1.

On August 5, 70 BC, at 1:30 in the afternoon, a remarkable criminal trial began in Rome. A young prosecutor named Marcus Tullius Cicero was accusing a senior Roman political official, Gaius Verres, of extortion and misrule during Verres’s tenure as governor of Sicily. “For three long years he so thoroughly despoiled and pillaged the province that its restoration to its previous state is out of the question,” Cicero proclaimed in his bold opening statement.

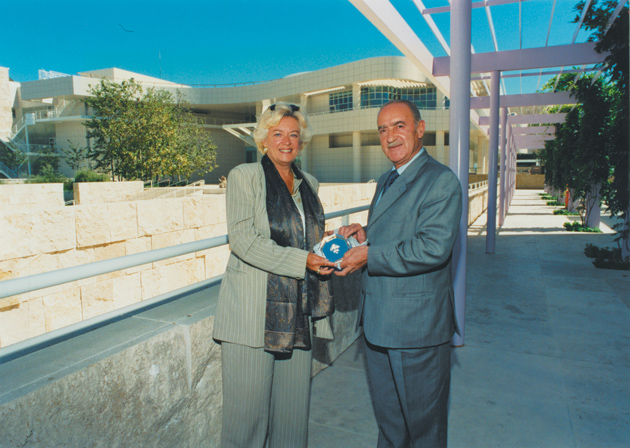

Italian Culture Ministry/AP Images

This late-fifth-century statue, thought by some to depict the Greek goddess Aphrodite, was purchased by the Getty Museum in 1988 from a London dealer for $18 million with no information about its origins. It was relinquished this year to a museum in Aidone, Sicily; Italian authorities believe it was looted from the nearby archaeological site of Morgantina.

Verres was well connected, and the case seemed to have long odds. Undeterred, Cicero suggested that his crimes were so numerous that it was hard to keep track of them: he sacked the treasury, manipulated the courts, stole grain from farmers, and connived with pirates; he locked up anyone he didn’t like (or the husbands of women he coveted) in the latomie, the fearsome subterranean rock prison near Syracuse, or simply crucified them.

Above all was Verres’s voracious appetite for art. “Ancient monuments given by wealthy monarchs to adorn the cities of Sicily…were ravaged and stripped bare, one and all, by this same governor,” Cicero continued.

Nor was it only statues and public monuments that he treated in this manner. Among the most sacred and revered Sicilian sanctuaries, there was not a single one which he failed to plunder; not one single god, if only Verres detected a good work of art or a valuable antique, did he leave in the possession of the Sicilians.

So overpowering was this opening statement, and the evidence used to support it, that Verres fled into exile and the trial was never completed. But that didn’t matter much to Cicero, who published the full legal arguments he had prepared anyway and was elected praetor two years later. “He never did anything on the same scale again,” Elizabeth Rawson writes in her classic biography of the orator. “Rome must have been dazzled.”

Ever since the Verrine Orations, the subject of plundered art has retained a special hold on the popular imagination, from Byron, who railed against Lord Elgin’s exploits in Athens (“Thy mouldering shrines removed/By British hands…”) down to Thomas Hoving, who engaged in some Elgin-like behavior before becoming a zealot of the anti-collecting cause.1 Beginning in the early twentieth century, if not earlier, it has also increasingly been a matter of law. Many countries have declared state ownership of artifacts found in (and on) their soil; more recently, some, including Italy and Greece, have shown a readiness to prosecute those who trade in them. Indeed, over the last few decades, the market for ancient art seems to have become ever more murky with the kind of dark dealings that Cicero, at his most prosecutorial, would have delighted in. Rarely, though, has the long shadow of the Verrines—the plunder and the rhetoric—been more present than in the unprecedented trial, also in Rome, of Marion True, former antiquities curator of the J. Paul Getty Museum in Los Angeles, which ended last year.

Along with two dealers, Robert Hecht and Giacomo Medici, True was charged with taking part in a decades-long pactum sceleris—a criminal conspiracy—to traffic in looted Greek and Roman art. As in the prosecution of Verres, the charges could draw on a huge body of evidence—in this instance, thousands of lurid Polaroid photo- graphs belonging to Medici, a Geneva- based Italian dealer, that showed freshly looted classical artworks subsequently bought by the Getty and other important museums. Again, with huge publicity, the case alleged that a statue of a Greek goddess had been brutally removed from its Sicilian sanctuary.

