1.

Is there a decent way to commemorate war? May and November holidays, parades and monuments, placing wreaths, playing Taps? At Gettysburg, a few months after some 50,000 men and boys had been killed or wounded there, President Lincoln spoke of “our poor power to add or detract” from their heroism. One suspects he knew we would always do better at the latter than the former.

David Blight has long been preoccupied with how Americans have remembered and misremembered the cataclysm that took place between 1861 and 1865. His Race and Reunion: The Civil War in American Memory (2001) was a valuable book about how civic leaders, historians, and writers of the early twentieth century erased what Lincoln had called “the cause of the war”—namely, slavery—from the national consciousness. At the fiftieth anniversary of the Battle of Gettysburg, Blight wrote, “the ghost of slavery” was “exorcised” by a “Blue-Gray fraternalism” that featured handshakes between former enemies (staged for photographers) over the same stone walls across which they had tried to kill each other with bullets and bayonets.

Veterans from both sides were invited, but there is no evidence that a single survivor from the 200,000 black men who had enlisted in the Union army showed up. Black workers delivered supplies and cleaned the latrines. President Woodrow Wilson spoke of the “wholesome and healing” half-century of peace, and said it would be an “impertinence to discourse on how the battle went, or how it ended,” much less “what it signified.” It was as if the Civil War had been a schoolyard quarrel that turned into a brawl—and no one could quite remember, or wanted to be reminded, why.

In his new book, American Oracle: The Civil War in the Civil Rights Era, Blight returns to the question of Civil War remembrance. This time he focuses on the nation one hundred years later, and approaches the subject not by surveying cemetery ceremonies, political speeches, and newspaper editorials, but through four authors—Robert Penn Warren, Bruce Catton, Edmund Wilson, and James Baldwin—whose writings on the legacy of the war reached a large national audience at the time of the Civil War centennial.

The National Civil War Centennial Commission, appointed by Congress and President Eisenhower in 1957, was trying to resume—more or less where the fiftieth anniversary had left it—“the consensual evasion” of what the war had been about. The commission included serious historians (Bell Irvin Wiley, Allan Nevins), but it was cochaired by the great-grandson of General Ulysses S. Grant, whom Blight describes as a “staunchly conservative superpatriot and racist,” and Karl Betts, a “media-savvy” businessman who wanted the observance to be mainly a matter, as it had been last time around, of “patriotic pageantry.” For the opening event in April 1961, thousands converged on Charleston, South Carolina, to commemorate—or celebrate—the firing on Fort Sumter as if it had been the pistol shot at the start of a horse race. The main hotel refused to admit blacks. A few months later, in northern Virginia, some 70,000 people paid $4 each (not a trivial ticket price then) for a bleacher seat from which to watch a reenactment of the First Battle of Bull Run—an especially satisfying spectacle for those whom Blight calls “professional neo-Confederates,” who came out to see Johnny Reb beat up Billy Yank once again.

But this was a different America from Woodrow Wilson’s America. Demonstrations, as well as violence aimed at the demonstrators, marked a new stage in the struggle to make desegregation a social fact rather than, as it had been since the US Supreme Court decision in Brown v. Board of Education (1954), a legal fiction. The Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) was organizing Freedom Rides in an effort to build public support for a more recent Supreme Court ruling in the case of Boynton v. Virginia (1960) outlawing segregation on interstate bus routes. Amid these contentions, Northern newspapers “had a field day pillorying” the Centennial Commission for its banality and backwardness—until, in the fall of 1961, President Kennedy replaced Betts as chairman with Nevins, whose allegiance was evident in the title of his multivolume history Ordeal of the Union (1947–1971).

Fifty years earlier, with Reconstruction abandoned and Jim Crow established, the war had been construed, in scholarly as well as popular accounts, as a constitutional dispute in which the main issues—state sovereignty versus federal authority; the controlling legitimacy of elections—were settled by the victory of the North. And by the middle years of the twentieth century, as Blight puts it, “both sides had developed comfortable havens of self-righteousness” about the terms of that settlement—one side harboring nostalgia for a fanciful version of Dixie defeated but unbowed; the other taking pride in the redemption of the Union as a nation of universal liberty.

Advertisement

The burden of Blight’s new book is that both views were evasions of the unpalatable truth that the war had left unresolved the fate of former slaves who emerged from it free in name but far short of freedom in fact. In May 1962, Martin Luther King Jr., in a letter to Kennedy that anticipated the great speech he was to deliver fifteen months later on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial, made the irrefutable point:

The struggle for freedom, Mr. President, of which the Civil War was but a bloody chapter, continues throughout our land today. The courage and heroism of Negro citizens at Montgomery, Little Rock, New Orleans, Prince Edward County, and Jackson, Mississippi is only a further effort to affirm the democratic heritage so painfully won, in part, upon the grassy battlefields of Antietam, Lookout Mountain, and Gettysburg.

