An important thing to know about memoirs is that although there are a lot of them already, there will soon be more. Seventy-six million baby boomers are reaching retirement age. Many of us own computers, and we find ourselves fascinating. Perhaps the best way to regard the future deluge is to take a glass-half-full approach and assume that certain of these oncoming memoirs will be good. You have to concentrate on the good ones, as you would on a friendly face in a crowd, and not let the others distract you. Almost a Family, John Darnton’s memoir of his life as the son of a New York Times correspondent killed in World War II, is a good one—exciting, deeply felt, evocative of past worlds and times, and full of first-rate reporting. Because his birth preceded the earliest of the baby boomers by a few years, Darnton comes ahead of the rush; that he has a great story to tell is another advantage.

Having written a book about my own family I know that the reader’s first question is “Why should I care about your family?” The author needs to get up a head of steam right at the start to override that, and Darnton does. On page three his father, Byron “Barney” Darnton, a veteran correspondent for the Times, records the author’s birth with a note in the margins of Mark Twain’s Life on the Mississippi, the book he is reading in the hospital waiting room. The date is November 20, 1941. Two and a half weeks later the Japanese bomb Pearl Harbor. Though Barney is forty-four, he gets himself an overseas assignment, sails to Australia, flies to New Guinea, and joins a small force of US soldiers on two antiquated trawlers making an amphibious counteroffensive against the Japanese. While the troops wait offshore in a bay near the landing site, a single plane appears, drops several bombs, and leaves. Barney and one other man are killed. We are on page nineteen.

The author’s mother, taking care of the new baby and his three-year-old brother, Bob, in the family’s home in Connecticut, is washing dishes at the moment of Barney’s death. She has a sudden sense that it has occurred. The next day the army notifies her. President Roosevelt sends her a personal letter of condolence. Arthur Sulzberger, the publisher of the Times, and his wife, Iphigene, drive to Westport to see her. Five planes fly over the house in formation and dip their wings. The next year, a new merchant ship built to carry war supplies to Europe is named for Barney. His wife and the two boys go to the shipyard in Baltimore and she smashes a bottle against the ship’s bow, christening it the Byron Darnton. Bob, by now four, writes “BoB” on the hull in blue crayon. The ship makes many voyages across the North Atlantic with war materiel for the Russian front. In March 1946 the Byron Darnton runs aground off Scotland in a gale, and breaks apart minutes after the rescue of those on board.

Bob grows up and becomes a historian. John becomes a reporter for the Times and a novelist. Both have distinguished careers. When they are in their sixties they learn that on the island of Sanda, thirteen miles off Scotland’s Kintyre Peninsula, is a tavern said to be the most remote in the British Isles, and its name is the Byron Darnton. Naturally they go there. The tavern, it turns out, has indeed been named for the wrecked ship, pieces of which still can be seen by the shore. The tavern owner knows nothing about Barney, he just found the ship’s name poetic. Bob and John take a walk to the wreckage and, with their wives, drink at the tavern with the owner and some of the guests. Among these are a group of men who are very friendly, but evasive when asked about themselves. After the men leave, the owner tells the Darntons that they were the band Pink Floyd.

This last detail is the kind of fact that makes me love reality. Appearing on page thirty-four as the out-of-nowhere capper to the already remarkable summary of Barney’s death and remembrance, it gives the reader strong momentum to continue into the book. Pink Floyd! The author himself may not realize the aptness. Roger Waters, Pink Floyd’s famed songwriter, lost his own father in the war, at the Anzio landing, and a lot of Waters’s work has to do with that death. The band was probably on Sanda as part of their reunion in 2005.

A good memoir requires ripeness; that is, it tends to work best after time has passed and some of its principals are gone. Darnton’s mother survived his father by twenty-six years—not a lot, considering she was nine years younger than he. She died in 1968 at the age of sixty-one. The part of the book covering John and Bob’s childhood is largely about her and her worsening alcoholism, and the honesty and frequent bleakness of his picture probably would not have been possible were she alive.

