I once owned a black car that my husband insisted was green, even though the bill of sale said “onyx.” Then one day about 50,000 miles in, and just for a minute, as the light hit the car in a certain way, I saw what he must have been seeing, and it made me wonder: If my black is someone else’s green, is our understanding of color personal and idiosyncratic? Even when we are looking at the same thing, are we seeing the same thing?

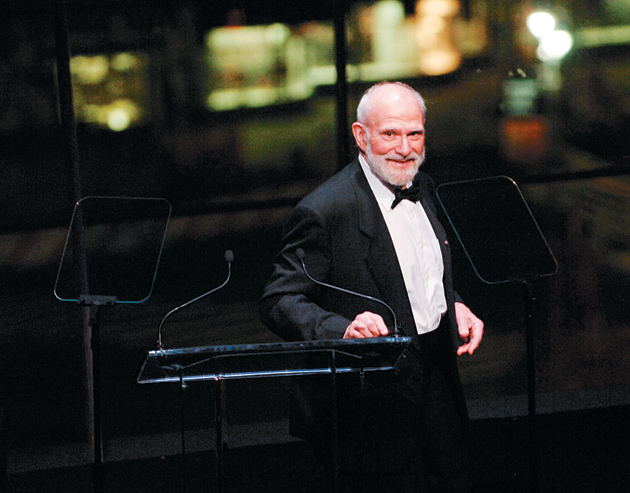

Reading The Mind’s Eye, Oliver Sacks’s latest book, is like standing in that ray of sunlight: it questions perception. Sacks is, arguably, the best-known neurologist in the world. It’s a distinction he’s earned over fifty-odd years, not for his stellar lab work or cutting-edge biomedical inventions, but for something far more basic—his ability to tell stories. In medicine today there is a penchant for “translational science”—doctors who bring the insights they gather from the examination of cells to their patients in the clinic and the insights they gather from patients back to their labs. Sacks, too, is a translational scientist, but in an altogether different way: he has taken what he has learned from patients in nursing homes and hospitals and brought it to us, his readers. And his readers, in turn, have brought him more patients and more cases that often make their way into his practice and his pieces. In book after book, Sacks has taken the patient history—the most basic tool of medicine—and turned it into art. By his telling, the brain, his bailiwick, is made more mysterious, not less, and it is through that mystery that Sacks elucidates it.

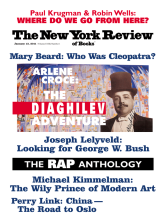

Like many of his earlier and immensely popular volumes, The Mind’s Eye is primarily a collection of pieces published over the past few years in The New Yorker. Like those other books, this one gains its substance and power from the quirkiness and variability of human experience, rather than from an overarching theme or grand conclusion. The brain plays tricks. The eyes play tricks. Oliver Sacks delights in this biological chicanery and hands off his delight in words. Invoking Wittgenstein in an essay about a woman who learned “by a combination of gestures and mime” to communicate without speech, Sacks writes that

the philosopher…distinguished two methods of communication and representation: “saying” and “showing.” Saying…is assertive and requires a tight coupling of logical and syntactic structure with what it asserts. Showing…presents information directly, in a nonsymbolic way….

The philosopher might have been writing about Sacks himself, for Sacks is a literary, medical, narrative showman. He presents cases. They are, on their face, sui generis. Pat, the woman who was able to converse without conventional language, represents nothing more than herself, yet by telling her story, Sacks enables the reader to make his or her own assertions about meaning. Is Pat’s experience replicable? Sacks doesn’t say.

It is well established that the brain can and often does “repair” itself after an insult like a stroke or head injury by recruiting undamaged areas and pathways to preserve function—that it is “plastic.” It’s also well known that sensory deprivation of one sort—being unable to hear, for example—can lead to enhancement of other senses. The conventional wisdom is that blind people hear with more dimensionality than sighted people. There’s a certain appealing rough justice to this. It suggests that perception is an equation with a fixed sum, so that what one loses in one realm one gains in another: one way or other the variables add up.