Unlike Cicero, Paolo Giorgio Ferri, the small, intense Roman prosecutor in the True case, is no great orator. Moreover, many of the objects he cited in the case had been acquired by the Getty and other museums twenty or even thirty years earlier—well beyond the statute of limitations for ordinary stolen art claims—and his theory of conspiracy raised numerous questions. Yet even without a verdict, the tenacious prosecutor managed to shock, cajole, and embarrass five of America’s leading museums into handing over more than one hundred works of art to the Italian government. Some of the museums have all but given up collecting antiquities; one, the Boston Museum of Fine Arts, agreed to have Italy review—and in effect have veto power over—any such acquisition it makes.

In achieving these improbable results, Ferri was assisted by Italy’s crack team of stolen-art cops, the Carabinieri TPC, or Cultural Heritage Protection Police, whose forensic diligence led to the discovery of the photographic archive of stolen works in a warehouse in Geneva’s Free Port; and by a group of officials in the Italian culture ministry who saw an opening to go after big US museums and ran with it. Critical, though, was the interest of American journalists. During the trial, Italian officials would leak information to journalists they liked, and made no bones about the extent to which they were waging their battle through the press. In 2006, Maurizio Fiorilli, an Italian lawyer who was closely involved in the prosecution, put it this way: “We have a newspaper in every [American] town where there is a big museum.”

Advertisement

But even taking this into account, the investigation of the Getty Museum by its hometown newspaper, the Los Angeles Times, stood out. Not only did the paper, in article upon article, put across the prosecution’s case against Marion True with particular force. It also brought out an extraordinary cache of evidence all its own, in the form of privileged legal files leaked from the office of the Getty’s in-house counsel. In early September 2005, for example, the newspaper disclosed that, in early 2001, a lawyer had advised Getty Trust President Barry Munitz not to share with Italian authorities True’s correspondence with the suspected dealers because the letters, which refer to museum purchases and potential acquisitions, were “troublesome.” This suggested to Ferri that, as he later told me in Rome, the Getty had “committed a disloyalty” by withholding material information about its antiquities acquisitions. As if that weren’t enough, a separate Los Angeles Times investigation was meanwhile exposing profligate personal use of Getty money by Munitz, revelations that ultimately led to his resignation.

Now, the dogged reporters who obtained the Getty files, Jason Felch and Ralph Frammolino, have published Chasing Aphrodite, an exhaustive account of their investigation. It is an important book, though not, perhaps, in the way they intend.

2.

A cynical portrait of the Getty Museum and its former curator, Chasing Aphrodite sets out to debunk the notion that art museums might have some legitimate reason for collecting art from the ancient past. “Museums have fueled the destruction of far more knowledge than they have preserved,” the authors state flatly in their prologue, a point they support with neither evidence nor argument. They then introduce their main theme:

Over four decades, the Getty chased many illicit masterpieces…. One of those acquisitions—the museum’s iconic seven-and-a-half-foot statue of Aphrodite, the Greek goddess of love—would become a totem for the beguiling beauty of ancient art.

The goddess held an allure so strong that a museum risked everything to own her; a nation rose up to demand her return; archaeologists, private investigators, and journalists scoured the globe for her origins; and a curator ruined herself trying to keep her.

With this Hollywood-trailer plotline, Felch and Frammolino aim to wrestle the vast body of internal memoranda, legal briefs, and museum correspondence that occupy the greater part of their nearly four-hundred-page book into a familiar story about money, art, and power. Although it was not originally part of the conspiracy investigation, the so-called Aphrodite, a high-classical Greek sculpture, became a sticking point in the Italian case. Acquired in 1988 for $18 million from the London dealer Robin Symes, the limestone-and-marble acrolith (literally, “having stone extremities”) had surfaced on the market with no information about where it had been found. Despite rumors about an illicit Sicilian provenance, four leading scholars attested to its signal importance and True promoted its acquisition.

During the trial, investigators hired by the Getty turned up photographs in the possession of the Swiss former policeman who prosecutors said had sold the statue to Symes, showing that it had been looted in recent decades and broken into pieces for transport. It was handed over to a small Sicilian museum in early 2011. Thus, in the authors’ account, “curatorial avarice” and the lure of a “voluptuous” fifth-century-BC deity turn Marion True, the curator of the “world’s richest museum,” into the “greatest sinner” in a field that was already rife with illicit activity and corruption.