Advertisement

Barney’s death had left her in a chronically difficult position that the short-lived solicitousness of his colleagues did not improve. She was a single woman with little money trying to make her way as a writer and a newspaper journalist while raising two boys. When she took a job at the Times, the hard-charging guys there, one or two of them Barney’s former friends, scorned her for suggesting that news about women and their problems was neglected. When she wrote a book, The Children Grew, about Barney’s death and the effect of its aftermath on the family, Shirley Jackson, a writer best known for her short story “The Lottery,” gave it a crushing review in the Times. There are reviews from which authors never recover, unfortunately.

As Darnton makes clear, The Children Grew actually was sort of sappy, and its upbeat portrayal far from what he remembered of those hard years. Darnton’s correction of the story is gripping and often painful to read, but it sometimes blends into other accounts of children who suffered from and prevailed against screwed-up parents. As I read I occasionally slid into confusion between this book and Geoffrey Wolff’s outstanding memoir The Duke of Deception, which, in parts, covers the same places and times. Darnton’s mother’s first name was Eleanor but she went by the nickname Tootie. Wolff’s stepmother’s first name was Alice but she went by the nickname Tootie. Darnton’s mother drank; Wolff’s father drank and committed frauds. Darnton’s mother’s maiden name was Choate; Wolff graduated from Choate, Darnton got kicked out of Andover. As boys, both lived for some years on the Connecticut shore—Darnton in Westport, near the Saugatuck River, and Wolff in Saybrook, near the Connecticut River. In young manhood both traveled around the country and had minor episodes of stealing cars. And so on. Similar confusions might become more common with the future multiplication of memoirs. Readers, concentrate!

Darnton was a preteen relaxing on a summer day with his mother at the beach when suddenly she sat up and said to him, “Watch out for The New York Times. They use you like a sponge. They squeeze you dry and then they toss you away.” As often happens with parental cautions, hers only made the hazard alluring. Barney had been a much-admired figure—debonair, skillful, funny, self-deprecating, brave. During his sons’ mostly crummy childhood he remained an ideal for them, more present and influential, perhaps, than if he’d been there. Throughout his youth Darnton thinks and wonders about his father. When he is out of college, he goes to the Times and gets a job as a copyboy.

Meditations on the father generally revolve around the question of honor. What is right? How should one live one’s life? Almost a Family is inspiring because of how well Barney’s sons, guided by their vision of him, turn out. Again and again Bob puts himself between his younger brother and the problems created by his mother’s drinking. When the situation becomes dire Bob tells the dean of Andover he must leave school to take care of his family (the dean dissuades him). Love between the brothers runs through the book and even helps make its existence possible, when Bob shares with John his researches into Barney’s life. At the Times, that dread institution, John rises to become a reporter, then a foreign correspondent with all of Africa as his beat. Here the plot gets legs, as the author recounts adventures from Ghana to Nigeria to Mozambique. Transferred to Eastern Europe, he is present for the rise of the democracy movement in Poland, and his reporting of the historic events wins a Pulitzer Prize.

From boyhood the author understood journalism to be a noble profession, and his faith and works make it so. In a letter Barney wrote before going to the war, he called the press “an indispensable force in the achievement of democracy,” adding that its work “can’t all be easy.” Risking danger to cover the war is simply his duty, he says. Like the father, Darnton the son racks up many bylines in the paper, and as he does he begins to receive mementoes of the elder Darnton sent by other newspapermen and readers. Some of what he receives moves him—his father’s last notebook, with his final scrawls: “bombed by 2 eng. plane—500 yd. miss” and “Fahn shot 50 cal.” Other information puzzles him and suggests that the flat, heroic poster of his father in his mind is not completely accurate.