But oddly, a loss of sight can also lead to greater visual acuity, a condition that would seem, on its face, both impossible and perverse. Sacks explores this phenomenon in the book’s title essay, which, like most of the pieces in The Mind’s Eye, is a testament of, and homage to, the brain’s stunning capacity to overcome itself. He tells of four people, memoirists all: an English theologian named John Hull, an Australian psychologist named Zoltan Torey, a French Resistance fighter named Jacques Lusseyran, and a German woman, Sabriye Tenberken, an educator in Tibet (and the inventor of Tibetan Braille). All had lost their sight after some years of being sighted, yet none experienced blindness in the same way. Traveling through Tibet, Tenberken, for instance, constructed detailed visual pictures of the landscape using her senses to, in a way, triangulate synaesthetically what was before her. It wasn’t necessarily accurate, but she could see it, nonetheless.

Hull, by contrast, saw nothing with his mind’s eye. Despite holding on to some vision until he was nearly fifty years old, when he lost his sight he lost his visual memory—the ability to recall what he had already seen—soon after. When that was gone, Hull entered what he called “deep blindness,” where he could not conjure up any images at all, not even familiar ones, like those of his wife and children. Yet once immersed in the dark, the world opened for him in formerly unimaginable ways. His thinking and writing took on a clarity not reached before, and his experience of the physical world grew richer. He could hear and smell a landscape, for instance, and through his heightened senses construct a (nonvisual) topography, knowing, for instance, precisely where the grass ended and the forest began, even from a distance. (Rain on grass sounds different from rain on leaves.)

Advertisement

Torey’s experience of blindness, on the other hand, could not have been further from Hull’s. After an industrial accident irreparably damaged his corneas when he was a young man, Torey was keen to hold on to his visual memory. Not only did he not slip into the hermetic darkness of deep blindness, he built up a reservoir of visualization to the point where he could compute large sums on an internal blackboard and see a gearbox in three dimensions—from the inside out. So convinced of his ability to see in this way, Torey would step out onto the roof of his house at night—what did it matter?—to repair it, disconcerting the neighbors, but doing a creditable job.

Lusseyran’s experience was different still. After becoming blind at eight years of age, he at first slipped into a state akin to Hull’s deep blindness. Eventually that gave way to a luminous, imagined, highly visual world. “The visual cortex, the inner eye, having been activated, his mind constructed a ‘screen’ upon which whatever he thought or desired was projected and, if need be, manipulated, as on a computer screen,” Sacks writes. In Lusseyran’s words:

Names, figures and objects in general did not appear on my screen without shape, nor just in black and white, but in all the colors of the rainbow…. In a few months my personal world had turned into a painter’s studio.

Lusseyran’s extreme visual acuity—more precise than Tenberken’s—especially his ability to move images around his screen, and thereby visualize strategies for defense and attack, proved invaluable to his fellow Resistance fighters. That, and his unerring ability to smell a traitor.

Four experiences of blindness and four distinct ways of seeing. Whether meaning to or not, Sacks brings neurology back to where it began, in philosophy, where questions of perception are questions of epistemology: How do we know what we know? One answer, suggested by these very different stories, is that knowledge derived from conventional sense data—from eyes that see light and ears that distinguish sound—is limited. Impairments might actually be enhancements or, at least, give rise to them.

Language is, perhaps, the second most obvious way that humans acquire knowledge after the sensory information that comes to us as a corollary of sentience. Speech, gestures, the written word all pertain, but of these reading is of a higher order, being composed of symbols that need interpretation. Strokes and other brain traumas often render people speechless, incapable of making intelligible sounds or any sounds at all. This is what happened to Sacks’s patient Pat, a formerly voluble woman, following a stroke. Yet as her case demonstrates, it’s possible to bypass spoken language and develop a rich gestural vocabulary in its place. While Pat was no longer able, in Wittgenstein’s terms, to “say,” she became a master of showing. Indeed, as Sacks observes, “her powers of depiction, spared by the stroke, were remarkably heightened in reaction to her loss of language.” But what happens when the language lost is the symbolic kind—the letters on the page, the notes on a staff?

