What a road we have traveled to reach this point. Just a month or two ago, no one would have suggested that a popular uprising in Egypt would successfully topple one of the region’s longest-serving autocratic leaders. Now, many major newspapers and journals praise the courage of the protesters and speculate about continued democratic progress for the Egyptian people.

Yet alongside these congratulatory tones, there is also a current of worry. How democratic will Egypt become? How can the West aid this transition? Whom should we be talking to, and how? Some of the loudest voices warn of imminent Islamic takeover and imply that talking directly with groups such as the Muslim Brotherhood might be dangerous. This perspective is hardly surprising. Deep suspicion of new, popular movements in Middle Eastern and Muslim countries is widely accepted in the West.

We should not allow ourselves to be affected by this fear. Almost ten years ago, the international community agreed that military action was needed in Afghanistan and that dialogue with the Taliban and its supporters would have no place in that strategy. We have since learned the cost of this belief. What was once considered heretical is becoming conventional wisdom. While a military presence is still needed, Afghans and their international partners must find a way forward through diplomatic dialogue with the Taliban.

Together, these experiences demonstrate the centrality of a question that is likely to become more urgent in a shrinking world: Should we talk to those who attack our societies, challenge our most deeply held values, and violate rights we consider fundamental?

This is no mere philosophical question—a fact that was personally hammered home for me three years ago. Late in the afternoon of January 14, 2008, I was—as foreign minister of Norway—meeting with Mrs. Sima Samar, Afghanistan’s brave human rights commissioner, at the Hotel Serena in Kabul. Suddenly the clatter of gunfire echoed down the hallway. We felt the hotel shake from several explosions. Two suicide bombers, members of the Taliban, had attacked the hotel. For three hours, chaos reigned as we were evacuated room by room. I escaped unharmed, but others were not so fortunate. Six innocent civilians, including a Norwegian journalist, were killed. Six more, including a senior member of my team, were seriously wounded. A Taliban-affiliated group took responsibility for the cynical attack. It was a heartbreaking experience. And didn’t it show the futility of dealing with groups like the Taliban?

A year and a half later I found myself struggling with a similar dilemma in a setting about as far removed from Kabul as one can imagine—peaceful and affluent Geneva. Originally conceived as a way to confront and reduce racist ideologies and behaviors, the closing session of the UN World Conference against Racism (known as Durban II) had turned into an event that some saw as little more than a highly publicized soapbox for anti-Semitism and anti-Western attacks. The April 2009 conference was particularly controversial because Iran’s president, Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, delivered a divisive and vitriol-laden speech attacking the West and Israel. In response, more than twenty delegates from the EU walked out (a half-dozen other nations, including Israel and the US, had already refused to attend the conference).

Two completely different events. One from the landscape of the violence and chaos of terrorism; the other from the world of diplomatic communication. Taken together, they exemplify what for many people would prove the dominant perspective of the last decade: that diplomacy and dialogue are less and less useful and relevant to international politics.

In my view, this is precisely the wrong conclusion to draw. Despite our experience at the Hotel Serena, I remain convinced of the need to encourage direct political talks between all relevant political parties in Afghanistan. And despite the fact that we found Ahmadinejad’s claims abhorrent, our delegation decided to remain for his address. We believed that it was important to listen to his words and then to use our position as the next speaker to directly engage and challenge his hateful claims.

Why do I believe that it is important to continue to carry on a dialogue even under conditions as difficult as these? Because my five years as a foreign minister have convinced me that as challenging as it is to continue to talk in such circumstances, the consequences of not talking are often far more dangerous. Used correctly, dialogue is the essential diplomatic tool that allows us to pursue our common interests in an increasingly complex and fast-moving world.

Certainly, military power has an appropriate place in foreign policy. Norway’s security, like that of most other countries, continues to rely on a credible military capacity and our membership in NATO. But as policymakers, we know that military force alone is ill-suited for dealing with a growing number of situations that currently shape international and interstate relations.

Advertisement

I have seen firsthand how the international forces in Afghanistan have tried to avoid civilian causalities. I doubt that there is another armed conflict in history where so much effort has been invested in ensuring that only military targets are pursued with force. And yet it only takes a small number of ill-fated incidents to make much of the goodwill generated by aid and local outreach programs evaporate. When civilians are killed or injured, images of destruction are quickly transmitted throughout the world. If military force has always been a poor means of changing the convictions and allegiances of local populations, it is particularly ineffective in the era of mass media.

In such a world, I find it difficult not to conclude that strategies based on dialogue are indispensable and must be defended, and further strengthened. I am not suggesting that contact and talk can solve every conflict, or that dialogue can replace military power or the use of force entirely. The lesson of the Cuban missile crisis is clear about this—a willingness to judiciously apply military pressure combined with a willingness to communicate was the right course of action. With respect to Iran we have the option of progressively adopting tough sanctions while simultaneously calling on the international community (and Iran) to keep diplomatic channels open.

