1.

Toward the end of Russell Banks’s new novel, Lost Memory of Skin, in what might seem a digression, someone called the Writer turns up and discusses the fate of Ernest Hemingway with the main character, the Kid, a twenty-two-year-old convicted felon living in part of the Everglades. The Writer says:

Hemingway blowing off his head with a shotgun in the kitchen while his wife is asleep upstairs. There’s a statement for you.

Yeah? What was he stating?

He spent his life killing animals with guns. Big dangerous animals like lions and water buffalo and rhinos. He wasn’t about to kill himself in bed with a bottle of vodka and a jar of sleeping pills or by taking a flying leap off the Golden Gate. Not a big dangerous animal like Ernest Hemingway.

Who was he stating it to? That he was a big dangerous animal.

History, naturally. Literary history.

This exchange pinpoints at least two subjects Banks often returns to: cruelty to animals and the implications for male writers of conceptions of manliness in the American literary tradition. When it comes to the anxiety of influence, American women writers seem to have an easy relation to their gentler and more urbane literary ancestresses; but men writing in America have to contend with the shade of Hemingway, and the longstanding tradition of manliness he tried to represent. They may reject that tradition but they can’t ignore it, though Henry James may have been trying to by making himself into an Englishman. Most of the ongoing mining of Ernest Hemingway’s character, sexuality, and personal history arises from our sense that he embodied the paradoxes and conflicts in masculinity as Americans have constructed it. Was he a bully or a baby, brave or cowardly, gay or straight, tough or weak? These are issues that American writers and scholars return to again and again.

These are also issues Banks’s main characters confront in Hemingway’s shadow, and not only in this new novel; it is also very dense with symbols freighted with social comment, as when the Writer says to the Kid, “So what about it, friend? Shall we take a little ride in my rental? It’s a Lincoln Town Car…,” and the Kid replies, “I dunno. I gotta charge my shackle.”

There seem to be two sides of Russell Banks: one is the respected writer of often grim realistic novels in the manner of Dreiser or Zola, movingly portraying lives in which things go from bad to worse, to the discredit of an America where many things are wrong. Some of his most admired works fall into this category, Affliction (1989) and Continental Drift (1985), for example. But there’s also the novelist of considerable audacity and originality who speaks, for instance, in the voice of a woman founding a chimpanzee rescue facility in Liberia (The Darling, 2004); or who imagines what life would be like in a small town after fourteen of its children die tragically in a school bus accident (The Sweet Hereafter, 1991); or whose main characters are a homeless pedophile and an obese professor (Lost Memory of Skin), and he makes us turn the pages with avid readerly pleasure.

By choosing to write about a convict living in a seedy Florida waterfront homeless camp—a small, inept youth entrapped before he could consummate his Internet date with someone he thought was a girl but who was really a policeman—and the obese academic called the Professor, Banks takes on a huge challenge: Can there be categories more despised than child abusers, hugely fat people, and, alas, probably professors? But he elevates his difficult subject to the level of admonitory fable and pathos in the manner of Charles Dickens in a high comic tone, while also showcasing his own palpable humanity.

2.

The novel begins by following a “fatherless white kid who graduated high school without ever passing a single test or turning in a single paper, a kid who could barely read or write or do math beyond the simplest level of arithmetic…and never had a girlfriend or a best friend….” In the homeless encampment, he sleeps in a tent, and his only real friend is Iggy, his pet iguana; after his time in prison, people he used to know, including his inadequate mother, have pretty much abandoned him. Yet he plays by the rules, earns money where he can, reports to his parole officer, recharges the anklet he will have to wear for ten years, and is considerate and helpful to the even more luckless other denizens of the camp.

The second main character, the Professor who comes into the Kid’s life, is another sort of outcast, a man whose immense corpulence and supposedly great intelligence have always made him unlike other people and somewhat repulsive to them. He’s married and has children, but nonetheless is locked into his solitude, a boy who didn’t fit in, college informer, adult double agent, estranged from his elderly parents—maybe someone whose compromised past comes back to kill him, maybe someone who will kill himself in despair.

Advertisement

The Professor and the Kid are larger-than-life characters, unlike Banks’s more characteristic lower-middle-class regular guys down on their luck, whose sufferings are often self-inflicted, from character flaws in turn arising from the effects of powerlessness and poverty. The Professor is a sociologist, ostensibly studying homeless felons. He is moved by the Kid’s plight, and offers him friendship as well as money and advice.

Over the course of the story we come to learn about the unjustness of the Kid’s felony conviction; far from being a sexual predator, he’s in fact a shy virgin, and we are made to feel the implications of poorly thought-through laws, the inflexible judicial system, failed educators, police brutality, harsh sentences, lives gratuitously ruined by prisons, and so on—subjects bound dependably to rouse our own indignation. Banks scarcely lacks targets of wrath, and he loses no chance to wring a tear from us at the Kid’s innocently perspicacious intuitions and acts of kind-hearted generosity. He saves a mangy dog and a parrot, uses his last dime to buy dog food, and tries to rescue people when they are dislodged by a storm surge—these are the claims on our sentimentality that invite the comparison with Dickens, with whom Banks shares the ability to produce scenes of nearly unbearable poignancy.