Their approach has considerable expository appeal. It helps give thematic focus to an almost overwhelmingly detailed account of the Getty bureaucracy and allows readers to infer skullduggery in routine museum dealings—all of them somehow related to the goal of collecting looted antiquities. And with the Italian legal case against True, the authors also have a central character around whom to frame their story, a “heroine in a Greek tragedy.”

Felch and Frammolino scour True’s background and career for clues about what they suggest was a gradual descent into criminality. For example, though they seem not to have spoken with her (she declined to be interviewed for their book), they find much significance in the high tone of her voice, which could be a “sign of insincerity.” A series of part-time jobs she took in commercial art galleries while a doctoral student at Harvard meant that she was “struggling professionally.” And the failure of her first marriage—several years before she arrived at the Getty—is attributed to “her growing taste for extravagance.”

Advertisement

In her years as curator, they chart the “change in her personality” into “an imposing, matronly woman” who “cut people off with a hot glare or piercing remark and banished anyone who was judged guilty of disloyalty.” Meanwhile, she increasingly “exhibited the sense of entitlement that seemed to infect many at the Getty.” Above all there was the “small villa”—a house worth $400,000—she bought on the island of Pāros with money borrowed “from people who had sold tens of millions of dollars’ worth of a ntiquities to the Getty on her recommendation”—a conflict of interest that led to her dismissal from the museum in September 2005, just as her trial in Italy was about to start.2

Yet the particulars of Marion True’s downfall (and the Euripidean analogy) are not, at this point, particularly new; nor is the ambivalent outcome of her trial very helpful to the broad conclusions that the authors want to draw. Indeed, the trial’s denouement—it ended in October 2010, because the statute of limitations on the charges against her had expired—is relegated to just two sentences in the book’s epilogue, with the authors noting in passing that it leaves “unresolved the question of her guilt or innocence.” Also obscured are the outcomes of two further cases against True in Athens, both of which had been fueled by the Italian indictment, and which similarly ended with the court dropping all charges. (The authors mention only one of these cases, calling it an “uneventful conclusion.”)

The continued emphasis on True is puzzling, in view of the light the authors can cast on what did play out at the Getty and why the museum and the trust that runs it, with all its vast resources, got itself into such an entirely avoidable mess in the first place.

3.

It is hard to think of an institution more suited to Verres-like scrutiny than the Getty Museum. In the early 1980s, following the demise of its founder, the oil tycoon J. Paul Getty, the museum came into a billion-dollar inheritance; and like the oil curse, the money has come with a seemingly endless string of scandals, ranging from tax fraud to forgeries to allegations of sexual harassment and misuse of funds. (The museum is part of the Getty Trust, which also runs institutes devoted to art research and art conservation.) These incidents do not by any means tell the whole story of the Getty, and some of them have little to do with the Italian case. But they provide a colorful backdrop to Felch and Frammolino’s account. Indeed, though the fact was somewhat buried by the Los Angeles Times’s extensive coverage of the Rome trial, the Getty documents leaked to the reporters were not only, or even primarily, about Marion True.

Arguably the single most explosive revelation about the antiquities collection, for example, came in a set of cryptic notes taken in 1987 by former Getty Museum director John Walsh during a conversation with Harold Williams, the president of the Getty Trust:

HW: We are saying we won’t look into the provenance. We know it’s stolen. Symes a fence.

Both Walsh and Williams have insisted that these damning words were hypothetical in intent: they were considering how a new acquisition policy then being drafted would apply if a suspicious object came up for purchase. But regardless, the exchange made clear the degree to which the museum’s leadership was aware of, and sanguine about, the problems in the antiquities market. Worse, at the time of the conversation, the museum was indeed considering a major purchase from Symes—the very cult statue (the so-called Aphrodite) that later became so important in the True case. Were Walsh and Williams saying that they suspected it was looted? Why then did they approve its purchase?

Nor did the revelations end there. Before True became antiquities curator, her predecessor, Arthur Houghton, had relayed in writing some disturbing information to Deborah Gribbon, Walsh’s deputy director: Giacomo Medici, one of the dealers who would later be indicted along with True, had told Houghton that three works the museum had just acquired for $10.2 million—a statue of Apollo, a marble lekanis, or basin, and a rare fourth-century-BC sculptural group of two griffins attacking a doe—had all been pillaged in the mid-1970s from a site “not far from Taranto,” in southern Italy; the lekanis and griffins, he said, had been found in the same tomb.