Sacks recounts the cases of two people, a concert pianist in New York named Lilian and a novelist in Toronto named Howard Engel, both of whom had lost the capacity to read. Each had written to Sacks after reading his previous work, telling him about their strange debility. Yes, they had written to him, and that was part of the strangeness, for while neither could read anymore, both could still write, and no less intelligibly (except to themselves) than before. For Lilian, the alexia (the term for losing language in this way) began with musical notes, not letters: suddenly they were no longer decipherable to her. She could still play the piano and continued to give concerts and teach, but only by drawing on her lifetime of practice. Not only was her musical memory intact, the longer she was alexic, the better and deeper it seemed to get.

Advertisement

Like Zoltan Torey, the blind Australian who was able to manipulate large figures in his head once he lost his sight, Lilian was now able to hear music with greater fluency, and this gave her the ability to arrange and rearrange scores mentally, without the need to put pen to paper. Eventually written language began to desert her, too, and a few years after losing the ability to read notes, she was unable to read words. After that objects became strange, and then faces. Though her vision was intact, she was becoming blind.

Something similar happened to Howard Engel, though in his case the alexia, which came on suddenly, was the result of a stroke, where for Lilian it was caused by a slow-moving degenerative brain disease. One morning Engel awoke, went out to retrieve The Globe and Mail, and couldn’t imagine why it had been published that day in Serbo-Croatian. None of the words made sense, nor did the street signs on the way to the hospital, nor the words “emergency room,” which is where he landed. It was an especially cruel affront to a man who had constructed a life out of words. Because of that, and against all odds, Engel was determined to read again. And he did. As Sacks points out, no matter what language a person reads, the same area of the brain, the interferotemporal cortex, the visual form area, is activated, allowing recognition of letters and words. But reading is a complicated and interpretive activity that also relies on other areas of the brain. In Engel’s case, though these other areas survived the stroke, they would be of little use if he could not decipher the lines and squiggles—the Serbo-Croatian—he was seeing.

On the other hand, if he could begin to make them out, those other areas of the brain could help him parse their meaning as they collected into words and sentences. Engel began as a child begins, relearning the alphabet, making out words, letter by letter. And then, because the brain is made of motor neurons as well as sensory neurons, and because muscle memory often persists despite other impairments, Engel began to enlist his fingers and even his tongue, tracing the shape of each letter on the page, or in the air, or on the roof of his mouth or the back of his teeth, to “see” them. “This enabled him to read considerably faster (though it might take him a month or more to read a book he could previously have read in an evening),” Sacks writes. “Thus, by an extraordinary, metamodal, sensory-motor alchemy, Howard was replacing reading by a sort of writing. He was, in effect, reading with his tongue.”

As disturbing as Engel’s condition, or Lilian’s, or the four blind memoirists’, or Pat’s, the dominant sensibility Sacks conveys when telling their stories is curiosity. These people and their maladies and their adjustments don’t simply engage him, they appear to delight him. “Look at what the brain can do!” he seems to be saying. “Isn’t it amazing? The human capacity for resilience appears to begin at the cellular level. It is not just a matter of will, it is a feature of biology!” This sensibility takes on a particular poignancy when, halfway into The Mind’s Eye, Sacks reveals that his interest in blindness and ways of seeing is not simply clinical. In 2006, without warning, a gaping hole developed in his visual field. Parts of the world that he knew, objectively, were there, suddenly were not. Not long afterward he was diagnosed with an ocular melanoma: a tumor in his right eye.