3.

It used to be, before reading habits changed, that young women entering college would have read basic classics—Treasure Island, Huckleberry Finn, Jane Eyre, Little Women—but young men would have read only the first two. Bookish girls unconsciously accepted early that the default narrative consciousness was male, and it didn’t bother them; they happily read books by both men and women, though sometimes with girlish reservations (but why did they have to kill the bear?).

Boys were not often encouraged to read books by female authors, and may actually have resisted it, or been prevented by fathers or custom. Maybe this is no longer the case, but I’m sure it remains true that men don’t read books by women nearly as often as women read books by men, even adjusting this observation for the fact that women read more in general, apparently, and men write more books. Not reading the Brontës, say, amounts to cultural deprivation for men, and this cultural deprivation, along with other masculinity issues like courage, sexual prowess, etc.—notions of manliness in our society that have been among Banks’s abiding preoccupations, or targets, rather—recurs more or less explicitly in his novels, as the characters think about their sons, like Bob Dubois, in Continental Drift, who “would have no choice but to try to be the same man his father had been with him,” or worry about what their brothers or male colleagues think of them, and thus are led into various forms of misery and error the closer they conform to false manly ideals.

The philosopher Martha C. Nussbaum, writing about patriotism, pointed out how much mischief, even downright evil, is done in the world because of “diseased norms of manliness.”* In her view, which is informed by the German philosopher Johann Gottfried Herder, these arise from primitive emotions of shame and disgust. Disgust stems from our unease with our mortal bodies, because they will “die and decay,” but it is often projected onto others, either the other sex or other ethnic groups. Most important, says Nussbaum, studies associate the feelings of disgust and shame with “aggression against the weak and against women,” something that seems an ingredient, if not at the root, of a lot of the political and religious ferment we see everywhere in humiliated societies, and is very much one of Banks’s concerns. He suggests in the remarkable and ambitious historical novel Cloudsplitter (1998), for instance, that John Brown’s humiliation in business was one wellspring of the violence of his opposition to slavery.

And shame, for men, in turn “focuses on the alleged shamefulness of the very fact of needing others,” hence the famous loners found in our literature and art, of whom, say, the Lone Ranger typifies the ideal, positive version: strong, generous, gallant, unattached. Rituals of manhood often involve periods of survival in solitude and some physical test—often killing an animal. The Kid in Lost Memory of Skin will find strength and renewal during his sojourn in the wilderness, here the solitude of the Everglades, where he dreams in the manner of Indian youths at their Outward Bound–like initiations, or, perhaps, Christ in the wilderness. His redemption will involve reentry into society, as he is changed by the dawning of a sense of self-worth.

Advertisement

Banks makes the point in a number of his novels that our notions of manhood are self-destructive, and that this is a serious problem in American society. We see the depraved face of the animal-killing ritual when the police slaughter Iggy for no reason. In The Darling, the woman narrator observes that “despite everything that had already happened, I’d still not imagined the discovery by men and boys of the pleasures of pointless destruction.” Unlike many male writers, Banks seems comfortable in the mind of a female narrator perhaps because he acknowledges the extent to which the opposite gender feels “other” and makes an effort to conquer the gap. “Men and women see each other differently,” says a character in The Sweet Hereafter, “we men have usually taken the physical measure of the women in our lives only with our eyes, and because we are secretly afraid of them, we tend to see women as having bodies that are at least as large as our own.” Yet “how small and delicate their bodies are in comparison to ours.” Elsewhere, “men and women seek the love of the Other so that the old, cracked and shabby self can be left behind.”

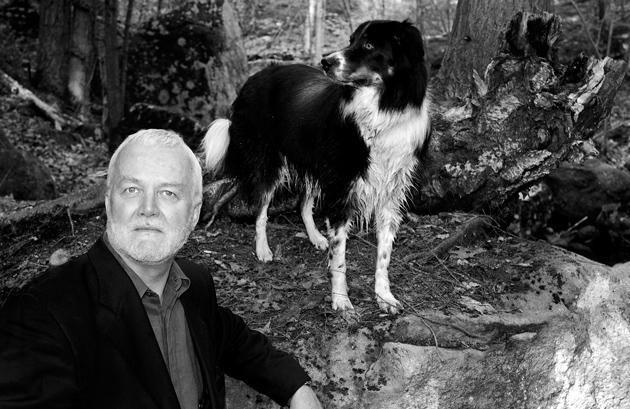

As readers, we have a relationship with the author of a work as well as with the characters and narrator; we are always somewhat aware of the concerns and personality of the writer himself behind the scenes. We have an idea of Tolstoy, say (strange, lordly, bearded), or of smart George Eliot, or of anyone you want to read all the books written by. If we set out to read any of Banks’s eighteen novels, we get a strong sense of the intrinsic humanity that infuses his works, think of him as something of a bleeding heart, with—a trickier quality to identify—a virtuous lack of egotism and a large capacity for empathy with women and other vulnerable beings, what Keats would have called “negative capability,” which allows him to shift shapes as he tries to get to the core of great subjects like cruelty and masculine swagger.