Years later, when Gribbon herself had succeeded Walsh as director, this forgotten memo would be referred to as a “smoking gun” by Getty staff members; at the time of the True investigation, the memo was further corroborated by one of the most shocking Polaroids turned up by Italian police, a picture of the griffins, dirty and wrapped in Italian newspapers, in the trunk of a looter’s car. As Felch and Frammolino write, “The larger message was left unsaid. Problems in the antiquities department predated True and implicated her superiors, including the museum’s current director.”

It should come as no surprise that, as the directors of a young museum with a huge acquisitions budget, Walsh and Gribbon actively encouraged True’s cultivation of dealers and private collectors. Yet as Felch and Frammolino make clear, they were often less scrupulous than she was about Greek and Roman art of suspicious origin. In a series of chapters devoted to True, the authors portray her as a master of “duplicity” who dissembles to investigators, betrays colleagues, consorts with unsavory characters, and runs up a lavish expense account. But when it comes to concrete wrongdoing, the authors concede,

There was no evidence to suggest that True had been acting as a rogue curator. Indeed, documents unearthed in the internal review suggested that Gribbon, Walsh, and Williams had been fully aware that the museum was buying looted art and had approved all of the objects around which the Italians were building their case.

By the late 1990s, it was True who was criticizing the lax standards of the antiquities trade—and advocating the voluntary return of objects from the Getty for which clear evidence of illicit provenance had emerged—and Gribbon who was opposing her. “Gribbon began complaining to Getty CEO Barry Munitz [who had succeeded Williams in 1998] about True’s crusade against looted antiquities,” the authors write. “True had to be reined in.”

Why didn’t the museum make an effort to defend True vigorously in public? Was it worried that others might be implicated? Felch and Frammolino don’t directly answer this question. But they report that when members of the Getty’s board began to ask questions about the possible legal liability of the museum’s hierarchy, up to and including the board itself, the Getty’s in-house lawyers prepared a briefing paper that carefully downplayed the discovery of “‘troubling’ documents and ‘arresting’ Polaroids” in museum files; in a footnote the authors also add that, according to one person present, when trustees were orally briefed about True’s situation, “anything that seemed to point the finger at Gribbon” was omitted.

But there was something still more egregious about the readiness of Getty officials to sacrifice their curator and run for cover. In failing to recognize that the Italian case was really about the museum itself, Munitz, Gribbon, and the Getty’s board of trustees bungled numerous opportunities to resolve the case long before it ever went to trial.

4.

In the summer of 2002, while writing a magazine article about Italian efforts to crack down on the market for illegal antiquities,3 I spoke to a number of the officials involved in the sweeping investigation that would three years later result in Marion True’s indictment. At the time, their probe had not been made public, and they could not disclose that they were considering the unprecedented step of filing criminal charges against an American curator. But they did reveal they had persuasive evidence that dozens of works in American museums were looted from Italy. They also said that they had given the Getty a list of forty-eight such works and were prepared to make peace if the museum agreed to return some of them.

“We’re asking for a symbolic act of restitution,” Daniela Rizzo, a govern- ment archaeologist who worked closely with the Carabinieri and later became a star prosecution witness in the True trial, told me at the time. “It could be ten of these forty-eight objects, after which a new era of relations could begin.”4 Then she added a warning: “The museum is free to decide not to return anything, but at that point, it will have cut off its relations with Italy. We are ready to go to battle on this.”

In fact, as Getty documents leaked to the Los Angeles Times reveal, both Munitz and Gribbon had already been thoroughly briefed about the Italian investigation along these same lines. In their very first meeting with Ferri, in December 2000, Getty lawyers were told, as Felch and Frammolino summarize it, “Return the contested objects, and True will go free.” Less than two months later, in the same confidential January 2001 memorandum in which Munitz was advised not to share “troublesome” correspondence with the Italian prosecution, Richard Martin, an outside attorney for the Getty, informed him that General Roberto Conforti, the head of the Carabinieri’s art theft unit, was closely involved in the investigation, and that “we must be prepared to face the prospect of a public indictment against Dr. True in the relatively near future.” What the authors do not make clear is that Conforti’s main concern was, again, getting back antiquities. In the memo, which was copied to Gribbon, Martin cited the list of works that had been sent by the prosecutor (at that time it was only forty-two objects) and, in a passage they do not quote, stressed the importance of pursuing a restitution deal:

We believe General Conforti… has exerted pressure to proceed against Dr. True and the Getty. In the past, General Conforti has sought return of several items which…the Getty concluded were not appropriate to return. General Conforti has been frustrated by that position…. While the prosecutor has often said that his interest is in pursuing the network of dealers rather than Dr. True, we wonder whether there is anything which he and Conforti want from the Getty as part of an arrangement whereby they would agree to acknowledge that Dr. True’s involvement was, at worst, the result of negligence, rather than any intentional wrongdoing.

Prophetically, Martin also wrote:

I believe that we could successfully defend Dr. True in a trial in Italy…. We fully recognize, moreover, that trials and appeals in an Italian court, no matter how good the outcome for Dr. True, would be a disaster for her reputation and that of the Getty, and would prolong for years the public airing of these issues.

Despite such stark warnings, Gribbon decided to stonewall the Italians. A turning point came in a meeting in Rome in June 2002, when, according to Felch and Frammolino, General Conforti and other senior Italian officials presented Gribbon with much the same deal that the Carabinieri outlined to me that summer. “If the Getty was willing to give back several of the looted objects as a gesture of good faith, the Italians suggested, they would back down,” the authors write. “Otherwise, the Carabinieri official added, ‘this will go on for years and years, and in the end you’re going to give it back to us anyway.'” Astonishingly, Gribbon simply got up and walked out of the meeting.

More than two years later, on September 14, 2004, the Getty finally offered three objects back to Italy, but two of them already had prior grounds for restitution and the clearly looted sculpture group of the griffins was not among them. In the event, by this point Ferri had long since decided to pursue charges against True. A week after the Getty made that insulting offer, Gribbon handed in her resignation as director of the Getty, citing harassment by her boss, Barry Munitz—a feud that had done much to distract the museum from the investigation in Italy. As Felch and Frammolino report, she was quietly given a $3 million severance payment to drop her accusations and not speak to the press. (Accused of misuse of Getty funds, Munitz himself would resign in early 2006.)

5.

The full consequences of the Getty’s colossal missteps in the Marion True case have yet to be tabulated. But one conservative account might be found in the sheer cost of the case to the Getty itself. So many different lawyers worked on the trial and on the Getty’s own dispute with Italy and Greece that it is difficult to estimate how much was spent overall.

I recently reviewed tax filings by the Getty Trust showing that it paid $16 million for outside legal services between mid-2005 and mid-2007 alone—a period during which it had handed its Italian dealings to a team of lawyers from a high-end Los Angeles firm. (This does not include the $750,000 that, according to Felch and Frammolino, the Getty paid to a “crisis management” firm, also in Los Angeles, for “largely unheeded advice.”) A truer estimate, though, would also have to take account of the hundreds of millions dollars’ worth of art—far more than the Italians would have been contented with in 2002—that was finally turned over to Rome and Athens, leaving the Getty Villa a pallid shadow of its former self. Rarely have lawyers been paid so much to lose so much.

Yet the real damage of the case—apart from the ruinous and unjust consequences for True herself—may lie in its far-reaching effects on numerous other museums, which have rushed to relinquish numerous Greek, Roman, and Etruscan works from their own galleries to Italy, sometimes on what have appeared less than prudential grounds. Meanwhile, an Italian prosecutor has now initiated a criminal investigation of a curator at the Princeton University Museum of Art, on similar allegations of taking part, with an Italian dealer, in a conspiracy to traffic in looted antiquities. The case may yet resolve itself out of court (perhaps by sending more objects to Rome), but it suggests just how attractive the prosecutorial approach has become in some quarters of the Italian government.5

For its part, the Getty Trust has now hired James Cuno—the director of the Art Institute of Chicago and a staunch defender of collecting museums—as its new president. (The Getty Museum continues to search for a director, a position that has been open for over a year.) It will be interesting to see whether Cuno will succeed in persuading Italy to drop its continued efforts to get back the Getty Bronze, a second- or third-century-BC life-size bronze of a victorious youth, found in the Adriatic Sea in the early 1960s—a claim that some proponents of restitution see as far-fetched.

