Glimpsed on CNN at 5:45, the network crawl on caucus night: “Rap on Iowa: Too White, Too Evangelical.” The words were polemical but not untrue, and the thought might have occurred to someone before. But it had never been in the crawl before; there was a shortage of ideas at 5:00, and elections have become a yearlong entertainment. If, in the day of Lincoln and Douglas, they were outdoor dueling sermons with a picnic thrown in and freestyle challenges from the congregation, the paradigm seems to have shifted to American Idol or Survivor. An astonishing amount of the talk in the Iowa campaign was amateur talk; but, as on the reality shows, that is the point. The politicians are climbing the amusement ladder of January, March, and April. Only the prime time of the general election presumes that they be halfway informed, semicogent.

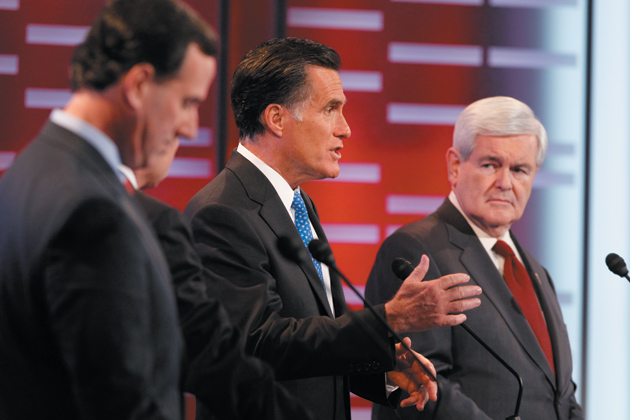

The new model may account for the number of candidates who participated in the twelve debates in Iowa, and the liberality of caprice shown by Iowa Republicans in shifting favorites. Michele Bachmann, Rick Perry, Herman Cain, and Newt Gingrich each enjoyed a swollen moment at the top. The evident aim of the “surge” for these candidates was to find the force that could destroy the Mitt Romney juggernaut: he was too predictable a figure, too much the “sound” choice, and too moderate for a party whose proudest epithet is “conservative.” Romney is seen as a man of the establishment, deep down; no sort of contrast to Obama, except in what he says today—but he talked differently yesterday.

A little over 122,000 participated in the caucus vote on January 3; together they made up 5.4 percent of voting-eligible persons in the state. Again, there is nothing wrong with the smallness of the sample if you take the reality TV model seriously. It might seem wrong for such a group to impose so large a tribulation for the public good. But in these winter and spring playoff rites of passage, an even tinier sample, say a town of 25,000, would do. In any case, how did people choose—what explained the binge of support for Rick Santorum over the last few days of the Iowa campaign? A young mother interviewed on MSNBC, asked why she supported him, said that she liked him because of, “oh, his concern with family values—and I have a family.”

Michele Bachmann, who had won the Ames Straw Poll in August, suffered more than anyone else from the sequential serenade that greeted the arrivals of Perry, Cain, and Gingrich. The first two were nibbled at by old memories of their opinions or their lives, and were seen to crumble as their endoskeletons were exposed. But Gingrich already had been exposed—hadn’t he fallen nearly as far as a public man can fall?—a stranded wreck that each new tide could only push a little farther up the beach. Yet as late as December 30, a Gallup Poll of Republicans nationwide found him even with Romney. As the outrage grew, at memories of his wealth, his recklessness, his wives and how he got them and left them, there could be no doubt anyway that Newt Gingrich was a source of wit in commentators.

They came, from all over the conservative world, to shower their insults on him: George Will, Michael Gerson, David Frum, and the smaller fry of pundits and bloggers at Commentary, and the National Review, and less-heard-of provenances. Among the recurrent themes: Gingrich has always been indifferent to truth; he is capable of saying absolutely anything; he is unstable and unreliable—the first of these words alluding to an inner and personal condition, the second to a manifest outward defect.

Many politicians of course suffer from an excess of energy and a convenient attitude toward truth, but the emerging consensus on Gingrich was: he can’t control his instability even for selfish purposes (let alone for the common good). “He is a human hand grenade,” wrote Peggy Noonan, “who walks around with his hand on the pin, saying, ‘Watch this!'” But it was Joe Scarborough, the morning talk-show host familiar with Gingrich as a fellow member of Congress in the 1990s, who found the simplest formulation: “If Newt Gingrich is the smartest guy in the room, leave that room.”