Like Dickens, Banks is a great storyteller. The Kid’s plight and our sense of his underlying innocence unfold from page to page as he and the Professor endure the trials and injustices society and nature have in store for them—police raids, storms, the reality of needing to get the next rent payment, the desperate situation of stray animals and homeless people, the tattered world of the poor. Our concern for the fate of the unlikely pair and involvement in their story are wonderfully gripping; all our senses of fairness and humanity are tweaked, even as we know how Banks is doing the tweaking. Oh, no, is he going to make the cops kill Iggy, the Kid’s pet since he was a boy, his only friend, living there with him in his tent, as the police raid the squalid encampment?

Banks’s preoccupations are not elusive, and moral ambiguity is not in his nature. Despite the powerful ironies his denouements often involve, we always know where the writer stands and how we ourselves are supposed to feel about the situations and characters in his stories. It’s the force of his righteous indignation that made the Civil War terrorist John Brown such a perfect subject for him in Cloudsplitter, where his chosen narrator, Owen Brown, one of Brown’s surviving sons, is made to express ambivalence about the family project to kill slave owners and try to foment a slave revolt—allowing Banks to examine the paradoxes involved in using terrorism and violence for good causes.

Because victim-heroes can’t be implausibly articulate, Banks often chooses to tell a story from the point of view of a narrator bystander—a relative, maybe a brother or son, like Owen Brown or, in Affliction, the brother of the central character, Wade Whitehouse, an out-of-control drunk who harms everyone connected with him as his life unwinds: he gets fired from his job as cop, loses his wife and his daughter’s love, and is driven to commit murder by the injustices that are heaped on him and that he brings on himself. This is the history of Bob Dubois, too, in Continental Drift.

In Lost Memory of Skin, Banks solves the problem of the Kid’s lack of education and experience by allowing his interior monologues sometimes to imperceptibly slide into the author’s, or by description so skillfully done that we never object that the Kid identifies a sophisticated list of Everglade birds without having ever read the bird guides of Roger Tory Peterson. The narrative slips in and out of the minds of each character, along with a third presence, the author, who delivers an occasional sermon or a moral gloss on the action, subtly elevating the diction to the level of the pulpit or textbook when there’s a point to be made or even a simple instruction to be given:

If you’ve never paddled a canoe before it can at first be surprisingly difficult—you have constantly to correct the tendency of the bow of the canoe to swing in the direction opposite your paddle. At first you may try correcting the tendency by alternately dipping your paddle into the water on one side….

And so on for a full page.

Banks has some fun letting the Kid express some politically incorrect views:

NPR—the Kid hates that network …with the puzzle-master Will Shortz setting little language-and-number mousetraps designed to make you feel stupid and that weird deep-throated guy who sings folk songs his grandparents liked and tells definitely not-funny stories about pie-eating Lutherans from Minnesota and some breathless woman interviewing writers and politicians you never heard of and of course constant news…told by people trying to sound like they’re English.

The Kid has a lot of such unimaginable apostasies, testimony to a kind of mental, if uninstructed, resilience reassuring to the reader who would otherwise be undone by the poignancy of his hopeless situation and the sweetness of his misunderstood and Christ-like nature—society’s victim outcast, cooperating with his persecutors.

There are a few other characters who drift in and out of what is essentially a road novel. One of them, Dolores Driscoll, appeared in The Sweet Hereafter—she was the driver of the school bus responsible for the accident that killed a town’s children. Now she’s washed up in a remote boat rental agency in the Everglades, here called the Great Panzacola Swamp. She also serves as a narrative consciousness from time to time:

She remembers how every year or two a scrawny pale boy several years short for his age and looking almost malnourished would show up on the first day of school…a new boy in town who couldn’t make eye contact with anyone…. They were born to lose, those little boys….

The passage is much longer, of overwhelming pessimism; she seems to articulate concerns that lie at the heart of much of Banks’s work. But the final passages of the novel are redemptive and heartening: “He’s not as sad and beaten down as he looks however. Heroes never are.” With so much wickedness and stupidity in the world, only the essential goodness of the Kid’s nature, and his resilience, given the harshness of the hand he was dealt, save the reader from despair. The Kid was one of those little boys, but small signs of his eventual rehabilitation con- sole us.

This Issue

March 8, 2012

Schools We Can Envy

Work, Not Sex, At Last

Why Not Frack?

-

*

“Toward a Globally Sensitive Patriotism,” Daedalus, Summer 2008. ↩