In recounting the Getty disaster with such relish, Chasing Aphrodite wants to attribute to it “an epochal change in the history of collecting art.” Indeed, the case has hastened a number of welcome changes at large (American) collecting museums, which have become far more vigilant about the origins of the art they acquire. It has also had a salutary effect on countries like Italy with large archaeological resources, which have begun to loosen restrictions on lending important material from their museums and storerooms to museums abroad. This is an especially desirable development (one that, as the authors note, True herself had advocated years earlier) and it is to be hoped that long-term loans, or even semipermanent loans, could allow well-endowed foreign museums to publish and display major works to very large audiences without having to resort to the acquisition of material of murky provenance from the art market.

Yet for all the documents they bring to light, there is an odd incongruity to the kind of prosecutorial certainty Felch and Frammolino bring to their story. As their own extensive footnotes reveal, events they want to see one way may be open to a quite different interpretation. Even now, scholars are trying to determine the identity of the cult statue after which the authors name their book (several think it is not Aphrodite); and archaeologists continue to seek the place where it was found. In the meantime, Italy can enjoy the same exquisite artworks of unknown origin that had previously graced American display cases: a victory less for archaeology, perhaps, than for the approach endorsed by collecting museums of showing beautiful objects that, even without knowledge of their discovery, may bring alive the ancient world to the modern public.

This Issue

June 23, 2011

Death and Drugs in Colombia

After the Flood

-

1

For the influence of the Verrines on modern thought about the ownership of art, see Margaret M. Miles, Art as Plunder: The Ancient Origins of Debate About Cultural Property (Cambridge University Press, 2008). ↩

-

2

Felch and Frammolino’s account of Marion True’s vacation house in Paros is puzzling. Citing a nephew of the late Christo Michaelides—the partner of London dealer Robin Symes, who frequently sold works to the Getty—they repeatedly assert as fact that True originally bought the $400,000 house with a “loan from Christo Michaelides.” They then write that True repaid this loan with a second loan from the collectors Lawrence and Barbara Fleischman, adding, “Many years later, it was unclear whether she actually made those [loan] payments. The Getty’s lawyers could find no proof that she had.”

This story is inaccurate. As they elsewhere acknowledge, the first loan was a four-year loan from Dimitrios Peppas, a Greek lawyer who arranged financing for shipping companies and who was recommended to True by Michaelides. The authors provide no documentary or other corroborating evidence that Peppas’s money came from Michaelides, which True has categorically denied, nor do they make clear that the story of the loan from Michaelides—or from Symes, according to the original rumor—surfaced after Michaelides’ death, at a time when his nephew was pursuing a legal fight against Symes over the Michaelides estate. Unless there is concrete evidence to the contrary, it seems unlikely that Michaelides—who the authors suggest was a personal friend of True’s—would have charged her the steep rate of 18 percent interest carried by the Peppas loan (a figure that the authors fail to mention).

Regarding the Fleischman loan—a thirty-year loan that in December 1998 was set at the prevailing interest rate of 8.25 percent—in February 2006, True’s lawyer sent a statement to Luis Li, a lawyer hired by the Getty to work on the antiquities case, affirming that True’s Bank of America accounts had been reviewed for the preceding seven years and that “the records show that…from January 1999 through January 2006 loan payments exceeded $162,000.00 and were generally consistent with the payment schedule in the loan documentation.”

Taking a loan from collectors who had sold works to the Getty was a serious lapse of judgment on True’s part, but the facts of the house financing do not bear out the authors’ claims. ↩ -

3

See “Looted Antiquities?” ARTnews, October 2002. ↩

-

4

In 2002, the Carabinieri told me there was a list of forty-eight objects in the Getty they believed had been acquired in violation of Italian law. Of these, however, there were forty-two that Ferri, the prosecutor, had officially listed as part of his investigation in the fall of 2000, and that were hence mentioned by the lawyer Martin in his January 2001 memo to Munitz. Subsequent lists grew to fifty-two objects (including both the Aphrodite and the Getty Bronze). In a 2007 restitution agreement, the Getty agreed to return forty works, including the Aphrodite. ↩

-

5

See my report, “Italy Focuses on a Princeton Curator in an Antiquities Investigation,” The New York Times, June 2, 2010. It is worth noting that the investigation once again mentions objects at a number of different American museums. ↩