’s fiction we learn in a flashback that Morris had long ago hired a private detective to track down his missing son but when the detective located Miles, on four separate occasions Morris chose to observe him rather than speak with him; he had even witnessed Miles’s first encounter with the high school girl Pilar Sanchez in a park in Florida—he even knows that she was reading The Great Gatsby. On these occasions the stoic father grieves at a distance:

always tempted to step forward and say something, always tempted to pick a fight with [Miles], to punch him, to take him in his arms, to take the boy in his arms and kiss him, but never doing anything, never saying anything, keeping himself hidden, watching Miles grow older, watching his son turn into a man as his own life dwindles into something small, too small to care about anymore….

Squatting in Sunset Park in a “dopey little two-story wooden house…looking for all the world like something that had been stolen from a farm on the Minnesota prairie and plunked down by accident in the middle of New York” are Bing Nathan and two young women, the would-be artist Ellen Brice, who suffers from a mild sort of schizophrenia and has attempted suicide out of her “fear of dying without having lived”; and the self-loathing “meaty girl” Alice Bergstrom, who works for the PEN American Center while writing a Ph.D. dissertation on American culture in the years following World War II. Alice’s argument is that

traditional rules of conduct between men and women were destroyed on the battlefields and the home front, and once the war was over, American life had to be reinvented…. [Americans had] lost their appetite for domesticity.

In her pursuit of this idea Alice is dedicated to deconstructing relevant texts and films of the era, including William Wyler’s 1946 film The Best Years of Our Lives—“The national epic of that particular moment in American history…[a] story that was being lived out by millions of others at the time.”

Miles’s only friend is the hyperactive Bing: “the warrior of outrage, the champion of discontent, the militant debunker of contemporary life who dreams of forging a new reality from the ruins of a failed world.” Bing is something of an autodidact philosopher: a “large, hulking presence, a sloppy bear of a man…a wide and waddling two hundred and twenty pounds” and “a boisterous child, a noisemaker of undisciplined exuberance and clumsy, scattershot aggression.” Bing’s “business” is the Hospital for Broken Things on Fifth Avenue in Park Slope, Brooklyn; mirroring Miles’s fascination with abandoned things, Bing is devoted to repairing cherished objects from past eras: manual typewriters, fountain pens, mechanical watches, record players, rotary telephones:

His shop provides a unique and inestimable service, and every time he works on another battered artifact from the antique industries of half a century ago, he goes about it with the willfulness and passion of a general fighting a war.

Bing is unapologetically sentimental and a bit silly, yet his devotion to useless things is touching, like his indignation at the American capitalist-consumer society that makes of him a sort of Noam Chomsky manqué, lacking a platform to express his ideas as well as a political vision or coherent plan for revolution beyond squatting in the mock-idyllic “prairie” house in Sunset Park—a surely doomed Utopian venture. In the 1960s, Bing and his friends might have been able to establish a rural hippie commune, but in the twenty-first century, in a far less indulgent and economically straitened United States, these dropouts from adult society have no future.

Sunset Park is a somber novel, moving with less dramatic urgency and fluency than Auster’s more typical work, like the recent metafictional mystery- adventure Invisible; it’s a nostalgic valentine of the American past in which, as in Auster’s more playful postmodernist texts, there are reminiscences of his beloved baseball players. Auster, a lifelong baseball fan, is unabashedly sentimental in recounting the vicissitudes of American baseball, particularly those involving “the tragic destinies of pitchers.” (Is it skeptical to suggest that the “tragic” experiences of pitchers are not of more inherent significance than the tragic experiences of individuals who are not professional baseball players?) “Baseball is a universe as large as life itself,” Miles believes; even a litany of comical names is holy, to be shared with his beloved Pilar as they lie in bed together leafing through the 1985 Baseball Encyclopedia: “‘Boots’ Poffenberger”—“Whammy Douglas”—“Cy Slapnicka”—“Noodles Hahn”—“Wickey McAvoy”—“Windy McCall”—“Billy McCool.” But mostly baseball yields sorrow, for the revered players of Miles Heller’s youth—still more, the players of Paul Auster’s youth—are aging and dying.

So too the idyll in the house in Sunset Park ends abruptly for the young squatters, who have ignored eviction notices yet are surprised and furious when at last New York City police officers show up to throw them out, and not gently. In this climactic scene, in which crucial events occur almost too rapidly to be absorbed by the reader, Alice is injured when an “enormous” policeman pushes her down a staircase; noisy Bing is arrested; Miles loses his temper and strikes a police officer in retaliation for his abuse of Alice, and he and Ellen Brice flee the scene, hiding for a while in a Sunset Park cemetery. Miles is advised by Ellen and by his father to turn himself in to the police but of course Miles refuses, preferring to return to his life of isolation and detachment, and leaving both his father, with whom he’d been reconciled, and his beloved Pilar behind.

Sunset Park would appear to be a pessimistic allegory of contemporary American life in the spiritually bankrupt decade following September 11—most crippled are members of a generation no longer young yet far from mature, in a netherland of protracted adolescence. Miles, Bing, Alice, and Ellen believe themselves on the cusp of radical change, but are defeated by their own ignorance and unworldliness; the allegedly charismatic Miles is seen by Alice as “old.” It’s as if he has “been in a war, and all soldiers are old men by the time they come home, shut-down men who never talk about the battles they have fought.” Even Miles’s father, who had so longed for his son to be returned to him, ruefully acknowledges to himself:

Now that you and the boy have spent an evening together, you find yourself curiously let down. Too many years of anticipation, perhaps, too many years of imagining how the reunion would unfold, and therefore a feeling of anticlimax when it finally happened, for the imagination is a powerful weapon, and the imagined reunions that played out in your head so many times over the years were bound to be richer, fuller, and more emotionally satisfying than the real thing.

Auster is being doubly ironic here, for this “real thing” is—of course—as much of a fiction as the romantic “years of imagining.”

Sunset Park ends in an ecstasy of self-pity and self-abasement as Miles Heller flees New York City and what might have been a fulfilled and mature life. He sees himself as a “Telemachus” who has failed the “Odysseus”-father, as he has been, if but inadvertently, the accursed Cain who has killed his brother Abel, by this action destroying his own life as well:

The name Homer makes him think of home, as in the word homeless, they are all homeless now, he said that to his father…he has let his father down…and as [he drives] across the Brooklyn Bridge and he looks at the immense buildings on the other side of the East River, he thinks about the missing buildings, the collapsed and burning buildings that no longer exist…and he wonders if it is worth hoping for a future when there is no future, and from now on, he tells himself, he will stop hoping for anything and live only for now, this moment, this passing moment, the now that is here and then not here, the now that is gone forever.

This is an unexpected ending to a circuitous story of a son at last reconciled with a genuinely loving father—a father who is the antithesis of the “invisible” father of The Invention of Solitude. Yet it’s an inevitable ending, given Miles Heller’s immaturity and the “collapsing” world beyond the romantic dream of Sunset Park.

This Issue

December 23, 2010

-

*

Paul Auster is a vice-president of the PEN American Center. ↩