Moreover, I do not believe that we have to be willing to talk to everyone, under any circumstance, regardless of other considerations. All countries have their “red lines” that cannot be crossed. Yet I believe it is important to resist the temptation to disavow on moral grounds dialogue with any group or state whose ideology and aims we view as dubious or dangerous. For example, I believe that we should not assume that a group must be excluded from dialogue simply because some states have named it a “terrorist” organization. When asked about his country’s strategy against terrorism, my colleague Marty Natalegawa, Indonesia’s foreign minister, put it bluntly: “The effort to fight global terrorism is not a war. If it was simply a war, then it’s simply about the application of force, brute force.” In this context, the defining question shouldn’t be who we should allow ourselves to talk to. Rather, the question we should ask is under what circumstances, and about what topics, it is appropriate to talk.

Unfortunately, there is no easy, universal rule that answers the specific questions of when and how to conduct dialogue with an adversary. We need to make judgments on a case-by-case basis. The role of Islamic groups in the Middle East is of particular importance. Should we talk to Hamas? In Norway we condemn Hamas’s attack on innocent civilians, and strongly oppose its ideology. We believe that Hamas must respect previous agreements and obligations entered into by the PLO, renounce the use of violence, and recognize Israel’s right to exist. Hamas—or any other single faction for that matter—has no right to decide over war or peace on behalf of the Palestinian people.

So, why do we nonetheless support a policy of allowing contact and talks with a group such as Hamas? Because beyond doubt Hamas represents a significant part of Palestinian society—and it now controls a territory, Gaza, that includes around 1.5 million Palestinians. It is thus a social, political, religious, and also a military reality that will not simply go away as a result of Western policies of isolation. There are constituencies within Hamas that seem open to dialogue and there are signs that these parts of the movement might be willing to support a two-state solution and recognize Israel’s right to exist.

How do we test this possibility? Engaging in dialogue with a group and its members is not the same thing as legitimizing its goals and ideology. Used skillfully, engagement may moderate their policies and behavior. It may also fail. But the blockade and other attempts to completely isolate Hamas have been a clear failure, allowing the Hamas leaders to play the martyr in the international media and to further embed themselves in Gaza by becoming the de facto providers of goods and services. The isolation has also further driven Hamas and its constituency into the hands of Iran.

Because of this, I think the international community was mistaken when it did not engage in relations with the Palestinian unity government in 2007, a government that included all Palestinian factions—among them the elected Hamas representatives—and was endorsed by the democratically elected President Mahmoud Abbas. A policy of engagement with that government would have extended neither full cooperation with it nor financial support until key changes in policy had been made. But the Middle East Quartet—the UN, the US, the EU, and Russia—could have held talks with the unity government. It would thus have recognized that the Palestinian factions had made a historic effort to unite, and that dominant factions within Hamas had chosen to work through politics.

Advertisement

The Quartet could have used dialogue to encourage further steps toward serious negotiations. Instead the unity government was treated like a pariah—with predictable results. Elements within Hamas who had opted for politics and who were potentially willing to explore negotiated solutions were left empty-handed and without influence. Young people were radicalized. The government broke down and Hamas and Fatah violently opposed each other, further complicating prospects for peace in the Middle East. We cannot, of course, be sure that diplomatic talks and contact would have been more successful. But it seems unlikely that they would have been less successful.

The events of the last month and a half in Egypt add credence to this belief. Many in the West worry that strong popular movements in the Arab world, secular or Islamic, would provide an opening through which radical Islam will clamber. This, in turn, has dissuaded policymakers from supporting democratic changes and engaging in dialogue with various civil society groups in ways that we regularly do in many other parts of the world.

The situation in Egypt demonstrates just how unwise this approach is. The recent weeks have revealed that the communications revolution of the last decade has profoundly changed politics in the Middle East. Diffuse networks of groups can now collaborate and communicate in ways that are not controlled by any single ideology or regime. The young populations of the Middle East can increasingly express their desire for a better life. The events in Egypt and elsewhere also highlight the fact that although radical and dangerous Islamic factions exist, moderate, pragmatic, and influential Islamic groups and wings of groups also have their own power.

These are realities not only in Egypt but throughout much of the Middle East. What can Western policymakers do to address the fact that the politics of the region will be increasingly bottom-up, influenced by the voices of a young, diverse civil society? To begin with, we need to recognize that we can no longer concentrate so heavily on negotiations with elites. We need to support political solutions that will take effect at the popular level: economic development, better health care, institution-building, and on-the-ground initiatives in support of peace.