“Won, in part” was the key phrase. With respect to racial justice, the Civil War was not over. It was awaiting completion.

2.

The four writers whom Blight brings forward as witnesses to this struggle had, initially, discrepant inclinations toward it.

Born in southern Kentucky in 1905, Robert Penn Warren delighted in war stories he heard from his maternal grandfather, who had fought for the Confederacy at Shiloh, participated in the slaughter of black Union troops at Fort Pillow (Grandpa Penn was reticent on this topic), and taught his grandson that the only good things to come along since the end of the war were “window screens and painless dentistry.” As a young man under the influence of the Southern “Fugitives” (John Crowe Ransom and Donald Davidson were among his mentors), Warren wrote that “the Southern negro” was, and should remain, “a creature of the small town and farm,” content to “sit beneath his own vine and fig tree.”

Warren came to repudiate such nonsense and, from what Blight nicely calls his “border-state angle of vision,” struggled to reconcile his sympathy for men like his grandfather, imprisoned in pardonable loyalty to place and comrades, with his disgust at the retrospective glorification of their cause by those who, from the “safety of mob anonymity,” howled “vituperation at a little Negro girl being conducted into a school building.” In Warren’s novel Wilderness (1961), about a German-Jewish idealist who joins the American war on behalf of “Freiheit” (freedom) only to discover brutality, racist fury, and heroism on both sides, and in The Legacy of the Civil War, also published in 1961, he tried, as Blight puts it, “to make the enthusiast think and the partisan to feel something about the other side.”

What Warren wanted his readers to think and feel was what he variously called “tragedy” or “fate” or simply “history”—the chaos of motives encompassing shame and pride and love and hate, forces that drove men “more and more vindictively and desperately until the powers of reason were twisted…and virtues perverted.” To Warren, the Civil War was a “crime of monstrous inhumanity, into which almost innocently men stumbled.” For rendering it as such, his reward was to be “hammered from the right and from the left” by hectoring devotees of the Lost Cause on the one hand and of the Stars and Stripes on the other.

Warren’s contemporary Bruce Catton was born in northern Michigan in 1899. As a boy, he marched each spring on Memorial Day (still known then as Decoration Day) behind Union veterans who, when the parade reached the town cemetery, strewed lilacs on the graves of their fallen comrades. Catton served his literary apprenticeship as a reporter and columnist for several urban newspapers and, later, as a member of the War Production Board, on behalf of which he produced press releases promoting FDR’s policy of preparedness—which meant, in practice, the production of military materiel in anticipation of war. Catton’s first book, about the US war machine, published in 1948, bore a title that was meant to be celebratory but today is likely to sound damning: The War Lords of Washington.

In what is perhaps Blight’s most interesting chapter, Catton emerges as a figure hard for us to fathom: a sort of literary Norman Rockwell, middle-brow in temperament, a virtuoso at his craft, and—hardly imaginable today—a left-leaning patriot with a huge public following. Beginning in the early 1950s with Mr. Lincoln’s Army (1951) and A Stillness at Appomattox (1953), and running through Gettysburg: The Final Fury (1974), Catton produced narrative histories that told—or, as some of his rivals believed, sold—“the collective story that those Union veterans in his hometown had symbolized.” It was his purpose to convey what Lincoln biographer Benjamin Thomas called the “heart-throb” of the Union army—to give to the victors in blue something of the romance and aura of valor and glamour that attached to the losers in gray.

Advertisement

Yet Catton had, as Blight says, the “uncanny ability to plant his flag in the North while writing about the war as a grand, national experience in the ultimate spirit of reconciliation.” (Alfred Knopf is said to have called him “the last survivor of both sides.”) His “soft sentences,” Blight remarks, “allowed both sides among his readers to feel a sense of ownership in the outcome,” and Blight faults him for his apparent ignorance of the experience of African-Americans before, during, and after the fighting—though he notes that Catton “forthrightly” acknowledged that true and full emancipation remained, in Catton’s words, the “profound…unfinished business” of the war.

In a sensitive account of Catton’s later years (he died in 1978), Blight shows him reflecting back on the limits of his own achievement, asking himself if he had exploited the public appetite for an elevating myth that would obscure the sordid reality of the killing fields—wondering whether he had indulged his readers, and himself, by telling a story of vast human suffering with gusto and something too much like joy.