Advertisement

In earlier chapters the author has dropped hints of revelations to come. About three quarters of the way through the book he retires after forty years at the paper, and then aims his skills as a journalist at the obscure regions of his parents’ lives. It’s engrossing to watch what his digging reveals. He returns to one strange fact in particular: as his mother disclosed during her last illness, she and Barney were not married. Pressed for explanations, she remained vague. The author looks into the mystery in interviews with people who knew them, and learns about the unrestrained lives young creative people were leading in the city before the war.

Barney and Tootie had each been married when they met and began their affair. Their romantic lives, and those of their friends, had been rather sketchy, on the whole. Darnton quotes Barney’s remark, “It’s not wedding bells, but cheap hotels, that’s breaking up that ole gang o’ mine.” Darnton locates transcripts of the divorce proceedings that freed his parents from their spouses, and he includes the specifics. In this instance the hotels in question were the Hotel Astor and the Hotel Murray. From the names alone you can smell the ashtrays in the lobbies. The picture Darnton produces becomes interestingly more detailed, although the riddle of why they never married isn’t solved.

Darnton also goes to Adrian, Michigan, Barney’s hometown, and talks to relations there. Adrian is in the vicinity of Detroit and Ann Arbor, a beyond-the-beyond for Darnton, who feels little connection to it. An American rootlessness seems to underlie the good cheer of his cousins and uncles and aunts there; he gives a quick portrait of Barney’s brother Clifford, a man who used to disappear for years on end and ride the rails. Clifford showed up cold and road-weary one day at the Pennsylvania home of Robert, another brother, and asked for work. Robert made arrangements for a job, but the next morning Clifford was gone, along with Robert’s only overcoat. These and other glimpses of Barney’s past uncover folks as lonesome and transient and luckless as figures in a Hopper painting. One can’t help but wonder what Barney and his generation might have been without the war.

Another big question that vexes Darnton concerns Barney’s death. Shortly after it, officials confirmed that it had been caused by friendly fire (“that insidious oxymoron,” Darnton calls it). Barney and the troops waiting to land on the New Guinea beach had been bombed by an American B-25. Military higher-ups blamed the mistake on poor communications between air and ground forces in that mountainous jungle region, and they did not try to determine who the pilot was. They said the error was just something that happened in war.