In order to do this, we have to find ways to engage in political dialogue also with groups that are different from us. As has become vividly clear in recent months, many governments in the Middle East are not able to correctly interpret and respond to the signals sent by civil society. But we need to find better ways to be directly in touch with groups in civil society, which now have their own demands and methods of organizing. In a world in which information technology gives the voices of diffuse groups much more potential influence, we have no choice but to engage them. But it is also in our own interests. Would it not have been valuable to have engaged the Muslim Brotherhood and other groups in a critical dialogue earlier? This isn’t a particularly drastic suggestion. It simply means that we take the groups that are part of “the people” in the Middle East as seriously as we do in our own and other democratic societies.

Understanding the diverse nature and interests of, and within, different Islamic groups—and the strategic value of dialogue with them—is also why we should support a policy of dialogue between various Afghan factions, including parts of the Afghan Taliban. Portraying the Taliban as a monolithic entity distorts and ignores the realities of southern Afghanistan in ways that make it impossible to develop realistic and effective strategies on the ground. It is conventional wisdom that governance is the key to a peaceful settlement in Afghanistan. But without a political process of dialogue that encompasses all representative groups, governance will remain flawed and fragile.

As defenders of dialogue, however, we need to go further. We need to remind the international community that dialogue with some parts of the Taliban and other Afghan parties is intrinsically necessary because any long-term solution in Afghanistan (at least one that does not involve a large international military presence) must ensure that important constituencies within the Pashtun community and traditional tribal power-holders are willing to support (or at least not militarily resist) the Afghan state. Certainly, this is far from an ideal situation. Even moderate elements of the Taliban endorse ideas and policies—toward women, for example—that are anathema to me and to many others. Moreover, it won’t be easy to identify a solution everyone can live with. But the truth is that while it will be difficult to do this through dialogue, it is impossible to do so without it.

Many of those who most strongly oppose dialogue in international relations prefer to live in a world they wish existed. Some of them believe that imposing a particular political system in other countries by the use of force is worth large expenditures of wealth and of life. Others take the view that a “clash of civilizations” requires us to build walls to protect our society from an inevitable global threat. Some maintain that the willingness to negotiate and compromise will be interpreted as a sign of moral and military weakness. None of these approaches points to a plausible way forward. And the cost of pursuing any of them is high.

In contrast, defending and employing dialogue is neither a naive nor utopian strategy. It shows strength to be willing to talk to the adversary. It is not weakness. And it is not cowardice to debate your opponent and try to persuade the world to follow you by speaking your values. It may take some courage.

In this sense, the defense of dialogue springs from a perspective best described as principled realism—an approach that attempts to find solutions that both improve the world and recognize the constraints of the current global order. As defenders of dialogue, we always keep open the option of walking away rather than talking. But we also believe that we shouldn’t be so quick to do so. The fact that there may be some positions and conflicts that cannot be resolved does not mean that the possibilities of dialogue shouldn’t be actively explored. Dialogue is more important to our globalized world than it ever has been. We must therefore defend it all the more strongly. At a time that seemed far more dangerous than our own, John F. Kennedy formulated the principle that has since been too often disregarded: “Let us never negotiate out of fear. But let us never fear to negotiate.”

When I visited Cairo recently I met many of the key players behind the Egyptian uprising. My aim was to understand the driving forces behind this historic process of change. I met representatives from the groups who had filled Tahrir Square, including the Muslim Brotherhood. Should I not have met them? The Muslim Brotherhood is a social and political reality in Egypt. It was not in the forefront, but it played a decisive part in the January and February uprising and it will be a player in the upcoming fragile process of building a democracy in Egypt. I can see no valid reason why we from the West should not recognize this reality and why we should not engage with them as we do with the other factions that are now forming in Egypt.

Our challenge today is to support the democratic forces in Egypt. We should exclude none. I disagree with the Brotherhood on many important issues, such as the role of religion in politics, the rights of women, and the rights of minorities. But by not talking to its representatives we make no difference. We should hold the Brotherhood accountable and expose its members to universal standards on issues such as equality between all religions, between women and men, and the key principles of democracy. Singling them out for exclusion could push them into the role of martyrs, further strengthening the perception of the West’s double standards. And who knows, perhaps the Brotherhood, with its visible diversity, may emerge as a social and political counterweight to the antidemocratic sentiments that do exist in Egyptian society, both within the remnants of the previous regime and among much more traditionalist Islamic salafi groups.

—March 8, 2011

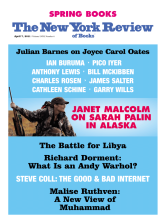

This Issue

April 7, 2011