Politically, Gingrich’s weakest point was doubtless his having taken $1.6 million from Freddie Mac—for work (he said) as a historical consultant. That association could do real harm to a cherished Republican fable: Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac are alleged to be the root of the evil behind the financial collapse of 2007–2008. Many of the party’s leaders, and most of the prominent right-wing talkers who are in effect the party’s coaches, have placed the FMs in a completely different category from Goldman Sachs, AIG, Morgan Stanley, Bank of America, and other unregulated banks and financial firms. Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac are routinely denounced as a mortgage scam for welfare queens—an invention of Jimmy Carter and affirmative action that finally brought down the American economy. The renewable memory of Gingrich snuffling at that trough would rob the party of a magnetic issue before the general campaign got off its first antigovernment squibs and pinwheels.

Advertisement

A larger question set the Washington press corps to work. What had Newt been doing for the last fifteen years? What prospects remain, after all, for an ambitious freelance Republican after he is publicly disgraced? The answer was: plenty. Saving Lives & Saving Money (2003), Gingrich’s proposal for health care reform, in fact, shared many features of the Obama legislation—but it gave more emphasis to “predatory trial-lawyer behavior,” and took a singular interest in diabetes management. Two series of novels by Gingrich, about the War of Independence and the Civil War respectively, have moved further along in their trajectory. His most recent political seller, To Save America: Stopping Obama’s Secular-Socialist Machine (2011), turns out to be a religiose revision of To Renew America (1995), the bumptious manifesto that explained the rationale of the Contract with America of 1994. A more recent publication, Rediscovering God in America (2009), “Featuring the Photography of Callista Gingrich,” is a guide to D.C. heritage sites, from the Capitol and the White House to the National Archives to the war memorials and presidential monuments—an item meant to be sold in the gift shops on the Mall as a sort of earphone substitute and eventual souvenir.

Gingrich arrived in Congress in 1979 just as C-SPAN arrived; and in those days (the earliest memories of him, for many of us) he often stood alongside Trent Lott, in a chamber otherwise empty of every entity save the camera, and exchanged remarks on the public weal and scandals of mismanagement. Gingrich was always in command, and he was tireless. He could speak at sight on all subjects. It is a voice you can tune out, but tune back in with ease; it bobs along in bite-sized clauses of nine or ten words, the informality improved and not stiffened by a decent grammatical connective tissue. He has the air of a respected first-year college teacher, giving you some of his time, and he lets you stay on after office hours. Though Gingrich’s partisan animus was never in question, his penchant for covering all bets (knowledge-wise) with extreme statements on every side of a given question ensured against the tedium of moderation. He has the cocksureness, the insularity, and the continuous need of an audience of the born autodidact.

But Gingrich, as his supporters like to point out, is a licensed scholar. His MA thesis at Tulane on the effects of the Russian Revolution on French diplomacy (1968) ran 184 pages; his Ph.D. dissertation on postwar Belgian education policy in the Congo was nearly twice as long and relied on sources in French. The latter production comes to its first aimless but provocative paradox at the start of the third paragraph: “It would be just as misleading to speak in generalities of ‘white exploitation’ as it once was to talk about ‘native backwardness.’ We need to know what kind of exploitation, for what reasons, and at what price.” The pompous show of evenhandedness is nicely geared to approximate the thoughtless person’s idea of a thinking man.

If, as a party document, To Renew America left few bases uncovered, as a historical primer it left few origins unplumbed: “The Founding Fathers were all men of property who believed in honest money…. [They] assumed that the value of money was based on gold.” Gingrich acknowledged a profound debt to two inspirational sources: Arnold Toynbee’s ten-volume Study of History, which put him forever under the spell of civilizations, their rise and fall; and Isaac Asimov’s Foundation Trilogy, which, for Gingrich, reframed the study of civilization as science-fiction allegory. But what practical proposals were contained in this victory pamphlet? A flat tax. Term limits. English as the American language. An unimpeded right to carry guns (except for convicted felons).

It would be hard to exaggerate how far To Save America repeats the plot of the earlier election book—with Obama now, rather than Clinton, cast in the role of big-government intruder, and the bogey of the “secular-socialist machine” lifted from Fox News without much elaboration or embroidery. Gingrich himself plainly writes these books. It is like him to say that Obama “paid fealty to” his commitment to “non-ideological pragmatism.” (A ghostwriter would be less scientific and less chivalric.) The book, however, contains a new general innovation—“You should only get disability if you really deserve it”—and a new specific innovation: “Every teacher should report actual attendance electronically every hour.” But America also needs faster trains and better-functioning schools, and the secular-socialist machine won’t let us have them.