Sacks, of course, has written about his own experience before, and even in this collection, before revealing his illness, he makes use of his own neurological history. But here, as before, this is less an exercise in autobiography and more a way of illustration. In an essay about prosopagnosia, the inability to recognize faces, Sacks talks about his own lifelong trouble identifying people by sight. He might know them by the dog they are walking, or because of an unmistakable facial landmark, like a bushy mustache or bulbous nose, but the face itself, its particular geometry, does not add up for him. Even his own face is the face of a stranger. “Thus,” he writes, “on several occasions I have apologized for almost bumping into a large bearded man, only to realize that the large bearded man was myself in a mirror.” For Sacks, face-blindness appears to have been hardwired, a property present from birth, while for others it may come later in life, from a stroke or a disease like Alzheimer’s. The pathologies are different—indeed, it’s not clear if inborn face-blindness, though it poses many problems, is a pathology—but either way, the perceptual problems and the coping strategies are the same. Sacks can attest to this. His authenticity is animating.

Even so, it is one thing to have trouble seeing faces, and another order of magnitude to have trouble seeing at all. Sacks chronicles his cancer with a certain professional dispatch, recounting what happened in diary entries as his visual field contracts, grows dim, and gets treated (with an embedded radioactive plaque accessed by cutting the ocular nerve). Even in the midst of the worst of it, Sacks stays attentive to the quirky clinical details.

On January 15, 2006, he writes:

Everything in the right eye is swimmy, not only metaphorically but literally so—I am looking through a shifting film of fluid. The shapes of everything are fluid, moving, distorted. I imagine my retina almost afloat in the fluid pooling beneath it, changing shape like a jellyfish, or maybe a waterbed.

Sacks continues on like this, recording the fluctuations of eyesight, the strange distortions, the desertion of his peripheral vision. While he never stops being the observant doctor, he eventually slips into the role of patient, too, with the full range of patient emotions—anxiety, fear, petulance, pain, hope, frustration, confusion. Suddenly the book, which had the quality of a leisurely walk along an interesting and agreeable path, becomes urgent and frightening. Unlike Sacks’s other patient histories, this one is happening in real time. And unlike his other well-known foray into autobiography in Uncle Tungsten: Memories of a Chemical Boyhood (2001), where he recounts his young boyhood years in a Dickensian boarding school during World War II, this one is less determined. The outcome is unknown.

Nor does his illness follow a predictable pattern. Unsettling effects arise randomly, catching Sacks off-guard and requiring him (and his brain) to adapt to yet another state. It leads, for example, to the loss of stereoscopic vision, so that he sees everything on the same plane—a fire engine might seem to be impaled on a car or a building scaffolding carried on a man’s back—and to waking, visual hallucinations, and to random blobs and tufts scattered throughout his visual field. Then, in 2009, Sacks’s vision deteriorated further: there was a hemorrhage behind his right eye, and the blood pooled, rendering it essentially blind. “Neurologists talk of ‘unilateral neglect’ or ‘hemi- inattention,’ but these technical terms do not convey how outlandish such a state can be,” Sacks writes.

Years ago, I had a patient with a startling neglect of her own left side, and the left side of space, due to a stroke in her right parietal lobe. But this had not prepared me at all to find myself in a virtually identical situation (though caused, of course, not by a cerebral problem but by an ocular one). This came home even more forcefully when [my assistant] Kate and I finished our walk and headed back to my office. I walked ahead and got into the elevator—but Kate had vanished. I presumed she was talking to the doorman or checking the mail, and waited for her to catch up. Then a voice to my right—her voice—said, “What are we waiting for?” I was dumbfounded—not just that I had failed to see her to my right, but that I had even failed to imagine her being there, because “there” did not exist for me.

Of all the stories in The Mind’s Eye, Sacks’s is the only one without resolution. There remains a chance that the blood will dissipate and he will regain some sight in his right eye. (This was his good eye, his left having been injured when he was a boy.) Sacks remains hopeful—the title of this piece is, after all, “Persistence of Vision.” Reading it, one is struck by the persistence of the writer, and grateful for his enduring perspicacity, so clearly independent of what his eyes can or cannot see. It is a neat trick when the point of a book is made not by saying and not by showing, but by being.

This Issue

January 13, 2011