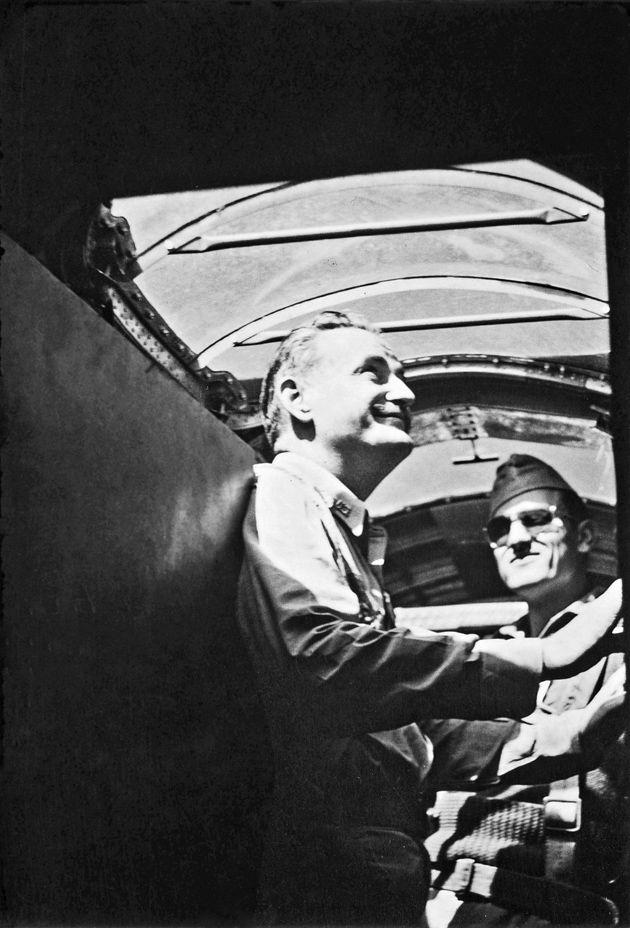

Darnton, however, burrows deeply into the incident. Eventually he finds the pilot’s name, David M. Conley; the name of the plane, Baby Blitz; and a photo of the plane and crew. Wanting to know if Conley, now dead, had ever expressed remorse, he even hires a private detective to find Conley’s son. The son tells Darnton that his father never spoke to him about the incident. In other researches Darnton also discovers that Barney, hit in the head by shrapnel, did not have his helmet on, and that impulsive machine gun fire from the landing ship may have provoked the attack.

As the facts accumulate, the effect is of a photo we zoom in on for greater detail. No new discovery significantly changes the original description of the incident by the military. But something about the cold randomness of it dissolves all notions of purpose or heroism. When Darnton reconsiders the incident again at the end of the book, he feels only “pure, white-hot anger,” and the reader can understand why.

After years of gathering information Darnton travels with his wife to the very place in New Guinea (now Papua New Guinea) where his father died. He wants to see the bay, the beach, the nearby village. Arrangements must be made in advance for them to land at the village, where a ceremony and gift-giving will take place. When Darnton steps onto the beach, men armed with spears make mock charges at him to open the formalities. In the hut where the people gather, long speeches ensue, and the sorrow that has brought him there mixes with curiosity, awkwardness, and strangeness. Among the villagers Darnton does meet one old man who remembers the bombing and the casualties lying on the beach. He recalls that he was on his way to school, heard the bombs, and ran back to look. He says he was too small to get close to the bodies. “I was appalled and saddened by what I saw,” he tells Darnton. “But what could I do? It had happened.”

Afterward, at another village, Darnton and his wife are led through a ceremony that requires them to undress and don local regalia. On that crucial morning back in 1942, Barney had neglected to put on his helmet; before this ceremony, his son forgets the insect repellent. As he stands on the sand in headdress and loincloth he is swarmed on by sand fleas. He ends up with more than four hundred bites, his own souvenir of sufferings gone by.

As a title, Almost a Family refers not just to the incomplete circle made up of the mother and two boys. It also has to do with honor, and honor’s mysteries and ambiguities. Barney went into danger for what he saw as his duty, Bob helped raise his younger brother, John became a reporter carrying out his father’s legacy and devoted himself to telling his story: all honorable guys. Meanwhile, journalism, the profession father and son lived by, rewarded its adepts haphazardly. It led Barney to a death that was, his son writes, “senseless, tragic.” It engaged the son happily and with much success for forty years. And in the form of the dread Times, the profession just would not give Tootie a break after Barney’s death when she was struggling.

Not many women worked for the Times then, and the dismissiveness of the handwritten comments made by her male bosses on her memos—more documents unearthed by the author—today sound unsparing to the point of cruelty. It’s poignant to learn that, as Darnton relates, his mother “remained starry-eyed about the paper despite her travails there,” and often praised its incorruptibility. Her faithfulness, even when she had been excluded from the club, is honor, too. At her death she had remained sober for fifteen years and was an active member of AA who helped others to sobriety. As she is wheeled off on the gurney for her last operation, Bob watches the back of her head and then sees her wave her hand “grandly in the air”—a final gesture of gallantry.

I have no demurral of any substance about this book, so if you’re a demurral-paragraph seeker, this will disappoint you. I do have one small complaint that I want to mention because it bugs me. Are books more carelessly edited than they used to be, or is it just my imagination? In general this book is not at all bad in that regard. However, I was discouraged to see that Knopf’s copy editors seem not to know the difference between “poured” and “pored” and “clamoring” and “clambering.” Also, on page 322, as the author is going to the village in Papua New Guinea, we are told that the local native people “eek out subsistence livelihoods.” Eek! Perhaps in future editions of this fine book the mistakes will disappear.

This Issue

May 12, 2011