Advertisement

The main difference between the “renew” book and the “save” book is the overlay of piety. To Renew America was in fact a work of right-wing utilitarianism, its author a dispenser of nostrums who would have been at home in the world of Herbert Spencer, Thomas Carlyle, and Fitzjames Stephen. It disposed of God (cross-indexed “Creator”) in a single four-page section on “The Spiritual Dimension.” And the whole method and appeal of To Renew America lay in its trust in fast-track innovation on the corporate model. But now the big corporations have departed for cheaper labor and farther shores: “For the first time since the Civil War, we as Americans have to ask ourselves the most fundamental question possible: ‘Who are we?'”; and no longer can the answer be supplied by the felicific calculus or the laws of society understood as a biological organism.

To Save America is replete with the phraseology of “secular oppression”; its oppressors do not merely violate the spirit of the Founders, they are “holding the Constitution hostage.” The utilitarian dispensary seems truer to Gingrich’s nature than such simulated paranoia, and besides, this is a beast with laws of its own. “Who rides the tiger can never dismount”: but it must be added that the most perilous aspect of Gingrich’s temperament is doubtless the very thing that appeals most warmly to the people who are drawn to him. He loves the speed of the ride. It is a trait he shares with the revolutionists and imperialists who make his favorite study in the hours he can spare from public service.

Gingrich’s confrontation with his own life story produced some curious moments in 2011. How would he explain the recurrent “problem” of personal infidelity? In an interview with David Brody in March 2011, on the Christian Broadcasting Network, he confessed to a large-heartedness that might have strayed into exuberance: “There’s no question at times of my life, partially driven by how passionately I felt about this country, that I worked far too hard and things happened in my life that were not appropriate.” Gingrich had said something similar, but more raw and less equivocal, when interviewed by Gail Sheehy for a 1995 story in Vanity Fair: “I think you can write a psychological profile of me that says I found a way to immerse my insecurities in a cause large enough to justify whatever I wanted it to.” There, only the adolescent cover of “insecurities” is asked to palliate the length of his trespasses.

The puzzle is why such a person would want to remain in public view as a moralist. And yet, such is the wildness of moralism, many conservatives in an evangelical Christian state were ready to take him back. Was it worse than a minor flaw that Gingrich had become a serial dipper and sipper in the available modes of salvation, one of those Christians who have equal pleasure in sinning and repenting?

This would now be a major theme if he had beaten Romney in Iowa. But while his resurgence was on, Richard Land, president of the Ethics and Religious Liberty Commission of the Southern Baptist Convention, told an NPR interviewer on December 8 that the evangelical men in his two hundred focus groups were willing in Gingrich’s case to “let bygones be bygones.” Only the women wanted more: “They’re willing to forgive him, but they want him to ask for it, and they want to hear more regret.”

If anything united the Republicans besides their loathing for gun control, abortion, big government, and Obama, it was their avowal of hostility to Iran and support of anything Israel might do against it. The exception was Ron Paul, who in the twelfth debate went off script and off the reservation, with a statement grave enough to serve as a plank of a third-party platform. “To declare war on 1.2 billion Muslims and say all Muslims are the same, this is dangerous talk,” said Paul. “They don’t come here to kill us because we’re free and prosperous. Do they go to Switzerland and Sweden?… The CIA has explained it to us. It said they come here and want to do us harm because we’re bombing them.” He went further in a comment on Iran and the bomb quoted in The New York Times on December 31: “What are the odds of them using it? Probably zero. They just are not going to commit suicide. The Israelis have 300 of them.”

Paul owes his appeal in the libertarian wing of his party to the high proportion of candid statements about US war policy and the national security state that he has made over the past decade. In addressing such issues, he has no rival among Republicans, and, after the death of Robert Byrd and the defeat of Russ Feingold, none among Democrats of national stature. On issues of national security and war, he is the American politician who speaks to Americans as if they were grownups interested in their own condition, and as if the Constitution might have a direct bearing on our laws and conduct.