When Blight turns to Edmund Wilson, born in New Jersey in 1895, educated at a Pennsylvania prep school and at Princeton, we come to a writer for whom Civil War reminiscence was not a significant part of his childhood, though he was encouraged by his father—a Republican lawyer with a taste for writings on self-improvement—to revere Abraham Lincoln as a paragon of American virtue. Nevertheless—or perhaps the better word is therefore—Wilson’s extraordinary work, Patriotic Gore, begun as a series of New Yorker articles in the 1950s and published as a book in 1962, gives evidence of what Blight calls “a soft spot for secessionists and Confederate antistatism.”

There is an element of truth in this judgment, but not in the sense that Wilson wrote with affection for the Lost Cause. He hated war, and had no patience for those who justified it on either side. Since, as the phrase goes, “history is written by the winners,” he had a special antipathy toward their story of national redemption. His was a contrarian brilliance, aggressively unsentimental, impatient with all pieties—aesthetic, political, personal. His experience in hospital service during World War I—when his job, Blight writes, was “caring for soldiers gone mad, and lifting corpses onto stretchers,” then “burying the cold bodies of the unlucky”—had made him allergic to any and every battle cry. Of World War II, he said that “bomb for bomb, we did worse than the Nazis.”

When he came to write of the Civil War—which turned out to be, in the scale of its carnage, a dress rehearsal for what lay ahead in the next century—it was with suspicion of high-mindedness on both sides. But he had a special animus for the innovators of “total war”—Grant with his technique of siege, Sherman with his strategy of mass destruction—though he credited both men, particularly Grant, with being estimable writers.

Patriotic Gore includes a long and appreciative chapter about Alexander Stephens, former vice-president of the Confederacy, who was imprisoned after the war in a fort near Boston, where he worked on a vast diary that remained unpublished until the twentieth century. Stephens was a states-rights ideologue and resolute racist, and Blight asserts that Wilson had a “rather nostalgic companionship” with him. But this phrase is off the point—which Wilson himself drives home in one of those marvelous passages that lift his book to the level of literature:

There is in most of us an unreconstructed Southerner who will not accept domination as well as a benevolent despot who wants to mold others for their own good, to assemble them in such a way as to produce a comprehensive unit which will satisfy our own ambition by realizing some vision of our own; and the conflict between these two tendencies—which on a larger scale gave rise to the Civil War—may also break the harmony of families and cause a fissure in the individual.

Patriotic Gore, Blight insists, would have been a richer and deeper book if Wilson had taken a greater interest in the experience of black Americans, whose collective destiny was at stake in the war. In this respect, he lagged behind the spirit of the times—at least to the degree that he might have recovered the experience of black Americans through works such as the antebellum slave narratives that were coming to light through the scholarship of some of his contemporaries. That Wilson, like most critics of his generation, failed to seek out such writings with anything like the zeal with which he mined the works of relatively inconsequential white authors is certainly true. Yet Blight concedes that “Patriotic Gore should ultimately be judged” not for what it lacks but “for what is in it.” What was in it was of such amplitude that we have yet to take its full measure.

The final figure in Blight’s quartet, James Baldwin, was both the farthest from and closest to the war. Much younger than Warren, Catton, or Wilson, he was born in 1924 to parents who had left the South and settled in Harlem. He felt no connection to the war through family lore. But he felt it in the fact of his blackness—as when, as a book-hungry teenager, he ventured down from his home on 131st Street to the 42nd Street branch of the New York Public Library, where he was told by a street-corner cop that niggers should get themselves back uptown where they belonged.

Blight captures the dividedness in Baldwin that was both profoundly debilitating and immensely liberating. It expressed itself in his love and hate of the storefront church where he first learned that words could convert shame into rage as his stepfather preached militance mixed with consolation; it expressed itself in his ambivalence toward his patron Richard Wright, whom he revered for voicing black anger and whom he denounced for the limitations of that voice. Baldwin led a frantic life of perpetual motion—between Harlem and Greenwich Village; among multiple white and black lovers, heterosexual and homosexual; between sobriety and drunkenness; between self-exile in the relative anonymity of Istanbul or Paris and bouts of celebrity back “home.”

Out of this taxing rhythm he developed an exquisite sense of the contradictions at the heart of life, and of American life in particular. “The war of an artist with his society is a lover’s war,” he wrote. Although he produced distinguished fiction and criticism, he found his best genre, in the late 1950s and 1960s, in the reflective essay as a vehicle for articulating ambivalence toward the nation he knew as cruel and self-deceiving but that he also knew was trying, in some halting way, to come to terms with itself through the Civil War centennial.

Baldwin wrote about the “ninety years of quasi-freedom” that were misrepresented as “emancipation.” He wrote of the need to “free ourselves of the myth of America,” where “words are mostly used to cover the sleeper, not to wake him up.” As an essayist—and, increasingly, as a public figure in demand for the prestige of his proximity—he threw himself into the business of waking the nation.

Traveling through the South, Baldwin witnessed the public awakening—fitful, fearful, reluctant—to the fact that America is not two separate white and black nations, but one mixed-race nation in spite of itself. He described

girls the color of honey, men nearly the color of chalk, hair like silk, hair like cotton, hair like wire, eyes blue, gray, green, hazel, black, like the gypsy’s, brown like the Arab’s, narrow nostrils, thin, wide lips, thin lips, every conceivable variation

—all proving that “the prohibition…of the social mingling revealed the extent of the sexual amalgamation.”

He excoriated America for having “spent a hundred years avoiding the question of the place of the black man in it”; but he also asserted, immediately after the 1963 rally at the Lincoln Memorial, that it was blacks who had “the most faith in this country.” Like King, he believed that this faith was ultimately not misplaced.

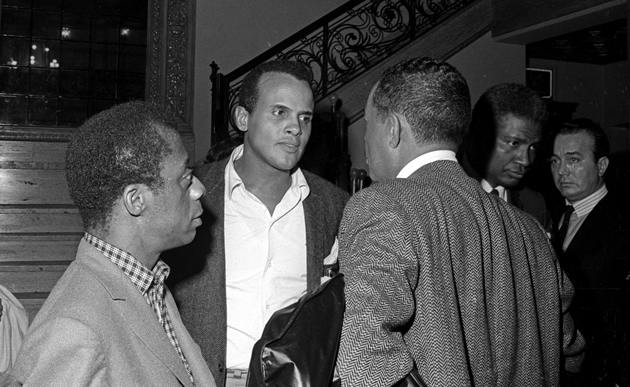

Blight concludes his chapter on Baldwin with a glance at a remarkable piece he wrote (published in Ebony in August 1965) about the march that had taken place that spring from Selma to Montgomery, when 25,000 people came to the old Confederate capital to protest police and mob violence. Confederate flags flew in mockery from the balconies and were stitched into the jackets of National Guard troopers who had been ordered to protect the marchers. White secretaries leaned from the office windows jeering with thumbs down—until they recognized that “beautiful cat,” as Baldwin called Harry Belafonte, among those who were marching. “When those girls saw” him, Baldwin wrote,

a collision occurred in them so visible as to be at once hilarious and unutterably sad. At one moment, the thumbs were down, they were barricaded within their skins, at the next moment, those down-turned thumbs flew to their mouths…their faces changed, and exactly like bobby-soxers, they oohed and aahed and moaned. God knows what was happening in the minds and hearts of those girls. Perhaps they would like to be free.

In some incipient and inchoate way, in those years of the Civil War centennial, America began to recognize itself as what Baldwin called the “most desperately schizophrenic of republics.”

3.

David Blight has written a searching and suggestive book. At the end of it, he leaves us with the not-quite-stated question of where we stand today with respect to what Baldwin called the “reflexes and fears and taboos and shibboleths” that have often been our “substitutes for memory.”

It is hard to say. We are just entering the second year of the Civil War sesquicentennial. Many strong books about the coming, conduct, and consequences of the war have already appeared,* and many more will doubtless follow before we reach the observance, in April 2015, of the surrender at Appomattox. America’s newspaper of record, The New York Times, is running a regular series in its online edition called “Disunion,” in which writers take us, often in efficiently vivid prose, back to long-ago events with the aim of making them feel current and fresh.

But there seems a strange muteness—is it exhaustion? confusion?—about how best to remember the Civil War so that it might connect in a vital way with contemporary experience. Pageantry, parades, and the like seem to have had their day—and a good thing too. No one should miss the triumphalism and lamentation that were once the competing currencies of Civil War commemoration. No one should wish to return to the strife and bitterness out of which a deeper understanding was forged in the 1960s. But surely the future depends, at least in part, on something we do not seem quite to possess: a truly convincing story, containing both admonition and inspiration, about the central event of the American past.

This Issue

February 9, 2012

The Wrong Leonardo?

Václav Havel (1936–2011)

The Republican Nightmare

-

*

These include several books reviewed in these pages by James M. McPherson, July 14, 2011: Amanda Foreman, A World On Fire: Britain’s Crucial Role in the American Civil War (Random House, 2010); Gary W. Gallagher, The Union War (Harvard University Press, 2011); Adam Goodheart, 1861: The Civil War Awakening (Knopf, 2011); David Goldfield, America Aflame: How the Civil War Created a Nation (Bloomsbury, 2011); and George C. Rable, God’s Almost Chosen Peoples: A Religious History of the American Civil War (University of North Carolina Press, 2010). Eric Foner’s important The Fiery Trial: Abraham Lincoln and American Slavery (Norton, 2010) was also reviewed by McPherson, The New York Review, November 25, 2010. ↩