That his antistatism goes all the way to opposing disaster relief and economic planning, and calls for a return to the gold standard, assures that he will remain a minority candidate. Articles in a newsletter he sent out in the 1990s—tainted by racist and anti-Semitic slurs and formally disavowed by Paul since 2008—will also disqualify him with some voters who might otherwise be drawn to a representative who dared to defend WikiLeaks on the floor of Congress. But there is a peculiar gratitude people may feel for the bringer of inconvenient facts that are spoken without fear. Paul’s supporters are the most uncompromising in the party, and they are a growing minority: in 2008 he took 10 percent in Iowa, in 2012 it was 21 percent.

By contrast, the most belligerent Republican on Israel and Iran has turned out to be Santorum: he asserted, in a recorded conversation with a voter on November 21, that “all the people that live in the West Bank are Israelis, they’re not Palestinians. There is no ‘Palestinian.'” A few days earlier, Santorum had said about the threat of Iran: “A country that is developing a weapon of mass destruction to use it to destroy another country must be stopped in a preemptive strike.” And on Meet the Press on January 1 he affirmed his view in different words: Iranian leaders must open their facilities to inspection and begin to dismantle their advanced equipment, or the US will attack.

This statement comes at a moment of enormous tension—heightened by Israel’s warmest supporters in Congress. The Iran Threat Reductions Act, proposed by the Republican Ileana Ros-Lehtinen of Florida, passed in the House of Representatives on December 14 by a vote of 410–11. This crudely assertive and possibly unconstitutional bill would prohibit all contact between Iranian and American officials without fifteen days’ prior notice to Congress. Bill Clinton, in 1996, complained of the “scandalous electioneering” practiced by Benjamin Netanyahu from abroad.

Fifteen years later, ever since his visit to Congress in May, Benjamin Netanyahu has been working to intimidate the president and pull from Republican candidates and from Congress at large professions of loyalty to his project of bombing Iran to reduce its possible nuclear capability.

There has been a change, however, since 1996. Clinton’s anger was registered in private. But it was Thomas Friedman, the American opinion-maker most highly regarded in Israel, who wrote in a column of December 13 that Netanyahu’s standing ovation in Congress last May “was not for his politics. That ovation was bought and paid for by the Israel lobby.” And five days later, there occurred a remarkable exchange on Fareed Zakaria’s CNN program Global Public Square. The subject was how the Republicans try to outbid each other in submissive postures of unconditional loyalty to Israel; the immediate pretext was Gingrich’s having said on December 9 to an interviewer for the Jewish Channel (a cable station) that the Palestinians are an “invented” people. Zakaria and his guests then passed on to the broader subject of avowals of love for Israel and unquestioning support for Likud policies:

Zakaria: Michele Bachmann trumps them all by saying, “I went to a kibbutz when I was 18 years old.”

David Remnick: A socialist experiment, I might remind her. A socialist experiment. You know, as a Jewish American I find it disgusting. And I know what he’s going after. He’s going after—he’s going after a small slice of Jewish Americans who donate to political funds—to campaigns and also to Christian Evangelicals. It’s—the signaling is obvious. What they’re doing is obvious. But what they’re describing in terms of the, say, the Palestinian-Israeli conflict has no bearing on reality whatsoever. It’s ignorance combined with cynical politics and irrelevance. It’s really awful. It’s really awful.

Zakaria: Do you agree?

Peggy Noonan: Yes, I do.

Zakaria: Gillian?

Gillian Tett [of the Financial Times]: I do. And I think that actually given the current moves in Iran at the moment and what’s happening elsewhere in the region, that kind of rhetoric is likely to become more and more relevant going forward.

Zakaria: And then the other place where I noticed that there is some traction is Iran. There’s this feeling, again, I think somewhat unrealistically that we’re going to be tougher on Iran. We’re going to be, so that Gingrich says he wouldn’t bomb Iran, but he would effect regime change. Good luck, you know?

This was a breakthrough. Remnick’s comment is especially notable because it gives up the euphemism “Jewish voters” and refers frankly to Jewish donors. It is millions of dollars and not just a few thousand votes that the pandering Republicans are trawling for. Meanwhile, Israel itself has witnessed a development germane to the Republican pledges in Iowa of implicit support for any action by Israel. The majority of Israel’s intelligence establishment has actively argued against or publicly spoken to oppose the adventurist policy of Netanyahu and his description of Iran as an “existential threat.” These last words have been discountenanced by the present director of Mossad, Tamir Pardo, and, more sternly, by the retired director Meir Dagan, as well as by the former head of the Israeli Military Intelligence Directorate, Amos Yadlin, the former chief of staff of the Israeli Defense Forces, Gabi Ashkenazi, and the former Shin Bet chief Yuval Diskin. Opposition within Israel apparently succeeded in thwarting an initiative by Netanyahu to attack Iran in 2010. It remains to be seen whether it can do so again.

Probably none of the Republicans who clocked in at the Iowa debates to back aggressive US support of Israel against Iran was aware of this internal division—easily discoverable in recent stories in Haaretz and The Jerusalem Post. Such an uprising from the military and intelligence establishment itself, against an intended military action by an elected government, is exceedingly rare in the history of democracies. So we are at a strange crossroads. The right-wing coalition government of Israel is trying to secure support, with the help of an American party in an election year, for an act of war that it could not hope to accomplish unassisted; while an American opposition party complies with the demand of support by a foreign power, in an election year, to gain financial backing and popular leverage that it could not acquire unassisted.

By January 3, three weeks of ads by the Romney PAC Restore Our Future had cut down Gingrich from 26 percent to 13 percent. As long as there is a rostrum to lean on, he will go on talking, but his probable role has become that of a spoiler. What, then, to make of Rick Santorum, who fell just eight votes short of Romney in Iowa? The Fox talkers are a force to be reckoned with, in South Carolina likely more than in Iowa. Rush Limbaugh, who in 2008 did great damage by withholding support from John McCain until he picked Sarah Palin to run with, has shown unmitigated coldness toward Romney. He let out stray flickers of experimental sympathy for Perry and (in a more skeptical tone) for Gingrich, too, in early December, but Santorum’s strong showing on January 3 left him in a condition of explosive glee.

Gingrich, said Limbaugh to his listeners the morning after, was obviously enraged; he would seek revenge against Romney, and cut him up in debates and on the stump. “Newt’s not getting out. Newt’s in this to destroy Romney now.” For the coming South Carolina debate “he is loaded for bear.” With Bachmann retired and Perry as good as out, the conservative vote can rally behind Santorum. Temperamentally, Limbaugh is closer to Gingrich than are the mass of columnists and front-line party apologists who tried to bury him in December, and it is possible that Gingrich will indeed stay in, with just this function, out of a combination of spite and pride and a shade of sentimental regard for Rick Santorum—the weak halfback who just might score with a dirty block off-tackle.

Postscript: New Hampshire, in the last week before the primary, showed the vanity of all predictions about a party as veering as the Republicans are at the moment. Gingrich acted against Romney with an unbridled indelicacy. He said a private capital firm like Romney’s Bain—with a special line in takeover scams that minimize employees and maximize profits—failed in its moral duty when it denied compensation to the people it left jobless. Romney would “have to explain why would Bain have taken $180 million out of a company and then have it go bankrupt, and to what extent did they have some obligation to the workers? Remember, these were a lot of people who made that $180 million, it wasn’t just six rich guys at the top, and yet somehow they walked off from their fiduciary obligation to the people who had made the money for them.” With those words, Gingrich opened the dangerous subject of Romney’s fortune, and fleetingly placed himself to the left of President Obama, who has been careful to portray the financial collapse as a disaster without a villain.

But the staring fact about the New Hampshire vote was the continuing success of Ron Paul. He came in as the solid runner-up, 23 percent to Romney’s 39 percent, and got more votes than Santorum and Gingrich combined. His speech to his followers on primary night—which more nearly resembled a victory speech than Romney’s recitation from a teleprompter—was an enthusiastic cataract of words. “Freedom is popular,” Paul said, “don’t you know that?” And: “We’ve had enough of sending our kids and our money around the world to be the policemen of the world.” He took obvious pleasure in the fact that his door-to-door workers were young. And even the network commentators, wary to the point of avoidance of his campaign, have now begun to notice this.

The reason Paul commands a young following like no other Republican may be (as Chris Matthews pointed out) a certain idealism but also an innocence that has the force of a memory. His campaign returns a glimpse of what the GOP looked like sixty years ago, before it mixed its anti-state ideology with drop-in blocs of voters and advisers who want the state to serve their separate ends: converted Democrats from the South, the Christian right, the neoconservatives.

—January 12, 2012

This Issue

February 9, 2012

The Wrong Leonardo?

Václav Havel (1936–2011)